San Francisco, 1994

A group of dykes, feminists, queer punks, and onlookers crowded an unassuming martini bar as Lynn Breedlove and a few friends used a chainsaw, blood, and parts of a pig’s body from a Mission District butcher shop to protest sexual assault, police, and art-bro bullshit.

“It was gnarly,” Breedlove remembers, noting that there was no warning for the audience. The performance was in direct response to the release of a zine called Answer Me, whose final controversial issue, The Rape Issue,gained popularity with shock-obsessed readers while deeply angering feminists.

“We didn’t know what the fuck, but we knew we were pissed.”

Little did Breedlove know that this night of performance would birth a queer punk poetry movement that would tour the country, and provide a platform for writers and artists to eke out critical and creative work for years to come.

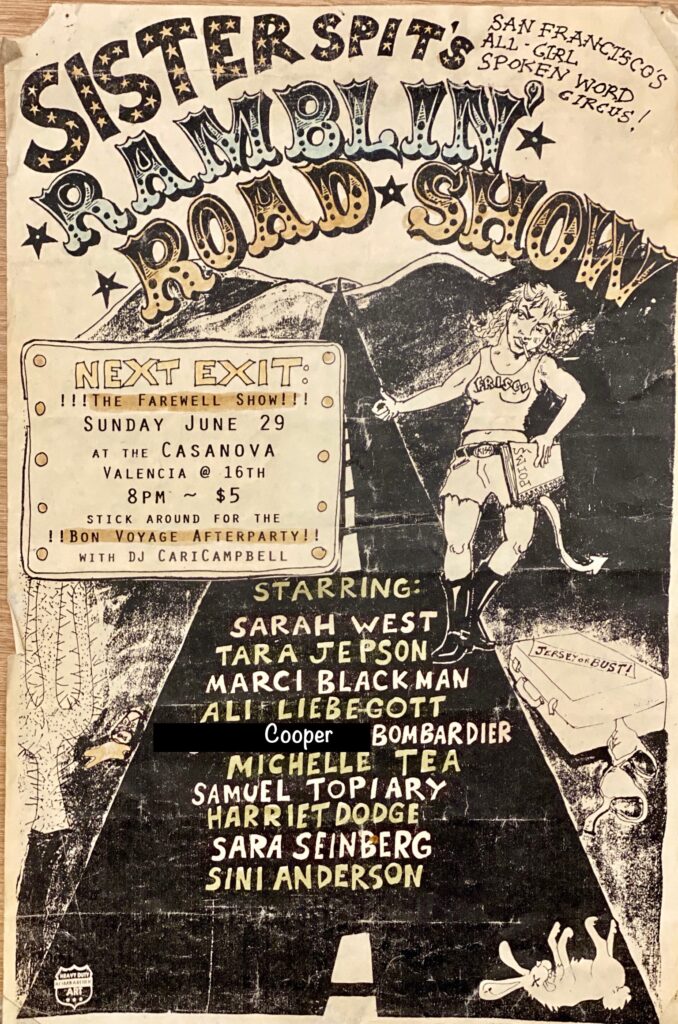

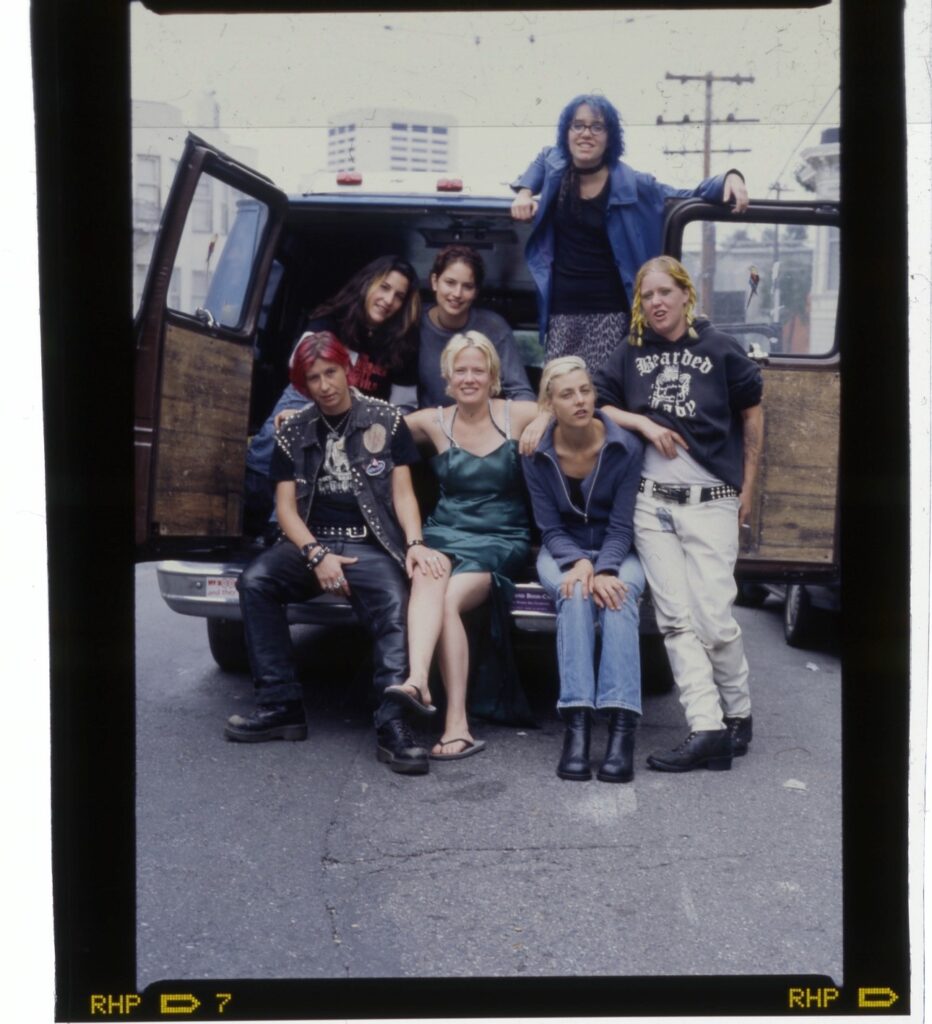

For the first time since 2020, provocative poetry roadshow Sister Spit will be physically hitting the road this weekend with a crew of new and familiar faces. Founders Michelle Tea and Sini Anderson, along with Sister Spit alum Beth Lisick, Lynn Breedlove, and Brontez Purnell, as well as newcomer Kamala Puligandla will be performing in Berkley, Los Angeles, and San Diego celebrating 25 years of touring and–as Puligandla calls it–the “Fuck You Spirit” that has propelled and sustained the Sister Spit community since their early chainsaw days.

Sister Spit Is Born

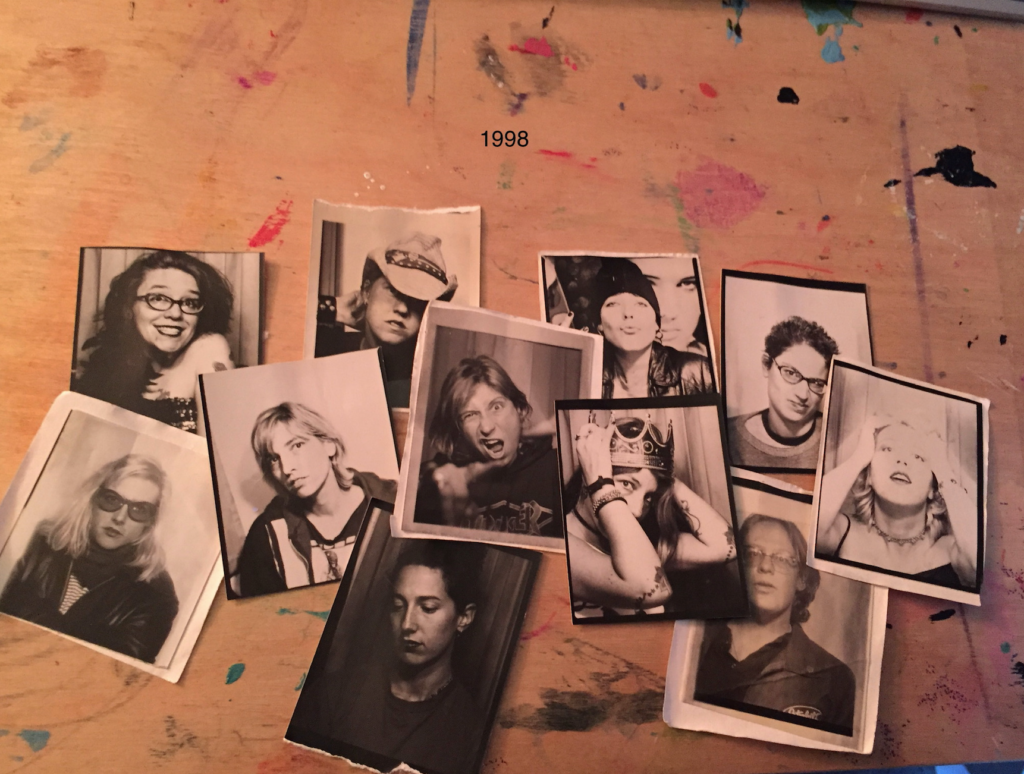

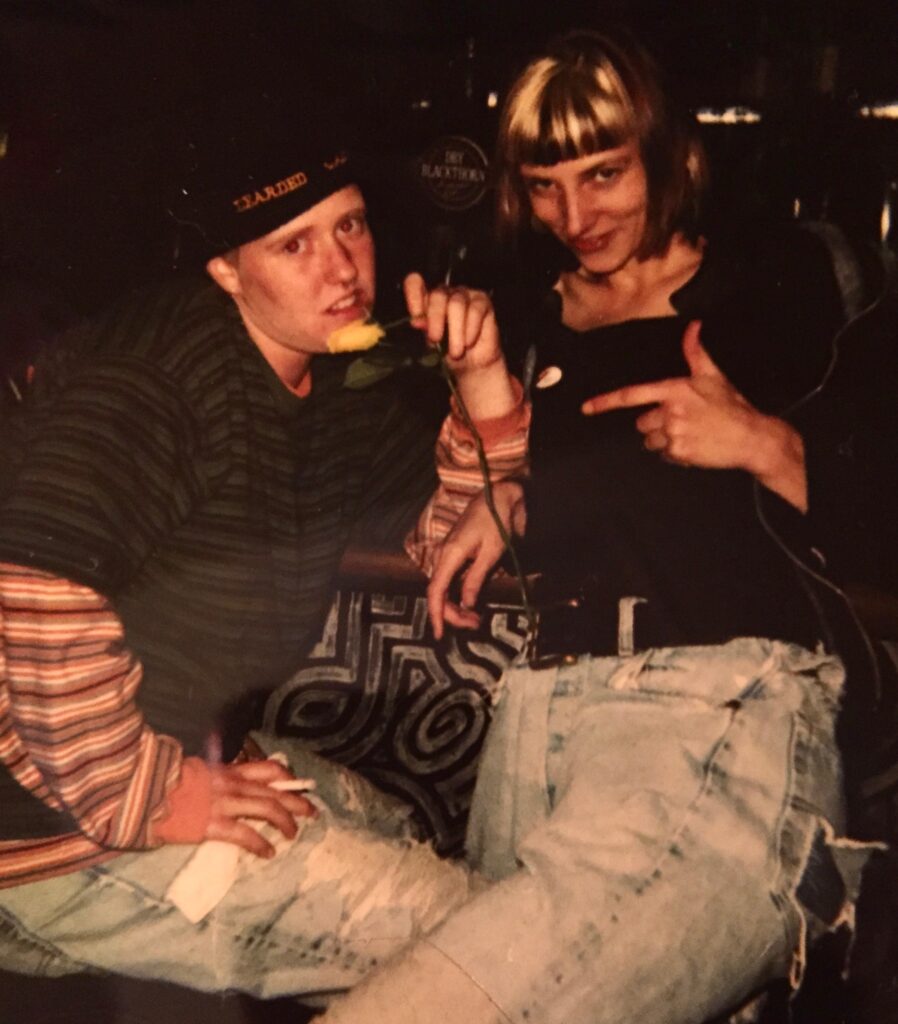

Sister Spit started in 1994 after a local booker from San Francisco’s Bearded Lady reached out to Tea and asked her to help Bay Area newcomer Anderson put together an open mic night. Tea, an avid writer, tarot reader, and performer in San Francisco’s queer scene, brought a stack of chapbooks–small and often cheap leaflets somewhere between a zine and a book–suggested booking everyone in the pile. Anderson was impressed and excited, and the two quickly started working together to produce the event.

The first event took place at Blondie’s, a bar in San Francisco’s Mission District that catered to a working-class crowd including a crew of older dykes in the 1990s before the dot com boom turned it into a cigar and martini hangout. The bill included Tea and Anderson as co-hosts, Breedlove doing his now legendary pig head piece, and several feminist performances including Daughters of Houdini, a duo who stood on stage making music out of menstruation.

As feminist art often does, the inaugural open mic stirred discussion and strong feelings among the community. A member of the audience was upset at animal parts being used as metaphorical art pieces and stole the pig’s head and ran down Valencia Street. Additionally, at the end of the event Tea proposed a boycott and protest of bookstores selling Answer Me, which prompted a writer in the crowd to push back, arguing that promoting censorship is dangerous even for queer feminists protesting harmful zines, opening up a dialogue about free speech with everyone in the crowd.

Tea remembers that poetry events in the ‘90s Bay Area DIY scene often centered on cisgenderheterosexual white men attempting to be Charles Bukowski, not experimental feminist work or queer writers. At the time Sister Spit was calling itself a girls-only open mic, and as language has evolved so too has the definition of Sister Spit, but this nascent space for people who couldn’t get booked was an important and necessary intervention.

An integral part of Sister Spit’s lifeblood is humor and weirdness along with queer critique, radical politics, and rage. Puligandla grew up in the Bay Area in the ‘90s so Sister Spit was on her radar even though she was too young to attend until college. “I always liked that it was really performative, and not just about quiet readings in bookstores.”

“We had a sense that there were some people who would want to participate,” Tea says, “but we had no idea how many and what they actually were looking to do.”

Get In The Van (But Not In a Black Flag Kind of Way)

Get In The Van (But Not In a Black Flag Kind of Way)

Sister Spit was a success and a breath of fresh air for the local scene, which inspired them to take it on the road. In 1997 they booked a tour with the help of Maximum Rocknrollclassifieds, a women’s travel agency, and a few slam poetry contacts. They filled two vans full of poets and hit the highway, playing bars, art spaces, and DIY gigs all over the US.

“We would have no place to stay,” Tea says, remembering the conditions of those early tours. In true punk style they would get on the mic and ask for someone in the crowd to host them, staying with strangers and new friends each night. “We only got hotels twice because there were problems – once because the van broke down, and once because a show fell through.”

“It was all word of mouth,” Lisick says, remembering the unpredictable pre-internet support they got from a network of queer people, feminists, touring bands, and even in the unlikely form of a Waffle House employee who begged to join. Lisick joined Sister Spit on multiple tours, quitting whatever bookstore or food service job she had to hit the road, even though most performers only took home about $80 at the end of the tour. “The art scene, the music scene bled over, there was nothing else like it and it was super exciting.”

The crossover and interplay between queer punk and Sister Spit is a big part of its legacy. As mentioned earlier, Breedlove is a performance artist and poet as well as the lead singer of the punk band Tribe 8. In addition to being a writer and ‘zinester, Purnell is a musician, dancer, and member of bands like Gravy Train!!!! and The Younger Lovers who was invited to join Sister Spit in 2010 after they heard him reading excerpts from his bookJohnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger? (that he eventually finished at a Sister Spit affiliated writing residency in Mexico). As a poetry collective, Sister Spit has recorded three albums, released by Mercury and Mr. Lady Records.

Moving Beyond the Whiteness of ‘90s Punk Feminism

While the 1990s were a period of revolutionary performances for Sister Spit, those early line-ups were very white, and in hindsight this fact is one of the only regrets that Anderson and Tea have about Sister Spit.

Back in the ‘90s in efforts to be fair, Sister Spit would take the names of people who wanted to be a part of the event and put them into a hat to choose at random. But even within that hat there were few people of color included. Breedlove used to go to BIPOC [bisexual people of color] open mic nights and ask poets to come to Sister Spit, but most people were not interested. “What Black person in the ‘90s was gonna hop in the van with a bunch of crazy white people?” Purnell jokes.

“I also don’t jump into a van with a bunch of white people, and I did mention that to Sini and Michelle early on,” Puligandla says, but that Sister Spit “Fuck You” spirit [is something] that I really hold dearly, I’ve read lots of Tea’s work before I met her, and it’s something that I trust.”

After being in queer spaces for years, Puligandla believes that creating spaces where people of color and white people create together is something you must intentionally create, not something that will just happen without effort. “Before I joined Autostraddle I had the exact same conversation with them. A lot of long-standing feminist art things happen to have started with white people — there are many reasons for that. I don’t think that’s great. But, do I think that it discounts everything that happened? No.” Puligandla reminds us that there were BIPOC art projects happening at the same time that didn’t get the press or access to venues that white art projects did.

“Black folks, brown folks need to be motherfuckin’ centered in this country,” Breedlove says. He acknowledges that white punk and feminist scenes have often been “bullshit” for people of color to navigate, something he wants to be a part of changing by listening and learning and acting when appropriate. “Feminism isn’t about some white lady marching around with a sign in a dress saying “I’m just like you” like [Mattachine Society] had to do in the ‘60s! The Sister Spit spirit to me is about rage [and] creating a safe space of love, where we get to talk about that rage with each other.”

Current Tour

Seeing new writers and creative people that have that “Sister Spit” spirit, as well as all the cool new work that old friends were doing, made Tea want to get back in the van.

This weekend’s mini tour will have something for everyone. Tea will be reading from her new memoir Knocking Myself Up (released on August 2)which focuses on her journey becoming a parent as a queer 40-year-old uninsured woman. Purnell will be reading new poetry as well as new work from his upcoming sci-fi book. Breedlove will be performing a new personal piece that he’s workshopping to take out with his new band Commando. Lisick will be reading new material based on her recent work with people who have dementia. Anderson will be sharing her Catherine Opie documentary as well as stories about Sister Spit while showing archival footage and photographs that she is hoping to turn into a documentary. Puligandla will be reading from her book Zigzags, as well as a new unnamed project set on a ranch in the future.

“The same forces that we felt like were breathing down our necks and making our life hard in the ‘90s are still here,” Tea says.

Anderson and Tea still believe in the punk power and potential of Sister Spit just as much as they did at Blondie’s in 1994.

“Back in the day nobody had a therapist,” Anderson says, “There were a lot of people performing who wouldn’t follow that path, but whatever fucked up experiences they had in their childhood or in the world at large, that energy needed a place to go. [Deeply personal trauma] became not so tragic, but triumphant.

“I needed an outlet. I’m going to be really cheesy: Sister Spit saved my life”

Leave a comment