Ian Astbury is a true believer. As the singer for the Cult, he’s been immersed in the ritual of rock ‘n roll, of sweeping riffs and full-throated vocals, for four decades. He’s been fueled by a lifetime of art and music, shamanic and indigenous influences, spirituality and mysticism—all of it in service of a night of communion and release with an audience.

“I don’t really have hobbies. I love music,” Astbury says. “Nothing’s really changed since I was a child. I don’t go off on yachts. I don’t go off on vacations. I’ve usually got my nose in something that I’ll bring back to the pot. The muscle memory’s there.

“I mean, you can’t half-ass the Cult. There’s nowhere to hide.”

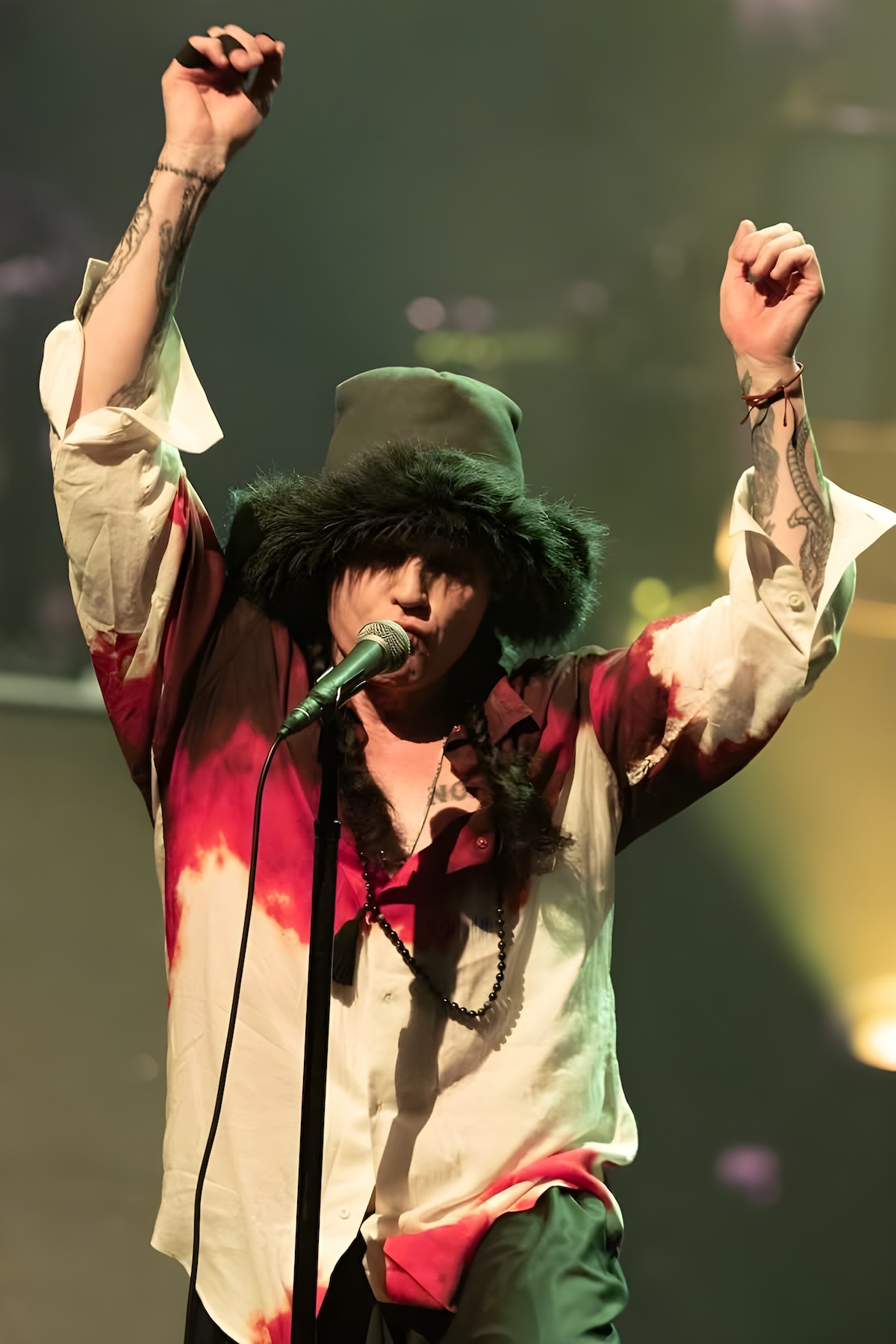

On the band’s current tour of North America, which ends October 30 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, the Cult is digging deep into that history. The night opens with a set performed as Death Cult, an early post-punk, dark wave period for the group that Astbury says brings the Cult an added shot of inspiration.

“We were thrilled by it, and it bled into what we were doing currently with the Cult,” says Astbury. “I wouldn’t say we were reinvigorated, but it definitely put another gear in the Cult. It gave us an edge—an edgy edge. I think we’ve maintained a pretty good edge to the Cult as a live band, but this gave us something else. It gave us a knife and something that nobody else is able to do. It’s authentic.”

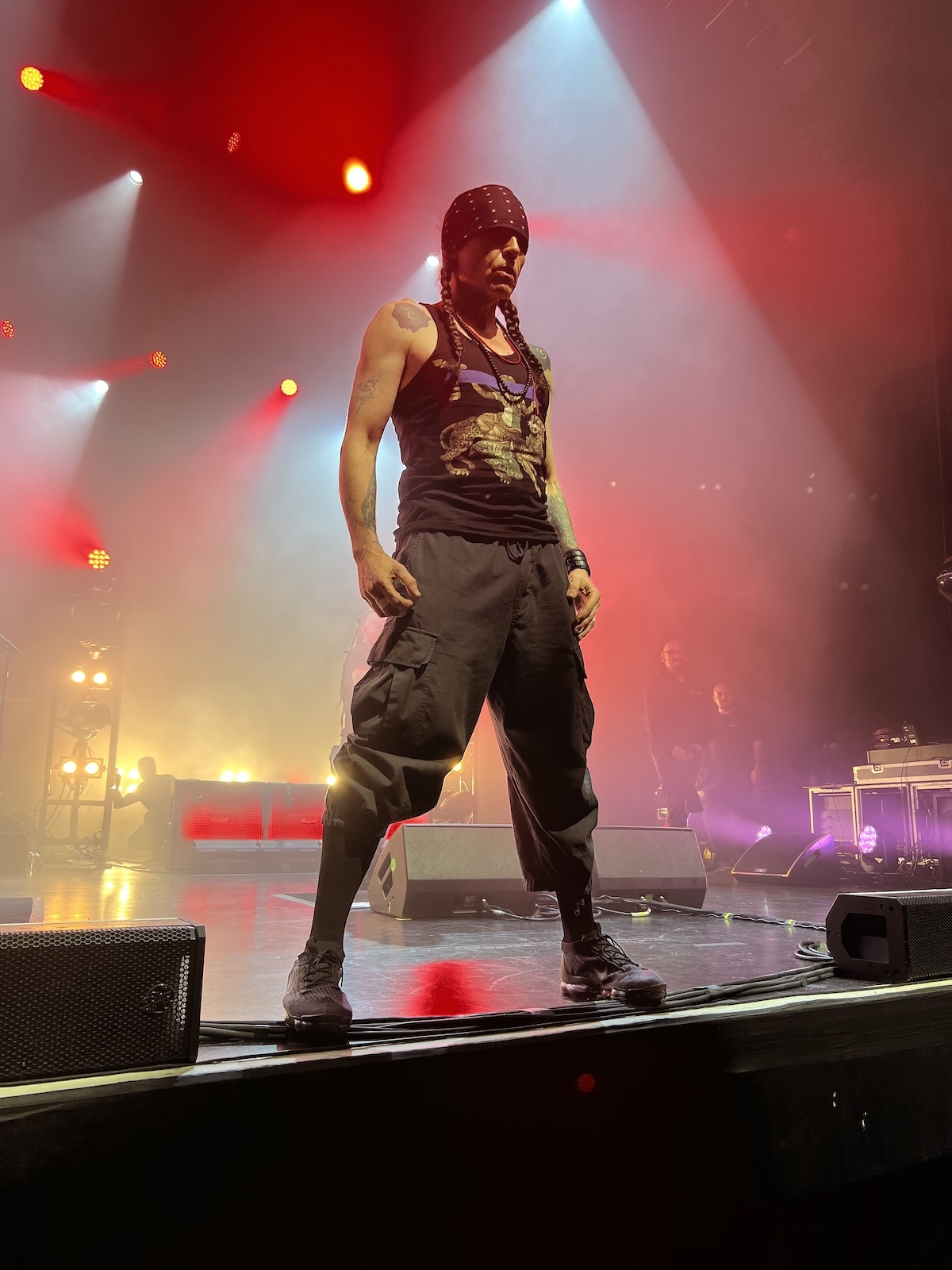

As he speaks, Astbury is at a corner table in a favorite French bistro in Los Angeles, surrounded by Belle Époque-style décor, with ornate mirrors and neat rows of wine bottles along the walls. It’s a quiet weekday afternoon, and he’s got a black doo-rag wrapped around his forehead, black hair knotted on top, skewered with a pencil as a makeshift hair pin.

This bistro has a full menu, but Astbury orders only an oat milk latte. He says he once saw Nick Cave here sitting alone at a table, writing into a notebook. He seemed to be settled in for a while, like it was a private sanctuary in town. Astbury, mostly based in L.A. since the late 1980s, appreciates the space for similar reasons.

The idea of resurrecting the Death Cult name came to Astbury after spending time with those old songs, while also noticing a new generation of artists embracing a similar darkwave sound (Vowws, Cold Cave, Molchat Doma, Twin Tribes, et al.), which he likes to call “gothic futurism.” It felt relevant to the times, and his feelings for a world racing toward a dead end in the 21st Century, which he describes with a grim stream of labels: “Zero point, dystopia, a glitch in the matrix…”

“I became fascinated with that period of music again,” Astbury says. “It just instinctually felt like picking up on a dystopian frequency.”

The idea to actually take the Cult back in that direction came to him one day, and he shared it with the band and its team: “I said, ‘What about doing Death Cult?’ Initially, it was like, ‘What? Really? How? Why?’”

That was in 2023, and with guitarist and creative partner Billy Duffy, the band revived the Death Cult name for live performances, starting with a sold-out show at the 1,600-capacity United Artists Theater (then known as the Theater at the Ace Hotel) in downtown Los Angeles. It was the first Death Cult set since 1983, and the first-ever in America, with a setlist focused mostly on material created before the Cult’s 1985 Love album.

The one-off L.A. show, followed by a short U.K. tour, showed there was a demand, even with the likelihood that for casual fans of the Cult’s hard-rock hit-parade, the name Death Cult would have little meaning. For serious followers familiar with the band’s history, it was an intriguing turn.

“People who like our music are quite discerning,” Astbury notes. “They go away and compare notes.”

For the band—also including drummer John Tempesta and bassist Charlie Jones—reaching back to that time wasn’t a stunt, but a jolt of adrenaline. Astbury compares it to injecting super-charged, platelet-rich plasma back into a human body.

Evidence will be offered on a new 16-track live album as Death Cult, Paradise Live, recorded in Manchester in 2023, and set for release in January.

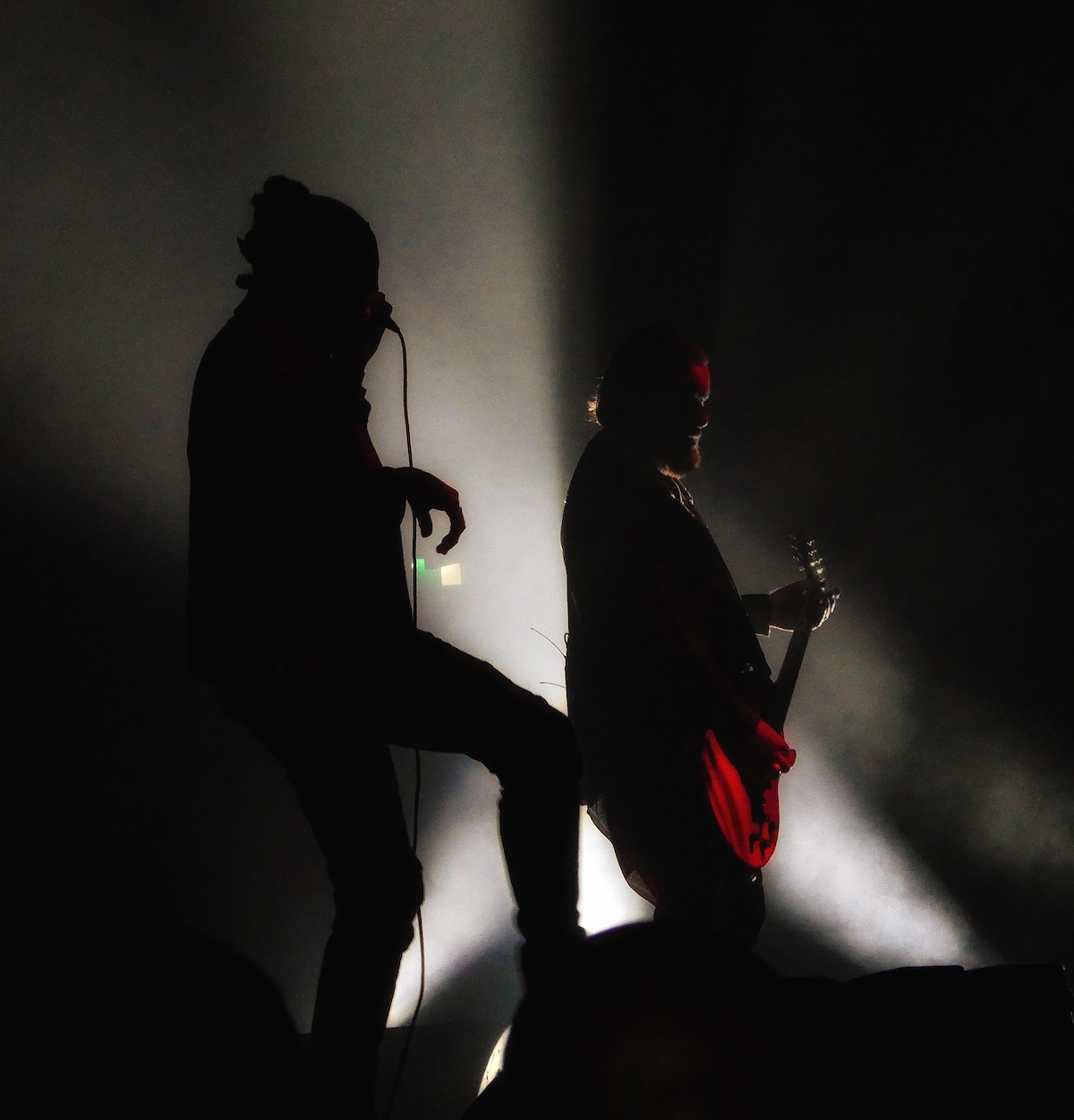

Back in May, Death Cult were onstage at the Cruel World festival in Pasadena, California, during a particularly competitive hour in the misty late afternoon. At different points, their set overlapped with others by Nick Cave, Garbage, and Devo, but their crowd never thinned out, as Astbury and Duffy dove into lesser-known material from the gloomier Death Cult era.

Dressed that day in a long black tunic, and looking again like a holy man leading a spiritual event, Astbury tossed tambourines across the stage with reckless abandon. To his left was Duffy, cradling a white hollow-bodied electric guitar, accompanying the singer on “Hollow Man,” which unfurled with a nervous energy and faster pace than it once did in the 1980s.

The shadowy “Moya” went even further back to Astbury’s time leading the earliest incarnation of the band, Southern Death Cult. Later, to close out the set, came “She Sells Sanctuary,” the signature hit song from the larger Cult songbook. Whether in Cult or Death Cult mode, there was an ease to their combined power onstage.

At the bistro, Astbury explains: “What compels me to do it? I’m a dog, there’s the meat. Let’s go.”

He estimates that he’s performed about 2,000 concerts in his life, mostly with the Cult, but also in his mid-’90s band Holy Barbarians, plus occasionally singing with James Lavelle’s Unkle, and his years stepping into the Jim Morrison position with Doors survivors Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek.

“Add it all together, and that becomes natural instinct,” Astbury says. “That’s pretty much what I operate on. I’m not asking the algorithm for what to do next.”

Several days later, Duffy is back in L.A. from his home in the U.K., and checking in on a video call, bearded in a black T-shirt and shades, framed Cult posters on the wall behind him. He says his partnership with Astbury has survived through popular triumphs and occasional breakdowns in part from “the fundamental desire to do this for life.”

“We were born a year and a day apart,” he adds. “We’re very different and we’re very alike. And in some ways, that’s what’s given us the commonality to keep going with it.”

They split apart a couple of times over the years, including a low point in 2006 and 2007, when both Astbury and Duffy went off into other directions. They always found their way back together. “We do other things,” says Astbury. “We have other creative relationships, which is good. I think it’s really good for that core relationship to sleep around creatively, because you can bring it back.”

As a boy living near Liverpool, Astbury was awakened by his first hit of David Bowie through the 1971 song “Life on Mars,” a soaring, glimmering rock ballad, sung by a Technicolor rock ‘n roller from outer space. It was the first single young Ian ever purchased. “When I heard that, that was my frequency, that was the calling,” Astbury says. He grew up partly in Scotland and England, then emigrated to Canada, before returning to the U.K. as a young man in time to be part of a vibrant music scene erupting again.

As a fan in 1979, he and some friends were waiting outside a venue for a glimpse of the Clash as they walked out. Instead, manager Kosmo Vinyl invited them inside to meet the band. The experience left a mark.

“Sitting with those guys, they made it feel familiar,” recalls Astbury. “So certain artists were accessible—punk. And I just thought that’s the way it should be: No better than, no less than, we’re all at the same table.”

He was barely 20 when he met Duffy, bonding in part over the Sex Pistols. Duffy was a Manchester kid who had been in a band with Morrissey, and pals with future Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr. Duffy found a lasting partner in Astbury.

“We’ve got a lot of cultural similarity,” says Astbury. “There’s an unspoken contract, there’s an alchemy. It’s undeniable. We both sense that. We know that when we convene, something else comes in. The Holy Ghost appears.”

When they got together, it was a time of transition for Astbury, whose band Southern Death Cult was evolving (with the addition of Duffy on guitar) into Death Cult. That version of the band was barely in operation for seven months before things shifted again, this time toward the swelling rock riffs that showed itself on the Love album, beginning their time as a hitmaking operation with “She Sells Sanctuary.”

“The reason why we changed the name from Death Cult to the Cult after about six or seven months was that we thought we were getting pigeonholed as a goth band, and we didn’t feel like a goth band,” says Duffy. “We certainly didn’t want to sing songs about vampires and bats and graveyards and all that.”

Subsequent Cult hits like “Sweet Soul Sister,” “Love Removal Machine,” and “Fire Woman,” were muscular enough to fit easily in the era of Guns N’ Roses, making them a rare band (like Motorhead) that punks and metalheads could agree on. At the time, hair metal dominated MTV and the Sunset Strip. “We were like a little bit of a beacon of hope,” agrees Duffy, with a grin. “We were a spandex-free zone. There were a few bad hair experiments on my part, but all I can say is I was drinking heavily at the time, so I’m not responsible.”

The Cult were recruited to open dates on Bowie’s Glass Spider tour in 1987, facing stadium crowds impatient for the headliner every night. “I remember dropping my pants and Bowie was in stitches,” remembers Astbury, by then already comfortable with large crowds.

Moving around as a child helped create the social skills that would lead to him becoming a supremely confident frontman, delivering hard rock with bravado. “Being an immigrant kid, I had to adapt to environments really quickly,” he says. “So maybe that gave me an edge in terms of knowing how to be in a room, knowing how to be around people. I wouldn’t say it was bravado, it was more a sense of, I was a coyote. I could read a room.”

He could also be outspoken in interviews, or between songs onstage, if the mood struck. It was an impulse he now credits to his early years in Glasgow and Merseyside, England. “We call it being gobby,” he explains. “As a culture, we had to be very quick with wit, because if you weren’t quick witted, violence wasn’t far behind.”

At the beginning of the ’90s, Astbury was one of several rock singers approached for the Jim Morrison role in Oliver Stone’s movie The Doors. (Among the others considered were Michael Hutchence of INXS and the Beastie Boys’ Ad-Rock.) Astbury didn’t make the film, but began a relationship with the surviving Doors that led years later to an invitation to join guitarist Krieger and keyboardist Manzarek on the road as the Doors of the 21st Century.

“Oh, that was a whole lifetime, because I did about 150 shows with them,” Astbury says now of the experience. “It was family because it was very intimate. They were my mentors and my friends. I learned so much from them. I’m in debt.”

Astbury also went into a studio with Krieger and Manzarek to record three songs with producer Ken Scott (Bowie’s Hunky Dory and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars). The tracks were never finished. Astbury calls them “sketches,” and adds, “I have no idea where the tapes are. I didn’t get a cassette. I wasn’t allowed anything. I think it was an inner circle within the inner circle [thing], shall we say.”

Astbury and Duffy reunited in 2007, and the Cult has remained in action ever since.

At the Beacon in New York on October 14, the night began with an eight-song Death Cult set, from a twangy, spooky “Ghost Dance” to a thunderous “Spiritwalker.” The opening set isn’t limited to songs from the 1983 self-titled Death Cult EP, and includes others written during the same period but released later under the Cult name. After an intermission and a film, the band returns for a traditional Cult set of ferocious hits.

“We do give it our best, honestly,” says Duffy. “We don’t phone it in, and I know some do. It’s a real deal, warts and all. And like any real band, some nights are better than others. We’re an organic creature.”

The Cult’s last studio album in 2022 was Under the Midnight Sun, which was midway into production when the COVID pandemic landed, and shut everything down. It was a collection of songs built from the same epic rock elements the band is known for. Work on a follow-up is unlikely to begin until next year, Astbury says.

“I’m sure Billy’s got something somewhere. I’m always noodling. We’ve got a piano in the middle of our house,” Atsbury says regarding new material. “In the ether, there’s music, lyrics, ideas. If it happens, it’ll happen organically.”

While there is no formal plan yet to go into a studio, the idea of returning to the Death Cult way of doing things for the next recording is appealing to Astbury.

“For the first demo made for Death Cult, we had one hour—record it, mix it, and done in the hour,” Astbury remembers with a smile. “I’d like to do something like that, just walk in, maybe do something in a week. What could you do in a week? That’d be really interesting.”

Leave a comment