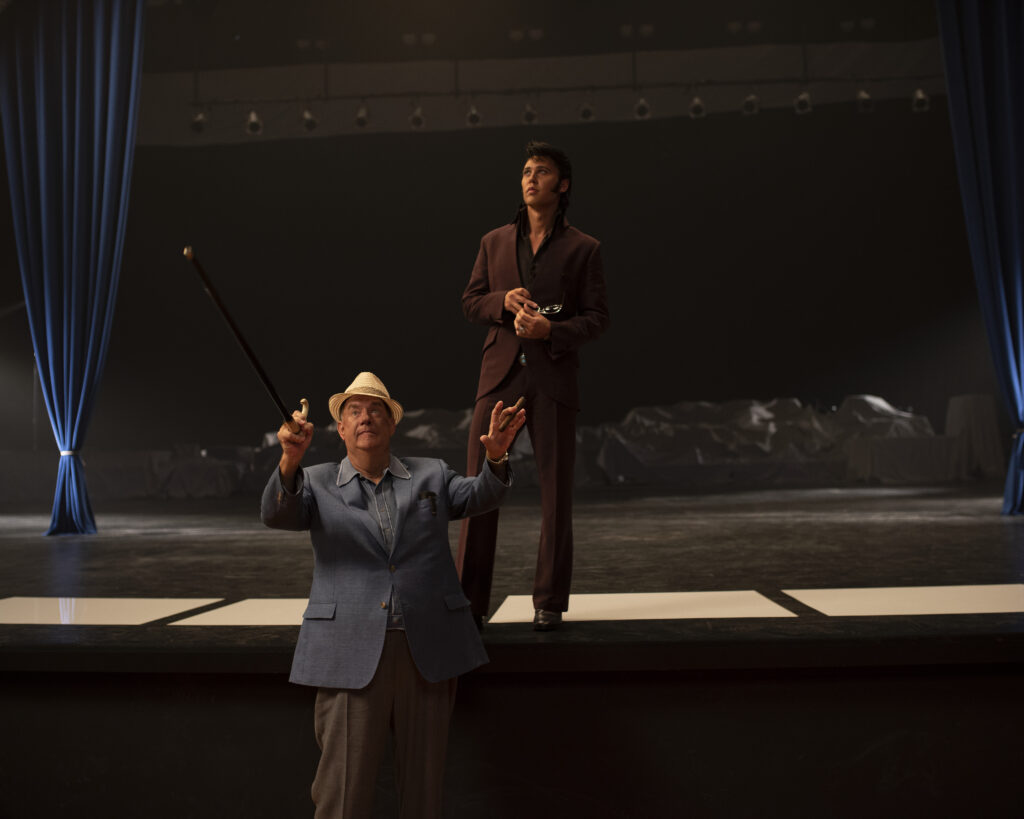

Baz Luhrmann’s unparalleled, and some would say over-the-top production style works very well to present the arc of Elvis Presley‘s career. The story is told through the eyes of Presley’s mercurial manager, Col. Tom Parker, astutely played by Tom Hanks. The Oscar-winning actor draws us in with his conspiratorial voiceovers, and then we see Presley’s puppet-like reaction.

The funhouse mirror scene when Parker woos Elvis, whether apocryphal, is a perfect metaphor for the career Parker shapes for Presley. Parker leveraged his astute judgment of human nature to pluck Presley from obscurity as a truck driver and move him quickly from a traveling circus-like roadshow to the pinnacle of mainstream popularity. Parker’s voiceovers consistently speak about his skill at conjuring up more snow (which tended to obscure clear-eyed observation). He founded The Snowmen’s League of America, but as the film shows, snowmen don’t last forever.

As with many excellent biopics, the origin story is the most crucial foundation of the film. Luhrmann (who directed, co-wrote, and co-produced the film) jump cuts back-and-forth in time; young Presley is seen becoming enamored of Black gospel music, from which the singer never separates for the remainder of his life. The first two-thirds of the film are magnificent, the second act ends with Presley‘s triumphant 1968 comeback special.

By the late ‘60s, Elvis had become irrelevant: his music was laughable and his movies worse. The film glances at the reason: Parker pulled all the creative strings and Presley was far removed from his core talent. Unspoken in the film was the reality that Parker demanded all songs recorded by Presley be published through Parker’s company, a revenue choice that nearly all songwriters eschewed. Hence, Presley’s recorded output lost relevance during the turbulent 1960s countercultural scene he triggered. But a few folks were able to whisper in Presley’s ear when Parker was unaware. Presley’s music improved and he delivered the electricity originally seen a dozen years earlier, when his 1968 comeback special aired to the largest TV audience that year.

You almost want Presley‘s story to end on that mountain top. Unfortunately, a long third act unspools. While Presley‘s income escalates so do his expenses, unbeknownst to him. Luhrmann and his fellow writers lean on too much exposition to tell the story of Presley’s struggles with matrimony, wealth, stimulants, and business. The glimmers of Parker‘s dark side are peppered during the first two acts and become fully visible in the third act. Hanks, playing against type, is fascinating as he portrays the duplicity of Parker, under mounds of jowls and padding. Austin Butler transformed himself into Presley and in the last few frames, the transformation is impeccable as evidenced by actual Presley footage interspersed with director Luhrmann’s recreations.

The film does a great job exploring why Presley never toured overseas, which has everything to do with Parker’s murky background. The film also reveals the birth of music merchandise. A particularly amusing scene has Presley sitting amidst a seemingly endless array of products thrust into the marketplace. Not only did Parker offer “I Love Elvis” buttons, he also sold “I Hate Elvis” buttons…why not make money at both ends of the fanbase?

Luhrmann is at the top of his game, with inventive transitions and brilliant set-pieces. His barrel roll camera work becomes a bit dizzying with overuse, but it admittedly works well when Presley hits Vegas.

In his autobiography, Bruce Springsteen wrote about how the sky cracked open when Presley appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show (an event curiously missing from this film). Springsteen described how before Presley, other than at Christmas and birthdays, life was always a bleak and conforming span of time, but after Presley, everyone wanted more love, more truth, more sex, more true religion, and the culture was changed forever. Seeing this film with my 21-year-old daughter was an excellent experience, as she became enlightened by the massive cultural impact Presley had. It’s probably for that reason alone that this film will command respect from even the purists who will find stylistic, chronological or musical anachronisms.

Luhrmann has recently announced a four-hour cut of his film exists, which delves into many incidents left on the cutting room floor (such as relationships with his first girlfriend, his early band members, and Richard Nixon). No word on whether the expanded version includes the famous meeting of Presley and Led Zeppelin.

The director has always been bold and brash with music in his films, and Elvis is no exception. Folks will spend endless time discussing what Tame Impala, Eminem, Swae Lee, Kacey Musgraves, Yola, CeeLo Green, and Doja Cat are doing here. But far easier to understand are Chris Isaak, Jack White, and Gary Clark. But isn’t that the point? To show how influential Elvis was? That may be the most clever way Luhrmann is able to confirm Presley’s immense influence on culture.

Leave a comment