Freddie Gibbs realized his artistic appeal years ago. See the haunted closing lines from “BFK,” the title track of his 2012 mixtape Baby Face Killa: “Got a slug for the judge, bringin’ heat for police / And a book full of sins that I reap when I sleep / Then I wake up, and I put ’em on a beat; how you love that?”

It’s a three-line summary of a catalog that now spans three decades: Gibbs menaces authorities while revealing past felonious trespasses have turned his dreams into nightmares. Ever self-aware, he breaks the fourth wall and arches an eyebrow at his audience. He knows that shuttling between conviction and contrition makes him the perfect gangster antihero, a Tony Soprano-like figure whose sins are as captivating as him grappling with them and grasping at redemption.

In hindsight, though, Gibbs was also rapping quite literally.

“I’ve never quite seen anybody record like Freddie records,” Norva Denton, SVP of A&R at Warner Records, explains over Zoom. “He’s going to smoke, drink, and eat, and at some point, he’s going to fall asleep.”

Denton has followed Gibbs’ career from “BFK” onward, trying to sign him twice (once to Motown and once to Warner) before Gibbs agreed to partner with Warner for his major label debut, $oul $old $eparately ($$$). Credited as A&R, executive producer, and composer, Denton worked closely with Gibbs and his longtime manager, Ben “Lambo” Lambert, for three years on $$$. During recording sessions in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Miami, and Chicago, he witnessed Gibbs’ countless studio naps and every subsequent lyrical feat.

“It’s the weirdest thing in the world because [Freddie’s] never really asleep. His head is nodding the whole time … It sounds unrealistic, but he’s literally rapping while he sleeps. By the time he wakes up, maybe two or three hours later, he needs maybe another 30 or 40 minutes, and he’s going to get up, go into the booth, and recite the whole fucking verse. To this moment, I still don’t quite understand how he does it, to have a stream of consciousness where his brain can go on autopilot,” Denton says. “Imagine somebody rapping the hook, the bridge, and the verse in one take without a pen and paper. That shit is uncanny.”

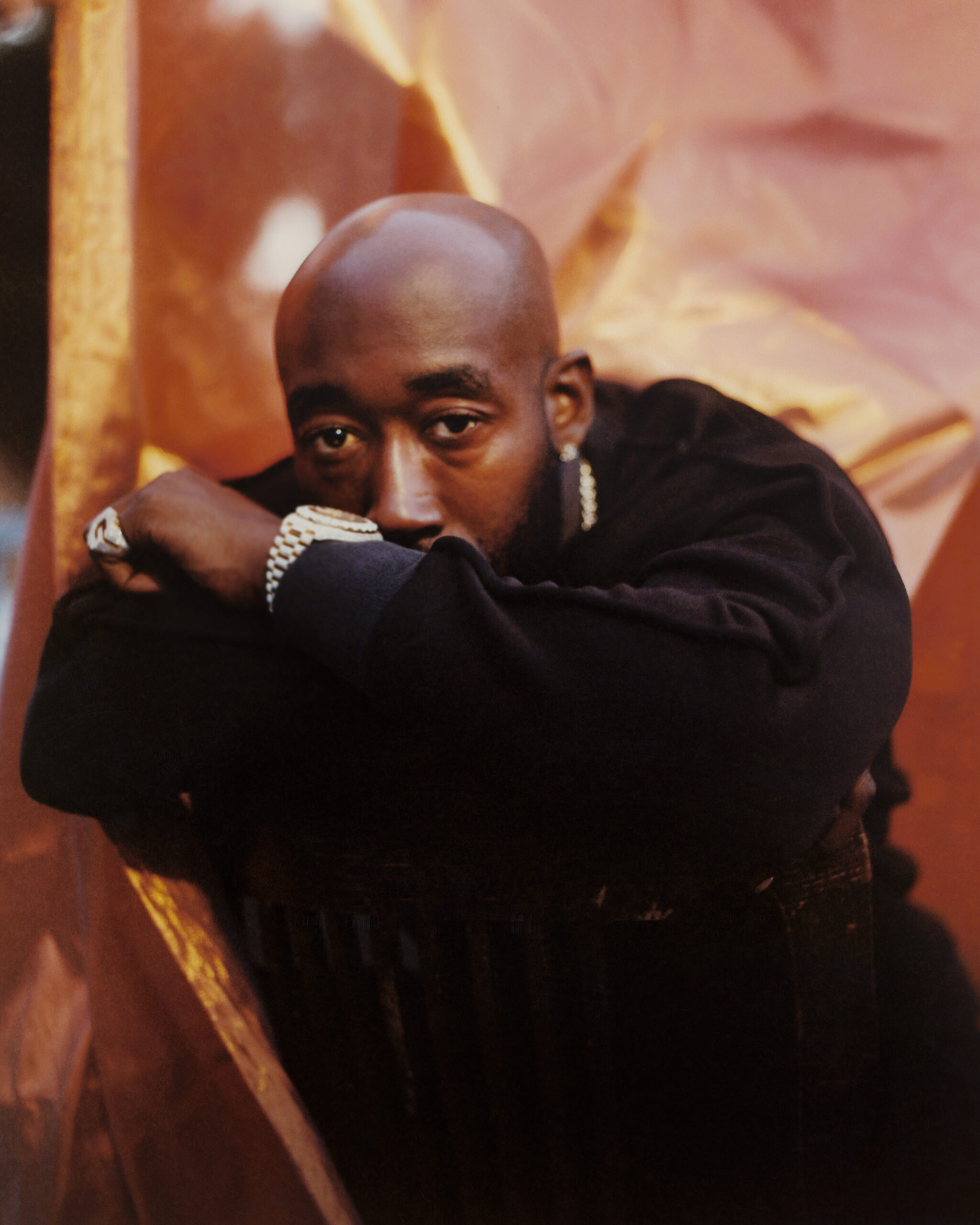

The day before our Zoom conversation, Denton joins Gibbs at the Sheraton Universal Hotel in Los Angeles, where Gibbs has lived since leaving his native Indiana, in the late 2000s. Despite the maddening traffic clogging the 101 freeway on this late Tuesday afternoon, Gibbs strolls through the automatic lobby doors of the four-star hotel 10 minutes early. He’s either unfazed by late September’s humid heat wave or accustomed to moving between air-conditioned spaces, wearing a thick, light gray Palace hoodie, black shorts with a floral print, and pink and powder blue New Balances. It’s a comfortable yet sporty look that, with his lanky yet athletic physique, makes him seem like a tennis player trying to keep his limbs warm before a match.

More than warmth, the 40-year-old father of three and Grammy-nominee (for 2020’s Alchemist-produced Alfredo) needs fuel for his final interview of the day, the one standing between him and the latest in a series of celebratory evenings preceding the release of $$$. “Can we do the interview in the restaurant?” Gibbs asks when we shake hands underneath one of the lobby’s gold and glass chandeliers. “I’m starving.”

Perched on a stool at a high-top table adjacent to the hotel bar, Gibbs eats and drinks most of the conversation. He chases tortilla soup with a Sprite and a Hennessy sidecar, ordering a second round before his prime rib arrives. An incorrigible joker on Twitter and Instagram, which has deleted his account numerous times, Gibbs often begins answering questions only to pivot to discursive comedic riffs. Maybe he’s entertaining himself after weeks of interviews and post-album listening party Q&As; maybe it’s the alcohol; or maybe he’s spent too much time hanging with Jeff Ross, Joe Rogan, and Slink Johnson, the comedians who provide voicemail interludes on $$$. Many of these hilarious tangents only work in context and with Gibbs’ delivery, but here’s one that doesn’t require much explanation.

“Rick James is one of my favorite artists and wrote one of my favorite autobiographies. When I read his book, I was really hooked on him. If you do music, you should read Glow. That documentary compared to the book was trash, but n—– can’t read. Half the population is illiterate, so I get it,” Gibbs says when asked why he recreated a photo of the late funk and R&B icon for $$$. Then comes the pivot and the punchline: “You want to diss a rapper? Make them read out loud. That’s why n—- is like, ‘I’m going in the booth and don’t need no paper.’ You can’t write it! You can’t. I don’t need paper, either. But you know what? If I had to write it down, I could. Let’s have a ‘Rappers Read Out Out Loud’ contest.”

Jokes aside, Gibbs is thoughtful and attentive, leaning in to hear questions over the rising din of happy hour at the bar, and always speaking in the direction of the recorders sitting on the table. This combination of focus, conscientiousness, and conviviality partly accounts for his staying power and continued rise in rap. Of course, there’s also his seeming agelessness. Gibbs has matured as an artist, but his music never feels old.

“I get better every album. I get younger every time,” Gibbs says. “I’m like Benjamin Button or some shit. I feel like a new artist every time I make an album.”

To comprehend the improbability of Gibbs’ gradual yet indefatigable ascent from major label casualty to a critically-acclaimed independent icon to Grammy-nominee and major label priority, you have to go back in time and remember a younger rap industry. Gibbs released his first mixtapes, which caught Lambo’s ears as an Interscope intern, in 2004 and 2005 while selling crack and robbing trains in Gary, Indiana. Drake was still Wheelchair Jimmy. Tyler, the Creator wasn’t even yet beefing with blogs. Kendrick Lamar was probably recording at a home studio in Compton, a decade and change away from rap king coronation and a Pulitzer. Future hadn’t yet changed his name from Meathead, and Young Thug was still Jeffrey Williams, a quarterback at Washington High. In other words, when Gibbs signed with Interscope in 2006, he preceded the most notable commercial rappers of the last two decades.

Kanye West dominated the commercial rap landscape in the latter part of the 2000s, as did pop and R&B crossovers. (The fewer T.I. songs you remember, the better.) Mixtape-era Lil Wayne thrived and drove promethazine prices through the roof, but gangster rap, trap rap, and anything remotely “lyrical” was quickly phased out of commercial rotation. After an internal label shakeup, nobody left at Interscope knew how to market Gibbs. A gravel-voiced, unprecedented hybrid capable of 2Pac’s thug intensity, Scarface’s grim diaristic writing, and Bone Thugs melodies, he made singular and sinister gangster rap for getaway car stereos. How were A&R’s going to convince DJs to slot his songs next to “Whatever You Like”?

There is an alternate timeline where Gibbs moves back to Indiana for good (and undoubtedly much ill) after Interscope dropped him in the late aughts. He’s reflected on those years a great deal in the weeks preceding $$$. Gibbs mentions that “Too Much,” the lead single from $$$, has become his first song to chart on commercial radio. It’s a major career milestone, but Gibbs breezes past it. Perhaps the reality hasn’t sunken in yet, or maybe the past is still too close in the rearview.

“I think about [getting dropped] a lot of times, and I cry. I was counted out 14 or 15 years ago. I’m not even supposed to be here right now, statistically, from a street standpoint and a music industry standpoint. The shelf life of an artist these days is fucking short. I was on the [XXL] Freshman cover in 2010.”

$$$ is equally reflective. Perhaps because Gibbs recorded many verses upon waking, the memories he relays are as fragmented and nonlinear as anyone’s dreams. Grim memoirs of starvation-motivated homicides and drug hustles in Gary bleed into post-Grammy-nomination celebrations; past heartaches give way to new trysts with IG models and baby mama drama. Gibbs is counting up with Pirus one moment, sitting in a jail cell for an unspecified crime the next. Like he has his entire career, Gibbs tempers ice-hearted malice and comically rendered disgust with bleary-eyed vulnerability and remorse, weed and liquor the only analgesics that afford him some semblance of peace.

While the timeline is slippery, Gibbs’ technical abilities are sharper than ever. He moves in and out of varied cadences with unmatched intricacy, finesse, and ease, a rap Steph Curry knifing through multiple defenders to penetrate the paint only to circle back and sink a three. As he has on past projects (e.g., 2015’s underrated Shadow of a Doubt), Gibbs reminds you of his Midwest lineage, delivering rhythmic speed raps and melodic, half-sung hooks like a lost member of Do or Die or Bone Thugs-N-Harmony.

[embedded content][embedded content]

If the above sounds characteristic of every Freddie Gibbs album you’ve heard, that was intentional. He hasn’t changed the product so much as he’s refined the recipe, wrapped everything in more regal packaging, and brought in more high-profile collaborators to endorse his wares. Only Gibbs, a perennial nonconformist who never aligned himself with a regional sound, could work with mainstream playlist mainstays like Moneybagg Yo (“Too Much”) and Offset (“Pain & Strife”), coke rap paragons in Pusha T (“Gold Rings”) and Rick Ross (“Lobster Omlette”), and revered icons from New York (Raekwon), Memphis (DJ Paul), and Houston (Scarface), without any of it feeling forced.

The album’s loose casino theme — conceived after wild, half-remembered casino nights and strung together with pre-recorded phone menus for “$$$ Resort & Casino” and those comedian voicemails — enhances its grand, idiosyncratic production. There are buoyant beats that could score sunset yacht cruises (e.g., “Lobster Omelette” and “Rabbit Vision”), while others should soundtrack the heart-sinking moment the dice come up snake eyes on an all-in bet (“Dark Hearted”). Madlib, Alchemist, Boi-1da, Kaytranada, DJ Dahi, Justice League—this truncated list of $$$ producers sounds conceived in a fever dream or pulled from a Reddit rap thread, but Gibbs has worked each of them in varying capacities before.

It’s an implicit testament to a back catalog that warrants regular revisitation, one that can stand next to the oeuvre of any working rapper you choose. Still, he branches out with assistance from Sevn Thomas, DJ Paul, and James Blake. Somehow, an architect of gothic Memphian trap and the U.K.’s post-dubstep poster boy produced back-to-back tracks for the first and probably final time in the history of recorded music. With assistance from Denton and Lambo, $$$’s flawless sequencing makes all of these otherwise disparate sounds and all of Gibbs’ verses feel part of a cohesive whole. After nine months of 2022 releases, $$$ is unequivocally one of the best rap albums of the year, a summation of the formal talents and musical fearlessness that have brought Gibbs to the precipice of mainstream stardom once again.

“It’s one thing to still be here, but it’s another thing to still be here and be fresh,” Gibbs says with a third Hennessy sidecar in his hand. “There’s a lot of motherfuckers here. There’s a lot of motherfuckers that, if this was a club, you’d have to let them in because of their past accomplishments. If we were basing it on relevance, there would be a lot of n—– outside the door … Everybody has their time in this shit, and when motherfuckers had their time, it wasn’t mine. But now it’s mine.”

To reiterate, that time was a decade-plus in the making. Gibbs nearly gave up post-Interscope. But Lambo and the late Josh the Goon, an engineer and dear friend who sacrificed money, his couch, and his kitchen for Gibbs, encouraged him to grind independently in L.A. In the thick of the blog era, Gibbs became a critical darling, eventually landing New Yorker and New York Times acclaim for projects like The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs (2009) and Str8 Killa (2010) and winding up on the aforementioned 2010 XXL Freshman cover. Fellow freshmen like J. Cole, Big Sean, and Wiz Khalifa would blow up soon after, but Gibbs refused record contracts, instead verbally aligning himself with Young Jeezy’s CTE World. Their eventual and highly publicized fallout bled into the creation of 2014’s Piñata, Gibbs’ first album with Madlib, the Oxnard-bred loop-digger and alchemist capable of turning collages of obscure samples into neck-snapping yet emotive beats.

[embedded content][embedded content]

On Piñata, Gibbs used his Bo Jackson-like versatility to attack Madlib’s unquantized, unpredictable, and avant-garde beats with dexterity and unfathomable ease. If prior Gibbs projects had been excellent albeit lower budget street flicks, Piñata was elevated arthouse cinema, Gangsta Gibbs brought to you by A24. Now an accepted contemporary hip-hop classic, the album forever altered the trajectory of Gibbs’ (and arguably Madlib’s) career. Gibbs argues it changed the course of rap.

“When I made [Piñata] … I feel like I made bars matter again,” he says. “[Piñata] opened me up to a different audience because it was Madlib. Then you had them little Madlib n—– that didn’t even pay attention to me before like, ‘Oh shit, Freddie Gibbs!’ And then you had some of them that was like, ‘This isn’t MF DOOM.’ So the fuck what? You’re goddamn right it ain’t. MF DOOM can’t do this shit. Rest in peace, no disrespect.”

In the two years after Piñata, Gibbs toured the globe with Madlib, survived an attempted shooting, had his first daughter, kicked a nagging lean habit, and released 2015’s Shadow of Doubt, perhaps his most commercially-minded release before $$$. To Gibbs and most of the world, it appeared he’d finally been dealt a few winning hands. Then, while touring Shadow of Doubt in Europe in the summer of 2016, his entire life went bust.

Arrested in Toulouse on charges of sexual assault — the alleged incident ostensibly took place after a Gibbs show in Vienna nearly a year before — Gibbs spent months in prisons both in Toulouse and Vienna, spending massive sums on legal fees and short-term rentals. DNA evidence and timestamped selfies eventually exonerated him, but the lingering trauma of nights spent in harrowing European jails remained alongside the damage to his reputation.

“I thought my career was done after that. Usually, a rapper goes to jail and they’re like, ‘Free brodie.’ It’s a badge of honor. For the situation I went to jail in, it was a black eye,” Gibbs says solemnly. “Getting out of that and recovering from that and being here right now, it’s a testament to my perseverance. I could’ve quit when I got out of jail. I could’ve said, ‘I don’t want to rap anymore because people are talking shit about me.’ That was the lowest I had to pick myself up from, but I wasn’t going to let it stop me.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

For the next few years, Gibbs channeled his energies into rebuilding. Between 2017 and 2020, he recorded four projects, the next arguably better than its predecessor. Bandana (2019), his second album with Madlib was, once again, a critical smash and artistic step forward. Within a year, he followed with Alfredo, the Alchemist-scored album that earned him a 2021 Grammy nomination. At the top of the pandemic, though, Gibbs took a break to star in his first feature film. There was more he needed to get off his chest.

Down with the King (2021), which premiered at Cannes, is semi-autobiographical. Gibbs plays Money Merc, an esteemed gangster rapper who’s become disillusioned with recording and the industry pressure to pump out more music. Merc rents a cabin in the woods to work on his next album, but he spends more time befriending the locals, herding and slaughtering livestock, and chopping wood. It’s a quiet and slow film, but Gibbs fills the silences with both palpable frustration and understated pensiveness. You can see the fatigue on his face, feel the weight his character carries. While the film didn’t receive rapturous praise, The New York Times gave it a largely positive review. Gibbs, who had essentially prepared for the role his entire career, claims Merc’s predicament and mental state mirrored his exactly. The film was cathartic for those reasons, but it also assuaged other stresses.

“When I was making Down With the King, there was a lot of shit going on. I can’t really talk about the shit in the streets that was going on, but I had a baby on the way. When I was filming Down With the King, every day on set, my baby mama was on the verge of being in labor. It was intense,” Gibbs says. “I had to leave set and go to the baby’s birth, but I couldn’t go in because only one person was allowed in during COVID, and then my baby mama caught COVID. She was on a respirator and almost died. That was a real stressful ass time, so I just took all of that and put it into the role the same way I do with the music.”

After filming wrapped, there was still the matter of finishing $$$. Gibbs initially struggled. The pressure of turning in his major label debut, a moment so long-delayed and discussed, got to him.

“[I felt] pressure like a motherfucker. Pressure that I couldn’t sell, pressure that I couldn’t make a song that could be on the radio. I didn’t know if I could do that,” he explains. “I just knew I could make great songs. That took the pressure off. I was like, ‘I can make great songs, I have stop bringing myself into something that someone else wants me to do.’”

$$$ songs work individually, but the album’s best experienced in totality. Gibbs, Denton, Lambo, and company arranged the project to flow as one continuous track. If you play $$$on shuffle or skip around, you’ll miss the deft transitions, the nuanced and intentional highs and lows.

“I think people should really sit with the album and not try to review it in a day. Give it a week, give it a couple days. Sit with the shit and listen to it. Quit trying to make everything so fast food,” Gibbs says, his voice filled with the same irritation he brought to Money Merc on screen. “That’s why everybody keep putting out this music at high rates. They feel like we’re not giving them enough recognition for the music they’re putting out, but most n—– put out trash. I’m giving you another classic. I set the standard for myself when I made albums like Piñata, Bandana, and Alfredo. I’m not going to go down from there.”

Gibbs says all of the above while draining the remains of his third Hennessy sidecar. When asked about his next professional ventures, he mentions several movie roles he’s lined up for next year and an imminent $$$ tour. But there are no titles, no dates of any kind. He knows the value of the cards in his hand. He always has.

“The tour is going to come, and it’s going to come with a vengeance.” He pauses for a moment. Then the endearing antihero delivers a punchline for those following his latest rap beef: “And it’s not going to get canceled.”

For now, until he steps on set or on stage again, Gibbs is focused on three things.

“Being a good father, being a good boyfriend,” he says. “Being an asshole.”

Leave a comment