This article originally appeared in the May 2000 issue of SPIN.

Slipknot have a motto: People = Shit. It’s a straightforward enough sentiment, but sometimes Iowa’s most famous metal nonet like to reinforce the theory with visual aids.

“Shawn [Crahan, percussionist] decided to take a shit onstage in Virginia Beach last night,” drummer Joey Jordison says. “I’m the only one down with that, so he threw a turd at me. When I went to take a shower, I had this big shit smeared on my sock.” Jordison (a.k.a. #1), is loudly discussing feces as he and bandmates Crahan (a.k.a. #6), vocalist Corey Taylor (a.k.a. #8), and bassist Paul Gray (a.k.a. #2) stroll through the National Museum of Natural History in Washington. D.C., where they are scheduled to play a show tonight.

Not surprisingly, the guys are enthralled by the museum’s collection of animal skeletons, stuffed undersea specimens, and ugly, overgrown insects (“I just happen to be fascinated with the bug world,” Crahan says). Slipknot have built a brief but already noteworthy career as connoisseurs of the gross and grotesque.

Virtual unknowns from Des Moines before their second-stage stint on last year’s Ozzfest tour, Slipknot sold an impressive 15,000 copies of their self-titled debut on the indie label Roadrunner the first week after its June release. The album has since gone gold, despite a relative lack of mainstream radio and MTV support, as metal fans have slowly discovered the band’s squalling mix of machine-gun guitar missives, three-drummer tribal wallop, and otherworldly sample manipulation. Lyrically, Slipknot take aim at a litany of perceived betrayers, oppressors, and trash-talkers (“You ain’t shit, just a puddle on a bedspread,” Taylor rants on “No Life”). The overall spirit is righteous, cold indignation, although moments of well-wrought imagery and repulsively rich humor are woven into the apoplectic noise.

But it’s the band’s conceptual underpinnings that make them glitter in the thrash bin. First there are the onstage theatrics, which have included smashing a goat’s heart, heat-induced vomiting, and former welder Crahan partially severing a finger while showering the audience with sparks from an angle-grinder. “It’s not like we get out the goat heart every night,” Jordison says. “The music just brings it out of us sometimes.”

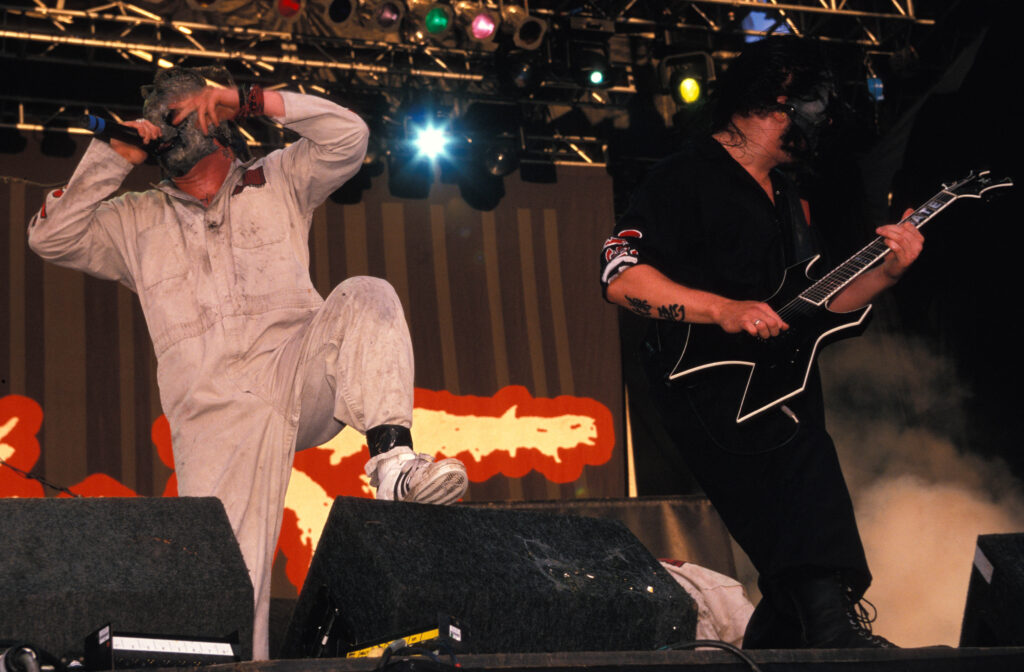

Most strikingly, though, there are the masks—grim rubber visages ranging from a leering pig face to a deranged clown to an exhumed Rasta corpse. The band say they wear them to put the focus on their music and not on their personalities, which is why they also sport matching prison-style coveralls and identify themselves by numbers instead of names. But it actually has the opposite effect: If the masks aren’t a surefire attention-grabber, then Crahan is the new Perry Como.

Marilyn Manson or Insane Clown Posse could have told them that disguises win prizes in the new rock sweepstakes, although dressing up didn’t exactly work for fellow costumed metallists Gwar in the early ’90s. Gwar leader Dave Brockie sees the recent public embrace of acts like Slipknot as a natural result of grunge’s anti-showmanship ethos. “For a while,” Brockie says, “the flavor was to look as dirty and grubby as possible. Then people got tired of that. Kiss put their makeup back on, and the floodgates burst open.”

Without their surreal headgear, the members of Slipknot look pretty normal. If there’s ever a sequel to the Flintstones movie, the bearish Crahan, 30 and a father of three, could be John Goodman’s stunt double. It’s even possible to believe terminal nice-guy Taylor when he cops to a Yahtzee addiction. The band’s habit of taking swings at one another (Crahan and the comparatively puny DJ Sid Wilson (a.k.a. #0) are frequent pugilistic opponents) is actually a sign of solidarity. “I don’t laugh with my best friends,” Taylor says, “but I get around this band, which is my family, and I fucking die.”

Slipknot formed in 1995 when Des Moines rock-scene vets Jordison, Gray, and Crahan would meet for late-night band strategy sessions at the gas station where Jordison worked the graveyard shift. With a self-released demo, Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat., under their belt, they propositioned Taylor while he doled out peep-booth tokens as a cashier at a downtown adult bookstore. “They were the baddest thing to come out of Des Moines,” Taylor says. “Sound-wise, musician-wise, intensity-wise, you couldn’t touch it. And I hated them for it.” Naturally, he joined up.

Of course, being the hottest band in Des Moines is a little like winning a wet-T-shirt contest at a National Association for the Blind convention. Recent A&R interest in the city—thanks to Slipknot’s success—notwithstanding, the band sprang from a breeding ground better known for its copious Jell-O consumption (the highest per capita in the nation) than its appetite for the musical arts. (The region’s largest nightclub, Super Toad, is also in a family-fun emporium that features a mechanical bull.) Taylor categorizes life in Des Moines as a “nonstop shit-eating fest. We had to make the loudest noise possible.”

Slipknot eventually attracted the attention of neo-hesher producer Ross Robinson (Korn, Deftones), who signed them to his Roadrunner-distributed I Am imprint and produced their debut. The tedium of the band’s hometown is not lost on Robinson. “The silence will either drive you crazy or drive you to express yourself,” he says. “With them, it’s a little bit of both.” Slipknot’s association with Robinson has bolstered the irksome-if-justifiable Korn comparisons that often come their way. “It’s like Ozzy said once,” Gray says. “Everyone’s a thief; no one’s completely original. It’s just the way you take all those things and produce something new.”

At least that sentiment is more profound than the one the headbanging godfather expressed when he first met Slipknot during Ozzfest. “I go to hug [Ozzy] with a Coke in my hand, and it’s like dump—right down the fucking madman’s back,” Jordison says. “He got pissed off, so you know what he did? He farted, and it stunk like a motherfucker.”

The performance this evening at D.C.’s 9:30 Club fails to yield any airborne turds, but it opens with an even greater horror: Gary Wright’s treacly 1975 chestnut “Dream Weaver” wafting over the P.A. By the second verse, teenage cries of “What the fuck is this shit?” fill the air. Two young fans wave lit matches in ironic arena-rock appreciation.

The choice of lead-in music is a nice counterpoint to the high-volume proceedings that follow. Bathed in strobe lights, Crahan, appearing far angrier than any man in a clown mask has a right to be, shakes his fists, slowly draws a drumstick across his throat in mock suicide, and manically humps his drum kit. Turntablist Wilson and percussionist Chris Fehn (a.k.a. #3) carry a beer keg onstage, douse it with an unidentifiable liquid, and light it on fire as the band launch into “Wait and Bleed.” Wilson climbs the speaker stacks and executes a spiraling dive into the crowd, which catches him. The chaos pauses when Taylor holds up a recent issue of Teen People.

“I was pissed off like a motherfucker when I saw this,” the singer barks, displaying a Calvin Klein ad featuring bare-chested Korn drummer David Silveria posing saucily. Taylor holds a match to the magazine and shouts, “People like that are destroying music!” The band kick into “Surfacing” and Taylor screams the chorus: “Fuck it all! / Fuck this world! / Fuck everything that you stand for!” as he stamps his boot-clad feet. After the show, Wilson thoughtfully hands set lists to lingering fans, drooling thick loogies onto the scraps. Backstage, the rancor over Silveria’s glamour-boy posturing continues as Slipknot shake off the excess adrenaline.

“I hope I get out of the business before that ever happens to me,” Crahan says. “We had hope [for Korn], but it’s sad, man. I’m disgusted.” Slipknot’s sole concession to fashion has been to purchase a backup set of coveralls. “The only thing we’ve ever wanted to do,” Taylor says, “is to make the most ruling music. And to kill everybody.”

Leave a comment