Westerns feel good, feel right, in volatile, contested times. But not just any Westerns — not kitsch dross like Joel Souza’s Rust, which even a real-life blood curse can’t make matter. No: we’re talking feral sagas of de-civilization which burn like a dirty-ass Book of Job, scorched to the bone with Job’s question, “Why did I not die at birth?” American Primeval tried, but it descended into mawkish tearjerker.

Perhaps the motherland of the frontier genre — America — has grown, culturally speaking, too kitschy, too sappy, too soft to be the parent that this genre needs. And maybe our cultural degeneration set in way back, once the closing credits rolled on John Ford’s vicious 1956 masterwork, The Searchers.

In the splintering ’60s, essential Westerns weren’t even made in America and they weren’t made by Americans. A Fistful of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More, The Good The Bad and The Ugly, Once Upon A Time in the West — these salty strolls on the precipice (“get three coffins ready”) were shot in Spain by an Italian: Sergio Leone.

And now? Now that frontier consciousness and manifest destiny are back bigtime as the world reverts, who’s blazing the accompanying cinematic trail — who’s sitting in the director’s chair?

Adilkhan Yerzhanov is. He’s a razor-sharp moviemaker born in the early ’80s in a copper-mining region of extreme cold and heat in the center of the then Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic — now Kazakhstan. Yerzhanov, now in his early 40s, shoots wild, black-humored, sometimes brutal but always striking cinema on the vast steppes of his Central Asian homeland, bordered as it is to the east by Xinjiang (China’s own Wild West) to the north and west by Russia (Europe’s revanchist Black Hat power), and to the south by the restive republics of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

His latest, last year’s Steppenwolf, so far screened mainly at festivals and circulating on Blu-Ray, brings an artist’s eye to the neo-Western. In fact, the opening shot of a handcuffed man standing on the steppes with a bag over his head brings to mind René Magritte’s 1928 Lovers series — paintings many believe inspired by Magritte witnessing as a boy his mother’s corpse being retrieved from a river, with her saturated nightgown having risen up to wrap her face.

All faces are unseeable in Steppenwolf’s opening scene, the camera rolling on over police riot shields being washed of blood by troopers we never get a square look at until the hooded prisoner makes his way past them and to a bus, finishing a cigarette and boarding under guard by a gunman rendered human in outline only — his form void-black from boots to ski mask. This is a world in which the individual faces annihilation.

“I love Magritte and this is an homage to his work,” Yerzhanov tells me. “The mysterious world of Magritte, his kind of magical realism, that’s what my film is about. A mixture of truth and absurdity. Reality and phantasmagoria.”

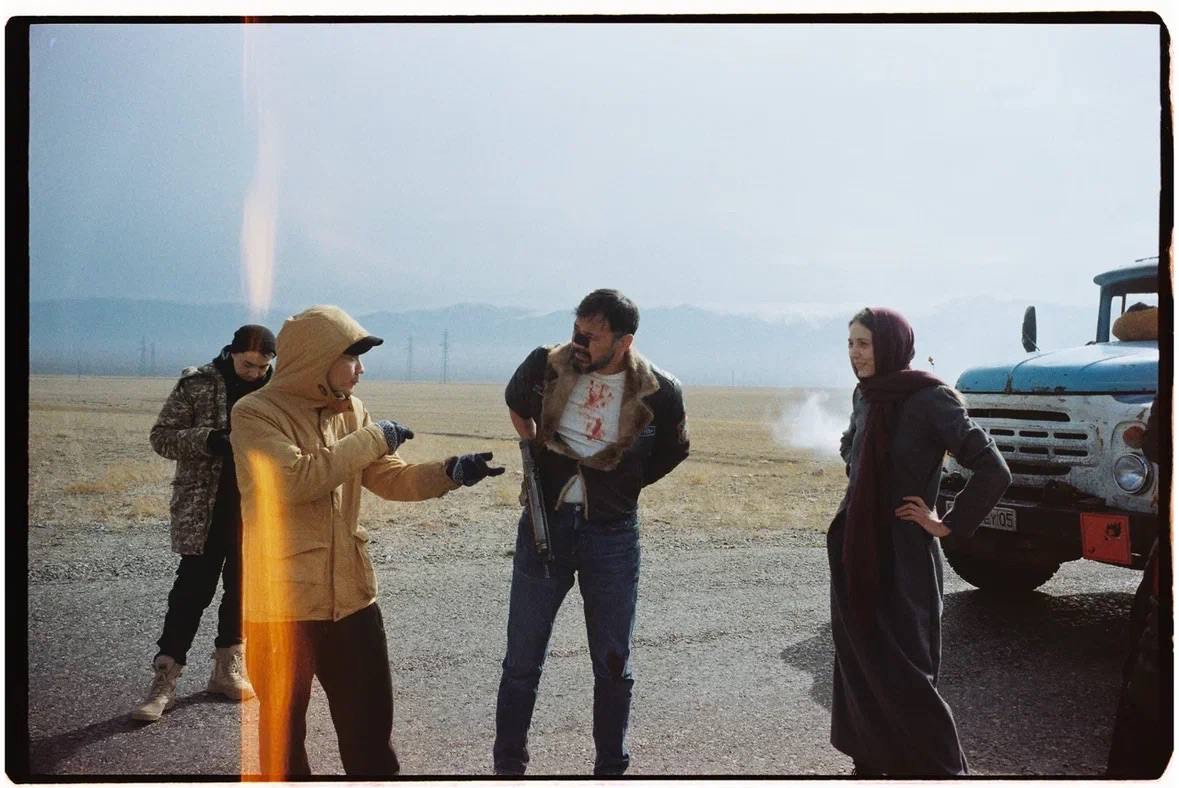

This story of a mother, Tamara (Anna Starchenko), searching for her snatched son with the mercenary help of a vendetta-focused brute, Brajyuk (Berik Aitzhanov), remains grittily grounded by the visceral nature not just of the film’s unrelenting violence but its rich, tangible textures of faces, hands, sand — and by the almost tender if fleeting depiction of people existing in collective isolation, scattered here and there in a broken desert society.

Just like a classic Western! — but with modern rifles and machinery. It fits, says Yerzhanov, even if his countryfolk are yet to fully grasp it.

“The Western genre is not popular at all in Kazakhstan and much more comedies are filmed, but for me, our culture has a lot in common with Westerns: our landscapes; our past as nomads. We are those same cowboys, even more than the Americans,” he says.

Adilkhan grew up during the collapse of the Soviet Union and the chaotic years that followed in its former constituent republics. “You see, we had the ’90s, and those were the real times of the Wild West — a ruined society, no law, banditry and poverty. Now we are one of the richest societies in the region, everything is much better. But I remember those times. I lived then and these realities of the Western genre are not just a movie. This is my childhood and youth. I remember when a person relied only on his family and his life. No law, only you and chance.”

A blot on Kazakhstan’s recent record is Bloody January, a 2022 spasm of civil unrest in which state security forces killed more than 200 protestors and arrested thousands. “Terrible days,” says Yerzhanov. “Everyone was afraid to leave the house.”

While the domestic situation has since cooled off — “for me we are the freest in the region right now” — Adilkhan sees the world devolving overall. “It seems democracy has gone down the drain. An authoritarian style of government is forming around us and all over the world,” he says. “Something terrible is happening. Everything is upside down.”

Hence grim nomadic sagas have come back into their own. “Now the whole world is a big Wild West. Whoever has a bigger Colt feels right in world geopolitics. It’s sad. That’s why the Western has become even more relevant.”

Leave a comment