Somewhere deep in the archives of the lime-green, forum-shaped headquarters of Mutato Muzika, Mark Mothersbaugh is digging up the distant past.

The building houses his music production company on the Sunset Strip, but also the entire recorded history of Devo, the groundbreaking art-punk new wave band he co-founded with Jerry Casale back in the 1970s. He soon emerges with a box holding a multitrack tape from the band’s revolutionary 1978 debut album, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!

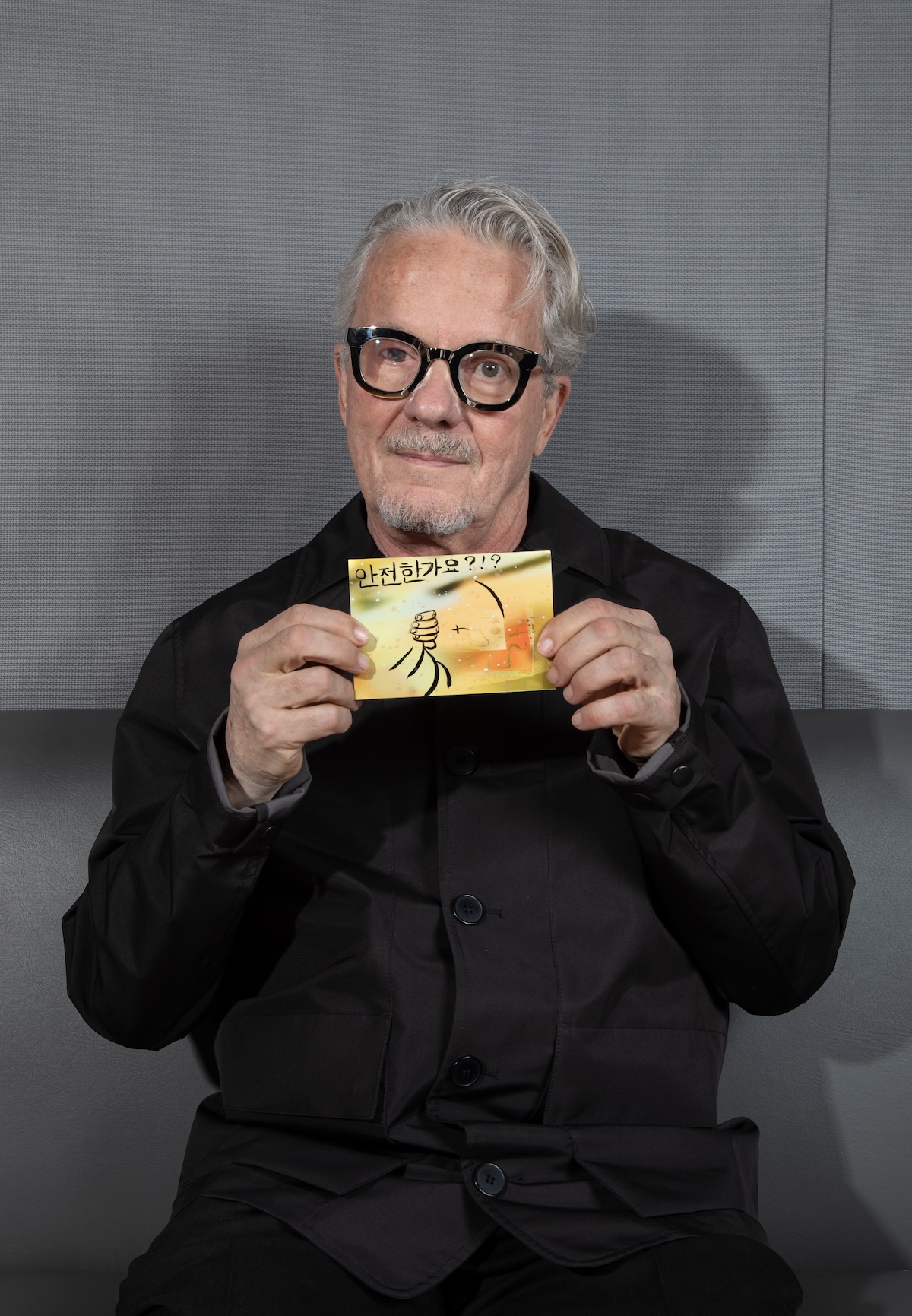

“So this is one of the two 24-track masters from Germany when we recorded with Eno and Bowie,” Mothersbaugh says with a smile, as he sits back down. He opens the box and flips through sheets of paper that list different elements on the tracks, and notes of the album’s acclaimed producer, “I was looking at how nice Brian Eno’s handwriting was.”

Mothersbaugh, 75, is dressed in a black T-shirt with a classic band logo, with shiny metal glasses, short gray hair with a stylish wave on top. He’s here with younger brother, Bob, 73, dressed in plaid; and Casale, 77, in a black jacket.

They are gathered at Mutato Muzika to talk about the new feature documentary, Devo, currently on Netflix. The Devo members admit they can’t look at the film objectively, and they seem ambivalent about the results, but they’ve supported the doc in full, appearing together at festivals and special screenings. Mothersbaugh has shown the film for friends at his Los Angeles home. And the band is releasing a soundtrack album, Energy Dome Frequencies: Songs from the DEVO Documentary.

In truth, Devo is a fascinating encapsulation of what led to this band being created and its ongoing legacy, which inevitably leans toward the earliest years and first few albums on Warner Bros. Records. They weren’t always embraced by radio or the mainstream music industry, but made history. The first hour of this 90-minute documentary is focused on the Devo creation story, followed immediately by the disorienting success of the single “Whip It.”

“You get to find out finally what our creative inspirations were, where the ideas were coming from … from outside of pop music entirely,” says Casale. “It was important for people to understand that there was some intentional substance behind it all. There was some big meta view of the world. De-evolution wasn’t just a smart student pose.

“And now here we are where it’s more than real. We’re living in what we talked about and worse. It’s idiocracy, our worst fears came true. What we were warning about, like canaries in the coal mine, it all happened.”

This is not the story of a rock band desperate to be loved. Devo was anti-rock, anti-cool, a multimedia sendup of conformity, technology, religion, and sex, depicting humankind as a laughable specimen in a Petri dish. Society was lost in consumption and decay, Devo warned. It can’t be stopped, so enjoy! The band would eventually claim a private corner of the festering ’70s punk/new wave movement, touching a raw, awkward nerve with music and short films that mixed crackpot science with aggression and wit.

The documentary tells an entertaining and meticulously constructed story through startling vintage footage and montages colliding the band’s diverse influences. “They definitely looked at the world through their own lens,” says director Chris Smith, known for American Movie and Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, in a phone interview. “Everything they did gets better with time. If social media had been around in their era, they would’ve been one of the most popular bands in the world because they were creating stuff that was so distinctive and visually arresting.”

Devo also remains very much an active band, and have been since before their last album, 2010’s Something for Everybody. On Sept. 24, Devo begins a co-headlining tour with the B-52’s, another demented musical sendup of pop culture born in the ’70s that seemed insane in the time of Styx and the Eagles.

“Nobody can believe that somehow we didn’t cross paths and tour together,” says Casale. “Now we’re probably two of the only bands from that era that can still get on stage and really do it.”

It began in Akron, Ohio, where Casale and Mothersbaugh and their brothers grew up absorbing an endless supply of pop culture kitsch, B-movies and TV commercials, comic books, and cocktail napkin cartoons. Also reaching their ears were the crazy new sounds of ’60s rock, scary Cold War rhetoric and the fiery sermons of local televangelists Rex Humbard and the Rev. Ernest Angley, who claimed the healing powers of Christ himself (“I know there are some of you here who could make a $1,000 covenant! Don’t be afraid! God will stand by you!”).

At Kent State University, Casale and Mothersbaugh met as art students. Mothersbaugh was printing up decals and stickers of strange cartoons that he was putting up around campus. One of them was of an astronaut holding a potato on the Moon. Casale introduced himself and asked, “What do potatoes mean to you?”

They both saw something intriguing in the other, Akron homeboys and kindred spirits, each a provocateur, a collaborator.

The year was 1970, and things were about to take a grim turn at Kent State. Casale was an active anti-war demonstrator. And on May 4 tensions were high: President Nixon had expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia, and protesters responded by torching the ROTC building. Bob Mothersbaugh, then a high school kid, was there for that, and brought an American flag that someone ignited and tossed into the pyre.

So the governor sent a detachment of Ohio National Guardsmen in gas masks to the campus. Soldiers were predictably taunted by activists as tear gas canisters were launched into the crowd. Students scattered, Casale among them. Then, at 12:24 p.m., he turned to see guardsmen kneeling and taking aim. At least 61 shots were fired. Four students lay dead, nine others were wounded.

“We didn’t expect what was about to happen. That was a set up,” Casale remembers. “We were the idiots that were completely chumped because nobody knew what the plan would be. We just thought we were going to do speeches and vent the anger and the outrage, and that would be that. But the National Guard had a big plan, with the governor of Ohio, and they surrounded us. And they had live ammunition.

“I was right in the line of fire, but they didn’t kill the people closest to them. They killed the people behind us.”

Casale personally knew two of the students killed that day. And something inside him changed.

“Like the Matrix, it was a big red pill moment,” Casale says. “Until then, you were probably just a live-and-let-live hippie-ish person that thinks, ‘Oh, America is exceptional, and there’s just some bad apples in the barrel, and it can be fixed.’ And then you find out everything’s been a lie, and you recalibrate. And then you watch history being written when you were there, and you know what happened. And nobody was telling the truth.”

Casale and Mothersbaugh escaped to the basements of Akron, where they began piecing together a new sound and a half-serious/half-comic philosophy about something called “de-evolution.” They recruited brothers Bob Mothersbaugh (“Bob 1”) and Bob Casale (“Bob 2”) on guitars; Jim Mothersbaugh also briefly joined on drums, later replaced by Alan Myers. What emerged from those early experiments wasn’t punk, not yet, but something closer to the skewed blooze of Captain Beefheart, raw groovy stuff for weirdos, with abstract synthesizer sounds from the fingers of Mark Mothersbaugh.

They initially thought of themselves more as performance artists than as a band.

“We had been influenced by a lot of the art movements in the ’20s in Europe,” says Mothersbaugh. “We thought, ‘Well, what’s the 1970 version of the 1920s futurists?’ Although we didn’t agree with their politics, I love their ideas about music. We talked about a cabaret, maybe instead of being a regular band going on tour.”

Casale and Mothersbaugh would travel to Los Angeles to meet with their old Kent State pal Joe Walsh, now a big-time rock star known for chunky FM radio riffs. The Devo boys knew him in his days leading the James Gang in front of ecstatic students soaring on acid and Quaaludes through Walsh’s nightly jam sessions in town.

So in 1974 they drove out to Los Angeles from Ohio in Casale’s Dodge Dart to play Walsh their six-song demo tape. Walsh had a place amid the woods of Topanga Canyon. What he heard was raw and weird, unpolished crackpot blues and synthesizer windouts, starting with a song called “A Plan for U.” Looking back, Mothersbaugh can still recite the lyrics: “Weave to the left, bob to the right / Or you’ll get a flat tire on the freeway of life.”

As the music played, Walsh sat there with a joint in his hand, nodding his head, then got up and stepped just outside of the room. Mothersbaugh looked around the corner and saw Walsh with another long-haired musician. “They’re passing a joint back and forth, stifling their laughter,” he recalls. “He came back in the room after it was over, and he goes, ‘Well, I don’t know if that went over me or under me or around me, but keep up the good work and when you get something new, let me hear it.’”

Their first trip to Los Angeles hadn’t worked out as planned. “We really thought we were driving out to California to get a record deal,” says Mothersbaugh, “and that Joe Walsh was going to hear this and he was going to lose his mind.”

“And he did,” says Casale.

Music was still just one side to the Devo re-education plan. In 1975, Devo and filmmaker Chuck Statler made In the Beginning Was the End (The Truth About De-Evolution), a low-budget 16mm short film. One scene had Mothersbaugh delivering “Jocko Homo” as a lecture while human larvae writhed on a conference table. The film won the next year’s Ann Arbor Film Festival, and the film toured the country, which is how A&M Records man Kip Cohen first heard of Devo. Two months later the label gave Devo $2,000 to drive out to Los Angeles for a 45-minute showcase set at the Starwood nightclub. Cohen left early. But Devo decided to stay in L.A. People actually liked them out there, got the music and the message. Shows were sellouts.

Devo also made the trip to New York, played CBGB’s and found inspiration from the punk scene there, trimming the fat from their exotic dirty blues sound.

“We listened to the Ramones and Sex Pistols and other bands, and we’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is great.’ And when our songs are 50% faster, they sounded better,” Mothersbaugh says with a laugh.

At the legendary New York rock club Max’s Kansas City, Bob Mothersbaugh would unfurl his guitar solos while walking over the tables of the audience. Among them were some new fans. One night, John Lennon walked up to Devo’s frontman after their set and sang the opening line from “Uncontrollable Urge” right into his face: “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah!”

On another night, as seen in the documentary, Bowie introduced the band to a full house. They were embraced at that time and in the coming years by many artists they respected, from Iggy Pop to Neil Young.

“What they thought mattered. If David Bowie likes you, if Iggy Pop likes you, if Neil Young likes you, you feel vindicated,” says Casale. “There were plenty of people that hated Devo. We were very polarizing. They laughed at us. They hated us, but we felt that same emotion straight back at them and that only gave us more resolve.”

By now Devo had adopted a new look, appearing on stage in plastic yellow Hazmat suits, a belt cinched tight around the waist, the proper uniform for a devolving world. And a new sound emerged on the band’s first real single, released on Devo’s own Booji Boy label: “Jocko Homo.” Here was a new anthem for a new age, describing the cracked Devo philosophy (“We’re pinheads now / we are not whole”) against a quirky anti-rock throbbing. The B-side was the sneering “Mongoloid,” which described all humankind as deluded genetic deviants.

Bowie passed his copy of the Devo demo to sometime collaborator Brian Eno, and at the Max’s show Eno offered to produce Devo’s first album. He would even finance the recording himself, certain Devo’s inevitable signing to a major label would mean a quick return on his investment.

Eno brought Devo to West Germany, to Conny Plank’s studio in Forst, near Cologne. It was home to a certain brand of conceptual electronic music and to the German “head bands,” the likes of Guru Guru, Birth Control, and Mobius. Eno often worked there. It was cheap and isolated, a converted farmhouse and pigsty.

The producer had many ideas for the record, but Devo were extremely protective and controlling. And many of the bits and pieces Eno recorded on various tracks (some with Bowie) didn’t make the final mix of the album.

“We freaked him out and he freaked us out a little,” says Mothersbaugh of their Eno experience. The singer still has dreams of handing Eno back the old multitrack tapes for a new remix.

Regardless, when the sessions were over, Devo and Eno had created something crisp and frenzied, a seething, desperate rock and roll record, both a warning and a joke about the coming pop future.

The album began with strange echoes from the pop past, filtered through the Devo brainpan. “Uncontrollable Urge” lifts its first four bars directly from the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Then comes Devo’s frantic, and to many a deeply disturbing, reconstruction of the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” The Jagger/Richards tune was like a holy text then, a beloved Baby Boomer anthem of apocalyptic lust, transformed here into something spasmodic and weird, inspiring new waves of love and hate for Devo.

The documentary includes a clip from Devo’s intense performance of the Stones classic on Saturday Night Live, and the song is sped up even further. The five members face the TV cameras in their yellow Hazmat suits, and perform the song with twitchy, robotic movements, terrifying and thrilling a new generation of music listeners watching at home.

“It would not be an exaggeration to say at least a hundred people have come up to us through the years backstage and said, ‘The first time I ever heard you guys was on Saturday Night Live, and you scared the shit out of me,’” Mothersbaugh says with a laugh. “That’s a very typical response that we all get.”

After a second album, 1979’s Duty Now for the Future, with songs from the same body of work, Devo hit the mainstream in a big way with their third release. The robotic R&B-flavored Freedom of Choice, from 1980, included the unlikely pop hit “Whip It.” The song reached the Billboard Top 20 and had a provocative Western-themed music video that had Mothersbaugh with a bullwhip.

As a rare band with the foresight to create music videos since their earliest records, Devo were also in regular rotation on the still-young MTV network. Soon, the band was headlining major venues, from Budokan in Tokyo to The Forum in Los Angeles.

“We wanted commercial success, but for us, it was more important to be artistically true to ourselves,” says Mothersbaugh. “We wanted to figure out how to do that.”

The final third of the Devo documentary shows the triumph and disappointing aftermath of the band’s success. The record company wanted a series of hits like “Whip It,” but the band had already moved on. Their third album, 1981’s New Traditionalists, included several now-beloved Devo standards—“Beautiful World” and “Jerkin’ Back ’N’ Forth” among them—but no hit singles.

By the time of Devo’s final album with Warner Bros., 1984’s Shout, band members were experiencing creative differences for the first time. Things began to fray.

“I don’t think any of us feel like we love it,” Mothersbaugh says now of that record. “By the time we got to Shout, me and Bob Casale were the only ones that were showing up for rehearsal and writing.”

Devo were bought out of their deal with Warner and moved to indie Enigma, which soon went under. Devo likely could have found a new label, but chose to go on hiatus.

“I think bands are like bacterium in a Petri dish and you watch it grow, grow, grow, and then it starts to go away,” Mothersbaugh suggests. “Some of them are a really strong bacteria, like the Rolling Stones. They had a bunch of great stuff for a long time. I think it’s part of the cycle, and you’re lucky if you have four or five albums that you like before you fall apart. When you’re unlucky, you only have one album.”

As the documentary ends, the Devo story comes to a semi-happy conclusion, with the band seemingly over, but Mothersbaugh finding a new outlet as an in-demand composer for film and television under his Mutato Muzika banner, bringing along the two Bobs. And Casale began a busy career directing music videos and TV commercials, often showing some of the classic Devo visual flair.

They returned to Warner Bros. for the 2010 comeback Something for Everybody, which reached the Top Ten of Billboard’s rock and alternative album charts. Bob Casale died in 2014 at age 61. (Drummer Alan Myers, who left Devo after Shout, died in 2013.)

In 2025, the band is active, but have no immediate plans for another studio album. Devo exist mainly onstage, often facing audiences filled with new fans born decades after Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!

Meanwhile, a lot of the hitmakers that filled the charts back in the ‘80s are long forgotten, and Netflix isn’t commissioning documentaries on them. Five decades later, Devo are somehow still relevant, as society continues its de-evolutionary decline.

“Why are people interested in Devo?” asks Casale. “We didn’t have a dozen No. 1 hits. We didn’t sell a hundred million records. We weren’t Elton John. It’s because of the thing that we did do, which is a cohesive body of work driven by a few big ideas.

“There’s still vital energy there, there’s still meaning there,” he adds. “And there’s now three generations watching us because they discovered it through the internet. And it’s kind of cool.”

Leave a comment