It’s difficult at times to drive around Seattle and not recognize the ultramega imprint that Chris Cornell left behind on his hometown. At least it is for me. Even for a city that’s widely known for ruthlessly tearing away and repurposing its own history in the name of “progress” – think bigger, taller, glassier high-rises as far as the eye can see – Chris’s fingerprints are everywhere.

Rolling down Leary Way in his old, childhood stomping grounds around Ballard, you’ll pass triangular-shaped Reciprocal Recordings, where Soundgarden recorded their debut album Screaming Life in 1987. Studio Litho, where they laid down their final, pre-breakup record, 1996’s Down on the Upside, nearly two decades later is only a couple of minutes further up the street, across from the massive statue of Vladimir Lenin. Ray’s Boathouse, where Chris worked as a young line cook scraping out fish guts to fund his rock star dreams is about 10 minutes in the other direction.

Across the sound in West Seattle, Cornell’s visage pops up all over the place. Most prominently, it’s muraled on the side of Easy Street Records. Right next to him, memorialized on brick is a similar piece of street art depicting his former roommate, and Mother Love Bone frontman, Andrew Wood. Inside, the shop is a veritable grunge rock museum, where you can pick up his near-entire discography, in vinyl and otherwise.

On 8th Ave., there’s the stately Paramount Theater which Soundgarden rocked in 1992 for their acclaimed “Motorvision” shows. Downtown, on 4th Ave., you can peer through a dusty window, and gawk at the remains of Bad Animals Studios, where he spent months and months and months honing the sounds on his band’s blockbuster 1994 album Superunknown. Two blocks over, is the Moore Theater where Soundgarden recorded their second EP, FOPP. The international headquarters for Sub Pop, the record label he helped legitimize all those years ago, is only a few dozen feet away.

Down on 2nd Ave in the alleyway is Black Dog Forge, where he and Soundgarden and Pearl Jam all rehearsed in the early ‘90s. Over on 1st Avenue, is the Central Tavern, one of the oldest saloons on the entire West Coast, and the scene of dozens of Soundgarden gigs throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. The band also used the upstairs as their own private business headquarters for several years. The Showbox where they reunited in 2010 as Nudedragons is a few miles down the road, across from world-famous Pike’s Place Market.

And finally, there’s his bronze statue set just in front of the Museum of Popular Culture, right around the corner from the Space Needle, waving to passersby for all eternity.

“His songs and voice ignited the alternative rock scene and helped put Seattle on the map as one of the world’s great music scenes,” the plaque around his feet proclaims. “Cornell’s work…greatly impacted popular music and will continue to inspire future artists and bands for generations to come.”

Whatever your feelings about the supernatural, it’s pretty much a fact that some parts of who we are inevitably remain behind long after we’re gone. They could be physical reminders – a painting, a bronze bust, a well-placed photograph – but there’s also an emotional imprint that’s much harder to quantify. A feeling. A collective memory. A tingling sensation when you hear a particular song at the right time of day.

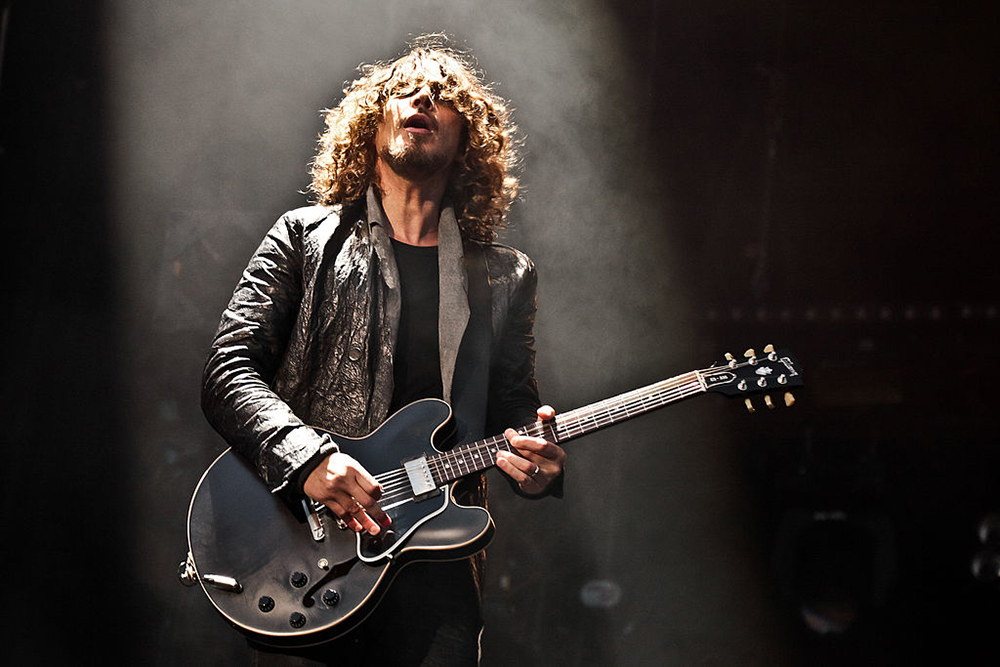

The wake that Chris Cornell left behind is especially immense because the impact he made upon the world was so incredibly enormous. As was the shocking nature of his death. When much of the world went to sleep on the night of May 17, 2017, one of the greatest voices in the history of rock was onstage at the Fox Theater in Detroit, doing what he did best; entertaining thousands of worshipful fans with his singular gift. The next morning, he was gone.

For many people, myself included, the tragedy was nearly impossible to reconcile. For those who knew him best – his family, his closest friends, and his many bandmates – it will forever remain so. Cornell was a larger-than-life person, in both word and deed. He was a 6’3” high school dropout, who fashioned himself into a poet. A self-described music nerd, who became one of the coolest figures in an industry where cool is the coin of the realm. A reclusive drummer, who moved from the rear of the stage to the very lip and then beyond, while transforming himself into the perfect idea of what a rock and roll frontman is supposed to look, sound, and act like.

“He was a really good drummer,” Soundgarden’s guitarist Kim Thayil told me in 2018. “He’s not like Matt [Cameron] but he wrote great as a drummer. I think so much so that [bassist] Hiro [Yamamoto] and I entertained the idea of getting another singer so that Chris continued to write with us on drums. But Chris really wanted to get up from behind the drum kit.”

Many in Seattle’s underground seemingly sneered as he extravagantly ripped his shirt off night after night and dove headlong into the crowd throughout the ‘80s. At a gig at the Central a few years back, Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic was onstage reminiscing between songs, when he called that particular move going, “The full Cornell.” Apparently, they used to take bets on how long the shirt would stay on. As the locals joked, others around the world took copious notes, learning from the dynamic, dark-haired frontman just what’s necessary to keep the roiling masses engaged.

But while anyone can buy a gym membership and do a few stage dives, one thing that couldn’t be replicated from Cornell was his iconic, medulla-scrambling voice. It was a singular instrument that stood out even among the amazing crop of gifted screamers that emerged alongside him throughout the alt-rock era. Even more astounding were all the myriad ways in which he used it. Chris Cornell wasn’t born a great singer. He had the natural tools, but it took him years of hard work and practice to realize his fullest capabilities. But once he did, all bets were off.

I remember I was talking to someone once while writing my book, Total F*cking Godhead: The Biography of Chris Cornell. They said they were having difficulty once while trying to figure out *how* to sing a particular piece of music. They were stumped. Befuddled. Could not nail it. Then a thought crossed their mind: “How would Chris Cornell sing this.” Suddenly everything became clear. They knew exactly what they were supposed to do. Chris gave them the roadmap.

There wasn’t a lyric on Earth that he couldn’t fill with heart-ripping emotion, stultifying power, or sheer, breathtaking electricity. His low, foreboding rumble could seemingly drop all the way to the depths of the ocean floor, before shooting up into the stratosphere like a F-35 screaming after a recently fired missile. When Chris Cornell stepped to the microphone, everyone took notice.

About four years ago, I was sitting with Kim Thayil backstage at the Metro in Chicago, talking about Cornell. He made the observation that “he didn’t carry a lot of things or materials or relationships within his life. He was a little bit independent of that. He traveled lightly.”

And it’s true.

Chris was always moving on to the next thing, and then the next thing, and the next thing. Sub Pop to A&M Records. Screaming Life to Superunknown. Soundgarden to Audioslave. Hip-hop beats to solo acoustic tours. He was always searching. Always looking around the next corner to find what interested him most. And then he was gone.

But for as light as Chris traveled through life, the legacy he left behind remains enormous. It’s in his children, who have taken up his craft and fashioned themselves into spectacular singers in their own right. It’s in the old haunts around town, and the memories of musical conquests left behind. It’s in the hearts and minds of the millions of fans who turned to his words and melodies in times of trouble, in times of sorrow, and in times of self-doubt. For as long as his records remain, they always will.

Chris Cornell may no longer be with us, but he’s always there.

Leave a comment