This article originally appeared in the March 1998 issue of SPIN. It is being republished in honor of the 25th anniversary of South Park.

Here’s how it works in the post-Simpsons era. The tremors start at coffee shops, movie queues, dorm rooms: young people talking in bizarre pinched voices. Goateed cashiers spouting off-color catchphrases. Strange little icons on T-shirts and screen savers. Then, the Web sites spring up. The upstart network flourishes. The single is released. The movie is announced. Suddenly, before you know it, we’re up to our bungholes in ’90s cartoon Zeitgeist.

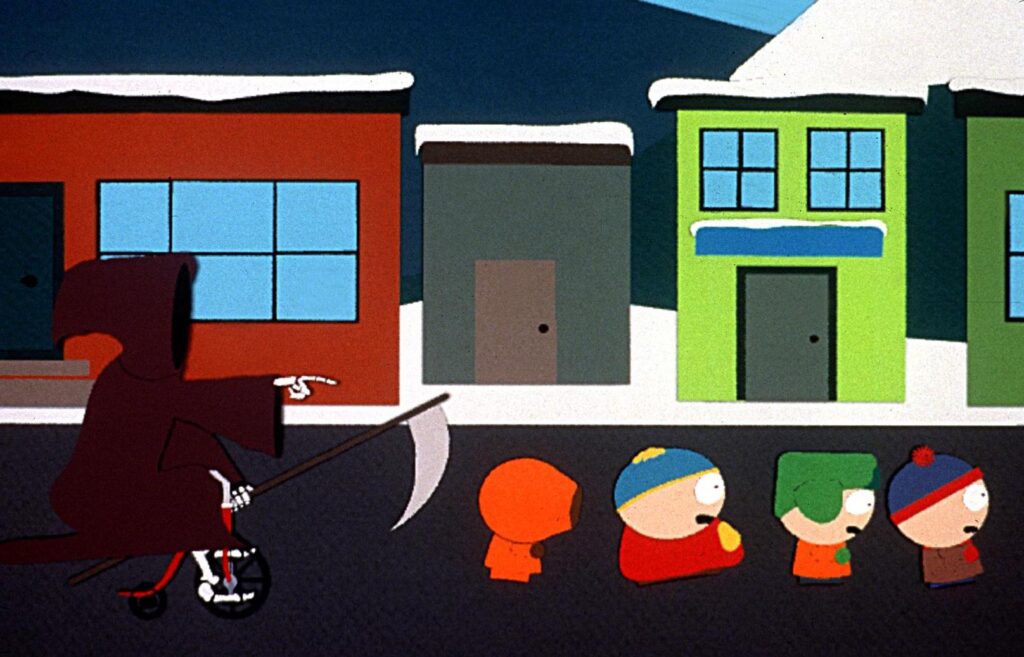

With the unstoppable force of a dead-Chris Farley joke, Comedy Central’s sick, crudely animated half-hour show South Park—featuring the adventures of four gimlet-eyed, foul-mouthed third-graders—has become not just the hottest cartoon but the hottest youth-cult phenomenon in the country. Like Bart and Butt-head before them, the construction-paper-hewn Stan Marsh, Kyle Broslofskyi, Eric Cartman, and the permanently hooded Kenny McCormic now rule the malls of America. Their likenesses are everywhere, including on last year’s hottest-selling T-shirt (“We have merchandisers lined up around the block!” boasts Comedy Central spokesman Tony Fox). Their signature lines—”Kick ass!” “Omigod, they killed Kenny”—are on the lips of paperboys and grad students across the nation. They’ve even impressed the critics. Next to “such popular agents of murder and mayhem” as South Park‘s “cackling characters,” observes the New York Times‘s Michiko Kakutani, “the Devil doesn’t even stick out.”

Industry seismologists measure fan ardor more directly. “CNN has to have a worldwide disaster to come up with a 1.4 [rating],” said one television industry consultant. For its Christmas show, South Park earned itself a 5.4 rating, the highest for an original series in Comedy Central’s history; 4.5 million people tuned in, more than seven times Comedy Central’s average. Rights to a South Park soundtrack album, currently in the works, have a rumored price of $2 million. Meanwhile, showbiz giants from Jay Leno to Jason Priestley to George Clooney have either offered or given the show subliminal voice cameos—the last performing the woofs of a gay dog.

All of this—plus a feature-length film and the inevitable consumer effluvia (mugs, boxer shorts, beach towels, backpacks)—comes on the strength of just a handful of episodes. Gen-X college roommates Trey Parker and Matt Stone hit the motherlode of goofball hip with one alarmingly simple idea: Take a bunch of cute li’l quaintly animated characters—redolent of early-’70s instructional films and Peanuts holiday specials—and slam them into ’90s grossness and dread. Somehow, by featuring vomiting, farting. racial slurs, and decapitations, their not particularly high-minded creative enterprise seized pole position in the culture industry. Somehow, South Park must speak to some hunger deep within us, must reaffirm some basic truths about humanity. That, or we’re truly a nation of retards.

“There is no more direct and accurate way of finding out what is really on a people’s collective mind,” writes Alan Dundes in his book Cracking Jokes, “than by paying attention to precisely what is making the people laugh.” To that end we turn to 1996’s “The Spirit of Christmas,” the $750 video Hallmark that launched South Park. In “Christmas,” Parker and Stone introduced the four snowsuited characters and their perpetually wintry milieu, had them quarrel and bait the Jewish Kyle and hurl fat jokes at the rotund Cartman, and brought in the off-color surrealism that would become a South Park trademark. In flowing robes, Jesus appears before the kids saying he has arrived to avenge the despoiling of his name by Santa Claus. (“Don’t say ‘pigfucker’ in front of Jesus,” Stan admonishes Cartman.) Jesus begins a Mortal Kombat–style kung fu duel with his arch-nemesis “Kringle” while the kids fret over whom to root for. All the elements were in place: sadism, sacrilege, and nonstop profanity.

After the furiously circulated video led to a deal with Comedy Central, South Park debuted to flesh out the four kids’ world. Early episodes introduced us to the priapic school Chef (voiced by Isaac Hayes), the schoolteacher Mr. Garrison and his hand-puppet/id Mr. Hat, Wendy Testaburger (whose presence makes the love-struck Stan vomit), and other town folk. As in “The Spirit of Christmas,” all the characters remained jittery composites of cut-up paper shapes whose eyes blinked and teeth gnashed in distant approximations of facial expressions.

With a built-in audience of the tens of thousands who had seen the Xmas bootleg, South Park was an instant hit—especially among snickering white pubescents. Elektra Records’ Brian Cohen, responsible for purchasing TV commercial time for the label, knew the show was made-to-order for advertising the likes of Pantera, Metallica, and AC/DC. “You go to the concerts and you see a lot of young boys who are ready to, you know, cut something and make it bleed,” he says. “It was pretty clear that this was the right audience.”

But while the show works brilliantly as a cult hit, it makes a curious transfer to the larger culture. Unlike comic sensations of yore—Monty Python, say, or Firesign Theater—you don’t sound like a soigné aficionado of fine comedy when you repeat South Park sound bites at school: You sound Special Ed. And while there is enough splenetic wit and manic detail to generate obsessive fandom (entire sections of Web sites are dedicated to deciphering just what Kenny is mumbling), subjects like alien abduction, genetic engineering, and Kathie Lee are hardly original targets for satire. South Park fares well in comparison to Beavis and Butt-head, but not to its other obvious forebear, The Simpsons. A years-old institution with a full team of writers, The Simpsons is both higher-yield jokewise and more virtuosic, with gags compounding gags and a more coherent sense of the characters’ foibles and predilections. The Simpsons and its follow-on King of the Hill also undertake a broader critique of suburbia, mass media, family life, and beer-swilling fat guys than does South Park. South Park‘s more about puking and aliens and stuff.

In a sense, though, that’s the point. South Park is a punk-rock Simpsons: not as droll nor as well-executed, but faster, cruder, with fewer characters and less ambition. Not only is there a firm grasp of early punk’s nihilistic juvenilia—Cartman’s Hitler Halloween costume was positively Ramonesian in its gleeful bad taste—but South Park also shares punk’s slapdash production values. Turnaround time per episode is lightning-fast—once every three weeks—which makes it the most shoot-from-the-hip comedy program on television.

Like many subcultural crazes, the show’s appeal is about style and form more than content. Cartman’s voice—a trebly, gravelly mix of Truman Capote and Wolfman Jack—is alone worth the price of basic cable. And, at its most elemental, South Park is founded on a sight gag with legs. Of the evergreen comic tropes out there—men in dresses, talking computers, vice presidents—one of the most dependable is the dismembering of cute little moppets. (Witness Saturday Night Live‘s immensely popular “Mr. Bill” series.) The central irony is that, for all its absurdity, South Park is probably truer to the kid experience than any other program on TV. It has the familiar sadism, the shameless greed, and the exuberant curiosity—in spades. Perversely, South Park may be one of realest social worlds on TV.

But much like childhood itself, South Park isn’t a franchise that’s built to last. Even by the sixth episode, “Death,” Parker and Stone were already making none-too-subtle allusions to crass TV shows “that have come and gone that have been very bad [and usually] get taken right off the air.” Maybe, as the creators themselves seem to recognize, this wouldn’t be such a terrible thing.

Will South Park linger ignobly like Roseanne and the Rolling Stones, cashing checks while tarnishing its luster? Or will it—as the recent sub-sub-lowbrow Christmas episode suggests—go out in a blaze of talking poo? South Park‘s essential comedic device—the clash between childhood innocence and adult puerility—is otherwise known as “junior high,” and everyone graduates sooner or later. With a new movie beckoning and their place in history secured, Parker and Stone may just be savvy enough to sabotage their creation before it turns against them. Even Cartman knows it’s better to gross out than fade away.

The Creators: Cannibalism, Pornography, Mental Disabilities, Et Cetera

Todd Krieger explores the ever-indelicate cultural offerings of Trey Parker and Matt Stone

“Whoever rents this porn,” says Trey Parker as he observes a fake knife plunging into the head of a mostly naked porn star, “is going to be so pissed off.” On a balmy Saturday afternoon in Los Angeles, Parker and fellow South Park creator Matt Stone are relaxing from the rigors of inventing televised entertainment by hosting a weekend porn shoot at their beachfront condo. As the cast and crew move about the house shooting various scenes, Parker and Stone are on hand to contribute a few personal flourishes, including what has to be the most unusual murder scene ever to be filmed in the sex-vid industry: death by tone-poem compendium. That Parker possesses a volume of symphonic poems by the 19th-century German composer Richard Strauss hints that beneath these lowbrow amusements lies a highbrow pedigree; that he and Stone have helped create a film that depicts one naked actor killing another with said book during sex hints that these two culture-makers-of-the-moment are unabashedly weird.

While South Park‘s unexpected success has led to the realization of pubescent fantasies like at-home pornography and “meeting the chick from Species,” the 27-year-old Parker points out that the show has also been an arena for personal growth. ”We explore everything,” he says. “It’s great therapy.” And though Comedy Central has allowed their therapy to explore some fairly unusual territory (see elephant/pig sex, anal probes for the young, etc.), there are limits to what they can air. “The only thing they wouldn’t let us do was make fun of the Nation of Islam,” says Parker. “We think it was out of fear that we’d be killed, and then they wouldn’t have a show.”

Hungry South Park fans will readily eat up the new episodes of their critically acclaimed hit (20 more have been ordered), but it’s the live-action porn industry send-up Orgazmo, slated for a summer release, that may prove to be a truer measure of their talents. Orgazmo stars Parker as Joe Young, a Mormon reluctantly transformed into porn star Captain Orgazmo, and Stone as an overzealous lighting technician. Appearing alongside them are veteran porn actor/cult hero Ron Jeremy, a trio of sex queens espousing a twisted form of girl power (“I am not going to do any ass-licking today”), and a sidekick with a dildo strapped to his head. Yet for Parker and Stone, working in porn is remarkably similar to working on South Park. “The nice thing with the kids is that you can put them in a little bag at the end of the day,” says Parker. And porn stars? “Not much different. They already get fucked and they’re not like, ‘I don’t want to do that, I’ll look s-s-s-s-s-stupid.’ I mean, c’mon, they’ve had anal sex close-ups.”

In January, while Orgazmo was making its U.S. debut at Sundance, Cannibal: The Musical, Parker’s first work as writer/director/star, was premiering at the underground Slamdance Festival. Shot for a minuscule $125,000, Cannibal (billed as a cross between Oklahoma! and Friday the 13th) has begun showing around the country at a series of midnight shows. Audience participation is encouraged in the hopes that it might become the next Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Naturally, Hollywood wants in. Parker’s completed script for a live-action project titled Fuzzies recently drew the attention of producer Scott Rudin. The story revolves around a nine-year-old with a mental disability (he continuously repeats the phrase “bacon and cheese and carrots and peas”) who triumphs over the forces of evil (large “blue-horned fuzzies”) threatening to wreck his hometown. In the film’s climactic scene, a brigade of mentally disabled kids charges over a hill to save the imperiled town from the clutches of the fuzzies. Like previous projects, this one appears to be bizarre and slightly reckless. But Fuzzies—and its estimated budget of $20 million—has been shelved at Parker’s behest. “The only way I could do it is if I left South Park,” says Parker. “They wanted to do it in January. I said no. They freaked out. They’re like, ‘How can you not want to do a Paramount movie?”

Stone and Parker, meanwhile, have taken roles in the next movie from the legendary Zucker brothers (Airplane, The Naked Gun). “We’re part of this ‘baseketball’ team. It’s a combination of basketball and baseball,” explains Stone as the porn crew prepares for another scene in his living room. “It’s about our rise to fame as the sport becomes popular. A lot of what we’re working on comes from what’s happened to us in the past six months and what we’ve been dealing with,” he says, pausing to examine a tube of “hot tamale”–flavored lubricant sitting in front of him. He squeezes a small dab onto his finger and tastes it. “It comes,” he says finally, “from real life.”

The Future?: “Oh My God, They Molested Kenny!”

Its debut season was an instant hit. Now, South Park will face the age-old dilemma: How do you top yourself?

July 4, 1998. Reasserting South Park‘s reputation as the most edgy and eccentric show on television, the launch of the second season is celebrated at a “rave” in a disused San Pedro roller rink, with journalists given directions written on the back of Fat-burger french-fry bags. Hosted by a pointlessly grouchy Janeane Garofalo, the party was “stupid, boring, and pretentious,” Parker and Stone later chortle, but media hype continues unabated. The lone dissenter is New York Times culture critic Michiko Kakutani, who calls the show the “lede equine of the four horsemen of the coming Gen X cultural apocalypse.”

July 8. The first episode of the second season, “Gangsta Gangsta,” airs: After Mr. Garrison gives the class an Ebonics lecture, Cartman and human beatbox Kenny (managed by Kyle), rename themselves “The Notorious P.I.G. and K-III.” Backed by their posse, the South Park Killers, the duo cut a gangsta rap single, “SPK—What Does It Mean?” Even Chef is shocked by lyrics such as “Straight outta South Park, crazy motherfucker named Cartman / Spent my youth anal-probed by an ali-ennn!” Watching his own video at home, Cartman yells to his mom, “Yo, get me some Cheesy Poofs, bitch!” When Kyle’s mother finds her baby son Ike singing the catchy chorus, “South Park, South South Park,” she petitions the Mayor to cancel P.I.G. and K-III’s upcoming performance at the school talent show, but is thwarted by the ACLU. Meanwhile, P.I.G. and K-III fire Kyle as their manager because he’s Jewish. Confused about his musical direction, Cartman vanishes, reappearing for the sold-out concert, unveiling his latest persona—Heavy C—and a new R&B-tinged hip-hop sound: “I say big-boned, you say obese / I’m blowin’ up bigger than Dom DeLuise / Every step I take makes hearts start to break / ‘Cause I’m beefcake, beefcake, beefcake!” An enraged crowd bum-rushes the stage. Outside the school auditorium, Kenny avoids a drive-by shooting, but is tragically cornered by a Kangol-sporting Quentin Tarantino, who attempts to “turn him on” to some obscure Bushwick Bill B-sides.

July 9. Racial activist Al Sharpton joins forces with rappers Fat Joe, Big Punisher, and Biggie Smalls’s mother, Voletta Wallace, to protest the show’s “stereotypical depiction of tragically overweight hip-hop performers.” Prodigy sample Cartman’s voice on their song, “Cheese My Bitch Up” and release an X-rated video in which a topless stripper is pelted with snack treats. The National Organization for Women calls for boycotts of every show on Comedy Central except for reruns of Absolutely Fabulous.

July 13. Wearing “Corporate Cartoons Still Suck” T-shirts, a cranky Parker and Stone appear on an E! network broadcast of the Howard Stern radio show, trashing the “overmerchandised elitism” of The Simpsons and trying to fondle Stern sidekick Robin Quivers.

July 15. Episode 2, “Skinheads, Skinheads, Roly-Poly Skinheads,” airs. On a visit to Denver, Cartman meets some “new friends,” and upon returning to South Park, startles Kyle and Stan with a new look: flight jacket, jackboots, and closely cropped hair. “Hey, Cartman,” says Stan, “you look like Sting!” Meanwhile, Starvin’ Marvin, the Ethiopian child the kids mistakenly adopted through a Sally Struthers commercial, arrives back in town as part of a U.N. conference on the New World Order. Cartman’s new friends also come to town to hold a seminar on “the black helicopters.” When Cartman introduces his new buddies to Kyle, they beat him up because he’s Jewish. “Dude,” a bloodied Kyle says, “those guys are skinheads.” “Fuck you,” replies Cartman, “they’re not skinheads, they’re French.” After the skinheads tag swastikas on the front window of Tom’s Rhinoplasty, the Mayor delivers a hysterical TV warning and asks talk-show host Jerry Springer to speak at a rally against racism. At the rally, Springer tells the crowd about his experiences as a child of Holocaust survivors, but Stan’s Uncle Jimbo and his friend Ned the Vietnam Vet (both militia members) drown him out with gunfire. Chef steps to the microphone and breaks into song: “I have a dream / That one day all of God’s women / Black women and white women / Jewish women and Gentile women / Protestant women and Catholic women / Will be making sweet love / Sweet, sweet love / Yes, I have that dream / Oooh, yes I do / Almost every night.” Chef’s song is interrupted by the skinheads, who have discovered that the tiny African tot is bundled up in a hooded snowsuit. They stomp the first child they see in a hood, only to discover they’ve crippled Kenny.

July 16. The “Skinhead” episode receives Comedy Central’s highest ratings ever (besting even It’s a Paula Poundstone Christmas!). Dogged by paparazzi, Parker and Stone are spotted with David Lynch gulping sugar substitute packets in a darkened corner booth at the Dresden Room.

July 22. Episode 3, “Just Say Nagano” airs: South Park‘s show-within-a-show, Terrance & Phillip, gets a new sponsor, the ultra-sweet candy “Gummi Euphoria.” The kids are excited to try the new confection, but all the local stores are sold out. At a 7-Eleven on the other side of the railroad tracks, Cartman meets up with actor Robert Downey, Jr. “Do you know where we can get some Gummi Euphoria?” asks Cartman. “Sure,” says Downey, handing him some small white pills. Caught with the Euphoria in Mr. Garrison’s class, Cartman learns an important lesson about sharing: “If you want to eat candy in school, you have to bring enough for everybody.” When the principal discovers the class engaged in a group hug/blackout, it’s revealed that Cartman has actually turned the students on to GHB. The Mayor calms the fears of hysterical parents by arresting Robert Downey, Jr., and holds a special press conference, where Downey pitifully apologizes for everything he’s ever done. To keep South Park youth away from pushers, school officials organize an emergency field trip to see the Colorado Avalanche hockey team play the New York Rangers in “the hottest game on ice.” Cartman declares that his favorite Avalanche player is surly goon Claude Lemieux. “Cartman,” protests Kyle, “Claude Lemieux is the biggest cheater in the National Hockey League!” “Screw you, hippie,” says Cartman, “cheating’s cool!” Stan and Kyle’s taunting of the Avalanche’s hapless mascot “Flurry” leads to a melee between players and fans. Lemieux tries to fatally cross-check Kenny, but accidentally renders hockey trophy wife Janet Jones comatose. Chaos reigns. “Dude,” says Stan, “hockey is way better than drugs!” “Yeah,” agrees Cartman. “Violence kicks ass!”

July 23. National Hockey League commissioner Gary Bettman protests the stereotyping of the NHL as overly bloody. “We are the hottest game on ice,” insists Bettman. However, CBC Hockey Night in Canada commentator Don Cherry praises South Park‘s realism. “Finally, somebody on television understands that hockey isn’t for wussies.”

July 29. Episode 4, “Chefs Big Score,” airs: Pursuing a lifelong dream, Chef takes a leave of absence from the cafeteria to try his hand at an R&B career. Mrs. Crabtree, the school bus driver, substitutes in the lunchroom, but the results are disastrous. Salisbury steak is replaced by “Pleistocene pot pie,” and Stan throws up, even when Wendy Testaburger is nowhere in sight. Unable to eat, Cartman begins losing weight rapidly. Meanwhile, “Theme from Chef’ threatens to knock Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind 1998: Song for Sonny Bono” off the top of the charts; its wah-wah-driven chorus is everywhere: “Who’s the kitchen man who’s hotter than a pan? / Chef, whoo, Chef! / Who’s the lunchroom stud who makes female hearts go thud? / Chef, whoo, Chef!” While in L.A. to record a new Free Tibet benefit record, “Monk Aid,” with the Beastie Boys, Steven Seagal, and Carrot Top, Chef is caught in the back of a limo swapping recipes with a transvestite fry cook. His career in a shambles, unable to get booked on even the Keenen Ivory Wayans Show, Chef returns to South Park. Finding the town deserted, he discovers that everyone is at the hospital where Kenny has nearly starved to death, and a vigil is underway for an emaciated Cartman. Chef quickly whips up a Salisbury gravy I.V., saving Cartman, who suddenly begins shouting “Get jiggy with it!” for no particular reason.

July 31. In an effort to rebel against the Hollywood “inspired by” soundtrack formula, postmodern poster-boy DJ Spooky helms an album entitled South Park (Re)mixed, featuring 35 different “sonic musings” on the show’s original theme song. Released by Geffen Records to great fanfare, the album is a critical and commercial embarrassment.

August 3. Nervous about the show’s declining hipness, Comedy Central’s publicity department begins planting false stories in national gossip columns about Parker and Stone’s “secret relationship.”

August 5. Episode 5, “Trial of the Century,” airs: Kenny is found dead in the basement of his parents’ house, apparently strangled and sexually assaulted. “Oh my God,” says Kyle. “They molested Kenny!” Although suspicion immediately centers on Kenny’s family because they’re poor, everyone in South Park is a suspect. A note surfaces demanding a year of free cable, and the penmanship turns out to perfectly match a handwriting sample from Mr. Hat. NYPD Blue detectives Sipowicz and Simone are brought in to interrogate the smart-alecky hand puppet. When Mr. Hat proves uncooperative, Sipowicz slaps him around, which Mr. Garrison appears to enjoy a little too much. “I’m beginning to get a feeling that you and your little puppet friend are in need of some physical therapy,” warns Sipowicz, “and if that’s the case only one of us is going to walk out of this room, and believe me, it’s not going to be Kermit here.” Mr. Garrison quickly gives up Mr. Hat and agrees to testify against him. Mr. Hat brings in Johnnie Cochran as his defense attorney. During the trial, it’s revealed that Kenny’s fatal wound was inflicted anally. “If he doesn’t fit,” declares Cochran, holding up the hand puppet in question, “you must acquit.” “Ooh, that’s gross, dude,” squeaks Kyle.

August 11. Gay activists express outrage at the negative depiction of homosexual hand puppets. “This is the sort of hate-filled environment that has kept Lambchop in the closet for all these long, devastating years,” cries an outraged Shari Lewis in Out magazine.

Late August. Despite Parker and Stone’s erratic behavior and the show’s inability to stir up a decent boycott threat, South Park‘s growing cult success results in a considerable bidding war, and a deal is struck with ABC, the network that had gambled over the years on such taboo-busting series as Soap, NYPD Blue, Nothing Sacred, and Hiller and Diller. But the show’s network premiere is delayed after ABC execs, under pressure from their corporate headmasters at Disney, veto prospective story lines. For instance: Kenny tries to commit suicide via autoerotic crucifixion; Stan gets lured by pedophiles into an Internet child-porn ring; Christian men’s group the Promise Keepers harass the boys’ friend Big Gay Al; Kyle becomes a Lubavitcher Jew; and Chef goes to the Million Man March.

Even when plots gain clearance, the kids’ locker-room chatter is cleaned up drastically. Not only is there no foul language, but Kenny is allowed only a series of easily treatable ailments. One internal memo from a standards and practices exec declares that “if I wanted to hear 22 fucking minutes of bleeps I’d go buy a fucking Orbital record.”

October 1. ABC airs promotional spots for South Park in which Stan and Kyle ice-skate and have a snowball fight in front of a giant network logo, all to a bouncy new theme song penned by the Cardigans.

October 9. The debut ABC episode kicks off as Cartman’s mom remarries a widower with adorable twin girls (guest voices by Full House‘s Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen) who vie for attention with Eric when Mrs. Cartman gets pregnant using fertility drugs. Kenny hurts his knee curling. The McCaughey septuplets costar.

October 1o. The Southern Baptist Convention issues a press release commending the show’s “realistic depiction of today’s youth.”

October 16. Episode 2 airs: With the aid of a miracle, Stan and his sister discover the true meaning of Arbor Day. Jonathan Lipnicki guest stars as Stan’s guardian angel, who helps him get in touch with the spirit of Princess Diana.

October 17. The New York Post‘s Page Six reports a rumor that Matt Stone has been studying the cabala with Madonna and Sandra Bernhard.

October 23. Episode 3: Mr. Garrison gets transferred to rough-and-tumble, inner-city South Central Park, where he inspires his indifferent and sometimes intimidating students to throw their hands in the air only after he’s asked them a question. Kenny shuts his finger in a locker. Coolio guest stars as the ghetto school’s no-nonsense principal.

October 25. ABC execs bring in writers from the farcical romp Dharma & Greg to “lend guidance” on Parker and Stone’s scripts.

October 30. Episode 4: Kyle and Stan move to L.A. and rent a beachfront condo, where their next-door neighbors are two buxom dental hygienists (Elle McPherson and Rebecca Romijn) with hearts of gold and a taste for Scientology.

November. The radical reworking of South Park touches off a backlash from its core audience—fan-generated Web sites unleash flaming attacks on the show’s new direction. Guilt-ridden creator Trey Parker, in an attempt to get back in touch with his original fans, starts haunting chat rooms and becomes romantically involved with an online groupie, who turns out to be a precocious 12-year-old named Missy from Tifton, Georgia.

December. Despite the promise of a live-action feature film project, Stone and Parker pull the plug on their beloved scamps with a final, tear-jerking episode.

December 23. The final episode, “Au Revoir, Les Enfants.” Chef announces that he’s leaving the cafeteria to replace Sinbad as the host of Vibe. Mr. Garrison wins the National Teacher of the Year award and goes on a space shuttle mission. Kyle gets accepted to a gifted and talented program at a middle school in Aspen. Stan and Wendy pledge eternal love. Kenny unties his hood to reveal that he is actually E.T., the extraterrestrial. Cartman learns to accept himself for who he really is.

The First Season: South Park For Dummies

Danny Drennan explicates the meaning and meaninglessness of the first ten (relentlessly repeated) episodes

Original Episode: “The Spirit of Christmas”

In this five-minute short, we meet our main characters, the four scamps from South Park: Stan, in a blue ski cap with red pom-pom, red jacket, and blue pants; Kyle, green hunter’s cap, red jacket, green pants; Eric Cartman, light blue ski cap with yellow pom-pom, red jacket, brown pants; and Kenny, red parka, red pants. The children gleefully sing Christmas carols until Kyle is reminded he’s Jewish, so he starts singing “The Dreidel Song,” which brings on the Cartman critique, “Hanukkah sucks,” which escalates into a rousing chorus of epithets only stopped by the appearance of Jesus, who has come seeking retribution against Santa Claus, whom he claims has defiled the meaning of Christmas. Best Epithet Award goes to Cartman’s use of “pig-fucker,” last uttered by Mink Stole in Serial Mom. Jesus and Santa exchange blows, accidentally killing Kenny. The kids’ moral predicament (Jesus or Santa?) is solved by figure skater Brian Boitano, and Jesus offers to buy Santa an orange smoothie, as hordes of mice devour Kenny’s body.

Helpful references: Mortal Kombat, Edward Gorey’s Gashlycrumb Tinies, men’s figure skating

Kenny’s Cause of Death: pierced by a Santa projectile

Moral: Whether you’re Christian, Jewish, Hindu, or atheist, Christmas is about one very important thing…presents.

Secondary Moral: The eight days of Hanukkah provide capital incentive to become Jewish.

Episode 1: “Cartman Gets An Anal Probe”

Cartman’s alien abduction symptoms are recognized by Chef, whose postulation of a big metal “hooba-jube” implanted up Cartman’s butt matches Cartman’s “nightmare” exactly. The appearance at school of flaming flatulence and a giant-eyeballed anal probe that expands into an 80-foot-wide beacon also belie Cartman’s denial. Meanwhile, the “Visitors” kidnap Ike (Kyle’s puntable baby brother), the mutilation-phobic cattle want to hop the next train to Denver, Stan can’t talk to Wendy Testaburger without throwing up, and Cartman is re-abducted, only to catch pink eye from Scott Baio.

Helpful references: Communion, the Little Rascals, the golden age of Looney Tunes

Kenny’s C.O.D.: UFO-beamed onto the road, Kenny is stampeded by cows, then run over by a police cruiser.

Moral: Having a little brother is a pretty special thing.

Too Much Information moment: “‘You weren’t looking out for your little brother, Kyle! You know he can’t think on his own, Kyle! Brush and floss, Kyle! Where has that finger been, Kyle!’” —Kyle

Special Guest Star references: Scott Baio, David Caruso

Episode 2: “Weight Gain 4000”

Cartman’s plagiarized “Walden” beats out Wendy’s dolphin opus in the “Save Our Fragile Planet” essay contest. Meanwhile, Kathie Lee Gifford’s award presentation poses a perfect mayoral media opportunity, Cartman bulks up for TV, schoolteacher Mr. Garrison recalls the former Kathie Lee Epstein’s grade-school talent-show victory, and his hand-puppet sidekick Mr. Hat ends up in the psychiatric ward after seeking revenge on Kathie Lee. Such-a-fat-ass-he’s-unable-to-leave-the-house Cartman sees his TV wish come true on Geraldo, and Chef gives Kathie Lee “sweet lovin’.”

Helpful references: Princess Cruises, Magic, Taxi Driver, Lee Harvey Oswald, The Return of the Jedi

Kenny’s C.O.D.: impaled on a flagpole

Moral: “You can’t win all the time. And if you don’t win, you certainly can’t hold it against the person who did, because that’s the only way you ever really lose.” —Wendy

Special Guest Star reference: Mary Tyler Moore

Episode 3: “Volcano”

Stan’s Uncle Jimbo and his Vietnam vet sidekick Ned take a trip up the side of a volcano where they show the boys how to hunt various endangered and otherwise gentle, furry creatures with an arsenal of army-surplus weaponry. But Stan can’t bring himself to shoot, the volcano awakens, the Mayor employs media histrionics, Cartman’s scary-monster campfire story comes to life, an armless Ned does a “cancer kazoo” serenade of “Kumbaya,” and the townspeople trap the hunters on the other side of a ditch they dig to divert the lava to Denver. “Scuzzlebutt,” the mountain monster, performs a gasp-inducing wicker-basket rescue, but takes a bullet from Stan, who hopes to win his uncle’s approval by killing something.

Helpful references: The Atomic Café, Miss Saigon

Kenny’s C.o.D.: Crushed under a huge ball of molten lava, Kenny later receives a bullet to the chest.

Moral: “Some things you kill, and some things you don’t.” —Uncle Jimbo

Secondary Moral: “Only now in this late hour do I see the folly of guns.” —Ned

T.M.I. moment: “My geologist? Now? Tell him the infection is fine, and I don’t need another checkup.” —Mayor

Special Guest Star reference: Patrick Duffy

Episode 4: “Big Gay Al’s Big Gay Boat Ride”

Uncle Jimbo causes a homecoming-game betting frenzy over Stan’s quarterbacking ability, while Stan’s “gay homosexual,” pink-kerchief-wearing dog Sparky starts shtupping other pooches up the butt. Mr. Garrison explains the “thick, vomitous oil” that oozes through gay people’s veins, Coach Chef gives a pigskin sensuality pep-talk, and Uncle Jimbo and Ned booby-trap Middle Park’s mascot so that it’s time-bombed to go off during John Stamos’s older brother’s halftime performance. Meanwhile, Stan stumbles onto “Big Gay Al’s Gay Animal Sanctuary” while searching for Sparky and gets a historic tour of gaydom on Big Gay Al’s Big Gay Boat Ride. Stan learns to love Sparky for who he is, throws a spread-beating touchdown pass, and reunites the disbelieving townsfolk with their lost gay animals. Stamos’s brother finally hits the high F in Minnie Riperton’s “Lovin’ You,” blowing the Middle Park mascot sky high.

Helpful references: Pong, Solomon’s Key, The Wizard of Oz, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

Kenny’s C.O.D.: decapitated by the opposing team

Moral: “It’s okay to be gay!” —Stan

T.M.I. moment: “I haven’t seen so many children molested since….” —PA announcer

Special Guest Star references: George Clooney, Barbra Streisand, Rodney King, Hugh Grant

[embedded content][embedded content]

Episode 5: “An Elephant Makes Love To A Pig”

The size of Kyle’s mail-ordered elephant is problematic until a classroom discussion about genetic engineering results in the crossbreeding of the elephant with Cartman’s potbellied pig Fluffy; a science-fair-project war sparks up with Terrance, who is involved in human cloning. Meanwhile, Stan’s sister Shelly inflicts some dental-headgear-induced wrath on her brother, and the boys tour the South Park Genetic Engineering Ranch, where Stan’s stolen blood yields a mean-dispositioned, out-of-control Stan clone. The clone is dispatched by Shelly, who then stands up for Stan, while Cartman’s pig finally gives birth to something resembling Mr. Garrison, who awards the boys’ project first prize.

Helpful references: The Island of Dr. Moreau, Babe, The Omen

Kenny’s C.O.D.: launched into a microwave

Moral: “Perhaps we shouldn’t be toying with God’s creations. Perhaps we should just leave nature alone, to its simple one-assed schematics.” —South Park geneticist

T.M.I. moment: “If some girl tried to kick my ass, I’d be like, ‘Hey, why don’t you stop dressing me up like a mailman, and making me dance for you while you go and smoke crack in your bedroom and have sex with some guy I don’t even know on my dad’s bed!’”—Cartman

Special Guest Star references: Loverboy, Elton John

Episode 6: “Death”

Stan’s grandfather’s 102nd birthday wish is for assisted suicide, a moral dilemma for Stan that Mr. Garrison, Chef, and Jesus won’t touch with poles of various sizes. Kyle’s mother protests the fart-ripe Terrance & Phillip show, and encourages the townsfolk to slingshot themselves against the Cartoon Central office building. Doo-doo jokes abound concerning the Kenny-transmitted stomach flu (i.e., explosive diarrhea) and “Death” chases the supervision-less boys into town, where they all stop to watch Terrance & Phillip in a store window until the show’s sudden cancellation. Their favorite show off the air, the boys resort to gas fumes, crack, and porno, while Stan’s African safari-bound grandfather dreams of the statistical probability of voracious lion attacks.

Helpful references: Enya, A Christmas Carol

Kenny’s C.O.D.: touched by Death himself

Moral: “If parents would spend less time worrying about what their kids watch on TV and more time worrying about what’s going on in their kids’ lives, this world would be a much better place.” —Stan

Secondary Moral: “Parents only get so offended by television because they rely on it as a babysitter and the sole educator of their kids.” —Kyle

T.M.I. moment: “I’ve got the green-apple splatters!” —Mr. Garrison

Special Guest Star reference: Suzanne Somers

Episode 7: “Pink Eye”

After a pre-Halloween Mir space-station crash kills Kenny, his embalming takes a turn for the worse at the morgue, and in the morning a now-zombified Kenny meets the boys (in their Chewbacca, Raggedy Andy, and Adolf Hitler Halloween costumes); the boys make fun of Kenny because he’s poor and gay-bait Stan. The town doctor diagnoses fatal zombie-like symptoms as pink eye, Chef and the boys hunt for zombie genesis clues, Stan and Cadman go chain saw-happy, and Kyle negotiates a maze of Worcestershire sauce-hot-line dialing options. The day saved, the boys leave Kenny’s gravesite and return to their candy and Crack Whore magazine (featuring Cartman’s mom), while a stitched-up Kenny bucks for a sequel.

Helpful references: Phantasm, Night of the Living Dead, “Thriller“video, Carrie, Triumph of the Will, Star Wars, Pippi Longstocking

Kenny’s C.O.D.: Crushed by the Mir space station, Kenny is re-killed when Stan cuts him in half with a chain saw, and re-re-killed by a toppling cemetery statue, plus a crashing MiG jet.

Moral: “Halloween isn’t about costumes or candy, it’s about being good to one another and giving and loving.” —Stan

Secondary Moral: “Dressing up like Hitler in school isn’t cool.” —Puffy the Bear

T.M.I. moment: “That’s good, just use those mouth muscles like the girls in Beijing.” —Mr. Garrison

Special Guest Star references: Jackie Collins, Evel Knievel, Richard Nixon, Tina Yothers, Edward James Olmos

Episode 8: “Starvin’ Marvin”

The boys order a Teiko digital sports watch on Stan’s mom’s credit card in a TV giveaway. Meanwhile, Mr. Garrison conducts a Thanksgiving food drive, the head of the South Park Genetic Engineering Ranch messes with turkey production, and the boys show-and-tell a starving African child (mistakenly delivered instead of the sports watch) as the pissed-off, exponentially growing, experimental gobblers attack the town. Cartman is mistakenly exiled to a foodless, fly-ridden existence in Africa by black-suited agents in sunglasses, only to uncover a gluttonous Sally Struthers chowing down. The mayor dreams up a grab-a-can food gimmick starring Kenny, and Chef battles the mutant turkeys. “Starvin’ Marvin” returns triumphant and turkey-laden to Africa, switching places with a none-the-better-off Cartman, while Kenny’s poor family grapples with their no-can-opener existential dilemma.

Helpful reference: Braveheart, the letterbox version; Book of Job

Kenny’s C.O.D.: pecked to death by mutant turkeys

Moral: “It’s really easy not to think of images on TV as real people, but they are. That’s why it’s easy to ignore those commercials, but people on TV are just as real as you and I” —Stan

Special Guest Star references: Sally Struthers, Engelbert Humperdinck, Charles Dickens, Vanessa Redgrave, McGyver

Episode 9: “Mr. Hankey, The Christmas Poo”

Offended by the blatant religious overtones in the Christmas play and incensed that Kyle has been cast as Joseph—delivering a purple Jesus fetus from a moaning Wendy Testaburger—Kyle’s bitch-for-a-mom rallies the townspeople against the play…and Christmas. In a feeble attempt to please his mother, placate the townspeople, and thus put a stop to songs such as “Kyle’s Mom’s a Big Fat Bitch in D Minor,” Kyle suggests that the perfect non-offensive and non-denominational Christmas icon is Mr. Hankey, the Christmas Poo, who doesn’t discriminate by faith, just by fiber. Diagnosed as a clinically depressed fecalphiliac and nuttier than Chinese chicken salad, Kyle is committed as townspeople tear down insufficiently PC decorations. Mr. Garrison stages the most secular and avant-garde Christmas play ever, prompting a riot. Occult-loving Chef reveals that Mr. Hankey is indeed real. Inspired by faith, Mr. Hankey springs to life, sings a song, and saves Christmas as he leads South Park in a candlelit vigil outside Kyle’s cell.

Helpful references: A Charlie Brown Christmas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Jiminy Cricket, Al Jolson

Kenny’s C.O.D.: None. In an unprecedented turn, Kenny miraculously survives both electrocution and shark attack.

Moral: “Jewish people are okay.”—Stan

Special Guest Star reference: Philip Glass

The Characters: Child Support

In retrospect, perhaps psychological treatment should have been considered sooner. Certainly, the warning signs have been there for a while: poor motivation at school, bouts of hysteria, grisly killings, gay pets. With that in mind, we asked Dr. Ava Siegler, a renowned child psychologist, and author of The Essential Guide to the New Adolescence: How to Raise an Emotionally Healthy Teenager, to delve into the mysterious inner worlds of South Park‘s rambunctious jewels. “Since the show as a whole seems to be about anger, rage, and narcissism, it’s safe to say these kids could use some therapy.” Indeed. Her analyses follow. Zev Borow

Stan:

He seems the most normal. He has feelings. He cares for his dog, even when he learns it is gay. He tries to modulate aggression. He has what we would call an observing ego, meaning he can criticize himself. He has affection, seemingly, for the little girl who makes him vomit. He does have an intense sibling rivalry with his sister, who is abusing. One of the things Stan might conceivably work on in treatment would be standing up for himself. The abuse from his sister could make him more and more timid, cautious. But I’d be worried about Stan the least.

Medication: perhaps for his sister

Kyle:

He seems basically normal and seems to come from a relatively normal family environment. He’s close with his little brother, though there seems to be a bit of a sibling rivalry there. But Kyle is a sensitive little boy. He doesn’t want to kill things; he agrees to dress up as Raggedy Ann; he seems to have healthy relationships with girls. He’s also the one with the overweening, over-intrusive, overprotective Jewish mother. And I guess you could say that this has produced a child who, to the other kids, looks a little wimpy. Perhaps this could have an effect on the way Kyle deals with his masculinity. His mother could definitely use some parent guidance. She erodes Kyle’s self-esteem and self-confidence. You could expect Kyle to be more of a follower because of this.

Medication: Valium, for his mother

Eric:

He’s the targeted, neurotic fat kid. Cognitively he’s a mess. For all we know, he could have some major learning disabilities. But this could all have to do with the fact that, clearly, Eric has a pathological relationship with his mother. His mother keeps him a baby. She tempts and seduces him with food—with that cheese stuff he likes. His tremendous amount of aggression toward other people is probably linked to this underlying infantilization. I would recommend play therapy. We would play war, and I would point out the way that he cheats and makes himself feel big and strong by making other people small and weak. This is a boy who, underneath, has enormously poor self-esteem. He could wind up like that character in Dr. Strangelove, a military monster. On the other hand, he could equally become depressed and just get fatter and fatter and isolate himself even more. Or, he could take hold of his life, maybe when he’s a teenager. But it’s hard to imagine a positive outcome.

Medication: I’m not a big proponent of drugs for young children, but certainly, Eric might be helped by some Prozac. He could also have an Attention Deficit Disorder, in which case Ritalin could be useful.

Kenny:

He’s a kid who appears to be selectively mute. Usually this has to do with underlying aggression. Very interesting that Kenny becomes the kid with aggression problems when he’s aggressed against in every episode. This could have its roots in something in Kenny’s background—marital strife in the house, a depressed mother, an enraged mother. Or he might be what we call pathologically shy. If he isn’t helped, he’ll be compromised in both future academic and social settings. And though he is accepted by his little group now, as he moves on, people will likely get tired of his not speaking and might isolate him. That can develop into serious depression.

Medication: There are a number of serotonin re-uptake drugs that might work for Kenny, to say nothing of him just generally being more careful.

Leave a comment