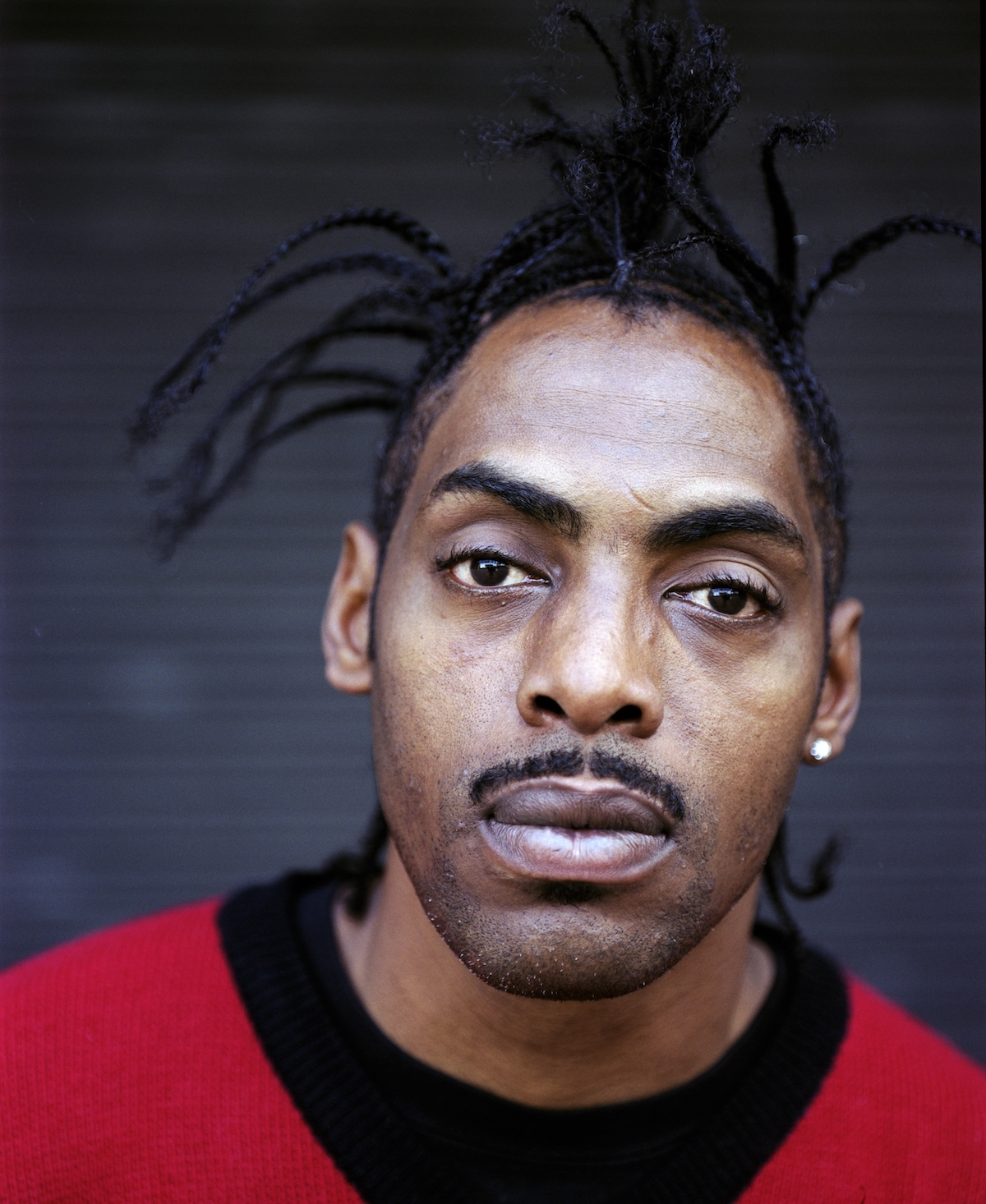

Before he was Coolio, Artis Leon Ivey Jr. was just a kid growing up in Compton and South Central Los Angeles, at a time when middle class hope gave way to something very different. “Compton was actually a well-to-do area until the 1980s when Ronald Reagan ushered in the crack era,” said Coolio’s longtime personal manager, Jarel “Jarez” Posey, who lived with the rapper for 10 years. “Even though he battled with that, he found a way through music to fight.”

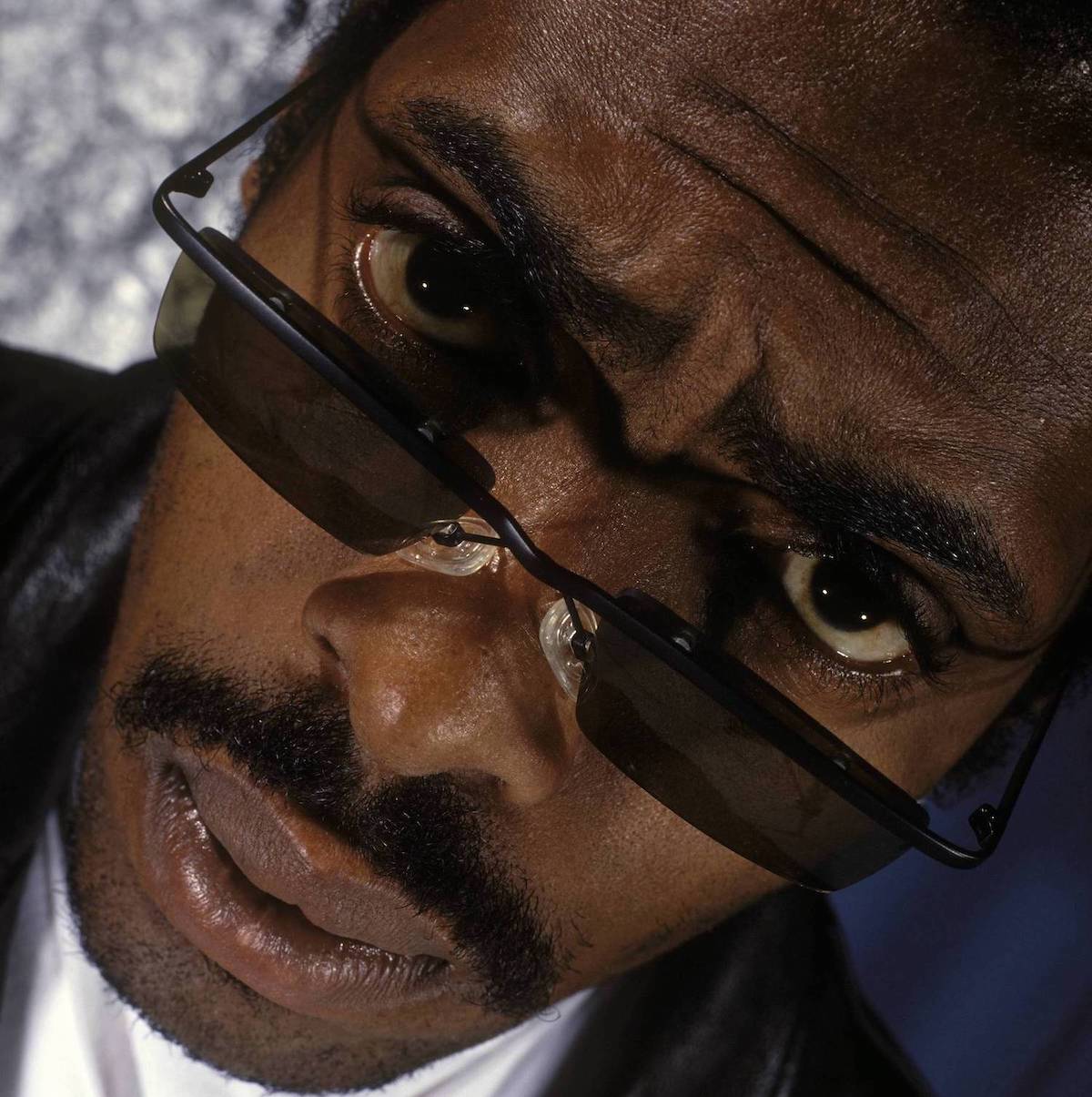

Coolio died on September 28, 2022 of an accidental overdose, still touring and performing until the very end. His breakout 1995 single, “Gangsta’s Paradise (featuring L.V.),” became a global phenomenon. The track dominated the 1996 Grammys, was parodied by Weird Al, and earned a legacy few rap songs have matched. In his final years, Coolio moved with that same blend of charisma and unpredictability, once even spending time abroad with heirs to the Prada fortune, according to Posey. “Gangsta’s Paradise” had taken him places he never could’ve imagined, but it was always rooted in where he got his start.

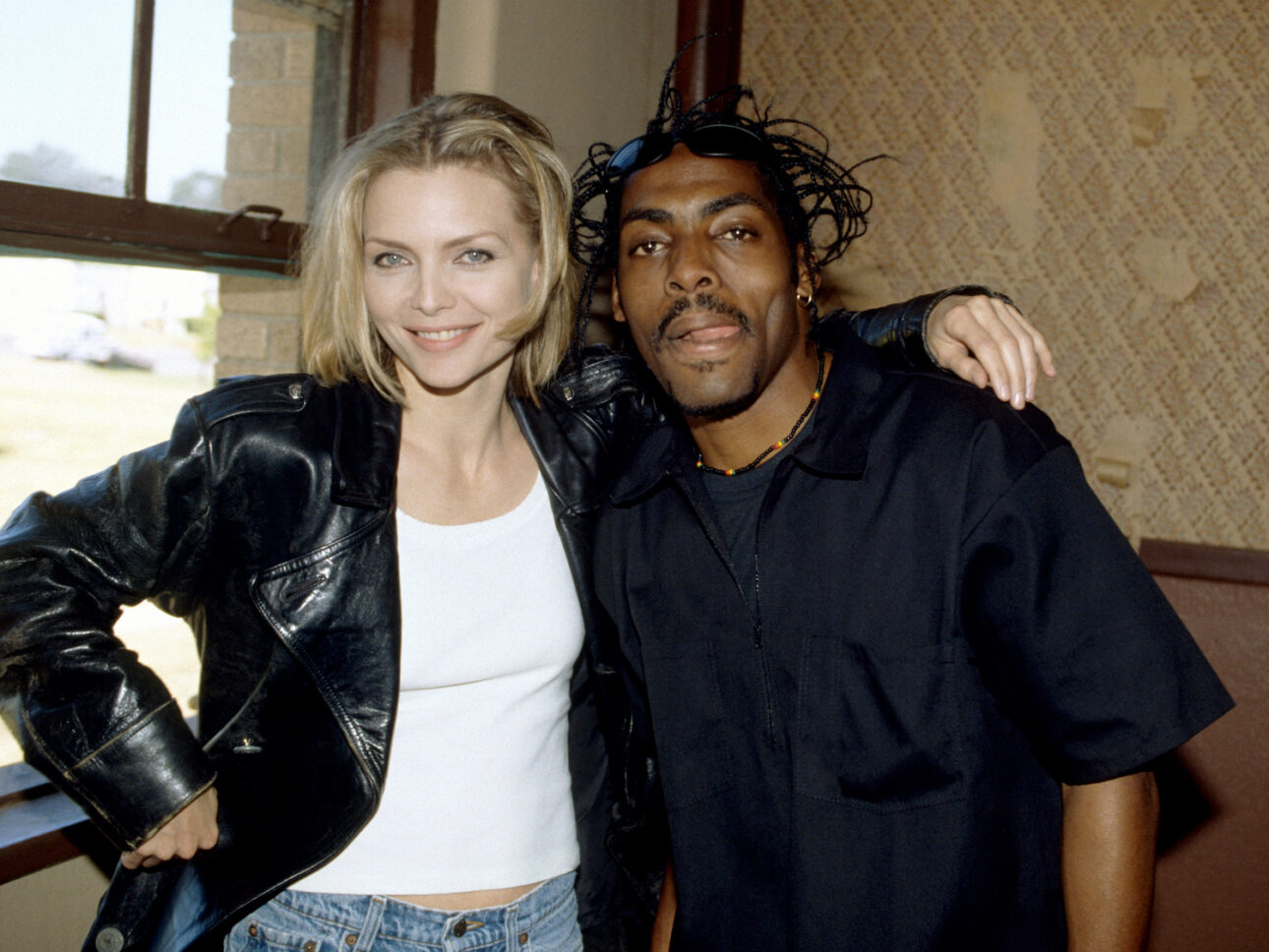

“Gangsta’s Paradise” dropped August 1, 1995, on Coolio’s sophomore album by the same name, just a year after his hit “Fantastic Voyage.” But this was a different kind of ride. Propelled by the Michelle Pfeiffer film Dangerous Minds, a moody music video from young director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day), and a haunting sample of Stevie Wonder’s 1976 track “Pastime Paradise,” the song transcended rap culture. And as those involved with the track recall 30 years later, Wonder wasn’t even keen on a collision with rap initially.

“Gangsta’s Paradise (ft. L.V.)” producer Doug Rasheed went on to produce for the likes of 2Pac (“Only God Can Judge Me”), Whitney Houston, and Barry White.

Then there’s vocalist L.V. (born Larry J. Sanders) whose chilling cry, “Why are we so blind to see that the ones we hurt are you and me,” helped turn “Gangsta’s Paradise” into something spiritual. Though his name may not ring out like Nate Dogg’s or Jewell’s, L.V. was a fixture of ’90s West Coast gangsta rap, lending his soulful voice to countless tracks with L.A. collective South Central Cartel. He later released his own solo version of the track on his 1996 album, I Am L.V. And he’s quick to point out that the choir you hear in the background isn’t actually a group, but all him—layered and harmonized into a one-man gospel.

To mark 30 years of “Gangsta’s Paradise,” we spoke with some of the key figures behind the song and those who witnessed firsthand how it transformed Coolio’s life and legacy, including producer Doug Rasheed, vocalist L.V., manager Jarez Posey, and talent representative Sheila Finegan—each offering a piece of the puzzle behind one of hip-hop’s most enduring anthems.

Before paradise

Doug Rasheed (producer): I grew up in San Diego. My dad is a musician, so I grew up in a house with music. Ended up playing bass guitar, which I did from around 15 years old. I was a bad kid in the streets. A lot of people don’t realize this because San Diego is known for beauty and all of that. But, you know, in the hood, it’s extremely gang related. So I ended up going to Japan to play in a band, to get away from some potential trouble. And it changed my life. I was there from 1988 to 1989 and came back in ’90.

I started getting into making beats and stuff, because I had just bought this little keyboard to kind of make music while I was over there to kill the time. But I fell in love with it, and I realized I was pretty decent at it. By the time I got back, I was determined to build a little studio and start learning how to produce. Back in San Diego, I made a lot of beats for local rappers—$100 a beat.

So I eventually went up to L.A. in 1993 to try to meet people and got a job as a security guard at Sony Pictures Studio and ran into Paul Stewart. He was managing Coolio, Montell Jordan, and this female R&B group called Y?N-Vee. So Paul was working and wanted to park in my lot. I kinda traded him: Listen to my tape and I’ll give you some spots and you can park here every day. I played him one beat and he was like “Oh, I like this.” So I did a song on Coolio’s first album. That’s how we parlayed it, that hustle game.

L.V. (singer): I was born in South Central, Los Angeles. I came up doing music with South Central Cartel. I’ve been singing from the sixth grade all the way up. One of the members, I went to high school with. He goes by DJ Kaos and his real name is Gregory Scott. They was pop lockin’, robot dancing, and I was singing. So I went from singing in talent shows at Fremont High to Los Angeles Trade Tech. From Trade Tech, I used to sing in the choir with my music director and from there I went to Los Angeles Southwest College.

I got with South Central Cartel in 1991. Gregory turned me on to Prodeje, my homeboy, a big rapper from SCC. A lot of people don’t know this but Havoc & Prodeje from South Central Cartel came before Mobb Deep. Sure did. They had a little problem about that but then that was resolved. I was singing one day on the corner. Gregory and Prodeje asked me if I would like to sing in their rap group and I’m like, “Yeah, that’s no problem.” So I did my singing thing with them. The first song I did with them was “Ya Getz Clowned” (1992).

Risking it all

DR: The way that “Gangsta’s Paradise” came about was that me and Paul Stewart risked it all by leasing this mini mansion from jazz legend George Duke in the Hollywood Hills. We was just in the house throwing parties and doing whatever trying to brand ourselves as successful in the game. My studio was right there in the house.

Paul, he’s a DJ. So he had a record collection, I got a record collection. I got about 3,000 wax albums—my mom’s collection growing up, everything. So we would get into these contests when we would try to see who could pull out the dopest sample, and whoever won, I would flip it and make a beat out of it. So that day, I pulled out that Stevie Wonder “Pastime Paradise” sample. This was in mid-1994.

Stevie’s Songs in the Key of Life is one of my favorite albums. I grew up on that music. I knew that if I pulled that album out for that contest that day, that I was going to be able to find something. When I listened to it, I said, “Oh, man, this will be tight. Man, I can flip this,” because it got the little intro with the strings. So I took that sample, and I kept working with it, and then I started working with L.V. who was also under Paul’s management.

L.V.: I walked into the studio one day while Doug was producing and asked, “Whose track is that?” I asked if I could have it and he said, “Yeah, no problem you can have it.” So I got the track and went to my lead rapper, Prodeje. He’s like, “Nah, man. What you were singing was tight, you just need to sing the whole song.” I had already done the hook. Like everyone knows, that hook is from Stevie Wonder but I did it my own way and wrote my own lyrics. The choir that you hear is no choir. It’s all me. Doug had already mixed me.

I was basically telling the story about how things go on in South Central, man. Most of the people who live in the community as far as ghettos are concerned out here, everybody was living in a gangsta’s paradise. I sung the hook, then I sung the other part, “Tell me why are we so blind to see that the ones we hurt, are you and me?” I’m talking about Black people hurting Black people, period. Everybody gets hurt around the world. But it was more serious in the ghettos out here. This was the message I was sending and God sent those lyrics to me. Man, they just came. As you know, the song did what it did, and man, God took over.

DR: It’s L.V. singing a three-part harmony. Then we recorded it in the studio and then I had the demo vocals that we did. I blended them together and it just came to life. It actually created an overtone, a note that’s not there. You hear it, but nobody sings it. So it just had magic all through the track and I think that magic is still there today.

We were going to do it on L.V. with just him singing. But Coolio was the only one who had a record deal, to be honest with you. Montell Jordan didn’t have a record deal at the time. Y?N-Vee didn’t have a deal. L.V. didn’t have a deal. Nobody did, only Coolio. So he comes in and hears the beat and is like, “Hey, wait a minute, Doug you did that?!”

The pen took over

Jarel “Jarez” Posey (Coolio’s longtime manager): I know Coolio’s version verbatim because he was a storyteller and he was very animated about how he told stories. The way he tells it, when he went to pick up a residual check for “Fantastic Voyage,” from Paul Stewart’s house, Doug and L.V. were in there, messing around in Paul’s studio. When Coolio heard what was going on, he turned to Doug and was like, “What you got going on there? Whose is this?” So Coolio was like, “Let me sit down because this is mine.”

So he started writing and not one time did the pen ever come up. He said he wrote the song like he already knew the song. He said that when he heard the music, something did take over him. I believe he only took out one thing and that was a cuss word because of Stevie. He was vibing so hard off the music that he was just in it.

So he left there with the cassette tape, played it in his car, and went to his old neighborhood to go play it for some of his old neighborhood friends. They were like, “It’s alright.” They didn’t give him the feeling that he really wanted, and he didn’t understand that. He overnighted it to Tommy Boy [Records], and there was a similar reaction. But they thought that maybe it would be an album cut.

Over time, a change of hands was made between Paul Stewart and Josefa Salinas, who was Coolio’s wife from 1996 to 2000 and also his manager before I was.Josefa had a friend that did acquisition for Disney. Josefa came from Power 106 so she was very versed in radio. She heard the song and maybe a day later said she knew about this movie that wasn’t doing too well behind the scenes because something was missing. That movie was Dangerous Minds. They paired “Gangsta’s Paradise” with the movie, had another testing, and the ratings jumped out of the roof.

Flying high at the Grammys and AMAs, splitting apart

L.V.: The Grammys was crazy, man. They called us to rehearse. We doing our thing. I met Kenny G and Luther Vandross. Then there was the American Music Awards. As I’m singing my part on stage, Stevie Wonder comes out of the back and started singing, too. I was more surprised than anything. I almost got choked up, but I knew I had to keep singing because I’m in front of thousands of people. So I couldn’t just stop. All my life, I wished that I would sing with Stevie Wonder. My next dream was to meet Luther Vandross. So everything was lining up for me. Even now I get excited when I see the video.

DR: I really, really blossomed after that record. That’s when I really started to work with 2Pac, Whitney Houston, Brandy, LL Cool J, and Barry White. Even though “Gangsta’s Paradise” is my biggest record, I think some of the people I worked with after that were much larger with respect to the caliber.

I never met Fuqua or Pfeiffer. By the time they did the video, the crew kind of broke apart, let’s just put it like that. I don’t want to throw nobody under the bus. But let’s just say it got real funny when the money was about to happen. We never really had a falling out so to speak. But just in the process of trying to negotiate, get the contract done, I didn’t like what was being proposed.

Stevie Wonder took about 75% of the publishing and me, Coolio, and L.V. split the remaining 25%. But even with all of that, it’s a lot of money that we all made.

JP: Once the song blew up, Tommy Boy changed their whole profile. Tommy Boy wasn’t no joke. They had Queen Latifiah. But “Gangsta’s Paradise” kinda usurped all of that and Tommy Boy became synonymous with “Gangsta’s Paradise.”

There was some animosity and resentment at the time. I understand L.V.’s point of view, too. But Cool’s point of view was this: The powers that be ultimately chose him. But L.V., he wanted that same sort of recognition, but it wasn’t Cool’s to give. It’s like Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5. Cool didn’t choose that.

Paradise lives on

L.V.: We never knew the song was going to be as large as it was. That song hit nice, big, and it’s still hitting. I’m still thanking God for the blessing that he gave me. I’ve done some hooks for different people but I didn’t just want to continue doing hooks. I have Large Variety now, that’s my independent label, with songs like “Party With Me.” I just went to New York to be on Last Week Tonight With John Oliver. I’m still doing my thing bro, 64 years old but I ain’t missed a step.

DR: Me and Coolio actually kinda came back together after time went by. Ran into him at a club. We get to talking and we’re like, “What happened? Why did everyone fall apart like that?” And no one could really come up with a reason. He said, “I was just mad at you.” I’m like, “About what?” And he’s like, “I don’t even know.” So we made good. I was really glad we did that before he passed away..

What Coolio wrote on that track, the way he delivered those vocals and wrote those lyrics, it brought everything full circle. One of the things I noticed, today and even back then, everyone from older people to kids—everybody knows that song.

All of my memories of Coolio are pleasant, positive memories. He was a funny dude. Full of good, positive energy. A real hustler. I learned a lot from him about diversifying my talent which is what I do now. I write screenplays and I got my book coming out, From Rags to Gangsta’s Paradise. It talks about changing my life, chasing my dreams, and then finding them.

Sheila Finegan (Coolio’s talent representative): I’m originally from Nebraska, headed out west in 2009 with my family just like the Beverly Hillbillies. How I actually met Coolio was at the airport in Dublin, Ireland. I went up and asked him to do a video and say happy birthday to my friend. So we started a beautiful friendship that day and I was with him until the end of his life.

’90s rap was a big part of my growing up. The last time I saw him, we were at Jimmy Kimmel, just a couple of weeks before he passed away. It was such a Coolio day. He always gave me gray hair. Somehow he lost his Gucci fanny pack. So he was late on his plane but I had gotten to Jimmy Kimmel early.

He would match his clothes from head to toe, and he had the wrong colored shoelaces that day. So I had to go run up and down Hollywood Boulevard looking for brown shoelaces. One of the things that makes me sad is that they did the Mean Tweets with him. It never aired because he passed away a couple of weeks later, but it was so funny. That is the last time I saw him. I was excited to take him back to Nebraska, but unfortunately he passed away.

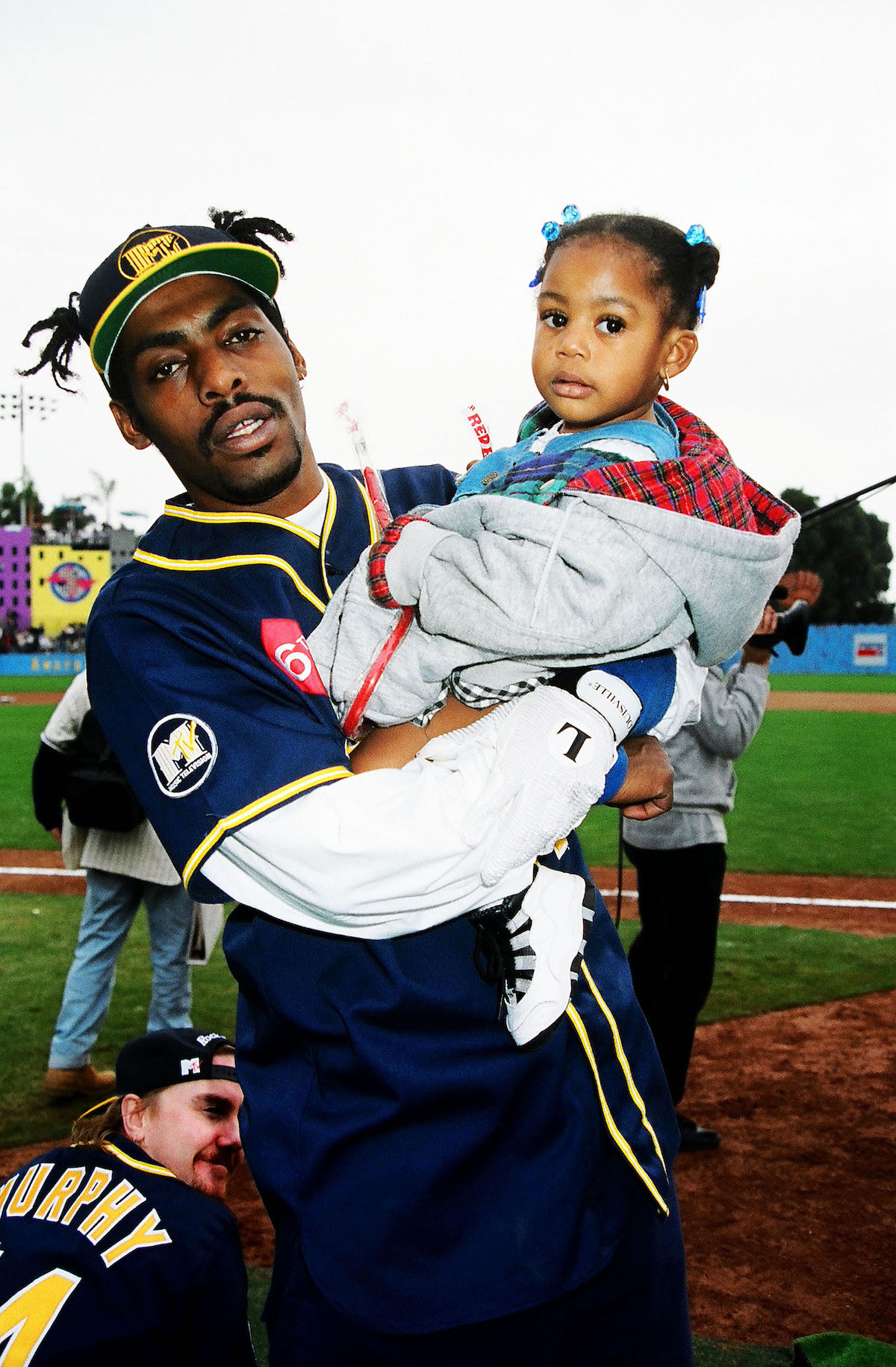

JP: I’m a smooth jazz artist, got a couple of Billboard No. 1s. Me and Coolio met when I was 18 years old, in maybe 1997. I’m 46 now. I ran into him in the city of Carson and he saw me playing saxophone. He said that he had a studio session in Hollywood. So I left my car there and we just went up to Hollywood.

I basically started hanging out with him. He had a 20-car garage with a weight room and game room. He loved to play video games. We would play Madden til 4 o’clock in the morning. One day he asked me, “Where you be sleeping when you leave here?” I told him that sometimes I slept in my car. So they gave me a room. This was around 1998 or 1999.

Eventually everything was put on the table for me to be his manager. I had to figure it out fast: the dynamic of touring, television, movies, and music.

He was such a charismatic entertainer. Well-read and spoken. He grew up a book nerd, pretty much. He always had to read every night. He loved fantasy books, reading about dragons. Game of Thrones was his stuff but even before that.

We moved to Vegas to get out of the everyday bustle of L.A. and slow it down. But it didn’t really slow. It kind of affected him a little bit. I could see that traveling was wearing and tearing on him.

Not only was I his manager, I was there to protect him. I felt very, very responsible for him. To the point where I was actually getting ready to go on a plane to go to where he was the night before he passed away, but the flight got canceled. I talked to him every hour on the hour, til two hours before he passed. I think he would say that the song is still alive and thriving and we would still be doing major shows. We never stopped. The week that he passed, we were on a two-week major tour. It just meant a lot to everybody.

Leave a comment