Analog music instruments were rendered largely outdated by the 1960s, anachronistic just as the advent of electronics fundamentally changed what music could be virtually overnight. With the creation of new instruments there comes new conduits to summon new sounds it taps into from the beyond, playing and teasing sonics into novel shapes, sizes and textures previously impossible. And no, I’m not talking about the synthesizer. There existed an earlier, more obscure electronic instrument, called the theremin.

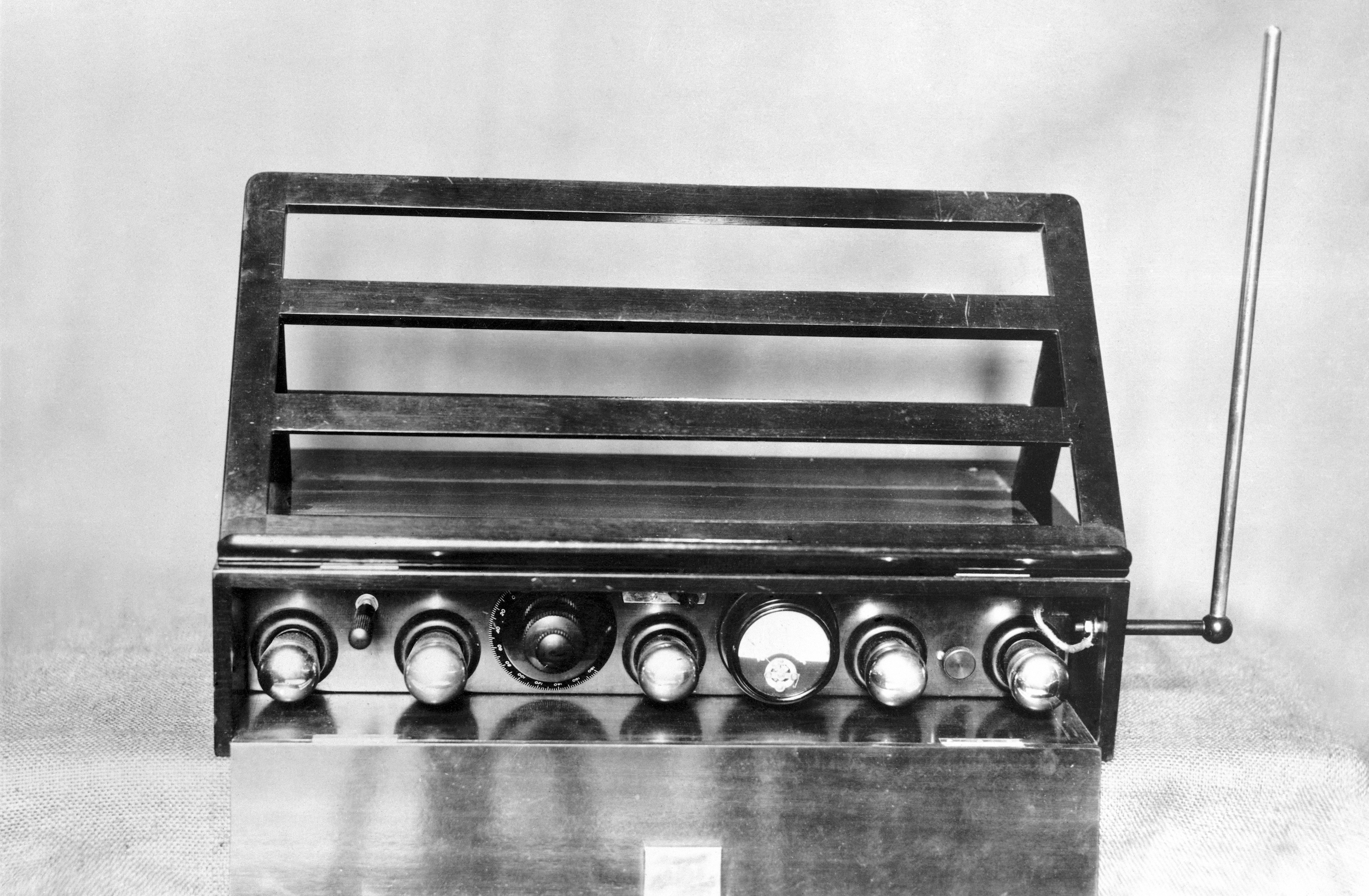

It was accidentally invented by Russian physicist Léon Theremin in 1919 while he was attempting to engineer proximity sensor devices for the Soviet government. His experiment was unsuccessful in what it sought to achieve, but its byproduct surpassed any other possible outcome, intentional or not. The first-ever electronic music instrument was born.

Understanding the theremin’s peculiarities

The theremin is a most unusual instrument: it’s played without physical contact. Let that sink in for a minute — you play the instrument without touching it! What in the world? How is this possible? For those who require visual evidence, here’s a clip of the theremin being played by its creator….

That was no parlor trick.

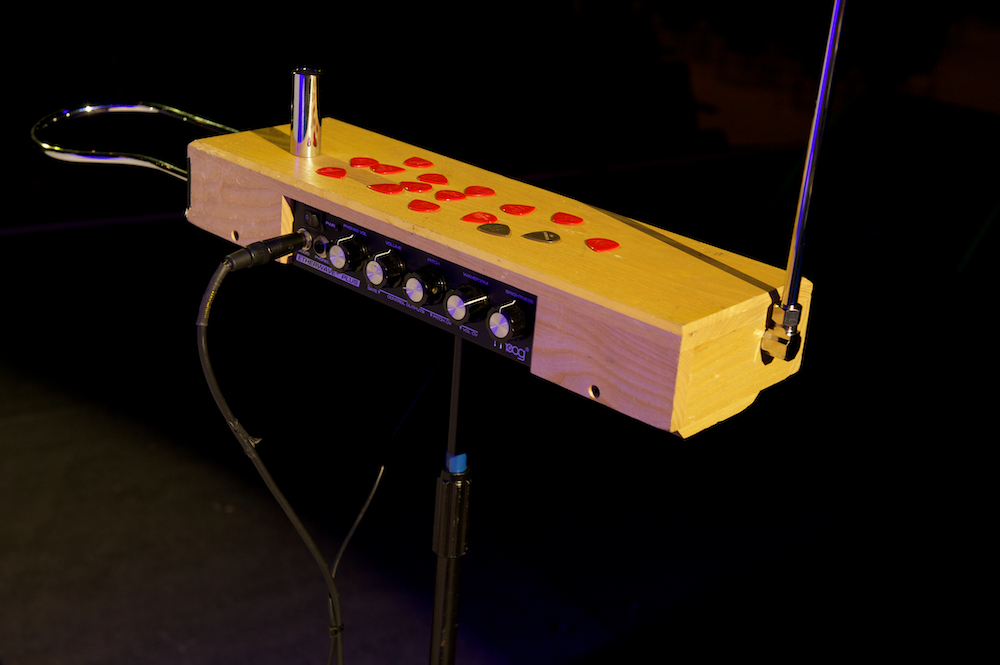

Its anatomy consists of a body that houses its circuitry with two metal antennae: one protruding laterally out of one side controls the volume and the other extending upward controls the pitch. You use both hands simultaneously, one for each antenna, to manipulate the interference of the electromagnetic field it emanates to produce a sound. The player, called a thereminist, ends up looking like a conductor of a ghostly opera from another plane or like a gesticulating voice coach training the ether to sing.

When played, the theremin conjures a lamenting wraithlike moan that can shriek into a point or croon out a bottomed-out bellow within a seemingly infinite palette of color. But that’s just a glancing, layman’s interpretation. On the other hand, Dorit Chrysler, professional thereminist and founder/teacher at the NY Theremin Society, quotes Léon Theremin himself to preface her own description of its eerie sound: “After his first concert in New York in the mid-’20s, he said ‘this new apparatus will free the composer from the despotism of the twelve-tone scale.’” She elaborates: “There is a lyrical component that can be extremely expressive.”

Its range is as broad as a synthesizer, so it’s not characterized by a single sound. It mostly depends on who plays it, reflecting the personality of the player and functioning like an extension of their voice through gesture, despite the irony of playing it without physical contact.

“There is no layer in between. It’s you creating the sound, your movement,” Chrysler emphasizes. “It’s not anything else.” And nothing passes through its detection. “It is the one electronic instrument that has the biggest potential for dynamic range because it’s so hypersensitive responding to the slightest motion of your body.”

Because there’s no implement dividing the musician and the instrument to produce a sound — like a pick or finger for plucking, a stick for striking, or a gust of breath into a mouthpiece — Chrysler likens playing the theremin to singing. “The person in the interface of the instrument is the voice…it can really sound [hysterical]. It can also be violent. It can be sugar sweet.”

Embrace without touching

The theremin’s hypersensitivity is its bane and its boon. Paradoxically enough, its ability to so easily emit a corresponding sound “even when you don’t think you move,” says Chrysler, is what makes it one of the most difficult instruments to play. Most folks are intimidated to even try it. It takes quite the amount of dexterity for it not to sound horrible but it’s also what affords its vast sonic scope. However, if you’re thinking about testing the waters, don’t let pre-trepidation sink in just yet. It’s “not easier or harder than a guitar or violin,” Chrysler says, “but you’ve got to get down with it and take it as seriously as any other music instrument.”

There isn’t a key to its mastery because much like the instrument itself, learning how to play the theremin isn’t one-dimensional. “There are various approaches [to] technique. But for me, I think there’s no right and wrong, and it really depends on what you want to do with this instrument.”

It’s almost like you have to invent your own technique to play it at all. It just provides a sort of amplifier for the poetics of your own “motor voice.” And no two voices are quite the same.

Standing the test of time

The theremin has made an indelible mark as the sound of mid-20th century sci-fi, most notably in the soundtrack to the 1951 apocalyptic film, The Day The Earth Stood Still where it first gained a name for its eeriness. Since then, bands from the psychedelia surge of the ‘60s as big as The Rolling Stones to the welcome landscape of experimental electro tapestry weavers of the ‘90s like Garbage have casually dabbled with the theremin. Its sounds have even seeped into television soundtracks, having been featured in the hit Marvel TV show Loki.

Although it’s already traversed the high-brow sphere of orchestral music and the low-brow sphere of pop, there’s still more untouched territory to explore. When asked what the future of the theremin could look like, Chrysler thinks, “It might be a good time to rip open the cracks and make space for this unorthodox new interface.”

She believes the theremin’s ongoing use “depends on who will dive into the instrument and take it to new visionary heights…hopefully some genius.” She admits that not enough people are exploring the theremin’s potential, but suggests that in the hands of a hyphenate artist like Brian Eno or Björk it could really breakthrough. “I’m just waiting for their call.”

Leave a comment