Epiphanies come, as epiphanies do, in unexpected and often far-flung settings.

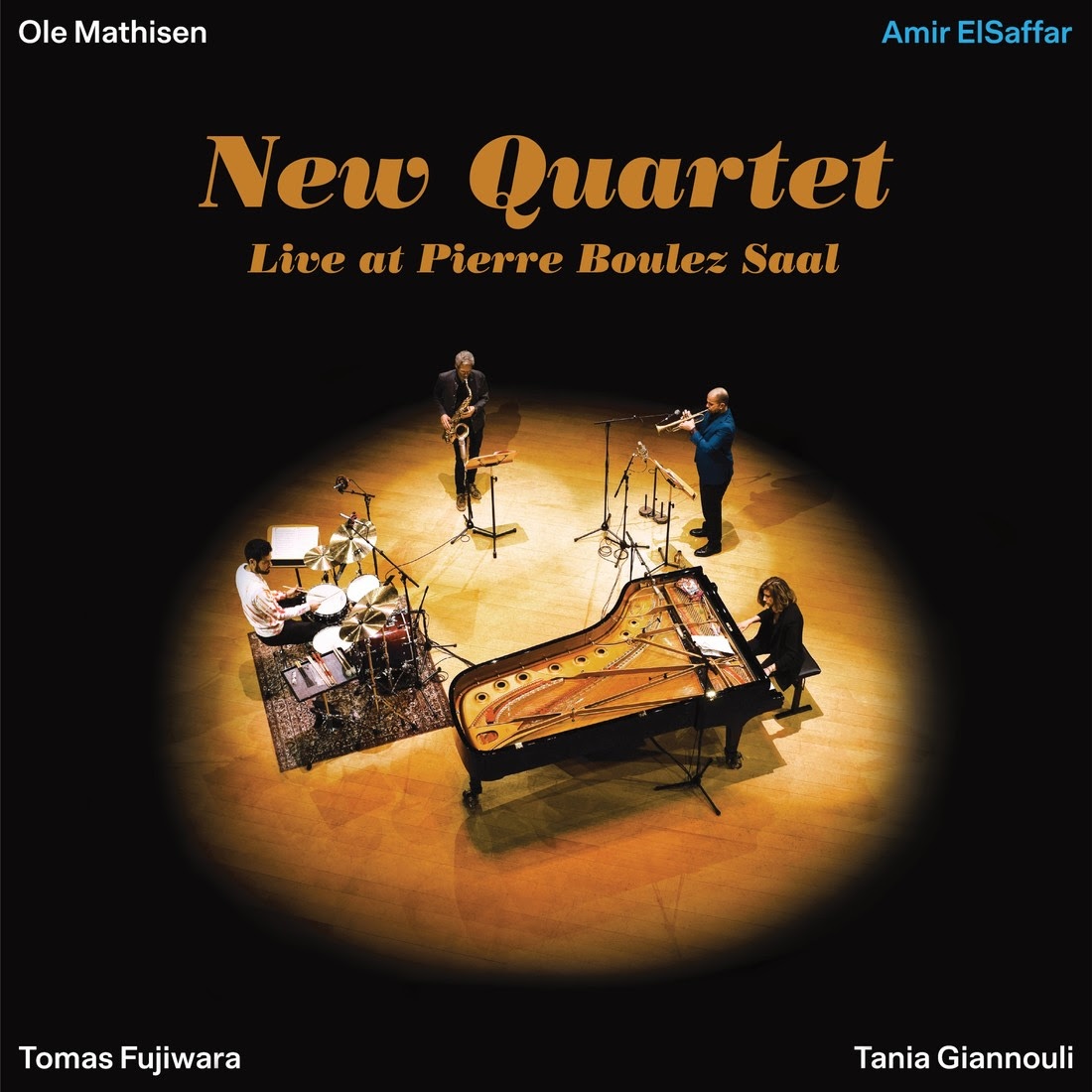

For trumpeter Amir ElSaffar, three such horizon-openers converge in his latest album, New Quartet Live at Pierre Boulez Saal. Recorded at the famed Frank Gehry-designed concert hall, it’s a scintillating performance in which he is joined by Ole Mathisen on saxophone, Tomas Fujiwara on drums and Tania Giannouli on a specially tuned “microtonal” piano, their vibrantly shifting and shimmering musical confluences calling to mind the unclassifiable musical journeys of the late Alice Coltrane.

First came the revelation of his youth, or rather a series of revelations.

“I grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, which is a suburb of Chicago,” he says in a video chat from his home in the Bronx, where he has lived for most of this century. “Most of my musical background was Western classical music, and then jazz, which I found thanks to my father, who was an Iraqi immigrant. But his favorite music was the blues. He’s the one who brought me to the Checkerboard Lounge on the Southside of Chicago when I was very young. Buddy Guy was playing at Buddy’s Legends. B.B. King would come to town. And there was a guy named Vance Kelly, there were a lot of local heroes.”

“My whole world until I graduated from DePaul in 1999 was between classical and jazz, and then playing, gigging around town in rhythm and blues bands and wedding bands and bar mitzvahs and Greek bands and all kinds of stuff. It was probably my most busy time in terms of gigging. I was a musician in Chicago. But it had nothing to do with Arabic music. I didn’t know anything about it.”

That, though, came with the second revelation. His older sister, classical violinist Dena, had become interested in those cultural roots and excitedly shared them with her brother. Moving to New York, he dipped his toe into the experimental jazz scene, but also made his way to Arabic music concerts and workshops. When he won a $10,000 prize in a trumpet competition in 2002, he impulsively bought a ticket to Morocco and from there to Baghdad—much to the horror of family both here and there, as it was just as the U.S. was ramping up for its invasion. Nonetheless, he sought out teachers there, in intensive study of Iraqi maqam, a system of modes found in many countries and cultures from North Africa to Western China, comparable to India’s raga traditions.

“There was one particular piece I had learned in a lesson and then, by chance, I found a random CD and played it, and it was the same piece and I was so moved by different elements,” he says. “One was the blues element in Iraqi maqam, which is this deep-seated suffering and this wail of a cry in it. And the other was the intense intellectual rigor of the structure and the logic in the way the compositions were put together. And it became such an obsession of mine to understand, ‘What is this phrase like this? Who is this singer?’”

He got out just before the bombings started, and the musical and cultural experiences came with him.

“It definitely stopped me in my tracks and made a real left turn in my life, my career,” he says.

The third came after he settled back in Manhattan, getting a gig in avant-garde jazz pioneer pianist Cecil Taylor’s band and engaging in heady explorations with such other cross-cultural young lions as pianist Vijay Iyer and saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa. The crucial moment came one early morning when he had been staying at Taylor’s house.

It was 5:00 a.m. and the sun was coming up,” ElSaffar recounts now, as excited as if it had just been yesterday.

There was a grand piano in the living room, long-neglected. Taylor gave him permission to try it.

“Apparently he didn’t let many people touch his piano,” ElSaffar says. “I’m not a very good piano player. But the piano had sort of de-tuned itself into something very wild and beautiful and rich and otherworldly.”

Skip to today, and you can hear the full flowering of that dawn’s beauty in New Quartet Live at Pierre Boulez Saal. The album opens with a long, drawn-out trumpet note, a foghorn sounding at some mythical confluence of those three locales, a delta where the Chicago River, the Tigris and Euphrates, and the Harlem and Hudson rivers all flow together. It’s a spellbinding session of ElSaffar’s compositions, rooted in melodies and modes from the Iraqi maqam traditions, which like Taylor’s piano includes notes between those of our Western scales., a.k.a. microtones.

For this project, ElSaffar purposefully tuned the piano in a vast array of tones beyond the scale of 12 found in Western music. It’s something he had worked with in the 2000s with works he created with Vijay Iyer. For Athens-born Giannouli—who had never played microtonal piano before but embraced it heartily—he created a tuning that seems to present boundless possibilities of musical hues.

The piece “Ghazalu,” for example, starts with Giannouli creating shimmering constellations of sounds—essentially a microtonal piano sonata—before the others join, with ElSaffar singing Arabic verse (as he often does). It’s both a culmination and distillation of ideas he’s been pursuing, from large-scale works (2024’s equally bracing The Other Shore by his 17-piece Rivers of Sound ensemble featuring a mix of Arabic and western instruments) to traditional Iraqi repertoire (in 2006 he founded the ensemble Safaafir, which also includes his sister, in which he plays the hammered zither santur and has produced and released a new album of maqam performances by master singer Hamid Al-Saadi).

The New Quartet is his first straightforward jazz group lineup.

“I wanted to choose instrumentation that didn’t have some exotic element that could quickly be pinned as, ‘Oh, you’ve got a santoor in the band,’” he says. “So no, we have a piano and a saxophone and drums. And the piano just happens to be retuned and suddenly it opens up a lot of other territories.”

Even that, though, isn’t a great break from jazz tradition, he maintains.

“The bridge to finding how to introduce microtones into harmony was really through Cecil,” he says. “But he’s from the continuum of Monk and Ellington. He was telling me that apparently DownBeat magazine, or as he called it, ‘Beat Down,’ critiqued Ellington’s band for being out of tune. Ellington wrote a letter that was in the following issue saying, ‘No, my band is de-tuned,’ expressing intention behind all that. And you listen to him and those chords are very funky. When people try to reproduce that music today in a very sanitary way, it doesn’t have that quality anymore.”

For this Chicagoan, this is all part of a mission to introduce people to sounds that to them may seem new or different, without making them seem, well, foreign.

“It’s really important to me to bring these musical languages and traditions together in a way that makes sense in the moment,” he says. “You don’t have to have prior knowledge. People really don’t know until you tell them there’s a half-flat, because the ear very quickly adapts to those sounds.”

Leave a comment