Cory Wong is in full professional podcaster mode. Seated in his Minneapolis studio with headphones on, he looks into a giant microphone stationed on his desk nearly as often as he looks into the camera. It’s a classic podcaster stance—and hardly surprising, given that over the last six years he’s hosted more than 100 episodes of the“Wong Notes podcast.”A self-proclaimed “guitar guy,” he has his own limited-edition signature Fender Stratocaster, plus his own guitar course. Behind him on screen, I can see a stack of guitars—and a Louis Vuitton shopping bag I’m dying to peek into. On the podcast, Wong invites friends and heroes alike to talk shop. His guest list spans Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, Nuno Bettencourt, Jason Newsted, Wolfgang Van Halen, and plenty of other marquee names.

On his YouTube series, “Cory and the Wongnotes”—now two seasons in—Wong’s irreverent personality really shines. He describes the show as “My version of ‘SNL’ meets ‘The Late Show,’ if the musicians took over with sketch comedy and performing and recording live on set and interviewing other musicians.” That sensibility reaches its peak in the hilarious stand-alone video “Wong on Ice!,” where he plays multiple characters, hockey, and guitar. It’s required viewing.

“My music is one outlet,” he says. “But with instrumental music, you don’t always get my personality the same way that you do when you watch me on some of my YouTube videos. I like doing those because it allows me to explore and express those different parts of my personality that I don’t do with music.”

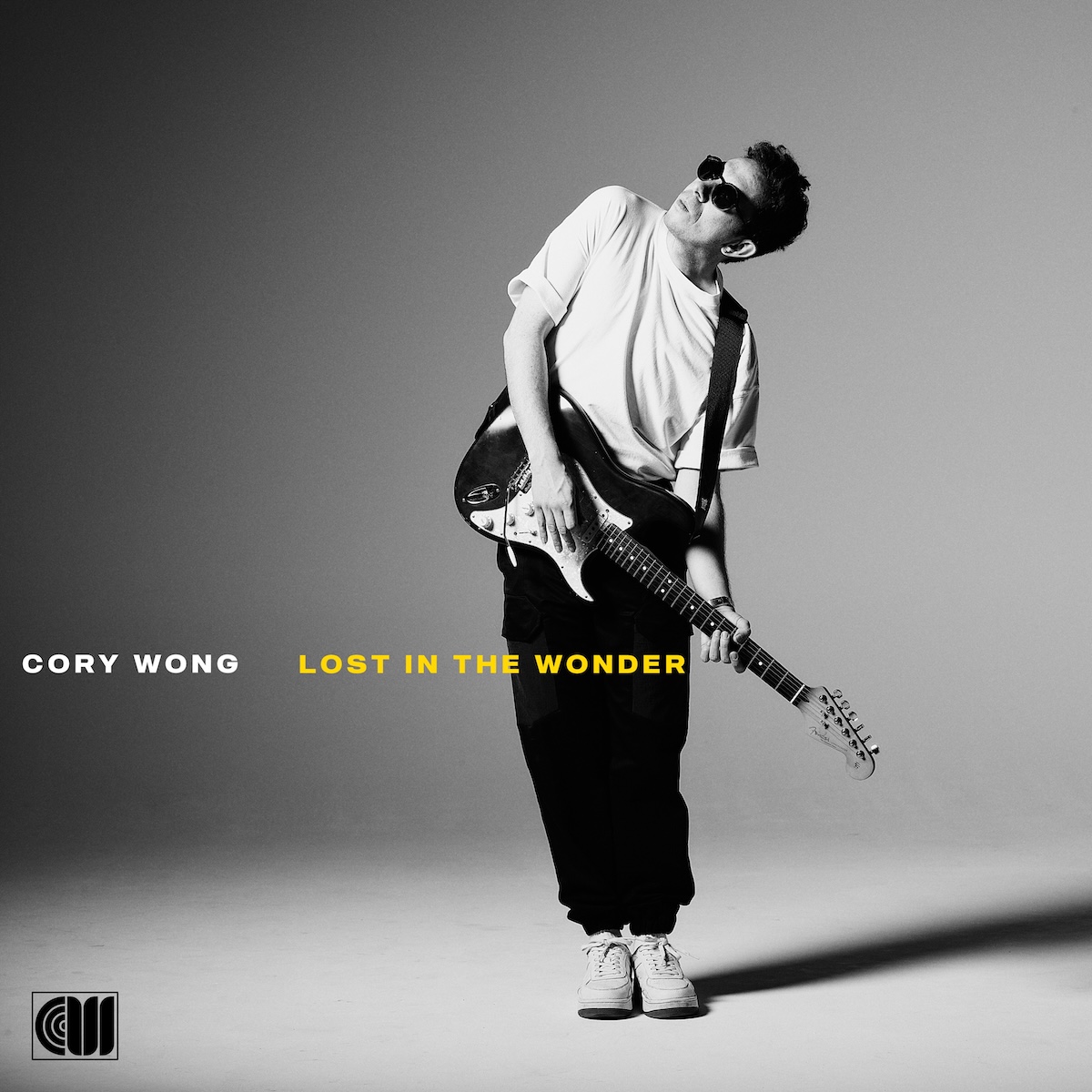

In a word, Wong is prolific. He’s released 14 solo albums, eight with his band The Fearless Flyers, and collaborative albums with Dirty Loops, Dave Koz, and Jon Batiste—the latter earning him a Grammy nomination. That tally doesn’t even include his work with Vulfpeck or the multiple live albums that capture his animated onstage presence. His latest release, Lost in the Wonder, marks a left turn for Wong, whose music typically lives in a jazz-funk, retro-leaning world. The album features collaborators Taylor Hanson, Stephen Day, Devon Gilfillian, Cody Fry, Theo Katzman, Benny Sings, Yam Haus, Louis Cato, Magic City Hippies, Elysia Biro, and ellis, resulting in a vocal-forward record that embraces ’80s-era pop in the best possible way.

Day, Gilfillian, and singer-songwriter Marc Scibilia will join Wong on select North American tour dates beginning April 11 in support of Lost in the Wonder. The album’s stylistic shift feels tailor-made for Wong’s onstage banter, which rivals his guitar playing. He radiates the zany energy of an ’80s sitcom character, paired with a natural leadership quality that carries into our conversation. He steers the interview much the way he runs his podcast. Frankly, I’m happy to hand over the reins. Wong knows exactly what he’s doing.

Lost in the Wonder is much more vocal-forward than your previous releases. What led you in that direction?

My last album was all instrumental, and it was a collaborative album with the Metropole Orkest, an incredible orchestra in the Netherlands. That was new territory for me, because I was writing for an orchestra and a funk band, and, to get one of the top orchestras in the world to cover that side of it, along with the hard-hitting funk ensemble that I’ve got, and to do those two worlds justice. I wanted to explore that artistic space because that’s what keeps me excited: growing as an artist, challenging myself, exploring different parts of my artistry.

On this album, I wanted to start by exploring my artistry as a producer, as a writer, as an arranger, that happens to also play guitar. Naturally, I hear the guitar in so much stuff, because my ear gravitates towards it, and it’s what I do. But with this album, I wanted to challenge what I can bring to the table, drawing from different influences of mine, everything from Earth, Wind & Fire to Steely Dan, Prince, Jamiroquai, and Bruce Hornsby. The collaborations were really fun because I got to write with other people that I admire and are friends of mine.

How did you decide who you wanted to work with on this album?

When I started to get intentional about this album, I went through my phone and my list of all the people that have said, “Let’s get together and work on something,” and who are the ones that I think actually meant it, and who are the ones I see something in their artistry that hasn’t been explored yet, and I see something they could draw out of me that I haven’t done yet.

My managers are like, “We have connections with this person, and this person, or this person said they want to write with you, and I think it would be really great for you if you did.” I’m like, “Yeah, but I don’t love their music.” Imagine there’s this person with a huge fanbase that buys everything they’re a part of, but I hate their music. It’ll mean all kinds of great things for my numbers and blah, blah, blah, but then you write the song, and I mean, God forbid I ever have a hit song, something that everybody in the world likes, but I don’t love the song and now I got to play it for the rest of my life. I would dread that scenario. I would be so bummed.

When I’m picking the people I work with, it’s people that I genuinely want to work with. I want to get in the weeds, artist-to-artist, with somebody. You look at somebody like Taylor Hanson, and a lot of people have immediate assumptions about Hanson and Taylor Hanson and what he’s capable of. But listen to this tune that we wrote together, and all of a sudden, you get the depth of his influences and the depth of his artistry. I bet a lot of his fans don’t know that he’s capable of singing [in the] pocket and stacking harmonies with himself. I felt like I got a lot out of him, and he drew a lot of things out of me. That, to me, is what collaboration is about. Those are the kinds of people I love collaborating with.

Artists often move between genres and styles from album to album, and fans choose to follow and trust those shifts. Do you feel like you’re experiencing that?

It’s a fun time to be an indie artist. I’m not on a label, so I can just say, “This is what I really feel I’m being called to do right now. This is what feels right in my artistry. This is what’s exciting me and what’s going to keep me passionate about what I do, and it’s going to help me grow.” The audience can tell when you mean it, and they can tell when you’re phoning it in. People are smart. Audiences are smart, especially if they’ve seen you for a while. And my fanbase is clever. They’re creatives, they’re wonderful, and they’re open to new stuff. Some people are like, “I didn’t love the orchestra thing, but dang, it was incredibly well done.” Other people might say, “I’m not into all the vocal stuff. I’m into the instrumental stuff, but I know that I’m going to get that when I see him in concert.” I think what you’re saying is, people can find avenues of your artistry they align with, but will trust who the person is and what their artistry is if it’s authentic and if they mean it. I did a residency at the Blue Note with Joshua Redman, who’s one of the most iconic, legendary jazz saxophone players of all time. We recorded that and it’s going to come out following this album. It’s part of who I am as a whole.

Your stage persona comes through clearly on your live records. How do you think about that in relation to jazz, where the focus is often more on the music than on between-song banter?

I got my start in music being like a Warped Tour kid, a skateboarder, snowboarder kid. I loved watching Blink-182 and Green Day, Chili Peppers, all these bands with big personalities. MTV was my babysitter. Watching all that stuff, being entertained, and absorbing art at the same time was not a foreign concept. When I started to get into the jazz stuff, like you’re saying, there’s so many artists that are incredible, but I feel like they’re just playing up there for each other. There’s a validity to that, but sometimes I felt, “Do you guys even want to be here? Is this a bummer for you to do?” Then this group in the Twin Cities, when I was a teenager, called Happy Apple, the drummer was always such a character on stage. So much of why people would go see them play, beyond making this incredible art, is he was a fun and funny person. He was the first person I saw where it was like, “Oh, we have permission to have fun and not take ourselves too seriously, yet at the same time, be very serious about the music and the art.” That has stuck with me through my entire career. Especially with the jazz world, it’s such a serious art form, this intellectual thing that people take it, and themselves, often so seriously and oftentimes as they should. But I like to have fun. I like to have a good time with my friends. Music is something that is very visceral for me, but you can be very deep with a smile on your face.

Do you think your personality helps make this kind of music more accessible to people who might not typically gravitate toward jazz?

It’s an artist’s duty, in some way, to think about the audience’s experience. Who’s coming to the shows, and what do you want them to leave with? I think a lot of people that do what I do are like, “I want you to leave this show and talk about how great I am at the guitar.” I don’t really care about that. Sure, you’ll find out that I know what I’m doing, and that’s fine, but I want you to leave having a great time and having something that really sparked something for you with music. Making this new album, it was like, “How am I going to get my personality across? How am I going to pull this off live?” So much of the stuff that I do live is instrumental, but how can I make an album that features me as a producer, but not be so pop-y? How can I sneak vegetables into the recipe? Even in the stuff that’s really pop-y, I try to make it interesting musically. The song form and the melody might be a little more of what is “radio friendly,” but where you think a bridge is going to go, and where the ear wants a bridge to go… I’ll give you that satisfaction, and I’ll be that predictable, but what I’m going to do is I’m going to make a modulation up a minor third for it, and it’s going to be a guitar solo instead of a bridge. It’s a little bit of a perk to the ear.

Leave a comment