This article originally appeared in the January 1986 issue of SPIN.

Ion Tiriac, tennis’ Transylvanian terror, who claims to be related to Count Dracula, is Boris Becker‘s manager. Immediately following the 17-year-old West German’s historic Wimbledon victory, Ion was heard to tell Becker, “Your life is over. You are born again with me.” In his spare time, Ion, whom Ilie Nastase calls a “tough guy,” eats shards of glass. Asked what kind of circumstances could provoke such dramatic displays, he says, “You use toothpaste? Toothpaste made from powder, powder made from sand, glass made from sand.”

Yes, Ion, but what about your digestive tract?

“You don’t digest, just eliminate.”

It’s mid-September, and Tiriac’s been stuck in Oklahoma for three days for the so-called Tulsa Challenge tennis exhibition. The matches, boasting Becker and Kevin Curren, this year’s Wimbledon finalists, and Guillermo Vilas and Vitas Gerulaitis, haven’t been able to muster more than a third of the 9,000 fans it takes to till the downtown convention center.

Ion’s losing money in this pasture, and the morning-drive DJ on KELI is saying Becker’s 144-mph serve would “whip the peewine and puddin’” out of his game. Ion’s committed to stay, but he’s spending most of his time working the phones, making deals, setting up more lucrative stops for Becker—keeping the faith in the wilderness until they can get back to the big towns and the big deals.

I had been inextricably locked in a chess game with Tiriac which began after Becker won the Wimbledon men’s singles title in July. My efforts at getting an interview amounted to a conundrum of mailgrams, hand-carried and Federal Expressed packages, and a torrent of phone calls and messages ad ridiculum. By September, though, it had become clear to Tiriac that I was as determined to get an interview as he was not to grant me one. We compromised. Ion made it difficult—to test me. I grew older.

The phone rings in my Tulsa hotel room. It is the surly, gruff monotone of the man who kept me at arm’s length during the U.S. Open. There is no “Hello” or “Wie gehts,” just “Tiriac.”

“Boris will not be able to talk to you tonight. He’ll be having something to eat, then he’s going to bed. Eleven o’clock tomorrow morning, O.K.?” End of terse message. Words are time and time is money.

The master of subterfuge calls me back. He’s changed his mind. Boris’s itinerary for the next day is tight. Quickly my allotted time evaporates as Tiriac recites: “9:30 Tulsa Tribune, 11:30 NBC local news, 11:45 KELI radio, 12:00-2:00 press lunch, 3:00-4:00 practice, 4:00-5:00 tennis clinic, 7:00-11:00 the games.”

There’s a knock at the door. Guillermo Vilas, who’s also holed-up in the downtown Westin Hotel, strolls in, suavely clad in off-duty Ellesse and Puma. “I have Ion on the phone,” I tell him. “I’ll be a minute.” Recently embroiled in a tempest over accusations he took appearance money, Vilas has been working aggressively on his own resurgence.

“Don’t let Ion give you a hard time,” he says, tossing back a disheveled head full of ringlets.

A striking contrast to his mentor/business partner, Tiriac, Vilas off-court is a charming philosopher, poet, and musician, who makes the thought of sharing Juanito’s Tulsa burritos and a few Carta Blancas seem agreeable. Vilas, who has known the enigmatic Count for 15 years, says, “Ion’s putting you off because he’s concerned that once you get Boris started he might ramble, and you’ll print everything he says.”

As we walk out toward the elevator, Vilas offers to answer any of my questions, “But talk to your boyfriend first.” Namely Becker. Wiseguy.

In the mid-’70s, Ion Tiriac’s will of steel helped shape Vilas into the giant-slayer who won 50 straight matches and 15 titles in 1977 and became the No. 1 player in the world. They extended their collaboration to the ownership of five tennis clubs and “the Becker acquisition”—Vilas put up half of the $250,000 Tiriac paid Becker to sign the West German athlete nearly two years ago. The 46-year-old Tiriac, who says he’s “too old” to coach, then enlisted Germany’s national trainer, Günther Bosch, to continue polishing Becker’s game, while the Rumanian Count juggles exhibitions, tournament appearances, endorsement deals, and the gypsy life like an armful of rackets.

Tiriac’s undeterred vision is welded to Becker’s image and game. Perhaps that’s his genius—single-mindedness. The coveted perks of stardom that Becker might enjoy—the cocktail parties, celebrity bashes, and jet-set scenes—must be cast off for higher goals. And if Becker’s memory lapses, Tiriac’s doesn’t. During Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, Boris had tickets to see Bruce Springsteen, but was “encouraged” by Tiriac to relinquish them each time as he advanced in the tournaments. “If Ion was another guy who just wanted the kid to be happy, he’d have said, ‘Yes, go to the concert, you’re young, you should do it,’” says Vilas. “But when you do things like win Wimbledon it’s not by luck. You can win one tournament maybe, but not Wimbledon.”

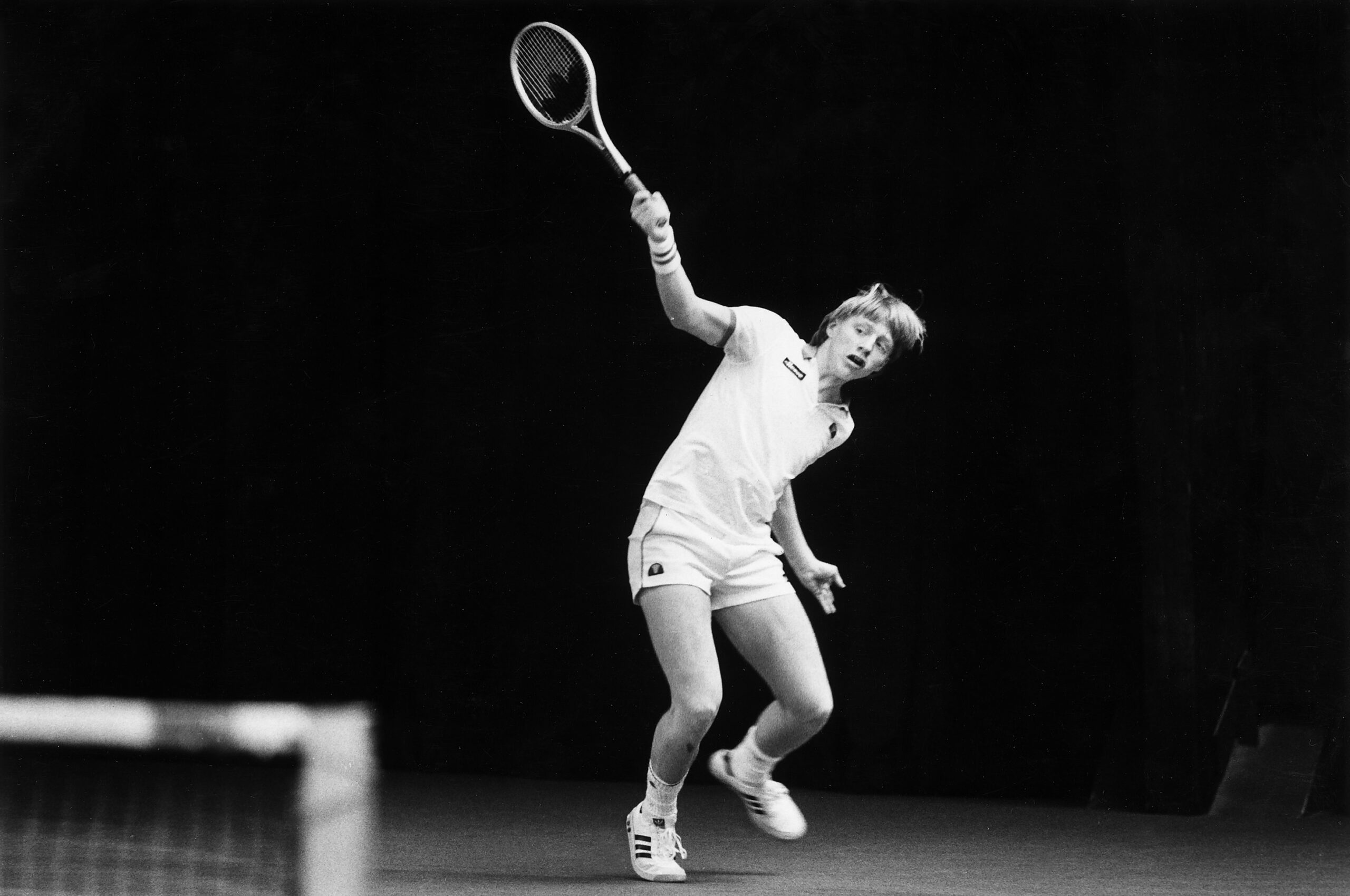

The morning after my arrival in Tulsa, Boris Becker, all 6’2″, 180 pounds of confident, yet angelic golden boy, is sprawled on a sofa in the hotel lobby. I’m reminded of what John McEnroe said after he first met him: “He seems so much bigger than you think.” Dressed in tennis casuals he’ll probably outgrow before his next birthday, Becker greets me for the first time since the U.S. Open, when his lightning serve froze the official Omega digital clock before he was unstrung by Joakim Nystrom in the fourth round. That night, in Flushing Meadow, New York, just prior to the match, Boris, reputed for his exquisite control of his game and his emotions, paced in the men’s locker room, looking uncharacteristically nervous. During the match he spat a litany of angry rantings in German at his Puma racket after every unforced error. Even umpire Mike Lugg caught hell from Becker. “One more mistake like that and you’re out!” Becker warned him. The press reported that a downtrodden Becker had, for the first time, acted his age.

Now it’s weeks later, and this morning Becker’s sunny and fresh-faced, sitting with the pleasant, understated Bosch, who brought Becker to Tiriac’s and Vilas’s attention, but seldom draws it to himself. Before we can begin the interview, Tiriac, hunching, stone-faced, walks up and says, “Be careful with a magazine like that, O.K.?”

“Careful of what?” I challenge.

He ignores me and says again to Boris, “O.K.?”

Then Tiriac, who when looking at you seems to have eerie peripheral vision, says, “Well, your magazine more,”—he hesitates, apologizing for his English—”more liberal than Rolling Stone.”

“You mean progressive,” I offer.

“Whatever,” he says brusquely. “You have one hour. You can get out of him even what his mother fed him when he was six months old.”

I remind Tiriac I was granted three hours, and as he quickly shuffles away, I note that scoring popularity points with outsiders doesn’t interest him; the only points that turn his head are those his players earn to enhance their standing. Bosch, who speaks no English, quietly walks off behind him.

Becker says he is closer to “Güntzie” and Tiriac than he is to his own father. On the Tonight show, he had said he felt like he had “three daddies.” He now tells me that if there’s any resentment felt by anyone around him, it’s by his father. He endearingly mimics 50-year-old Karl-Heinz Becker: “I’m your real father, not them.”

It’s apparent early into our conversation that Becker wrestles with more than a few of the attendant distractions and complications of being a superhero. For one thing, he can no longer live in West Germany, where all national broadcasting was preempted to televise his Wimbledon and U.S. Open matches to 20 million viewers. Lufthansa, the national airline, announced his scores to passengers in-flight.

“I cannot walk on the streets, it doesn’t matter if it’s Munich, Hamburg, or Leimen [his hometown],” says Becker. “If I go out, I wear disguises in Germany. I’m living in the world now, and it’s hard sometimes for my parents to understand what’s going on. I’m 10 months on tour, and they see me like two months. In the beginning they say, ‘O.K., for sure,’ but they didn’t realize it was the reality. It’s still tough on them, but slowly, slowly they get used to it. It’s not too bad in the U.S., but it’s getting worse here every week.”

When he does go home, the enfant célèbre is conspicuous by his Blues Brothers punk shades, and the company he reportedly keeps, which includes German TV personalities, Princess Stephanie of Monaco, and, more recently, attractive pro-tennis player Susan Mascarin.

A day doesn’t go by in Germany when Becker isn’t in the dailies. “Boris says anything,” claims Associated Press journalist Nesha Starcevic, “and it gets a headline.” Sweetheart though he remains to a majority of his countrymen, a small backlash has stirred up against Becker. Recently, a West German postal worker, annoyed by the Becker brouhaha, started an anti-Boris fan club that plans to give out T-shirts with “Who the hell is Boris Becker?” across the front. In less than a month, 148 members joined. Says the club’s founder, Juergen Pfaffe, “All this monkey business about this girlfriend here and that princess there, that’s enough!”

It’s a late Tuesday afternoon and downtown Tulsa is oddly tranquil. A softening sun silhouettes Becker who, seated and relaxed, conveys quiet composure and tangible magnetism. Ilie Nastase had told me: “He’s the most mature 17-year-old I ever met.”

“I was on the phone two days ago with an old school friend,” says Becker. “He was talking to me like a hero, like an idol. I tried to be like it was two years ago . . .” His voice trails off. “It’s hard for them—they don’t know how to treat me anymore.”

“Does that sadden you?”

“. . . life goes on,” says Becker matter-of-factly.

So, too, his Concorde pace. “I’ve not many close friends because I’m one week here, one week different place. Acquaintances, yes, but not close friends.”

The lonely hotel hours—between matches, during rain delays—the stress, and the press are made bearable for Becker by his constant companions, Walkman, American Top 40, and MTV. (He’s got a particular penchant for video animation, such as Dire Straits’ “cartoons.”) Tiriac had listed the increasing encroachments on his client’s time: “In addition to 40 weeks on tour this year, we now have more responsibilities to the game and the media. It’s getting out of hand, the over-publicity he has, particularly in Germany. It’s becoming ridiculous.” Becker has even gotten offers to do a couple of movies, one of them about Renée Richards, the transsexual tennis player. But Becker and Tiriac are aiming for the long-term volley that a career sidetrack could impede. “Maybe when I’m 30,” says Becker.

The intense publicity may have gotten in Boris’ way during the U.S. Open. The draw produced the likelihood of a McEnroe-Becker face-off in the quarterfinals, and as the tournament progressed and both players kept winning, the pressure and anticipation built. Before the outcome of the fourth round, CBS, assuming the champs would meet, preempted its programming for the night of the anticipated match to televise it nationally.

“In the players’ lounge everybody was talking about it,” says Becker. “Other players and guys in the locker room who didn’t like McEnroe kept saying, ‘You’re going to beat him.’ And maybe in the back of my mind I was thinking about playing McEnroe during the Nystrom match.”

But it wasn’t to be. “I did everything possible I could during the match. I was fighting, I was diving. I tried everything, and it just didn’t work.” Instead, Becker lost his Ellesse shirt to the cool Swede Nystrom. “After the match,” he says, “I went back to my hotel room and I got so pissed off I lost, I was doing sit-ups and exercises for an hour or more.”

During a press conference at the U.S. Open Becker had expressed eagerness to play McEnroe. Now he tells me, “Hopefully, I’m not playing him in the next 10 years, but I think I have to.”

“You mean you’re not looking forward to it?”

“Of course, a little bit, because he’s the best player. I could learn a lot from him, but he’s, at the moment, a little bit too good, maybe.”

But Tiriac concedes nothing in answering questions about Becker’s readiness to face McEnroe in a tournament. “Which McEnroe?” growls the riddle master. “The McEnroe who played in the Masters, the McEnroe who played in the U.S. Open, the McEnroe who played Wimbledon? Boris has a good chance to beat him. McEnroe, for one reason or another, up and down.”

(But in two recent exhibitions, Becker played the McEnroe who has dominated tennis since the retirement of Bjorn Borg, and lost both. “You don’t become No. 1 by winning one tournament,” said McEnroe.)

There’s a growing concern, though not on Becker’s part, that if he continues to throw himself around the court like a rag doll, he might sustain injuries that could set back his game (and the solid gold Ebel watch he wears on court) more than a few hours. But he’s oblivious to words like ‘fear’ and ‘pressure.’ Or so he says.

“To be No. 1 in tennis you have to be not normal. I’m not normal in my physical, in my head, in everything.”

In the nearly two years that the triumvirate of Becker, Tiriac, and Bosch have collaborated, Becker has reached the ’84 Australian Open quarterfinals and the ’84 Italian Open semifinals. In 1985, he has won Queen’s Club, Wimbledon, and the Association of Tennis Professionals Championship, and made the 1985 U.S. Clay Court and Tokyo Seiko semis, and the Davis Cup finals. He’s also won a number of exhibition titles. Between prize money, BASF, Puma, and Ellesse endorsements, personal appearances, exhibition money, and other marketing strategies brainstormed by Tiriac, one report pegged Becker’s 1985 earnings at $3 million. “It’s ridiculously low,” says Tiriac.

There is a formula to the brain trust’s success. It is contained in “the program,” a plan for the development of the consummate tennis property to which Becker, Tiriac, and Bosch have dedicated themselves unconditionally. While the tennis prodigy says he is not materially motivated, months before his 18th birthday, Tiriac bought his protégé a Monte Carlo address. By maintaining a six-months-a-year residence in Monaco, Becker reportedly only pays 19% of his earnings in tax compared to the considerably feistier 56% income tax he would otherwise pay in West Germany.

As long as he calls Monaco home, Becker may also elude Germany’s mandatory draft (an 18-month obligation). Translated: he may not have to trade his Puma Pro-line for a Deutschland rifle. Tiriac’s (and Vilas’s) retirement fund would also remain unscathed.

Tiriac seems defensive about Monte Carlo: “I am based there. The German Federation didn’t want to have any economic part in his development, and I had to do it myself. It’s also easier to do it from here than from Leimen.”

Boris is oblivious to, and perhaps uninterested in, his manager’s Machiavellian master plan, but he is intimate with the rigors of his daily regimen. “With Ion it’s black and white. When I’m practicing, it’s nothing else, just practice. If I don’t want to practice, then I should take some time off. But when I’m ready again, I’m practicing six hours a day.

Though he says he trusts Tiriac’s professional instincts totally, that wasn’t always the case. The first time Tiriac suggested Boris’s footwork on his serve was all wrong, Becker countered, “What the hell are you talking about? I have a very good serve.” Tiriac, who claims you have to prove everything to the skeptical athlete, drew illustrations of how, with different foot positioning, Becker could move forward faster. Becker’s own experimentation with the new plan finally convinced him that Tiriac was right.

Echoes Ion: “I think we have a lot of respect for each other. That’s the way we are probably going to survive.”

“I’m not an easy player to coach,” Becker admits, “’cause I don’t like when somebody’s always talking to me: ‘You have to do this, you have to do that.’ If I’m missing a ball 10 times, I need some help and I ask Günther what I’m doing wrong, but he knows how to back off.”

“The program” has caused some conflicts with Elvira Becker, who disagrees with her son on the subject of deferring Boris’s education. Becker has two and a half more years to go to take his abitur (the mandatory West German university entrance exam), but Boris, who’s already fluent in English, says, “If I really need it to know more about life to succeed, then I’d do it.”

Clearly, when Tiriac recently said, “Tennis is 80% head, 20% legs,” he wasn’t considering enrolling Boris in night classes at Heidelberg University.

I ask Becker how he psyches himself for competition. Verbal sparring with Tiriac helps, he says, but he often pumps himself up for a match by “thinking about Sylvester Stallone.”

“As Rocky or Rambo?”

“Both, but more Rocky when he’s practicing on the beach,” Becker says.

With those who say Becker may have won Wimbledon too easily, the usually patient Vilas is impatient. “Look, I think philosophy’s very interesting and history is very nice,” he says. “Napoleon lost Waterloo ’cause somebody forgot to say to part of the army ‘Attack,’ whatever. You can write history afterwards, but some people are part of it. Easily or not, he definitely won Wimbledon, and in 10 years that’s what will count. You have to say the kid is good.”

Unlike the three years of hard work and nurturing Vilas required with Tiriac, Becker’s transition to the major leagues was fast. Two years ago when he turned pro, Becker’s ATP ranking was 529. But under Tiriac, who has coached or managed not only Becker, but also Vilas, Nastase, Adriano Panatta, Manuel Orantes, and Henri Leconte, Becker’s game rapidly developed. Tiriac ranks his newest pupil at the top of that distinguished class in drive, raw talent, charisma, and, maybe, eccentricity. “From the beginning,” Tiriac had told me in one of our phone conversations, “Boris and I had a deal that he’s not jumping over the board when he wins.”

“Ion is there to make sure the kid doesn’t get strange and crazy and lose it,” says Vilas. But somehow an image of Boris popping bottles of German Sekt champagne doesn’t quite compute.

“At the end of ’84 when I won the Australian Open quarterfinals,” says Becker, “I was a bit shaky. I couldn’t feel the ground anymore. But then I lost a couple of times,” and he was reminded how fragile triumph-induced euphoria can be. It’s that same volatility that Becker says excites him about the game. All the champs lost the U.S. Open this year: Martina, McEnroe, Chrissie, Becker.

“There are three different Grand Slam winners now. That’s why I like tennis so much. One day everything can change.” He should know.

There’s not much normal about a kid whose architect father helped build the only tennis courts in Leimen, on which Boris played before reaching the age of reason; a kid who a year later (aged 8) would play the game competitively, and by 14 decide to give up high school and its social life to make a lifetime commitment to tension-strung gut and lint-wrapped rubber balls; who says he learns something from every match he loses; who’s almost abnormally uninterested in the lucrativeness of being ranked fifth in the world and what that can buy—except that it means being able “to replace one or two Walkmans a week because,” as Tiriac says, “he’s losing them all the time and can’t live without music.”

“Maybe I’ll have a different opinion three or four years on the tour,” says Becker emphatically, “but, at the moment, I’m not playing tennis for the money, as long as I don’t want to buy a house, a plane, or a ship.” But he qualifies that judgment. “Maybe the security you have from so much money is nice.”

In Europe, where checkbook journalism is rampant, Becker was paid $35,000 by a German magazine for an interview. He claims such proceeds have at times gone to charities for the disabled. And although he fails to mention it, he added $63,000 to the $12,750 the auction of his winning Wimbledon racket raised for mentally handicapped children.

He says his ultimate fantasy is “having a relationship with my children not like father and son—like friends. I always wanted to be proud of my father, but after Wimbledon I wasn’t anymore, because I needed some help and I don’t have so many friends. I thought my parents were very good friends, but they made some mistakes.

“After Wimbledon my father was giving press conferences and magazine interviews, and I said, ‘Hey, man, you are my father, not my tennis coach. You can talk to me about electronics, or you can say when I have to go to bed—but not that you’re talking to some journalist saying, ‘He’s playing good forehand.’ That’s not his job. We had a long discussion, and he found out I’m right. Now everything’s OK . . . In some ways, I already have more life experience than my father, and he’s 50.”

Becker’s been called “warrior” and even “bully” when it comes to his increasingly assertive court behavior, but now he concedes: “Two years ago I was pretty bad-mannered on the court; throwing the racket, screaming, and worse. But then Ion, Güntzie, and me, we talked about this problem and we found out that when I’m losing my temper, for the next five points I’m not playing good tennis.”

Becker maintains his Teutonic, clear-thinking pragmatism as our conversation moves into a discussion about off-court habits that have gotten in the way of more than one pro’s game.

“People who are taking drugs need sometimes to be happy. I don’t need drugs or alcohol to make me happy. But if anyone asks me [to try drugs], and Ion is going to know, they won’t be happy again anymore.” His voice is facetiously threatening.

“Would he use physical force?”

“Yah, maybe . . . he’s stronger than I am.”

“How do you know?”

“We’ve had some fights,” he chuckles, as I realize Becker, who in the early days was “afraid” of Tiriac, has developed an unmistakable camaraderie with his mentor. It’s also clear Rocky and the Rumanian Rambo have whiled away some of their off-hours in horseplay.

“So, he’s stronger?”

“Until now, maybe,” Becker explains, “but I’m getting stronger, he’s getting older.”

Even heroes have heroes, and I wonder who are some of Becker’s.

He pauses—longer than any question has yet prompted him to—and appears to be more interested in continuing the interview than in leaving for the night’s matches which have already begun.

“The Pope,” Becker says thoughtfully, claiming he may be granted a private audience with John Paul II this year. Although he admits he’s not a churchgoer, he says, “I want to see, I want to touch him. He inspires me. He seems like something else, not a normal human being.” But of the Vatican he says, “Everything is too rich there.”

That night at the Tulsa tennis “shootout” there’s something superhuman about Becker as he blitzes aces past Kevin Curren with the kind of ammo that has the corporate types in the box seats ducking when their teeth aren’t chattering. Even CBS’s Brent Musberger observed, “Coming against Becker’s power is like taking on a Dwight Gooden fastball.” He attacks every ball, because every ball counts.

And Golden Boy’s got chutzpah, too. Since Wimbledon he’s progressively displayed more of it. During this last match in Tulsa (unofficially billed as “Wimbledon II”), he questions a lineswoman’s call. He walks up to the grey-haired official and, with his arm wrapped around her, sticks his face in hers and asks, “Are you sure?” He also wins the match.

Jimmy Connors once said, “There’s no view like the view from the top,” and while Becker still has more dues to pay before he gains admission to that club, his performances seem to say, “It won’t be long now.”

In the meantime, January’s Nabisco Grand Prix Masters in New York—and the challenge of the top 16 singles players pitted against each other for a $500,000 purse—awaits the phenom.

Leave a comment