Prior to meeting Mat Osman of Suede some three decades ago, I had already heard many positive things about him from colleagues who’d interviewed the bassist. We crossed paths on February 2, 1995, after Suede’s landmark show at the American Legion Hall in Los Angeles. He was approachable, warm, and inclusive. I gave him a lift to where Suede were staying, and he invited me to their afterparty—thoroughly PG-13, nothing remotely inappropriate. When I recount this experience during our recent interview for Suede’s new album, Antidepressants, he worried I might reveal otherwise. Far from it.

Osman remains one of Suede’s pillars. He co-founded the band with vocalist Brett Anderson, their friendship stretching back to their teens. Suede were, arguably, the spark that lit Britpop. Ricky Gervais briefly managed them, the Smiths’ Mike Joyce sat in on drums, and Elastica’s Justine Frischmann—famously Anderson’s partner before leaving him for Blur’s Damon Albarn—was their guitarist.

More from Spin:

- Nine Inch Nails Come ‘Alive’ In Video For ‘TRON: Ares’ Track

- Brandi Carlile Enlists Aaron Dessner, Justin Vernon For New LP

- Perfect Vision

Once the proper lineup fell into place with Simon Gilbert on drums and Bernard Butler on guitar, Suede won the Mercury Prize for their 1993 self-titled debut. After Butler’s departure, they brought in Richard Oakes and added Gilbert’s cousin, keyboardist Neil Codling. That lineup earned another Mercury Prize nomination for Coming Up (1996).

Suede split in 2003, reunited in 2010, and have released strong records ever since. “The band splitting up is like the first time you get your heart broken,” Osman says from his home studio. “When we came back, we were really clear that we would never let ourselves get into a comfort zone or switch off again, and we don’t do huge tours anymore.”

This space is brightly lit from its skylights. The back wall shelves are lined with records on one side and books on the other—including copies of Osman’s own novels: The Ruins and The Ghost Theatre, as well as the nonfiction art title, England on Fire, co-written with Stephen Ellcock. I assume his brother Richard Osman’s bestselling The Thursday Night Murder Club is in this collection, and predict Netflix’s star-studded film adaptation will dominate the streamer’s charts upon release.

“Music is an extraordinary thing to do with your life,” says Osman. “It’s a privilege. It’s magical. Because the band ended at one point, I know every gig could be the last. I know how fragile people in bands are. We’re never going to let this become ordinary again.”

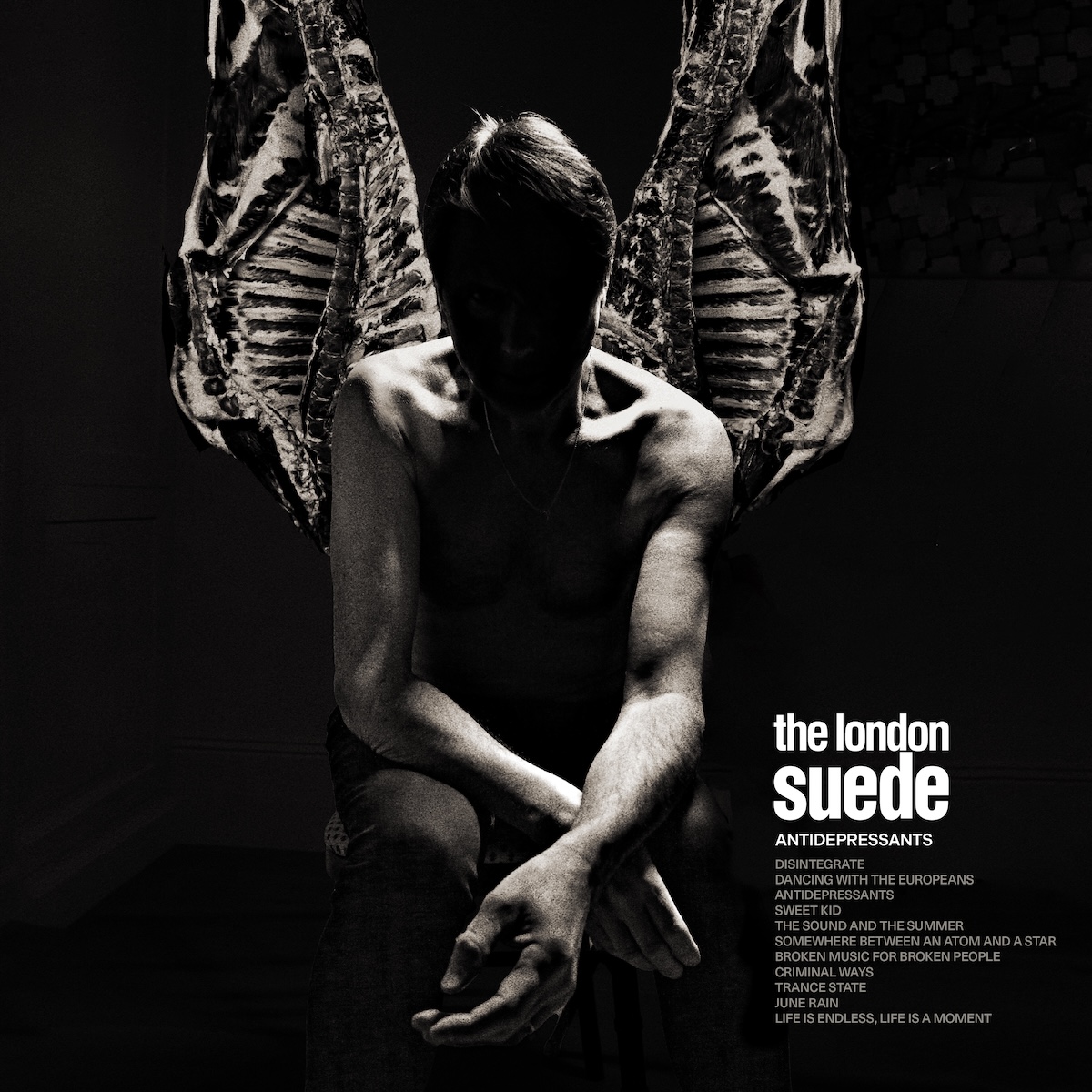

Antidepressants is anything but ordinary. Produced by Suede’s longtime collaborator Ed Buller, it bristles with post-punk energy, grounded by Anderson’s candid, unsparing lyrics. It recalls the self-medicating themes of Suede and his trademark, unfiltered observations—no less dark in middle age. The album is guaranteed to resonate with Suede’s global cult of fans. To celebrate the release, the group will stage a “Suede Takeover” at London’s Southbank Centre, performing across venues from September 13 to 19.

What Suede are not planning is another North American tour. Their co-headlining run with the Manic Street Preachers in 2022 was their first in 25 years, apart from a lone Coachella set in 2011. Yet in 2018, Anderson flatly told me Suede would never come back to the U.S—and then they did. So hope springs eternal.

The band members often disagree with me in interviews, which is both intimidating and invigorating. Osman, the gentleman and creative scholar that he is, leaves me with a cautious but telling sendoff: “Never say never.”

Artists from the ’90s are having such a moment right now, aren’t they?

I feel weirdly disconnected from most of that. Partly because we’re trying as hard as we can to be un-nostalgic, not to lean back on stuff we’ve done before, not to rely on it. There has been a sense of momentum with us for the past five years which is very forward looking. It’s a bit strange to suddenly be lumped in with this ’90s summer. But I agree, one of the things that has been key to the summer in Britain is the live shows. The Oasis live shows, the Pulp live shows, and the sense of community and abandon that come with those things.

The interesting thing that’s happening with artists from that time is you’re having the best decade of your lives career-wise, but it’s not dependent on each other or a scene. Everybody is doing exactly what they want to do with the benefit of experience, and the added benefit of not doing it for chart placement, yet Suede are still in the UK Top 10.

It’s so true. It’s really hard to appreciate what it was like in the mid-’90s, in London specifically. It was very competitive with everyone fighting out against each other for chart positions and pretension, very combative. You were rewarded if you were acerbic about other bands. A whole load of young people were making money for the first time in their lives, and a whole load of record companies were too. Suddenly, this boom is going on. It was this weirdly Thatcherite capitalist time. It was all about making it big.

The funny thing is, when that falls away and you’re not on front covers and you’re not in the tabloids, there’s a moment of horror. The next people have come along and taken your place. Then you’re left with: “What are we doing this for?” For Suede, we went back to how we started, and then, how we started again with Richard. That sense of what it’s like for the five of you to be writing songs and playing them and no one else is there. Trying to make each other excited, trying to capture that energy and that drive.

It feels like that transferred to your audience. Speaking for myself, I am excited and energized by what you’re doing, both in the studio and live.

What happens in that time is, the divide between you and the audience disappears a little bit. In the ’90s, the gigs could be really combative. It was all about, “Look, we’re up here, fucking massive. You’re looking at us.” There were loads of people who came to the gigs who hated us. The gigs nowadays are much more celebratory. People turn up at the gigs at 9 in the morning, and queue up before the fucking staff are there. They have these events they do together. I’m not sure this sense of celebration was there before. It doesn’t feel like us trying to impose something on people anymore, which I think we tried to do. It was like, “Fuck you. This is our show. You better enjoy it.” Now, there’s no great gig without a great audience.

As a Suede audience member for over 30 years, every show has been like a religious experience and really stayed with me. I remember every gig distinctly. You really put on a show. You give us a lot.

I’ve never understood people who don’t want to put on a show. I absolutely love it. Of all the bands I know that have come back and started again, it’s that live feeling, the electricity between you and the crowd, that’s what you really miss. People always compare it to drugs or sex. But it’s not because it’s something much more communal. It’s a willed hallucination between you and the audience. You get to behave in a way that you would never do at the school gates or in the shops or anything like that. You expect the crowd to give that to you. I love it. When I see people sweating, I love it. When I see people crying, I love it. When I see people on each other’s shoulders, that’s a flow of energy. It’s not us doing it to them. It’s been said a million times, but the best gigs are 5,000 in the audience and five on stage. That’s just the way it works. It’s not particularly complicated. It’s an incredible feeling.

Do you feel Suede is hitting its stride now?

Brett always says the problem is that when you come back, you start off with a victory lap. But you can only do one victory lap. You can’t repeat that. I often see decreasing returns for the same thing. When we came back, it was with a real sense of something to prove. We’ve made a couple of not very good records, and we felt the memory of the band was quite tarnished. You’re remembered by how you fuck up rather than how you do well. We had much more of a desire to do something good than most returning bands. There was a real hunger in us to rewrite history. Forget that last record. This is what we should have done after Coming Up. Let’s go back and see where we went wrong. It’s like one of those alternate histories.

When we did the best of album, one of the things we did was come at it with fans’ ears. We listened to those first records to put together the best stuff. It was so much easier to see it not being in the eye of the storm, to be past it and suddenly it’s like, “Why the fuck are we trying to do this and this and this when we do this really well? Let’s try and do that again.” It sounds so simple, but it really isn’t. It’s quite hard to see yourself in that light.

One of the things I find with so many reformed bands is the records they make are souvenirs. It’s merchandise, like a T-shirt or something. You make a new record because you think you ought to. You put the first 12 songs on that you wrote, and they’re not as good as the things you’ve done before. Then you wonder why five years down the line, fewer people are coming to see you. We were always really driven to make better records than we’ve made before.

That’s a tall order.

It’s really hard work. This is something we never would have admitted back in the ’90s, because it was supposed to come easy. We work really hard on it. We normally write about 50 songs for each record, and lots of them are really good, but what happens is, you look at them, and you go, “Have we done this before?” Yeah. “Have we done this before better?” Yeah. And then it goes. You’re constantly looking for these little places whereby it feels new, but it feels like Suede. Those little spaces become smaller and smaller each time. The lovely thing about your first decade is everything’s fresh. When you go to the studio to do your first record, you do your first proper ballad, you do your first long song, you do your first song with one chord, all of these things, they’re waiting there for you to claim them. Once you’ve written 200 songs, finding something new is really hard. Finding a new space, a new sound for the band, without being gimmicky is really hard. We’re always searching for it. We rehearse and play a lot together, and every now and then, your ears prick it up, and you’re like, “Okay, this is new. This is something we haven’t done,” or, “We haven’t done well before.” Those are the moments you have to keep hold of and make work.

Do you approach making music with the mentality that you’re doing it for yourselves?

The exact opposite. I hear it so much, people saying, “We make it for ourselves, and if other people like it, it’s a bonus.” We make music to move people, to affect people. That’s the whole point of it. It’s like drugging people. You want to change people’s emotional state. You want to make people feel something, make people laugh, make people cry. As I get older, that becomes almost the entire point of doing this. This record wasn’t just made for ourselves. When we started touring Autofiction and “She Still Leads Me On” came out, it was one of those songs that hit a whole group of people. There were so many people coming to me and saying, “That song’s about my mother,” or “That song’s about my girlfriend,” or “That song means something to me. It’s done something to me.” That’s what I want to be doing. That’s the point of spending 30 years doing this.

Doing that tour and meeting people informed this record. It wasn’t made just for us. It was made for the people out there and what they get from Suede and what we mean to them. I have a guaranteed way of knowing how well a song is doing by how many people have it tattooed on them. We started seeing “She Still Leads Me On” tattoos a week after it came out. That’s what this is about. Every time someone says to me, “We got married to ‘The Wild Ones,’” or “We played ‘Life Is Golden’ at my dad’s funeral,” that idea that you’re part of people’s lives, that you’re entwined with how they feel, that seems to be this thing that I want. I don’t like to look at it too closely, because I’m sure it’s a psychological flaw to want to be part of strangers’ lives. But as we go on, it becomes more and more important to me.

When you start a band, it’s for excitement and for girls and for revenge. Spite is a huge driver for careers. But, we’re in our 50s now, and it’s important to me that what we do has some worth. Not just to us, but to other people.

Has it always been this way for Suede?

I always said you shouldn’t listen to what other people think. And it was years later, when we reformed, I was suddenly like, “Why shouldn’t you?” It’s like saying if I have a conversation with someone, I should say all the things that I care about and not care what they think about. That’s not what we’re on the planet to do. We’re here to talk and fall in love and make friends. We’re here to connect. That’s the whole point of it.

The album is post-punk, which would have made sense had it been your first album since that was the sound of the era, but then I don’t think Suede would have done as well had you entered the zeitgeist with it. Why come to this sound now?

This is very much Richard’s record. He’s a really gifted musician. In a way, it was almost a problem, because when he joined the band, he was really young, and me and Brett said, “These are the records that we love,” and we played him Scott Walker, Bowie, Pet Shop Boys, Kate Bush, and all these things and said, “This is where Suede comes from.” He was very much into punk and post-punk. But because he’s a brilliant musician, he took all that stuff on board and wrote Coming Up.

Gradually, since we’ve come back, he’s taken over with his own tastes a lot more, especially with this record and with Autofiction. And the thing is, the stuff that me and Brett were growing up with and loved: the Cure, the Bunnymen, Public Image, people like that, was the stuff that [Richard] loved that his dad got him into. He’s 10 years younger than us. He wasn’t around when these records came out. The music he’s written feels very fresh for Suede. It’s written with a deep love for people like John McGeoch and players of those times. He literally took this record by the scruff of the neck and there’s so much good stuff. I don’t think we’ve ever done anything that sounds that way.

The result is fresh and energetic.

What I think is really interesting is, it’s quite scruffy, youthful sounding music, but Brett hasn’t tried in any way to match the lyrics to that. Brett is determined to write as the 50-something man he is, and to write about the kind of things that rock ‘n roll, and especially the kind of music that Richard is writing, isn’t supposed to be about: marriage, kids, growing old, the terrors of the modern world. That weird dichotomy is what’s interesting about it. If Brett was to try and write from the viewpoint of his 20-year-old self, it would be a period piece in a way. But that music tied with these deep dives into the horrors of middle age goes somewhere really interesting. I don’t think I’m hearing anyone else doing it. I hear people who do some of the lyrical stuff. I hear people who do some of the musical stuff. But I’m not hearing it together.

Why did you decide to record the album live?

I feel like we’re getting better at capturing the live side, the spontaneous side, and the chemistry of the band. There’s something about going into the studio that flattens everything you do. With Autofiction, it was the first time I felt we captured something of the spirit of the band, the youthful spirit. It was this weird snowball thing. We made that record. We weren’t going to make another record like it. But then we toured it, and because it was made live, it was fantastic for live. The shows were so great. They were so life-affirming that it was like, “Let’s make a record that does that more.” Do you remember that Spacemen 3 slogan [album]: ”Taking drugs to make music for people to take drugs to?” It’s like playing shows to learn music that we can play shows with. There was this snowball effect of finally capturing something I don’t think we’ve captured before.

How come you recorded in so many different studios?

What’s happened now, that never used to happen is, we tend to record an album, and at the end of it we find stuff we need. It never used to happen that way. It used to be, “We’re doing these 14 songs, or these 12 songs and that’ll be the album.” Now what happens is, we’ll record 10 songs, and we’re always like, “Okay, these six are an album. They really work. We have to go away and write some more.” So it gets done in bits. Brett’s really obsessive about the album, how it hangs together, how the songs play off each other, what the journey is, what’s missing, and what’s not. He constantly sends out these revised tracklists to the rest of the band. It’s got to the point that everyone just goes, “Look, no one cares about this. You do. I can’t listen to the 14th tracklisting and work out whether it’s better than number seven or whatever. The only reason is, we kept writing new stuff that we thought was better than what we got before.

What can audiences expect during the Suede Takeover?

This is the first time with a big orchestra. We’ve done bits and pieces every now and then. We did Dog Man Star with string quartets. But this is a proper orchestra. All the songs have been scored. They’ve got woodwinds and all that shit. We’re pretty fancy now. The acoustic show we’re doing, a lot of it is going to be actually acoustic, no mics, Brett singing into the room. Nowadays, we’re always trying to break down the barrier between band and audience. As I get older, I’m more interested in no barriers at the front. One of the things I can’t stand about festivals is photographers and VIPs at the front. They’re the last fucking people you want at the front. It drives me absolutely up the wall. We’re going to do a show so we can see the whites in their eyes. The acoustic thing, we’re going to try and do some stuff totally off-mic. You never hear unamplified singing. I was at an opera a couple of years ago, and they walked down the aisle singing, and I suddenly realized, “Is that the first time I’ve heard someone just singing in your head?” It’s so moving and it’s so fragile, and it’s a tightrope walk. The connection is so real. That’s what we’re going to try and do.

You’re giving me major FOMO.

We’ve rehearsed 70 songs.

Are you trying to rub it in?

I think it’s going to be pretty special. We wanted to do an anti-nostalgia thing. We saw a whole load of people doing the same set every night for 100 nights. We thought, “What’s the absolute opposite of that?” It’s all new. It’s all rearranged. Me and Brett are playing a song we wrote when we were probably teenagers, and then there’ll be stuff from this year. It’s wide ranging.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

Leave a comment