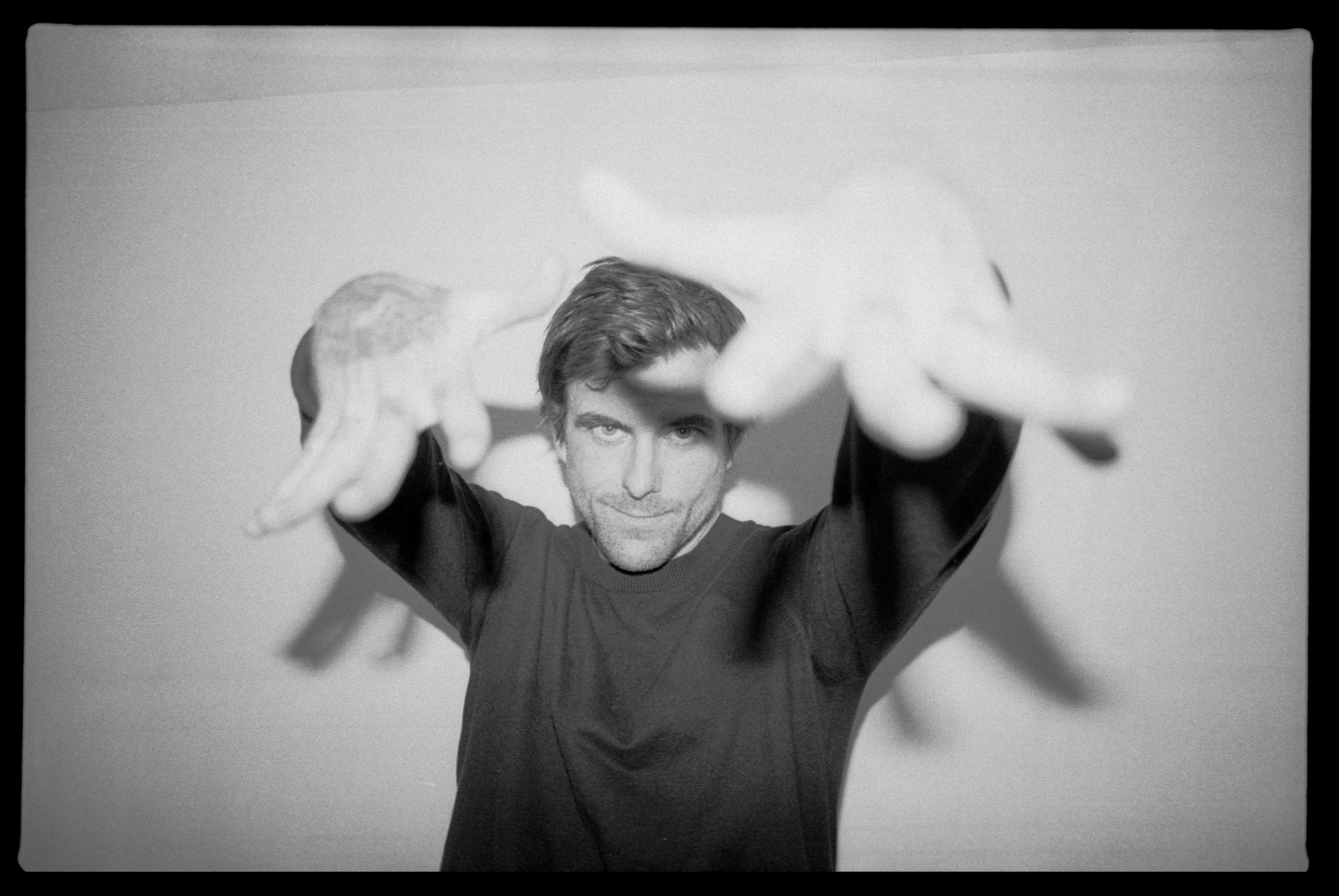

When you talk about successful artists who have well-documented struggles with addiction and mental health, you pretty much have to mention Anthony Green. As the lead singer of the long-running rock band Circa Survive (amongst a long line of others, like Saosin, Fuckin Whatever, and the Sound of Animals Fightings) and an accomplished solo artist, Green has almost always been an open book about the challenges he’s faced.

Fresh off a tour with Tim Kasher (Cursive) and Laura Jane Grace (Against Me!) and the release of his latest album, Boom. Done — which is every bit a dissection and brazenly open exploration of the triumphs and troubles in the world he orbits — Green took some time to sit on a lawn on a beautiful sunny day and chat about some of the harder conversations many people tend to shy away from.

[embedded content][embedded content]

SPIN: Let’s start at the beginning. When did your mental health issues start to arise?

Anthony Green: My thing starts wherever everybody’s things starts. When we’re little kids, we’re these extra sensitive creatures, and if we don’t get the proper emotional nourishment, we can develop weird coping skills. When I say weird, I mean in the sense that you develop a coping skill that ties you to something that you might also consciously know isn’t good for you in the sense of being able to accomplish all the things you’re here to accomplish, but it’s a coping mechanism nonetheless. Mine is just like everybody else’s. I learned to eat when my feelings got overwhelming. I learned to self-medicate. I learned to self-harm. I think that’s a journey that a lot of people can relate to, and I think that’s why music, art and poetry convey such a strong emotion from people who deal with addiction and mental health stuff. It’s because it’s something that we’re all dealing with, and we’re also all simultaneously trying to hide or diminish or compare our story to someone else’s, so that we could alienate ourselves in a way or not give ourselves what we need.

I think about the hiding thing a lot, especially in music. I was big into punk rock, and it just felt like a thing we didn’t talk about even though it was prevalent. When you were coming up in music scenes, did you notice that?

I did. Let’s say I would get really drunk when I was a kid, and I would have a night where I would run off when we were on tour and the band wouldn’t know where I was — and the next day when it was time to leave, I didn’t know where I was. Things were kind of a mess. For a really long time, that would happen and nobody would really know how to talk about it. I wouldn’t know how to deal with it, the band wouldn’t know how to deal with it, and it creates this tension where everybody just hopes that it’s going to go away or get figured out on its own. Problems like that don’t just go away, they just get bigger and bigger, or they hide or transform. As I got older, I think it got more apparent that I wasn’t going through a phase — that I had been dealing with addiction stuff and also simultaneously dealing with mental health issues. This was stuff that I didn’t have a vocabulary for — there was no language. Any language there was around it for me was so sidechain to shame, and I felt defective.

It wasn’t until later that I realized that there was stuff to be proud of. That these reasons why I have my issues with substances are why I’m dealing with manic behavior and are things to be proud of. When I look at it from that perspective — where it’s given me so much, like the ability to sit in a feeling and really analyze the feeling, and maybe give me a better chance at trying to convey it through music or poetry or something — that’s given me everything. To look at it as something shameful or that’s there to hurt me, that just creates a boundary where there doesn’t need to be one. It creates a problem out of the solution, and I’ve been doing that forever. So, I’ve been trying to shift the focus into using the energy and momentum that my addictive personality and my bipolar will propel me into a direction that I could use to my benefit.

There’s such a heavy stigma around so much of it, where it’s like “You are an addict” and we’ve coded that as a shameful thing. We’ve turned it into this bludgeon that we can use to hit somebody over the head with, as opposed to it just being a thing that we have.

It’s easy to vilify somebody who’s got addiction stuff. It’s easy to say “They will lie about their addiction” [or] “They will steal.” It’s not an easy task to look at somebody who’s dealing with this and be compassionate, because sometimes it’s hard to be compassionate with somebody who is dealing with this stuff. You might not have your head wrapped around the fact that it’s not some choice, and just with a little bit of that skepticism mixed in with having your peace of mind taken — or your actual stuff — it becomes difficult. I think we need to start examining how we approach the situation at the core of it. That’ll grow into a scenario where we have more understanding and compassion, and there’s less opportunities for us to miss when somebody is self-medicating or self-harming.

How was it when you started trying to talk to people in your life about these issues?

It was almost never something I volunteered for. I would find myself in a situation where I was isolating, and I would isolate until I got sick enough that it was affecting other people in a way where I would do it until I got caught. It was almost never a thing where I was like “I’m having a hard time, I need to go to the guys.” It was “I’m having a hard time, I need to figure out how I can hide this better.” I feel like a long time ago, as a little kid, I made this agreement with myself that everybody else was OK and I was lucky to be here with the world. I was the exception. I didn’t give myself any love, and I didn’t know how to accept love from other people. I think that a lot of people’s issues stem from that — this decision that we made a long time ago that we’re defective, or that we’re bad, and that we’re not deserving of love. That’s a really difficult thing to talk to people about. When you’re not used to accepting love, it’s hard to go to people who care about you and tell them that, and that’s what I’m mainly working on now. I’m in therapy. I go see support groups. I have a number of resources. I’m fortunate in that way where I have so many resources at my disposal. There are people who just don’t have the same resources, and I feel like we need to figure out ways so everybody can afford to get mental healthcare and can afford to have somebody to talk to.

[embedded content][embedded content]

We’re trained to not communicate these things. It was ingrained in me when I was young that those are problems you don’t tell anybody about. But eventually we have to learn to trust each other.

That’s the hard part. When I let my guard down, I’d make a connection with somebody. I remember thinking “Oh my God, this vulnerability is the place I need to be coming from.” But soon after that, I’d forget how important that was, or how good that felt, or how beneficial it was. I have to remember to take that leap of faith again and again and again. Whenever I was feeling blocked up or I was angry or resentful or something was going on, I remember that I have to talk about this. I have to be open about this. But I forget that all the time.

I read that you were initially going to put out your new record as a new band project, because you didn’t want to put it out under your own name. What was the reasoning behind that?

When the pandemic hit, I started writing with my buddies Tim and Keith from Good Old War, who had broken up and were making new music. I wanted to do a new solo record, but I was afraid that calling it an Anthony Green record was going to hurt it rather than help it. The story I was telling myself was that I wasn’t good at making music anymore and that nobody gave a shit about what I was doing. It’s the same sort of thing that everybody goes through when they have that self-doubt moment where they’re like “I’m not good enough. Nobody likes this shit. What’s the point?” I think that, for me, that was grounded in a lot of egocentric stuff, where I was really focused on outside stimuli and outside elements. I decided throughout that journey to say “Fuck it” and to just do my best at making a solo record that I would like, and not focusing on anything beyond that — not really worrying about whether or not I’m good enough, if people like it, or any of that shit — and just enjoying making it and experimenting while making it.

So I did that, and took my time with it. I did it with Keith Goodwin — who is my best buddy — and it’s the first time we’ve ever worked together. The record was etched in a period of time in my life where it was really strange, I had gotten clean. My brother-in-law died of an overdose. I wasn’t able to tour. I felt completely alone in the world. I was using the album as something to help me feel connected to anything. It was like when the cartoon guy falls off the cliff and he’s just holding on to the tiny little thing. That’s what the album became to me. It was this tiny little reason for continuing. I wanted it to feel like a million people playing in a room because I was lonely, and I felt like I didn’t want to be lonely. I wanted it to feel like I was in a big band. I wanted the songs to sound happy. I wanted to represent that rather than just everything feeling so hopeless. So then I felt like I wanted to put my name on it. I wanted it to be something that I loved, and that represented me and a part of my life, and I wasn’t relying on how many hits it was going to get or how many downloads or streams it was going to get. It was just going to exist in a way that was to be of service, and that was it. Whenever I’m coming from a place where I’m looking at it as being of service to whatever I can, then I’m grateful and satisfied with it. When I start looking at it in comparison to what other artists are doing or rooted in an egotistical place of desire, I’ll always feel like it’s not enough.

Leave a comment