No one was going to be fooled by the disguise, if you could even call it a disguise — a plain, olive-green WWII-style helmet, with a blond, shoulder-length wig coming out from inside. But Eddie Vedder put it on anyway as we headed out from the backstage area of Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre in Orange County, California, on a warm October afternoon.

And no one was fooled. As the gate swung open, squeals started amongst several dozen young fans — female and male — who had gathered hoping for just a glimpse of someone, certainly of him. And here he was, walking out in their midst.

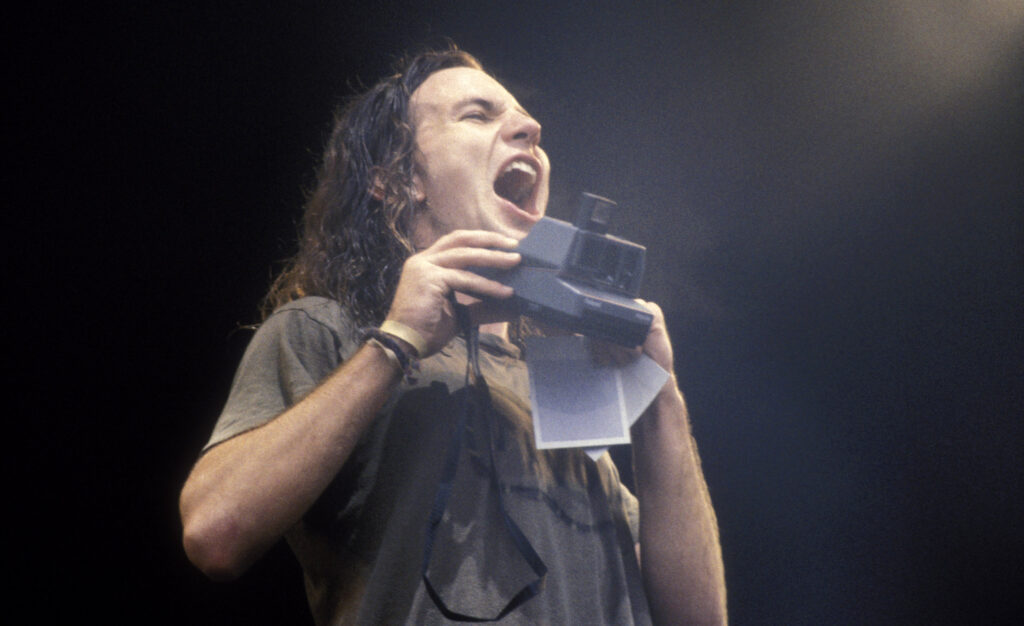

An hour ago he’d finished fronting Pearl Jam’s explosive set. It was the final day of Lollapalooza 1992, and Vedder was the man ofthe hour, the man of the tour, the man of the season. I’d been assigned by the Los Angeles Times to interview him there, where Pearl Jam in this second year of the multi-city traveling alt-rock festival joined a mainstage lineup topped by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, with Ministry, Ice Cube, Soundgarden, the Jesus and Mary Chain and Lush also on that bill. The inaugural ’91 Lolla was an experiment, headlined by tour co-founder Perry Farrell’s Jane’s Addiction, with Nine Inch Nails emerging as the breakthrough sensation. This year it was the summer’s must-see experience for the solidifying Gen X populace.

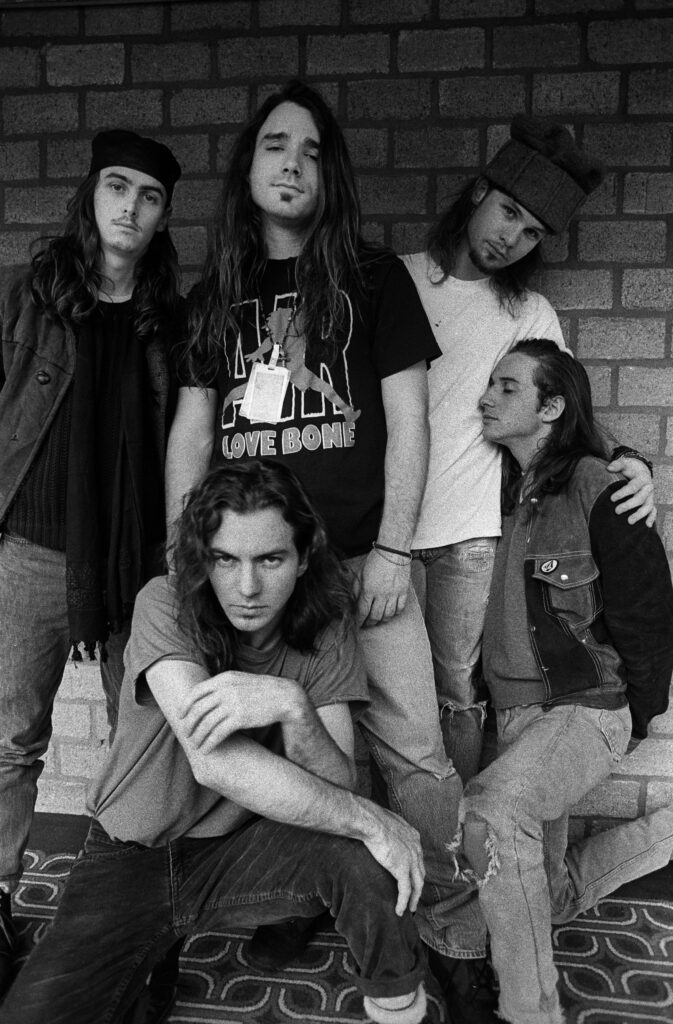

At the tour’s start a couple of months before, Pearl Jam was but an underground buzz. In the course of the trek, though, the quintet had skyrocketed to stardom, “Alive,” “Even Flow” and “Jeremy” were inescapable on alt radio and MTV. And with his combo of brooding, earnest intensity and perilous rig-climbing antics on stage, Vedder had quickly become an icon for a blossoming generation of disaffection and depression and, with that, an instant sex symbol.

No way was he going to escape from the backstage shelter untouched, literally, as hands reached out to make contact. He couldn’t deal with it.

“I can’t stand the little girls,” he had said, minutes before, in the interview we did for the Los Angeles Times feature. “They see you on TV and they think weird things and they just want to…to touch you or something really gross.”

He’d been in a steady, stable relationship for eight years at that point, he explained, and was not interested at all in what others offered.

But we walked on — no bodyguard or security or management representative as escort — and the adoring crowd thinned, or at least maintained a more respectful distance. On the last day of what had been a remarkable adventure for him, he was savoring what Lollapalooza offered, the full experience beyond the main stage.

In the interview, he’d talked about the suddenness of his fame, how it hadn’t changed him. “I’m still the same person,” he said. He didn’t want to be seen as a “celebrity.”

“As I see it, I think celebrities suck,” he said.

We strolled the concourse. He checked out food that fans were getting at the various booths, the sausages and burgers and tacos and funnel cakes, and the beers to wash them down. He had a look at band and fest merch stands and the various arts and craft vendors. He wanted to see who was playing the second stage, some of them old friends of his, some of them new friends.

And then, along the far side of the oval grounds, was an arc of tables given to various social and environmental activist organizations — Greenpeace for one, Planned Parenthood another. My then-girlfriend Mary was hanging out at the latter with her friend Debbie, who was volunteering. I brought Eddie by so they could meet him. He was as nice as could be, ignoring the handful of people who recognized him and sidled over and focusing on my friends. He looked at the pamphlets and seeing a clipboard with a sign-up sheet for anyone who wanted more information, he eagerly added his details.

A minute or two later, Debbie looked at the paper and got a look of shock on her face.

“Oh my god!” she whispered to me. “He wrote his home address and phone number here!” Sure enough, there was a Seattle residence and telephone next to his very legible name. Before anyone else saw it, Debbie slyly took the sheet and hid it from public view.

“Anyone could have seen it!” she said. “And just showed up at his house.”

Maybe this was the last gasp of his innocence. Maybe he knew it, that in the course of this tour his life had changed. Maybe simply writing his address on a mailing list was an act of defiance against that, conscious or otherwise. Regardless, there was a sweetness to it, something precious in this simple act.

In our interview before the stroll, though, another flash of his innocence, and of his antipathy for celebrity, carried a dark specter, an unwitting and now-chilling forecast. Talking about his small but much-noted role in Cameron Crowe’s movie “Singles,” set in the Seattle rock scene, he expressed dismay at the in-process mythologizing and fetishizing of that world of which he was now a core figure. He had told Crowe, he recounted, that if the film studio made too much of the Seattle grunge explosion in promoting the film, he would “buy a gun and become the martyr of the whole scene.” A bit more than a year-and-a-half later, Kurt Cobain did just that.

The next time I ran into Vedder, he was again mingling with the crowd at a concert, this time a much smaller one. It was November 1995 at the Cal State Long Beach Student Union, and he was hanging out at a show in which his by-then-wife Beth Liebling’s noise band Hovercraft (in which Vedder sometimes drummed, but not this night) was opening on a bill also featuring Cobain’s Nirvana bandmate Krist Novoselic’s new trio Sweet 75 and fellow Seattle band Sky Cries Mary.

The scene was somewhat surreal, given the three years since that Lollapalooza, and the year-and-a-half since Cobain’s suicide shattered this world. So many of the shards fell on Vedder’s shoulders, as he and Pearl Jam stood atop the new rock generation. It was a precarious — and unasked for — position, but the band found its way, balancing a determination to be artistically independent (as its music was already evolving in a way far removed from any “grunge” tag), commitment to its fans (the war the band had launched against Ticketmaster in 1994 regarding what it saw as excessive fees and venue control) and the disdain for the cult of celebrity that Vedder had expressed.

At some point during the evening, there was a tap on my shoulder. I turned and there was Vedder. No helmet this time, but he was wearing a baseball cap — and a sweet, bright smile.

Leave a comment