Of all the artists that grew out of the fertile Greenwich Village folk scene of the ’60s, Karen Dalton has somehow remained in the shadows of firmly established stars like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. It’s not for a lack of effort on the part of Dalton’s friends and fans.

In the years since her death in 1993, her two studio albums — 1969’s It’s So Hard To Tell Who’s Going To Love You The Best and 1971’s In My Own Time — have been reissued multiple times, and several posthumous collections of her home recordings are now available. Dalton has also been namechecked as an influence by many of today’s musicians that fall under the folk umbrella.

In spite of all that, Dalton is still an unknown entity to most and even forgotten by those folks trying to keep the world’s listeners connected to music of all shapes and sizes. Like when friends and film producers Robert Yapkowitz and Richard Peete, deep into a heavy folk music phase, were out drinking in Brooklyn and wanted to dial up some of Dalton’s work on the bar’s digital jukebox. “We were able to find Fred Neil and Tim Hardin,” Peete remembers, “but no Karen.”

By the end of that night, the two men had decided to correct the historical record on Dalton by making a documentary about her, bringing both her music and her troubled life story into the light. They planned to have it done and dusted within 12 months. “That was six years ago,” Peete jokes.

The finished documentary Karen Dalton: In My Own Time is finally hitting theaters on Oct. 1. Much like its subject’s music, the film carries a quiet power and an unflinching honesty. Anchored by copious amounts of archival footage, photographs and journal entries (read in voiceover by Dalton acolyte Angel Olsen), the film’s portrait of Dalton is seen in varying shades of light and dark.

Dalton was an impulsive firebrand that quieted her internal demons via crippling addictions to drugs and alcohol. She was a hardscrabble Okie who had been married twice and had two children before she even made it to New York in her early twenties. Most importantly, she was an uncommonly talented artist whose original material and renditions of blues and folk standards — all filtered through the smoky tangle of her voice — left people breathless. As Neil once put it, “All I can say is that she sure can sing the shit out of the blues.”

For all the troubling tales recounted by Dalton’s daughter Abralyn Baird and collaborators like Peter Stampfel and Lacy J. Dalton (no relation), the documentary is ultimately celebratory, with an unusually strong emphasis on the music. At a certain point, the narrative stops dead as one of Dalton’s songs plays in its entirety. It’s a bold choice but one that felt necessary, according to Peete.

“Not having Karen to interview, we wanted to get her voice in there as much as possible,” Peete says. “You sit with the songs and really feel them and hear her and let her be a part of it.”

Unusually, too, the filmmakers chose to only include a few interviews with modern artists speaking on Dalton’s greatness. Some do make the cut, including Vanessa Carlton, members of Deer Tick, and Nick Cave who tells of listening to Dalton’s “Something On Your Mind” while driving around and becoming so moved, he had to pull over. “I was in tears,” he recounts to the camera. “I really felt a kind of shift within myself when I heard this song. It really changed how I looked at music. And I think that the Bad Seeds have been attempting to write that song for years now.”

As important as those insights were, says Yapkowitz, he and his partner deliberately chose to keep those interviews “to a minimum.”

“We never wanted it to be something that was just a bunch of musicians who didn’t know Karen. We wanted it to be centered around people who actually knew her.”

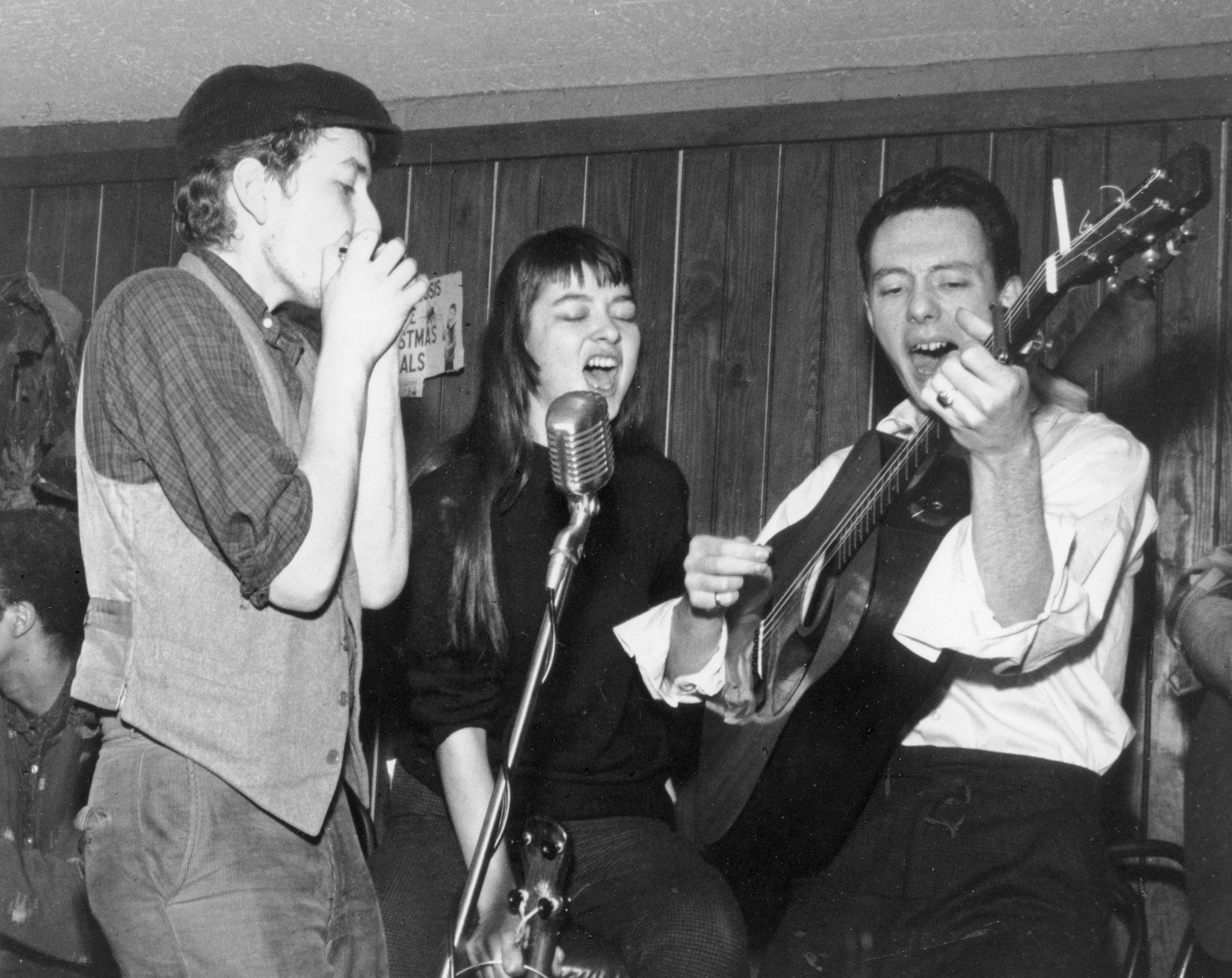

That said, some of those people did prove elusive. Dalton’s son initially showed some enthusiasm toward the project and wanting to appear on camera, but wound up ghosting the filmmakers. Their white whale interview, though, was Bob Dylan. The venerable folk icon was an early supporter of Dalton, performing with her during her first stint in Greenwich Village and, in the first volume of his memoir Chronicles, described her as having a voice like Billie Holiday and the guitar sound of Jimmy Reed.

“We asked Bob Dylan about 15 to 20 times,” Peete says, laughing at the memory. “We have a friend who works with his manager, so we did have a direct email. He was very responsive and very honest. ‘Bob doesn’t really do this kind of thing.’”

This documentary may do the trick of finally raising Dalton’s profile to the level of recognition and acclaim that she has long deserved, but it also reveals why she has long been a hard sell for some folks. In part, it’s the music. The sound of Dalton’s tremulous voice and hardened perspective can grate on the wrong ears. One editor that the filmmakers reached out to as a potential collaborator was excited about the project until they sent over some of the music. “He was like, ‘No way. I hate this so much,’” Peete recalls.

There’s also no redemption to be found in Dalton’s story. She played the music industry game as best she could, including touring in Europe with Santana in the early ’70s. However, she refused to bend to the industry’s will and let the strain of its pressure weigh down heavily on her. As her addictions took a tighter hold on her, she retreated to upstate New York and scraped by. During her final years, she was diagnosed as HIV positive and eventually succumbed to an AIDS-related illness in 1993.

The consolation will come as new fans are introduced to Dalton’s work and those folks who already knew and loved her get an even deeper understanding of where she came from and how that made her music sound as haunting and brilliant as it does. At the very least, Peete and Yapkowitz have been heartened by the response to the film from Dalton’s family and loved ones — particularly Karen’s daughter.

“When we first started the project, Rob found out where [Abralyn] worked and called her,” Yapkowitz remembers. “We said we want to do a documentary on your mom, and she said, ‘That’ll never work. Nobody can make it work. Nobody wants to watch a movie about my mom.’ Now she seems proud of the movie. She’s posting on social media about it. We were up for the challenge. Her saying people have tried and failed just made us want to do it even more.”

Leave a comment