This week marks the 53rd anniversary of Woodstock — the music and art fair of 1969, originally announced as “An Aquarian Exposition,” which took place at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, New York, after promoters couldn’t find a festival location in the town of Woodstock itself, a well-known haven for musicians at the time.

I always think about Woodstock in August, because I was there.

In 1969, I was 15 years old and my progressive parents (read: smart, but drug addled) bought me and my twin brother tickets for what would miraculously turn out to be an experience that unfolded in exactly the same way it was promised: 3 Days of Peace & Music.

Could there have been other parents like my parents (is it even possible to imagine anybody can be like anybody else’s parents?) who actually bought tickets to Woodstock because…who knew it would become the thing that felt bigger than the world? For something that big, it feels like nobody should need a ticket. And that first day, as if by divine intervention, no ticket was needed, thanks to the crowd of us knocking over the protective fence down and then, master of ceremonies Chip Monck, announcing within minutes over the loudspeaker: “It’s a free concert from now on. But what it means is that these people have it in their heads that your welfare is a hell of a lot more important…than a dollar.”

To my mind, that announcement changed everything. It marked the beginning of recognizing something beyond us, turning almost half a million people into the impossible — a community small enough to be able to hear and respond to announcements being read over a loudspeaker. We were huge, but we were local. This wasn’t quite the same realization 30 years later.

I recently watched the Netflix documentary, Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99, which isn’t about a train wreck, but a people-wreck, where the safety of human beings was certainly not a major concern for the promoters who were hoping to strike lightning a third time, just five years after Woodstock ‘94. At the ’99 Woodstock, there was some music, but certainly no peace. Hundreds of people were complaining about vendors running out of the overly-priced food and water. Rapes and other forms of sexual assault were reported. Violence erupted in various pockets of crazies towards the end, mostly aimed at dismantling the stage and its surroundings. And if that weren’t enough, scattered fires erupted across the whole expanse of what had been a decommissioned military base in Rome, New York, about three hours north of the original Woodstock site. Griffiss Air Force Base looked like a war zone, and the seemingly mostly white male population glared into cameras like ravaged zombies who were dancing wildly on the edge of the apocalypse.

What gave the first Woodstock its renown was the simple fact that it was, above everything else, a first. Any first is extraordinary and you claim it as either an object of devotion or ruin: first kiss, first death, first real anything. We were so many people having the same outer experience in real time that, I think, for many of us, the entire encounter was suffused with the spirit of Joni Mitchell’s prescient advice to get ourselves back to the garden.

When had any of us seen this much humanity come together for a common cause outside of marching that year and the year before against the war in Vietnam? Woodstock confirmed that music itself, along with all the protests in the streets, was the conduit through which we, the counterculture, were being taught to listen to in the first place. And to rise up against the machine, the establishment’s way of doing things, which clearly wasn’t working.

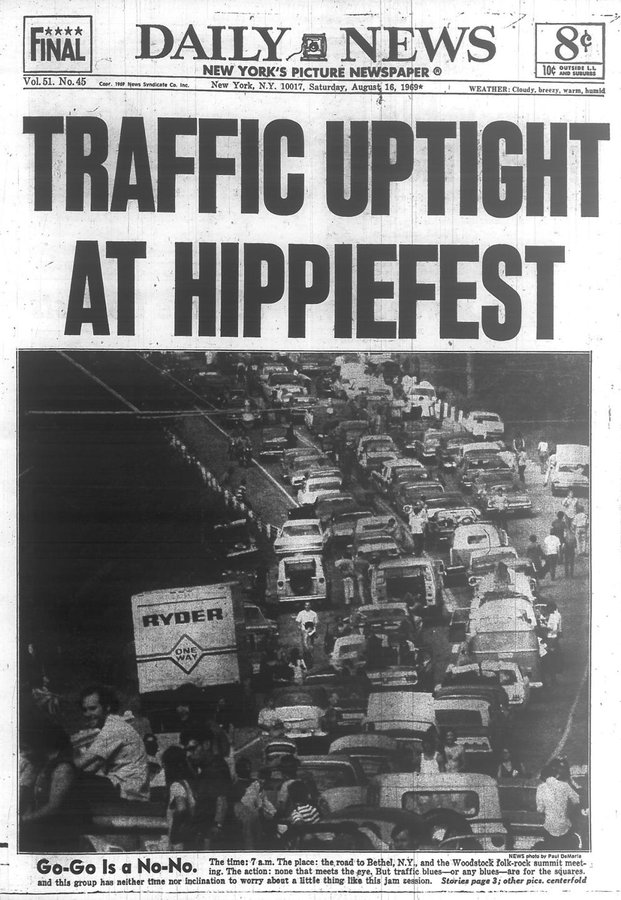

Music itself was responsible for an eight-hour delay on the New York Thruway between New York City and the concert site, causing the New York Daily News to proclaim on its Aug. 16 front page: TRAFFIC UPTIGHT AT HIPPIE FEST. The roster of performers at that 32-act hippie fest was extraordinary and some of them, I’m sure, were hippies themselves: Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin (hippie), Joan Baez, Incredible String Band (the hippest of the hippies), Ravi Shankar, Arlo Guthrie, Santana and The Grateful Dead (hippies), just to name a few. But how many acts did anybody really manage to sit through? I think we may have seen three or four whole sets.

There are so many different ways of being with other people when you are making history, especially when you have just lived through the previous year’s history-making murders of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy — assassinations that underlined the atrocious and astonishing fact that our peacekeepers were somehow the threat and not the solution to living in peace.

Woodstock was about the music and it wasn’t about the music.

It was about people who had tickets and people who didn’t have tickets. (And then it was about the people who didn’t have tickets.)

It was about a new friend named Licorice crawling out of her tent at 7:00 a.m. on the second day and shouting, “Does anyone have any dope to smoke?”

It was about the response of five different male and female voices saying, “Over here, over here, over here, over here, over here.” And not one person saying, no.

It was about nobody saying no to anything except the rain for four days.

It was about Swami Satchidananda coming out to bless us and the event.

It was about the artisans with their crafts setting up little shops in the woods that seemed to appear only at night in a grove I couldn’t find a second time and lit up by tiny lights in the branches.

It was about those-were-the-days of the VW bus. And the couple on the third night who were braided together in a sleeping bag underneath the VW bus and my brother pissing on them because it was too dark to see them sleeping there.

It was about not remembering money.

It was about the rains and the rains and the rains that came on Aug. 17. And then it was about the mudslides.

It was about searching and finding the people we were looking for.

It was about the first time in so many lifetimes that what was happening held the kind of power we were certain was enough to rock the world. Rock steady.

It was about the fact that there was only one general store within walking distance and it ran out of supplies before Ritchie Havens’ opening act was finished.

It was about the drugs everywhere and how the drugs seemed to relax the crowd into all of us having almost the same high until I didn’t hear one argument for the entire time I was there.

It was about the almost otherworldly beauty of naked men and women covered in grey mud and yellow flowers singing in a nearby pond.

It was about the watermelon truck we saw whizz by and, as if, by sheer collective will, a few dozen watermelons rolled off the truck into the road.

It was about the stranger from Little Rock, Arkansas, who had a jug of Thorazine for people who were having a bad trip.

It was about Chip Monck again, announcing to steer clear of the brown acid because it wasn’t any good. And about the announcement, “Helen Savage, please call your father at the Motel Glory in Woodridge.”

It was about being lucky enough to be fed brown rice and honey by the Hog Farm and camping out next to The Merry Pranksters, even if Ken Kesey wasn’t with them that trip.

It was about watching Joan Baez rehearsing on the stage at 4:00 a.m. while only about 30 of us were awake and we were all very quiet standing there in the field of sleeping co-conspirators.

Woodstock was about the music and it wasn’t about the music.

Michael Wadleigh’s Oscar-winning documentary of the original Woodstock really does capture the authenticity of what happened there and perfectly documents a lot of what occurred behind the scenes. And then, of course, there’s Joni Mitchell’s namesake anthem, “Woodstock,” written in absentia, which sees the whole experience in the context of being a mega-celebration by a counterculture resolutely poised against violence, where “the bombers riding shotgun in the sky and they were turning into butterflies above our nation.”

I know for me, and I would hope for a lot of us who were there and ended up falling into whatever dream state we ended up falling in (sleeping under the stars or a VW bus, mud dancing in the rain, meditating, or listening to so many different strands of music in the middle of a dairy farm in upstate New York), that some gratitude arises for that when-we-were-hippies August; gratitude for being given the immense, but somehow still secret place to hear all that music. That music, and in such a stardust time, was the best thing about being alive in America.

Leave a comment