John F. Kennedy once pondered: “What’s the use of being Irish if the world doesn’t break your heart?” The Irish interpretation might be: Feel and live every moment, and don’t go down without kicking and screaming.

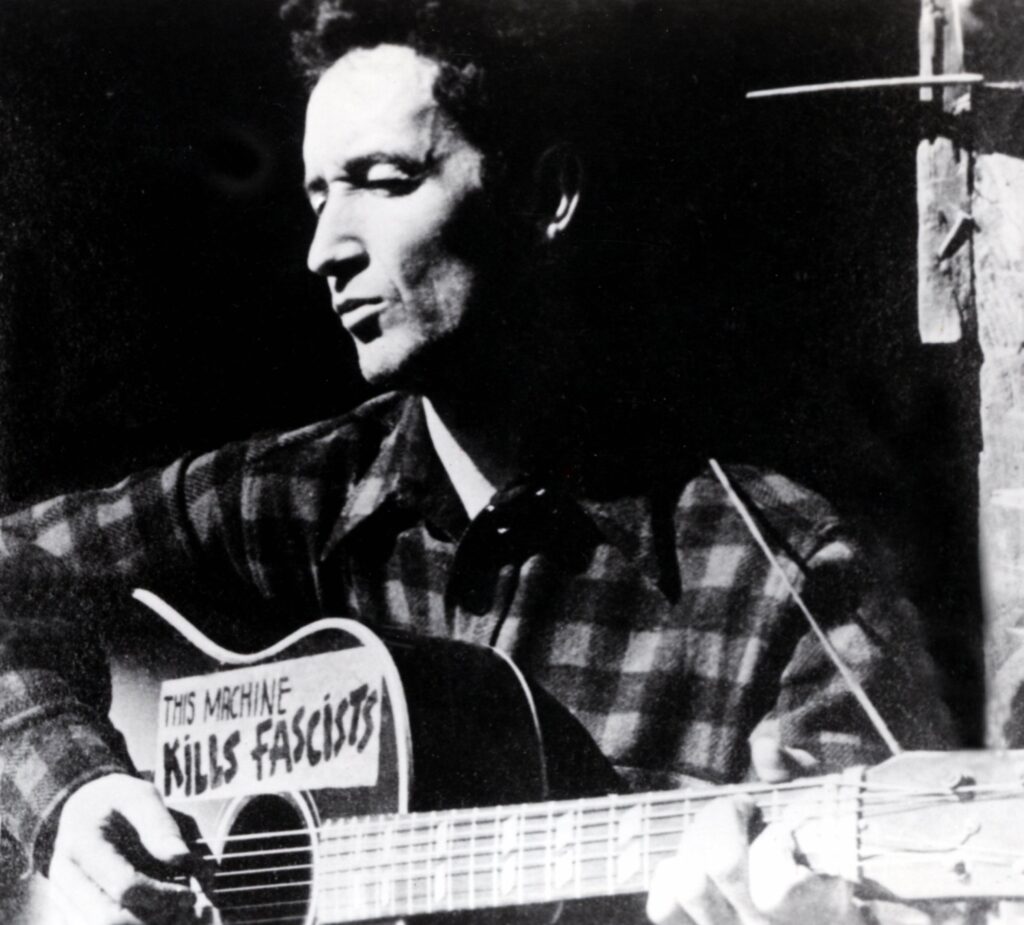

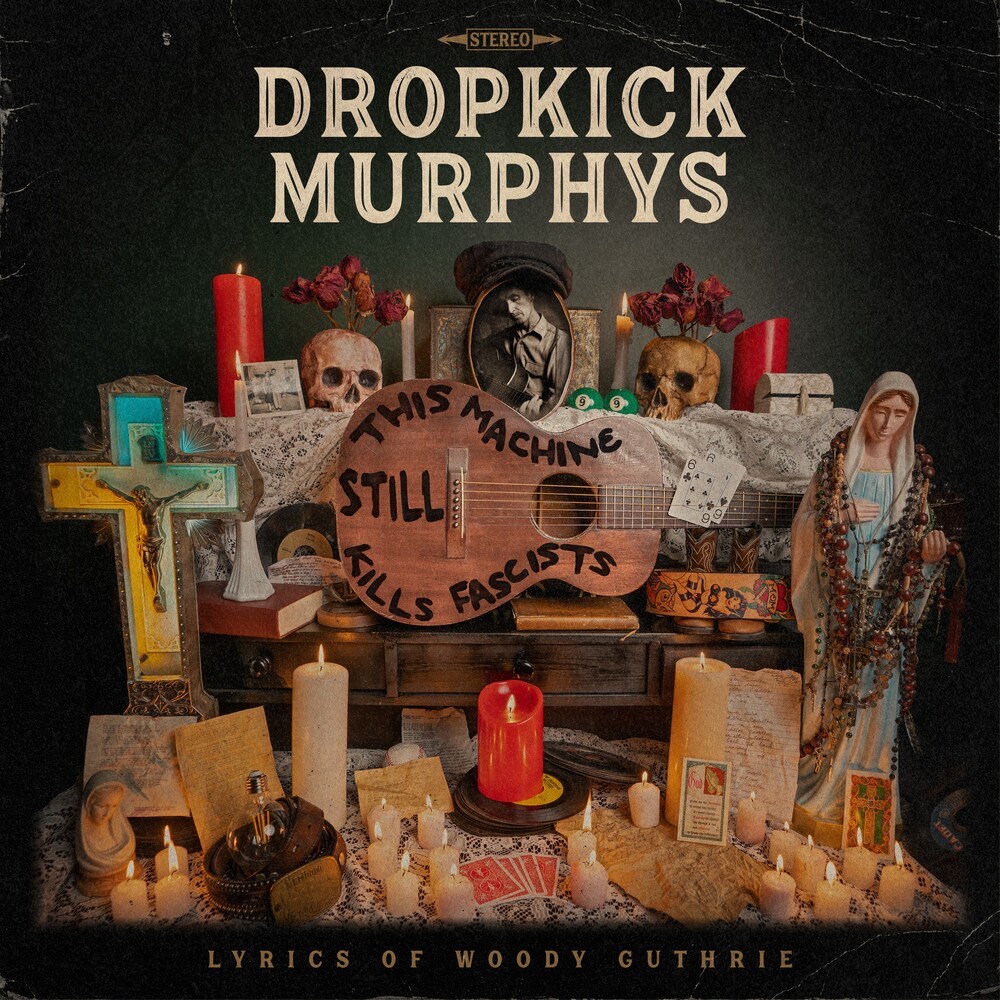

Since becoming a band in 1996, Boston-based Celtic punks Dropkick Murphys have made a career out of kicking and screaming — with purpose, message and rollicking melody. Their new album, This Machine Still Kills Fascists (out September 30), is a continuation of their unique collaboration with Woody Guthrie, who, before passing away in 1967 at 55 from a long battle with Huntington’s Disease, left behind hundreds of unproduced and unfinished songs, meticulously preserved by The Woody Guthrie Foundation. One of his eight children, 72-year-old daughter, Nora Guthrie, is the foundation’s president, who connects her father’s meticulously archived lyrics with the bands who give them new life.

“Why in the world is this white-haired grandma doing interviews for a punk rock band? Am I going to ruin their career?” laughs Nora Guthrie, her freestyled silver curls draped naturally over her shoulders. For the real inside joke, we have to go back to the earlier 2000s, when Dropkick Murphys founder and frontman Ken Casey got “the call” (the calling?) to come and collab with Woody beyond the grave. You can’t just go to the archives, digging around like it’s some yard sale. You have to be invited. Nora’s son Cole had a band poster hanging in his room, told his mom they were cool. She liked their music and vibe.

According to Nora, her father wrote over 3,000 partial lyrics and songs — remarkable for any musician, but even more when you consider Woody’s health was in steady decline by his 30s (Huntington’s degenerates brain function). Regarding those lyrics, also according to Nora: “They’re not all good. Some of them are really stupid, and some of them are great.” She describes an early meeting when Ken Casey “picked the stupidest song that my father ever wrote. It was scrawled on a little piece of yellow paper, legal pad…”

It was called “Shipping Up to Boston.”

Nora recalls: “I went, like, ‘Oh, my God, what a stupid lyric. What in the hell?’ It has the word Boston in it…I went like, ‘Okay, Ken, whatever.’” She laughs some more. Of course, once DKM had set Woody’s lyrics to their signature sound, it eventually went on to become their platinum-selling single, also featured in the 2006 Martin Scorsese film, The Departed. “That became the theme song for the Boston Red Sox,” Nora says, thoroughly convinced that the band, in her mind, on some metaphysical level, helped the team break their 86-year World Series losing streak in 2004, the year of the song’s original release. “They put out ‘Shipping Up to Boston’ and [the Red Sox] win the World Series,” she says.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Even more, she thinks that Ken and the band have a special connection to Woody and his message. So when Ken called and said he wanted to make a whole album — eventually titled This Machine Still Kills Fascists, a riff off of the message scrawled on her dad’s guitar — her response was: “Whatever you want, Ken.”

Nora compares Casey to a mystic. “When Ken does a Woody song, things happen,” she says, wondering what the album’s release will consequently release in the world around it. “Well, there’s one called, ‘Waters are Rising.’ Oh, have you heard about any flooding lately? Oh, yes. Hello, Georgia. Hello, Rhode Island. It’s just like this weird connection that [Ken] has.”

Clearly, in order for her father’s lyrics to carry on in this way, Woody had that connection, too — a deep connection to the people, times and culture — and the need to write and sing songs about it. “There is something bigger than the man happening,” Nora says about her dad, pointing to an article about billionaires buying up countless acres of land in Montana and Wyoming. She refers to her father’s most famous folk song, “This Land Is Your Land,” penned in 1940 in Midtown Manhattan when he was only 27.

“That was my dad’s line: ‘And this land is your land. I roamed and rambled and on this sign, it said, ‘No trespassing,’” she says. “Then my father wrote, ‘But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing. That side was made for you and me.’”

Nora notes two musicians during the ‘50s and ‘60s devoted to carrying on Woody’s songs and purpose. The first, Pete Seeger — “like a puppy dog to my dad” — dropped out of Harvard to become a folk singer and follow Guthrie around the country. When Woody got sick, it was Pete who sang Woody’s songs. And then, in 1961, someone showed up at the house looking for Woody, a 20-year-old troubadour named Bob Dylan.

“Bob used to go out to the hospital and help take care of him, actually,” Nora recalls. “He was a very beautiful young man then. If my father needed cigarettes or writing pads or pencils, he would bring stuff out to him and visit him in the hospital. It was really those two people that broke Woody out of a very small group of folk people in the [New York’s Greenwich] Village in 1940. There were like 20 people who were interested in folk music, and Pete and Bob did the rest.”

Now, when it comes to connecting Woody with other musicians, she steps out of the way, acknowledging that not every process is the same. In some cases, the time was right and the artist was at the ready, as with Woody’s song “Beach Haven Ain’t My Home!” Woody’s family lived in a Brooklyn complex called Beach Haven, owned and operated by Fred Trump. “My dad found out when we were living there, in this apartment, that they were turning away Black families and he wrote songs about it,” Nora tells me. The song — also titled “Old Man Trump” — was recorded by Ryan Harvey (with Ani DiFranco and Tom Morello) and released in 2016 using Woody’s 1950 lyrics:

Beach Haven is Trump’s Tower

Where no Black folks come to roam,

No, no, Old Man Trump!

Old Beach Haven ain’t my home!

“Sometimes, I instigate the connection between the material world and the other world,” Nora says. Being Woody Guthrie’s daughter, peaceful protests are in her blood. She feels it’s in Ken Casey’s blood too. “They want to be where the trouble’s at,” she says of Dropkick Murphys.

“I’ll look at a lyric [of Woody’s] and I’m like, ‘I cannot see a folk singer doing this lyric. No, this is a screaming lyric.’

“This isn’t your ‘Kumbaya’ moment. This is a Dropkick moment.”

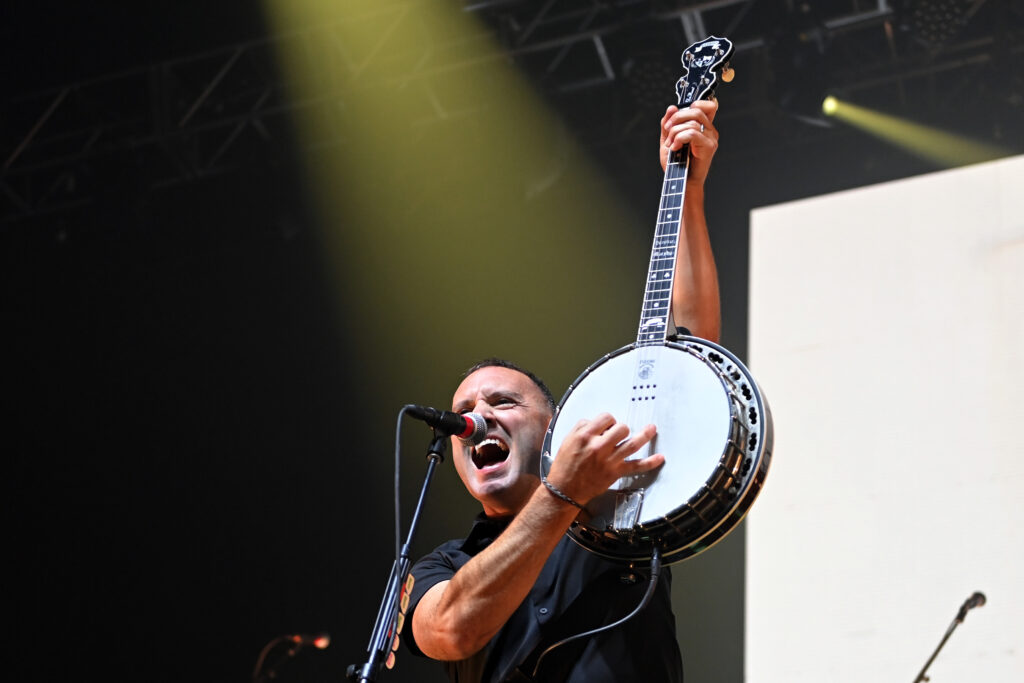

Ken Casey and I catch up after he’s settled at home in Boston from DKM’s recent jaunt in Europe, enjoying the last throes of New England summer. We meet just days before the band released their second single from the new album, “All You Fonies,” and a few days after I’ve spoken with Nora. “I’m lucky to be loved by her,” Ken says, recalling their first meeting 20 years ago, the feeling of knowing Nora “forever” and the “freedom and autonomy” that launched their unique working relationship. He recalls getting the first call from The Woody Guthrie Foundation to come visit and view Woody’s lyrics as mind-blowing as when asked by the Red Sox to perform during their 2004 World Series.

“It’s like…whoa,” Ken says.

Wide-eyed, holding his hands side by side and face up, he reenacts the literal white-gloved process of handling Woody’s lyrics so gingerly the attendant at the Foundation joked he’d need to be more careful. “I felt like I had precious cargo in my hands,” he says. “We understood the importance of what we were doing. I think Nora understood that we understood, and that’s what took all the pressure off.” The alignment with Woody was instant and so strong that they even joked that Ken could be Woody reincarnated. “When I went to his hometown of Okemah [in Oklahoma], I actually had this creepy feeling I had been there before, and I said, ‘What’s the potential I could be reincarnated and could be your father?’ I don’t know whether it’s because I’m so passionate about the topics or what. For me, that made the whole project seem just so fun and intense. Every feeling involved with making a record felt heightened for this.”

“Fun and intense” is the perfect way to describe This Machine Still Kills Fascists, but with a special dose of piss and vinegar that can only come from a deep-routed mission. Ken calls it “fire and passion,” particularly surrounding issues of unionization and solidarity amongst workers.

He says the timing is right for This Machine Still Kills Fascists — in more ways than one.

“A lot of these things he was singing about have come back around to roost. To make an important album, it first has to be important in your heart. There has to be a motivation. We were very motivated to make this album now because we felt like his words need to be sung. Like one of the songs on the record, “Ten Times More” — it has to be sung 10 times more and 10 times louder for anyone to hear it over the noise that the other people are creating right now.

“I think there’s a tendency with people that share my beliefs that good will prevail over evil or whatever. That things will work themselves out. I don’t think that’s necessarily the case unless people stand up. A lot of people think, like, ‘Well, we’ll take the high road, let them take the low road.’ Sometimes when they go low, you got to go lower. That’s where I’m at now, anyway.”

The timing was also right for the band to make the album acoustic, the way only DKM can do it. “We wanted to make it Dropkick Murphys; we wanted to bring it to life, but part of the reason we did the whole album as acoustic is we did want to retain some of Woody’s flavor,” Casey explains. “I doubt that he probably would have written the music the way we did, but at least it has that nod to him.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

For anyone who feels music has no place in politics — there’s no room for negotiation here. “I feel like it’s potentially life and death to democracy,” Ken says, noting he’s always been attracted to music with a rebellious spirit.

And if you feel the urge to tell them to “shut up and sing,” don’t bother.

Ken says: “I think it’s pretty amazing that people think you’re that one-dimensional of a human being. What am I? A parrot? Shut up and sing. Shut up and talk. It doesn’t make sense.

“There’s plenty of music out there to listen to, if you don’t like what we say. I think our politics have always been pretty obvious from the start. Our first album was heavily political about the middle class and the working class being stepped on and their place in society starting to crumble. Fast forward 25 years, and I would say that the other side has been pretty successful with a lot of union-busting and a lot of getting the working class to bicker amongst themselves. We’re all arguing about left wing/right wing while they’re just passing another tax cut for the rich.

“I think that’s exactly how those people in power want it, that we take our focus off of what’s really happening and fight amongst each other so they can get away with the real crimes a lot easier.”

Naturally, for Casey, the process of working with Woody’s lyrics is thinking about how Woody was feeling at the exact time he wrote them.

“There’s a bit of the mystery that these lyrics exist,” he says. “You know what he’s saying, but you wonder what was the actual inspiration — whether it was his finished, typed-out version or some of the poorly-written, jotted-down notes that he was probably writing on his knee somewhere. He would always date it, which was amazing that he thought to do that because fast forward all these years, the difference between a song written in 1939 and 1952, there’s a lot of changes in that time. It gives you a little clarity.” Woody sometimes noted his actual location, as well as a little anecdote about the song to give it all context. When Ken read through the lyrics, he’d sometimes get hit instantly with a melody. Sometimes the penmanship required deciphering. Others felt like incomplete thoughts, something Ken learned to embrace.

“Ironically, usually for Dropkick Murphys, the music comes after a vocal melody, so it’s very rare that Dropkick Murphys has a finished, complete musical song,” he says. “We did for ‘Shipping Up to Boston,’ and had I finished the lyrics for that, I know I would have filled all that space with words. The beauty of that song is how spacious it is. The words are the words, and they hit when they hit, but then there’s a lot of space to build to it. The minute I looked at those words, I said, ‘Oh, those go in the song we already have.’ It was like…boom.

Nora’s son Cole — whose DKM poster was hanging on his bedroom wall decades ago — plays on the album. The final track, “Dig a Hole,” features a rare recording of Woody’s voice. “I’m doing backup vocals on the song, and there’s a group of us in the room, and [Cole’s] right beside me, and you’re hearing Woody’s voice along with us, and you seeing him out of the corner of your eye. It was just goosebumps. It was a perfect way to end the record, to have it end with hearing Woody’s voice. For me, that gives me chills.”

On their upcoming tour (kicking off October 20 in Concord, New Hampshire), the band will be giving some of their older songs the same “Americana twist,” as Ken puts it. “It’s been really fun to rework some of the songs,” he says, ensuring that their audience will still get the fiery experience that makes them a legendary live band. “It’s not like people are going to come and say, ‘What the fuck is this? I don’t even recognize this song,’ but you’re going to get‘Shipping Up to Boston’ with a harmonica instead of a tin whistle and things like that.

“Yes, Americana and Celtic music are very close cousins.”

Leave a comment