In 1993, when Darryl Jones heard Bill Wyman was leaving The Rolling Stones, he called Mick Jagger’s team and asked to audition. Jones, who had already played with Miles Davis, Sting, Madonna, and Peter Gabriel, joined the band after two rounds of auditions.

Since 1994’s Voodoo Lounge, Jones has played on every Stones album. In the new documentary Darryl Jones: In the Blood, premiering October 7, the band all express their admiration for his extraordinary gift.

In the documentary, Mick Jagger says he respects him highly “as a player, as a musician.” So does Keith Richards. “Darryl is the most solid cat. My solid left arm, one of the best bass players in the world.” He thinks of Jones as an older brother, even though Richards is older.

“It’s funny because I feel the same way about Keith. I feel like he’s my older brother. He’s a lovely guy. And it’s not just in the way that he plays guitar. It’s in the way he writes music. He has an artful way of doing everything,” says Jones, via Zoom from his home in Los Angeles.

After Charlie Watts died, Jones wrote a beautiful tribute for Jazz Times and hosted a concert in his honor at the Blue Note in New York City. “Jazz is what we shared. And we loved shoes,” he says.

The stylish Watts would take him on shopping trips in London and Tokyo, to visit his impeccable tailors and shoemakers. With his trademark dreadlocks, scarves, and fedora, Jones has a distinct style of his own.

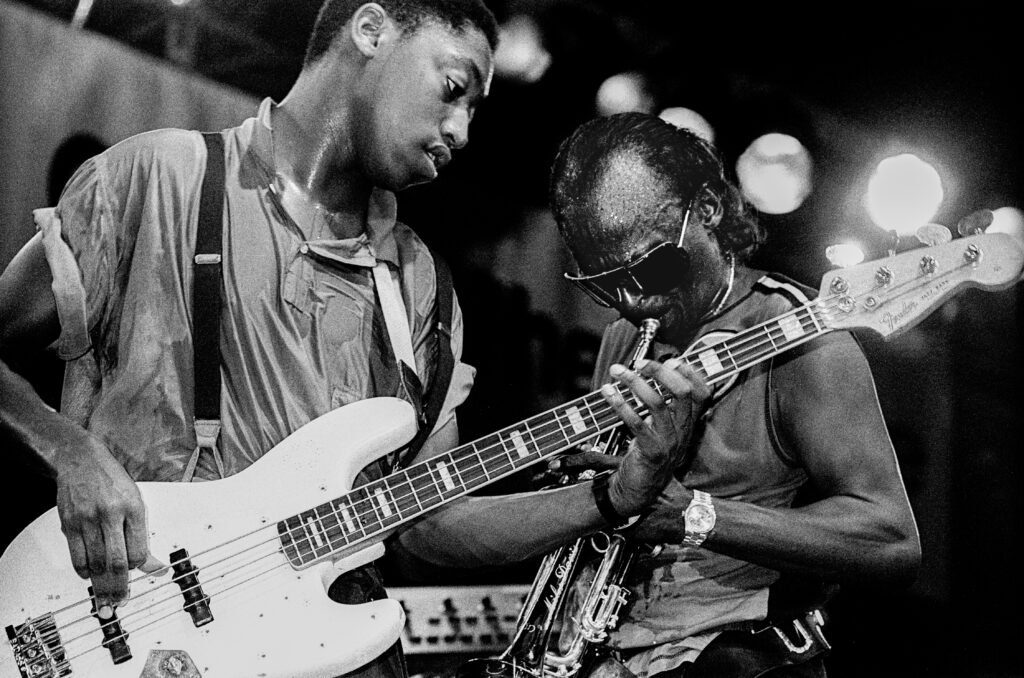

When only 21, Jones joined Miles Davis’ band. His first recording with Davis was the jazz fusion album Decoy, in 1984. Working with Miles transformed him as a musician.

“What I learned from Miles is a kind of active listening, where you are listening to the musicians around you instead of playing what you practiced. You are allowing what you play to be informed by what you are hearing. If you think about listening to a friend and being there for them, really listening, that’s an act of love,” Jones tells me..

“I think it’s one of the reasons why I’ve been able to move into these different circles and do different things. I’m in love with listening.”

Jones’s father played drums and turned him onto music as a child. His mother loved James Brown and started taking him to his concerts when he was seven years old. She volunteered at Jesse Jackson’s Operation Breadbasket and a health clinic founded by the Black Panther Party.

His parents taught him to take pride in being a young, black man, and showed him what he needed to change to be treated equally.

These early influences shaped how he thinks about the role of artists in society. He admires songwriters who address issues like racial justice, citing Curtis Mayfield, Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Jimi Hendrix, and Nina Simone.

“I think it’s important artists comment on the world. It’s us doing our part to move the conversation further about things that need to change.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

On a break from touring with the Rolling Stones, Jones is recording tracks for his first solo album in Los Angeles.

When I ask about his creative process, he says, “Miles encouraged me to draw, to paint, to cook, and take photographs. He said one art helps the others. That’s the space I’m trying to move into, where my creative urges are.”

In the documentary, Jones sings one of his original yet-to-be-released songs with the chorus: We’re heading for a revolution, a conscious revolution. The song is called “Conscious Revolution.”

“The revolution,” he says, “in many ways is how we’re able to develop our consciousness. That is what changes things. The truth is that the world is both wonderful and terrible. There needs to be a revolution of consciousness.”

I tell him this reminds me of Bob Marley’s famous words: Emancipate yourself from mental slavery.

“I think of artists being ahead of change and revolution. Look at Bob Marley. One of the reasons why maybe he was taken off the playing field, if you believe that to be the case, was because he had so much power to change people’s minds,” he says.

With the Darryl Jones Project, Jones sings his own songs with a backing ensemble, a fusion of jazz, soul, and blues. He is currently working on his debut album for the project in Los Angeles. In addition, he’s played on a new album for Beach Boys and Rolling Stones collaborator Blondie Chaplin. Drummer Charley Drayton, who plays with Bob Dylan, joined him. “It’s a labor of love. Charley is one of my dearest friends and such an amazing musician. And Blondie is an incredibly gifted songwriter, singer, and performer. It’s not just about the music. The brotherhood and sisterhood of music have made my life so much more rich,” he says.

Lately, he has been reading Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of Music. “Some of the stuff in this is heartbreaking. Some of these guys are being subjected to the most racist treatment, not only by law enforcement but by managers and club owners. At the same time they are dealing with that, they’re creating Bebop, an American art form, birthed in this country.”

Jones sees songwriting as a catalyst for social change and personal healing. He says his song “Games of Chance” is about resilience and going through difficult times. When he listened to it, he felt relief. “It healed me. When you have all of your thoughts and feelings in this song, I feel like if it can be healing for me, then probably it can be a source of healing for other people.”

He encourages those who want to have a career in music to have an open mind and avoid what he calls musical snobbery.

“You weaken yourself when you decide that this music is the music. There’s so much to learn if you are willing to delve deep. If you’re open to different kinds of music, the soul of those different kinds will find you.”

Leave a comment