In the early evenings of late January 1991, after local news and Wheel of Fortune, the majority of American families tuned in to CNN’s coverage of Operation Desert Storm, the first ever real-time, front line broadcasts in the history of combat. This was groundbreaking stuff, honest-to-goodness live war, featuring play-by-play from on-site reporters and color commentary from retired senior military in the studios. This was next-level nationalism, unprecedented patriotism, televised mass murder with the feel of a dark sporting event and the lo-fi broadcast resolution of a video game.

The night vision footage of green rockets and tracers racing back-and-forth across the black skies of Baghdad looked an awful lot like the last level of Asteroids. The Apache view screens with 8-bit graphic crosshairs pounding Lockheed Hellfire missiles into buildings and dots that scattered like ants were spot-on Nintendo. And the overhead video from actual B-52s (not the “Love Shack” kind) raining savage oblivion on bridges and convoys — dead-ringer Atari, with a touch of Frogger viewpoint.

The arcade-quality visuals lessened the soul-sucking reality that people were dying and America was loving it from the living room. By Desert Storm’s end, in what was gleefully referred to as “shock and awe,” the US and allies had run 115 assault missions per hour, around the clock, for six weeks straight, each delivering 90 tons of explosives.

FM radio drive-time personalities across the nation made merciless Desert Storm skits and parodies built of cultural ridicule. American political and spiritual leaders offered no objections, as protecting Muslim feelings was not a campaign promise. No, the only truly offensive culture, the real seismic threat to America’s skewed and mostly delusional sense of its own morality, was “gangsta rap.”

Three months before the Iraq war, an especially noxious new strain of gangsta rap from Houston, Texas had bubbled onto conservative radar. More than just a collection of offensive songs, the self-titled album of a crew called Geto Boys was essentially one 55-minute-long offensive act, a next-level form of unpleasantry that completely redefined music, and exposed white America’s deep fear of a simmering black social volcano cemented over for decades.

The subjects for the songs on the record were (and still are) just plain horrible: extreme murder, rape, and perhaps most heinously, necrophilia. When heavy metal bands spoke of the ineffably foul act — for instance, Slayer sang about banging corpses in ’89 — concerned parents predictably appeared on Geraldo, but when Geto Boy Bushwick Bill, a black dwarf, rapped about it, the response was abject horror, from community chapels to the White House.

To be clear though, Geto Boys shit was real. Lyrics about pistol-whipping women, robbing elderly blind men, dismembering prostitutes with machetes and chainsaws and executing crackhead priests (all in one song) — taken from true stories and police cases that never made it beyond Houston’s Fifth Ward, the cracked-out battlefront of a neighborhood group members Willie D and Scarface grew up in.

Well, that’s offensive! Why, yes it is, and with this lyrical form of “shock and awe” Geto Boys intended to deeply offend, as a last ditch attempt to draw the attention of a nation ignoring all homefront wars, towards an abandoned community left derelict and broken from societal disregard, that had become its own terrible universe.

In 1979, during the Geto Boys’ childhoods, Texas Monthly reported Fifth Ward to have “far more pawn shops, loose dogs, abandoned buildings, bars and broken windows” than “sidewalks, streetlights, fire hydrants, parks or garbage trucks.” One in four streets had no drainage system, and of those that did, half simply drained to open, rotting ditches.

These were resort conditions compared to what was on the way.

Hell embroiled poor, mostly black neighborhoods throughout the ‘80s as crack invaded. Shortly before the release of the Geto Boys LP, a convicted killer interviewed by the Houston Chronicle said the Fifth Ward had become “a war zone of nightly shootings, fistfights and police harassment” where “seven-year-old children know how to handle pistols” and “the right amount of money can buy any weapon, even hand grenades.”

Similar Hadean scenarios existed in Philadelphia, where, in 1985, Schooly D released his “PSK” (short for Park Side Killaz) single, universally recognized as the first gangsta rap record. Boasting the industry’s first sex, drugs and murder narrative, “PSK” was groundbreaking, but melba toast compared to what was on the way.

Two years later and 2,700 miles west, L.A.’s Ice-T recorded “6 ‘N The Mornin”, a west coast appropriation of the style and flow of “PSK”, for his debut LP Rhyme Pays, an album so profane it earned it the first black-and-white parental advisory sticker (a failed recording industry campaign, strongarmed by conservatives, against “explicit content” that actually ended up attracting young, impressionable listeners, and selling way more records!).

And across town in Compton, N.W.A.’s Eazy E pushed the edge of the envelope with “Boyz N Da Hood”, another “PSK” nod based on “6 ‘N The Mornin’”, before N.W.A. pushed that envelope right down society’s throat with 1988’s Straight Outta Compton album.

Ice-T’s side project, heavy metal band Body Count, released the rather unambiguous “Cop Killer”, earning White House fury from VP Quayle and Bush — and Charlton Heston, who stormed the record label’s parent company Time-Warner shareholders meeting, red-faced and shouting, waving printouts of Body Count lyrics.

(Such is God’s dry sense of humor, that Heston at the time was the NRA spokesman and was pushing to legalize a bullet nicknamed the “Cop Killer” by law enforcement, for its ability to penetrate bulletproof vests.

Geto Boys did some serious pissing off too, though their original mid-’80s incarnation (featuring no one you know), was far more virtuous. Ghetto Boys with an “h” and extra “t” were a short-lived, hugely-popular Run DMC knockoff and considered the first real southern rap group. The safe Boys shot to fame in 1986 slanging vinyl singles out of their trunks: most notably, “Car Freak”, about their broad knowledge of engine parts, and the obligatory, soft-posturing flex “You Ain’t Nothin / I Run This.”

In 1988, high on life and life alone, the group released “Be Down,” an incredible lapse of judgment encouraging the hip-hop unfathomable – report all criminals to local police. Pledge-allegiance-to-the-law was not an inner-city hit, and hilarity ensued. Two members quit and slunk off. A backup dancer named Little Billy grabbed a mic, and with pre-paid studio sessions approaching (for a group with now only one, new, member), perhaps the fiercest 180 in the history of music began.

Having had damn well enough good clean fun, the group’s Lou-Perelman-meets-Suge-Knight mold of manager, J Prince, seized the reigns, and swearing dark oath to the gangsta rap phenomenon, began to script a brutal, derogatory and invasive crew meant to out-offend the Ice-T’s and N.W.A.’s of the world. After dismissing the remaining two original Ghetto Boys, while retaining Little Billy and the group’s DJ Ready Red, Prince set to work courting complete instability.

Willie D, a 21-year-old Golden Gloves champ raised by two alcoholic and abusive parents in the Fifth Ward, and known to fight audience members at open mics, was signed on sight, told to act monstrous and rhyme reckless. Fresh off a bid for armed robbery, the act was no huge challenge.

Scarface, an 18-year-old high school dropout and former drug dealer was cast as a cold, introspective hustler, a natural fit in look and demeanor. However, having been recently discharged from a psych ward after a suicide attempt, this was probably not a perfect match for his then mindstate. In this instance however, insanity was a commodity, and Prince drew up a contract immediately.

The pair were live wires, but Little Billy, known to the government as Richard William Shaw, was to become the real horror show. As Bushwick Bill, the 3’8” Shaw was paid to play a ferocious sociopath on a kamikaze course through society, a role that called for a type of rage and recklessness that had invaded his youth, and nearly driven him to murder.

In 1973, Bushwick’s family immigrated to New York City from Trenchtown, Jamaica, in an attempt to escape the violence ravaging the island’s south (somehow, random machine gun fire outweighed the coolness of the fact that Bob Marley often played backyard soccer with Bill’s dad). Unfortunately, the Shaw’s move was a jump from the frying pan into the fire, as their new Brooklyn neighborhood was a wilderness of drugs, gangs and unchecked crime — not the best playground for a seven year old.

In the Showtime documentary, Bushwick Bill: Geto Boy, Bill recalls walking to his new school and seeing an infant thrown from a 7th floor window, by a man demanding money from his girlfriend, land impaled on a fence in front of him. Later that morning, and every morning for the next four years, Bill was harassed and beaten by bullies, until finally snapping in 5th grade and knuckling down anyone within reach.

Fists became useless in junior high, replaced by razor blades, shanks and youth gang assaults, and by high school, Bill’s Brooklyn had become kill or be killed. After suffering a particularly brutal assault, that his attacker’s father cheered on and laughed at, Bill stole a fireman’s hatchet (nearly the length of his body) from a hardware store and chose to pursue his assailant.

After crafting a backup homemade ninja star made of razors, Bill and his massive axe crawled beneath a car in front of his target’s home and waited -– until a passing friend noticed his leg, pulled on it, and convinced Bill to join him at the movies, where a ghetto-youth-meets-God pulp cinema classic just happened to be playing.

While watching the film, Bill experienced a true and deep holy revelation that led him in search of Christ and, eventually, to a Bible studies degree at a Christian academy in Duluth, Minnesota. Upon graduation in 1986, he committed to join a ministry in India, but before leaving, booked a very fortune-changing one week trip to visit his sister in the Fifth Ward.

Upon arrival, he set out to explore his sister’s neighborhood, and after wandering into a hip-hop dance club, came to realize Texas was not all white, mustachioed cowboys. Having grown up in New York during the birth of rap culture, Bill had become a locally-famous break dancer by his early teens, so with India on the horizon, he pushed through the crowd to drop some final moves for nostalgia.

Seeing a b-boy dwarf rock windmills and headspins sent the crowd into a frenzy, and at night’s end, the house DJ pulled him aside and suggested he meet with local rap manager and label boss, J Prince. You know where this is going. At lunch the next day, Prince offered Bill a job as a choreographer for his group Ghetto Boys, and just like that, his gig with God was over.

He accepted, cut communications with the ministry and never left Texas.

Three years later, J Prince’s potent new Willie, ‘Face and Bushwick Ghetto Boys lineup spawned 1989’s Grip it! On That Other Level, a seething thunderbolt of an album that established the group as an evil, southern N.W.A.. The track “Size Ain’t Shit” (which there’s no use explaining and must be experienced), introduced Bill as a mad and maniacal miniature, down for whatever and bound for the grave.

In between loads of cartoonish ultraviolence and B-movie horror ephemera came some honestly unutterable lyrics, which Bill fought his faith to perform. “I started becoming Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I had just graduated Bible school… and here I am rapping about killing and mass murdering and raping,” Bill told Showtime. “I started being a drunk, I started doing hardcore drugs just to be able to rap those lyrics.” Telling himself that he wasn’t promoting, rather exposing, the darkness of the ghetto, he pressed on.

In the TV One feature Unsung: Story of the Geto Boys, Bill clarified the intentions of the group’s Grip it! album, explaining “We were telling you these are the traps and the pitfalls…but we say it in the first-party, we make it sound good to make you hear how bad it is.” Nonetheless, backlash came pouring into Texas from across the country (to Prince’s delight, excellent PR), grabbing the attention of established industry figures, including one of the art form’s bearded pioneers.

One humid Houston day in the newborn 1990s, Def Jam cofounder and production deity Rick Rubin was wandering the streets of the Fifth Ward, asking around for the Ghetto Boys, before locating and signing them to his personal label, Def American.

Having worked with Public Enemy on 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Rubin was no stranger to monetizing controversial art, and his Ghetto Boys plan was a classic “quadruple-redo”: for a fresh start, rename the group “Geto Boys”, re-record the Grip it! album in better audio quality, remix with a dusting of the mysterious Rubin life force, then re-release, on a larger scale.

After adding an album cover resembling The Beatles’ Let it Be, the gang did just that, and with the resulting self-titled album’s debut single “Do it like a G.O.”, threw epic roundhouses at crooked politicians, corrupt cops, black-owned radio and the KKK. The song lit an absolute dumpster fire on the front lawn of mainstream America, though the worst of the worst lay within “Mind of a Lunatic,” an album track that, with lyrics both Mansons might object to, spread the fire to the corporate penthouse.

At the behest of senators, churches, special interest groups, and even the CD manufacturer, who refused to press copies, Def American’s parent company Geffen halted the release of Geto Boys, citing “violent, sexist, racist and indecent” content. Undeterred, Rubin secured new distribution, though by its release date the group had already been banned across the US — venues wouldn’t book them, record stores wouldn’t sell them, and those that did kept their copies behind the counter.

It got worse. Months after the album’s official release, a pair of Kansas teenagers claimed in court they were “temporarily hypnotized” by “Mind of a Lunatic”, leading them to shoot and kill a random passerby. The boys’ defense attorney warned the jury: “There is an imminent danger to young people getting hold of this thing. It can literally mesmerize you from the repeated bass sounds that come from it.” Post-trial (the teens were convicted), Sen. Bob Dole and Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) joined the public damnation of Geto Boys, leading Def American to drop the group without comment.

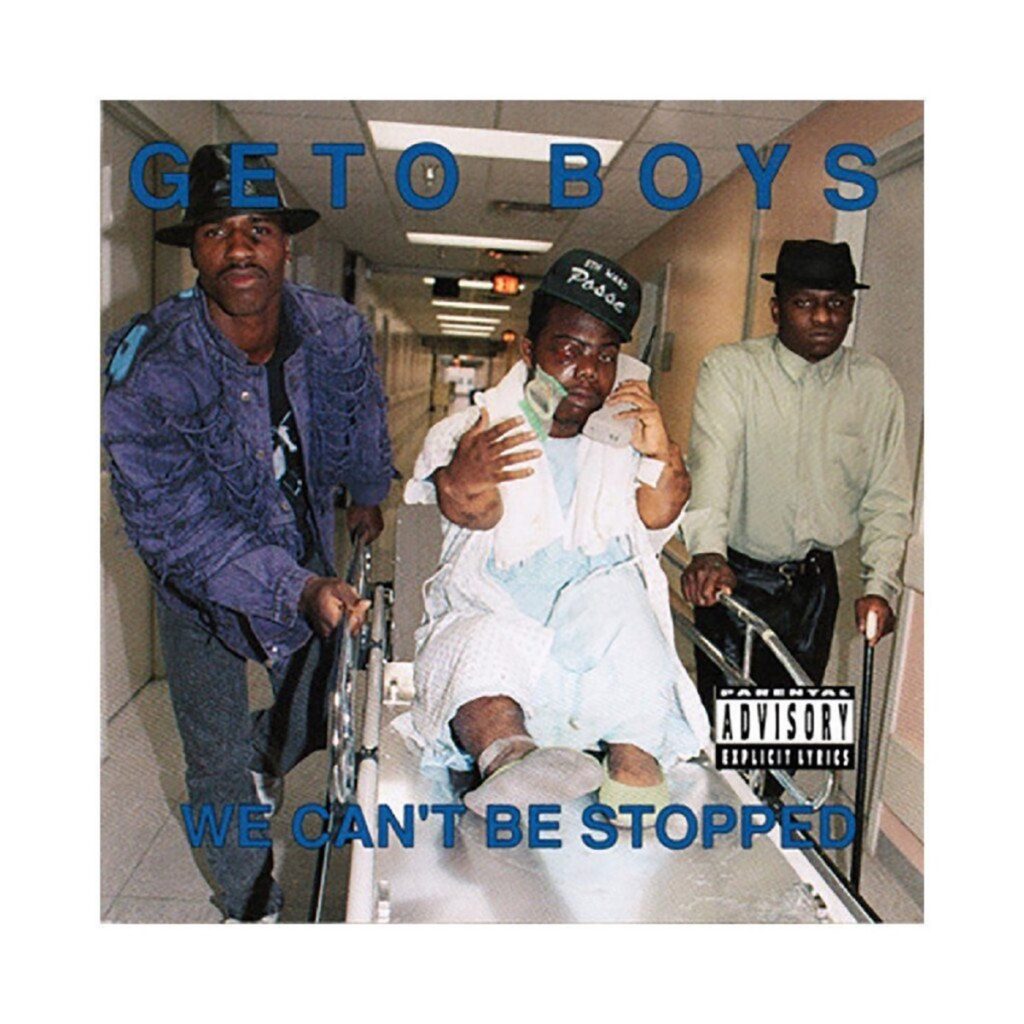

Bloodied though somehow not beaten, the Geto Boys returned to J Prince’s Rap-a-Lot label for their fourth LP, We Can’t Be Stopped (the one with the infamous one-eyed-Billy photo). You’ve heard the rumor, and if you haven’t, yes, that hole in his face on the album cover is real, the result of a self-inflicted gunshot wound that was actually part of a thought-out, if not completely deranged, life-insurance scheme.

Bill began to plot a means of death that would pay out his policy to his impoverished mother. Suicide nullifies life insurance, so, as one would, Bill tried to force his girlfriend to murder him. Storming into her apartment high on PCP and Evergrain 190-proof, he drew a gun and threatened to kill both her and her child — unless she killed him first. While forcing the gun into her hands, a shot went off and sailed through his right eye socket. Close but no cigar.

Taken to ER to scrape out cornea remainders, Bill refused hospitalization, and contacted his bandmates for an immediate pickup. The infamous picture of ‘Face and Willie rolling Bill out on a stretcher, taken by a tagalong J Prince, is the real-deal. Eventually used for album art, it sure was great promo, but maybe Bill should’ve accepted treatment; he later spoke of suffering migraines that could only be stopped by banging his head on walls.

While still plenty explicit, We Can’t Be Stopped served as another huge posture-shift for the group, eschewing rap’s typical boast-and-brag for the blues tradition of lamenting trauma caused by loose living. Its hit single “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” was an entirely new type of hip-hop, a desperate wits’ end confessional — no MC had ever questioned their own sanity in front of millions.

In rapping about praying for a way out of the drug game, while contemplating suicide in church, Scarface acknowledged feelings of weakness and spiritual need that a generation of black males had been conditioned to ignore, a move fans would later credit with helping them address their own depression and mental health issues.

Southern hip-hop historian Maurice Garland spoke to NPR about encountering the song as a child in the early ’90s — during a church service. “[The preacher] said, ’it’s like that Geto Boys song, when your mind’s playing tricks on you.’ He was breaking down the depression, the drugs, the anxiety, the everything, he was corralling all this into his sermon.”

As gangsta rap at large continued to worship hustling, the Geto Boys made a conscious decision to address the dead-or-in-jail futility of street life, with Willie D explaining, “Nobody did a song about showing the downside of being in the drug game, and so we wanted to cover that side…we didn’t mind being boycotted, we didn’t mind being protested.”

And they still certainly were, though by ‘93, rap of all forms and flavors had breached the mainstream, and the Geto Boys headhunt had slowed significantly.

The group’s next four LPs become a revolving door —1993’s Till Death Do Us Part (which hit gold thanks to top 40 hit single “Six Feet Deep”), saw Willie D temporarily replaced by southern rap titan Big Mike. Three years later, Willie D returned for The Resurrection, and in 1998, Bushwick bounced before the group’s Da Good, Da Bad & Da Ugly album, going solo under the alter ego Dr. Wolfgang Von Bushwickin’ the Barbarian Mother Funky Stay High Dollar Billstir (say that one five times fast!).

In 2000, Scarface became president of Def Jam South, where he helped grow the career of Ludacris, before the original Geto Boys lineup reunited in 2002 to record The Foundation, their final full album, which crawled to a January 2005 release. So-so solo work continued here and there until a 2009 reunion at Cypress Hill’s SmokeOut festival in San Bernardino, California, which led to six years of occasional group appearances.

In 2015, the group convened a Kickstarter campaign, soliciting money to record a “final” final album entitled Habeas Corpus, for which high-level donors could earn some amazing benefits — a golf outing with Scarface, a night of bar-hopping with Bushwick, or a social media endorsement from Willie D. Top-tier donations earned an overnight spot on the Geto Boys’ tour bus, and for the highest donor, a custom, full-size Geto Boys casket with an autographed pillow.

Despite having just finished a well-attended tour, the group’s Kickstarter fell on its face, ultimately failing to raise even half of its $100,000 goal. In a VladTV interview, Scarface admitted that because it looked like fans didn’t want one, another Geto Boys album would never happen. In an ending completely at odds with their volcanic career, the Geto Boys simply petered out, replaced by rappers making music even more salacious and outrageous than theirs.

Facing the fall of his platoon (and fearing boredom?) J Prince himself immediately shouldered the rifle and fired his own diss track at fellow label bosses Birdman, Suge Knight and Diddy, entitled “Courtesy Call” wherein Prince informs the shiny, happy Bad Boy that he has “opened the doors for his family to be touched.” Yikes! Diddy later went on to change his middle name to Love — a voluntary, free spirit rebirth or a white flag for all beef-seekers? Who knows, it worked either way, and as of 2022 Love’s fam remains untouched, while Prince continues to run the legendary Rap-a-Lot records.

In early 2019, a near-symptomless Bushwick Bill was diagnosed with Pancreatic cancer, a condition that rapidly progressed to Stage 4, calling for intensive chemotherapy. The remainder of the group immediately began to publicize a farewell tour, titled The Beginning of a Long Goodbye, The Final Farewell (which was actually announced without notifying Bill), partial proceeds of which were to be donated to pancreatic cancer awareness. The tour was canceled weeks before its kickoff however, and on June 9, 2019, Bushwick Bill died at age 52.

Only hours before Bill’s death, Scarface had announced a run for Houston City Council, proclaiming “Scarface is dead…I’m not going to be a 75-year-old rapper, I’m going to be finishing my last term in office as president when I’m 75”. Despite good intentions he bombed in the election and retreated from the public eye, then the following spring, contracted severe Covid, consequent dual pneumonia, kidney failure and a fever above a hundred which left him on dialysis and soliciting his 240,000 Twitter followers for a replacement kidney — to no avail.

(Update: As of May 16, 2022, Scarface has again reversed course and will be touring solo this summer under the banner “Farewell Tour.”)

After the Geto Boys dissolution, Willie D flew below radar with occasional guest appearances on tracks for fellow southern hip-hop legends Rick Ross, Young Buck and Bun B, before running into legal trouble in 2009. Convicted of federal wire fraud for operating a front company on Ebay that sold iPhones to customers overseas without fulfilling a single order, Willie pled guilty and spent one year in Texas correctional facilities.

Upon release, a changed Willie became a Fifth Ward community advocate—throughout the last decade he ran for public office, spoke at youth facilities, high schools, and universities, while penning an advice column for Vice Magazine. By late 2021, having established a rep as a seriously sharp-dressed street intellectual, Willie was hired by Saitama, one of the world’s fastest-growing crypto platforms, as President of NFT Curation and Talent Acquisition, for a reported but unlikely $50 million.

As for the collective remnants of the once hellhound Geto Boys, Wille and ‘Face currently co-host the remarkably placid podcast Geto Boys Reloaded. Serving as a major told-you-so to Dan Quayle (currently Chairman of Cerberus Global Investments) and Charlton Heston (currently proselytizing rappers in the afterlife from atop a wobbly Mt. Sinai made of illegal bullets), the series addresses cultural issues with infinitely more order and intellect than early Geto Boys societal bombardments.

Hey, even madmen mature.

Post Script

As it does over time, society’s definition of offensive has changed considerably since 1990; this time the internet has supercharged the change. Continuous easy access to offensive media has rapidly widened our definition of socially acceptable, and made being offended a near-normal experience.

In line with the early-90s societal reaction, this should equal even more elected officials fighting even harder to defend our nation’s moral fiber, but that groupthink shit is done. The same tier of politicians that once suffered stress-strokes crucifying Geto Boys in the name of national purity are now too busy eviscerating one another with partisan politics and real lies.

Advising parents is well over, now that music as ripe as the Geto Boys’ — once harder for young teens to get their hands on than nudie mags and smokes — can be located online within seconds by anyone, and corporate labels that refused to issue “indecent” releases now pay the bills with them.

Major media, once demonizing rappers for simply talking about murder, now offers free streaming slayings, in color, on demand. The NY Post site’s headline “Chilling video shows shooter open fire on sleeping homeless man” shows just that. And one scroll down, “Video shows man slashed during sidewalk dispute.” Yes, again.

Music videos have gone off the rails as well. Yes, in 1991’s “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” video, the Geto Boys do jump out of a tree and beat up a paid extra, without warning him. But in the 2016 video for his song “Truth,” Washington D.C. rapper OG ManMan dances on the grave of a real-life murdered rival while waving semi-automatic weapons, rapping “rest in piss” and pouring champagne -– later said to be his urine -– on the headstone. (Two months later ManMan was shot dead. As they say, live by the AR-15 and all that…)

Upon its debut, the “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” video was scorned by religious purists and lobbyists, with politicians calling the song absolute moral poison. After OG ManMan’s death, his “Truth” video was (and still is) celebrated and laughed at in comment sections across social media — while being completely ignored by the same church-and-state that once sought to illegalize Geto Boys.

As for the other pioneers of the gangsta rap pestilence, society has forgiven and forgotten. Schoolly D is currently a 59-year painter whose coveted Basquiat-does-Lichtenstein style artwork can be found on Sotheby’s auction block.

Once surrounded at a show by 200 police officers, before being arrested for performing a song they didn’t like, N.W.A.’s Ice Cube went mainstream Hollywood, acting in, producing or directing over 40 major studio films and network shows (including a 2014 Sesame Street guest spot alongside Elmo. Sesame Street!)

Ice T, once vocally in favor of murdering cops, has spent the last 22 years playing one on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, a show that rates extremely high with the same demographics that once wanted his throat.

And as part of the single, most drastic instance of societal reapproval experienced by any gangsta in history, 64-year old Ice can currently be found on grocery shelves, pictured on Cheerios boxes in a wind suit with a whistle, labeled a kids’ “Health and Wellness Coach.”

It took a 30-year PR rebuild — or maybe just 30 years — to score a spot on that cardboard, and this time around, it seems Ice will have no misunderstandings.

Speaking about the title of the reunited Body Count’s Carnivore album, he told Loudwire, “It’s basically: ‘Fuck vegans.’ We figure, anything carnivorous pretty much kicks ass….Everyone’s so pussy right now. We’re carnivorous!”, before clarifying, “But I mean, I’m not [really] saying ‘Fuck vegans.’”

Leave a comment