“Some of the stuff that’s in [the book] was written knowing that I may never play music again,” says Dave Alvin, chatting from his home in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake neighborhood.

“Or I may…. I may be dead.”

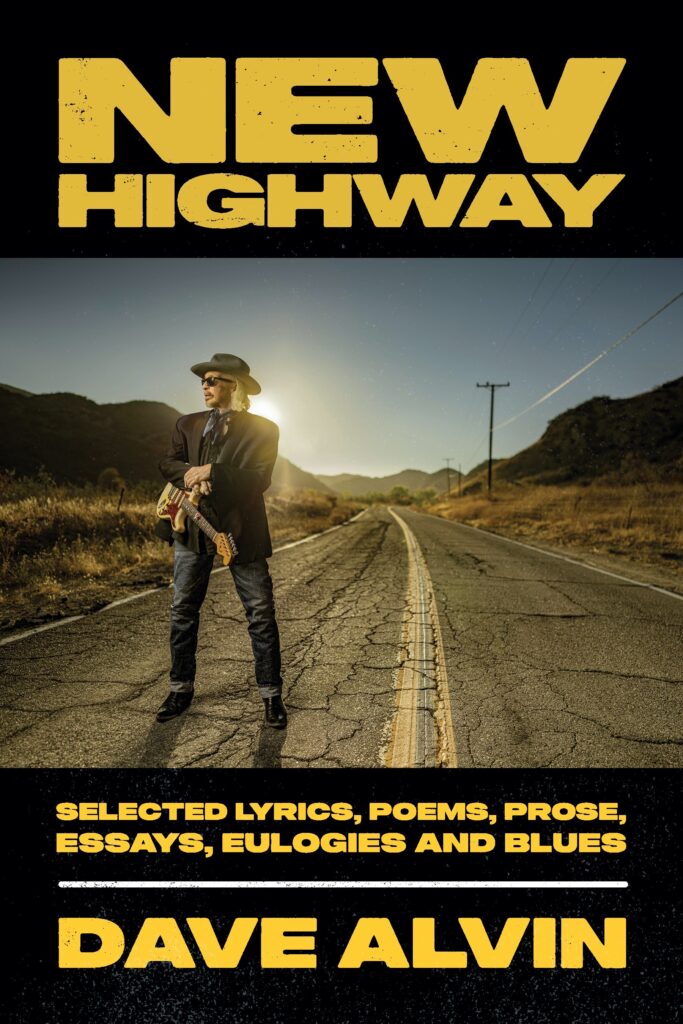

The book is New Highway: Selected Lyrics, Poems, Prose, Essays, Eulogies and Blues, a collection by the musician. There are stories of growing up in working-class Downey, a little southeast of L.A. There are songs included from his time as the primary writer and lead guitarist of the Blasters, which he co-founded with his brother Phil (“Marie, Marie” “Long White Cadillac,” the manifesto “American Music”) and from his solo career (“Fourth of July,” his quasi-theme “King of California”). There are colorful tales of road life and youthful daring, odes to the communal joys of music and tributes to departed friends, family and heroes, famous and obscure. All carry a personal edge, dark wit and literary depth, rich with experience and heart, in a voice as firm as his unaffected baritone.

But “dead”? He’s not being dramatic.

In early 2020, following a near-fatal bout with sepsis, Alvin was diagnosed first with prostate cancer and then stage four colorectal cancer, which had moved to his liver. Chemo caused neuropathy, making it impossible to play guitar for months.

“There were some dark moments where you’re like, ‘Well, I’m done,’ you know?” he says.

Not surprisingly, there’s a fair amount of death in the book — the title does say eulogies, after all, many written since he got his diagnoses. But there’s even more life in it.

In the final essay, the brief, beautiful “For the Rest of My Life,” he writes vividly of the rush he got when he was 15, white-knuckling in the back of a pickup with a bunch of guys heading to see blues guitarist Freddie King at the famed Ashgrove club on Melrose, a trip later commemorated in his 2004 song “Ashgrove” — and a feeling he never wants to let go.

There’s a line that could be at the end of this but isn’t, a wish he may not have dared put in writing: To be continued…

“I was supposed to be dead,” he says, with an allusion to writer Raymond Carver: “So everything until that happens is gravy.”

SPIN: What kept you going?

Dave Alvin: I have a good kind of stubborn streak. If I didn’t I wouldn’t have had a career! “Well, we’re not selling millions of records.” “Well, I’m not gonna stop!” It’s the same thing. You just keep plowing ahead, like a dumb mule.

The book doesn’t have chapters or sections. But many things are grouped, informally, by themes. One set relates to social justice. At the end of that you have your song “The Man in the Bed,” written when your father Cass [a union organizer] died.

Yeah, because that’s where I learned all that stuff. I learned it from my old man. My brother and I, people ask us, “What did you learn from Big Joe Turner? What did you learn from so and so?” Same stuff our old man taught us. And you can use the term social justice. As my old man would say, “People can be fucked.” And Big Joe Turner would tell you the same thing. Exactly the same words. So that’s what we learned. Certainly my brother can sing like Big Joe Turner if you asked him to. And I can play like Lightning Hopkins a bit. But those weren’t the important lessons. The real important lessons were how to view the world, how to survive in the world. How to have empathy. That’s where I learned that stuff.

In the essay “West of the West,” you write about your mother’s love for California.

My mom was a proud Californian. I inherited that from her. My old man came out here [from Indiana]. Rode the rails in the Depression. My mom didn’t view California as the Promised Land. It was just home. My mom really instilled the sense that everything past the Colorado River was “back East.” My old man had a different viewpoint. But my mother’s family was here. This is the land of the future. A couple of times I was on the verge of moving to Austin. And for a while I tried to live in Nashville. There were a couple of times I almost moved to Houston in the ‘80s. And almost moved to Boston. But one of the things that stops me is, well, you can’t go back East! The important word is back. California, you know, you go forward. West. Learned that from my mom.

[embedded content][embedded content]

You have highly entertaining pieces about things you wished you’d said to Frank Zappa, Ray Charles and [“Louie Louie” composer] Richard Berry when you had the opportunity, about how much they and their music meant to you.

It’s funny. I don’t think Zappa would have given two shits, although we did have a great conversation there on the Isle of Capri. And Ray Charles wouldn’t care one way or another. Richard Berry, though, I think I feel the worst about that one. I think that would have meant a lot to him. I have been shy since I was born. “Wanna go backstage and say hi to George Jones?” No. But Richard Berry, I still punch myself on that one. I’m like, “You could have said you loved [his lesser-known songs] ‘I’m Bewildered’ or ‘She Wants to Rock.’”

The pairing here of “Anyway,” written with [former band member] Amy Farris, and “Black Rose of Texas,” written for her [after she took her own life in 2009], is heartbreaking. Both songs have the underlying theme of finding it hard to deal with the world.

We’ve all known people who have trouble and don’t try. She tried and tried and tried. She was living one block over [from me] when she committed suicide. That still hurts. It’s hard to talk about. As a friend, as a band-leader, I felt like, did I put her in a situation that was too pressurized? Some people can handle being on the road, some people can’t. And when I do get on the road, it’s hard. It’s balls-out. Did I misjudge her ability to handle that? I’m not making any sense.

There are people [whose deaths] make me sad, and then there are people that just kneecap me. And how do you write about that?

The longest piece is near the end, the interview you did in the late 1990s for Mix magazine with Buck Owens at his Crystal Palace in Bakersfield, with an introduction written specially for this book, including the baffling mystery of stacks of $20 bills on his desk.

Buck did most of the talking. I never interviewed an artist before or since — well, I interviewed Jimmie Dale Gilmore for some West L.A. magazine, but that was two pals sitting around talking. It’s nerve-wracking. I wanted to write an intro for this that kind of explains what an important person he was, but also just how surreal it was. Not him, but just… life. I mean, I never could figure out those stacks of twenties.

Leave a comment