A version of this article originally appeared in the March 1990 issue of SPIN. In honor of The B-52’s announcing their farewell tour, we’re republishing it here.

December 29, 10:15 pm. The stage lights are all the colors in the B-52’s rainbow: housedress orange, linoleum yellow, jellybean green, oxygen blue, posey purple. Three microphones stand at the lip of the stage, in front of which the dance floor of San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium throbs with fans screaming and stomping for an encore. The crowd is a mixture of old-fashioned B-52’s fans—girls in 1950s dresses and beehives, shy-looking guys in polka-dot shirts buttoned up to the top, the occasional lobster brooch or pickle handbag—plus new fans picked up since the release of album Cosmic Thing, and a few skinheads and thugs.

The heavy, sweaty air stirs and an otherworldly organ whine rises above the audience roar. The stage lights change to infrared. One by one the B-52’s slowly file onstage for an encore. Fred Schneider, Cindy Wilson and Kate Pierson take their places at the mikes; hidden in shadows, guitarist Keith Strickland hits the Peter Gunn-ish riff of “Planet Claire,” from the band’s notorious debut album, and the roar turns to thunder as 9,000 people simultaneously start to shriek, shake and shimmy. A wide circle clears in front of the stage for slamdancing skinheads. Nearby, a fist fight breaks out between two surfer dudes. As the music builds, one throws his fist, staggers with the force of the follow-through and contorts his body wildly in time to the music as his lips, in perfect synch with Fred Schneider’s voice, form the words “Planet Claire.”

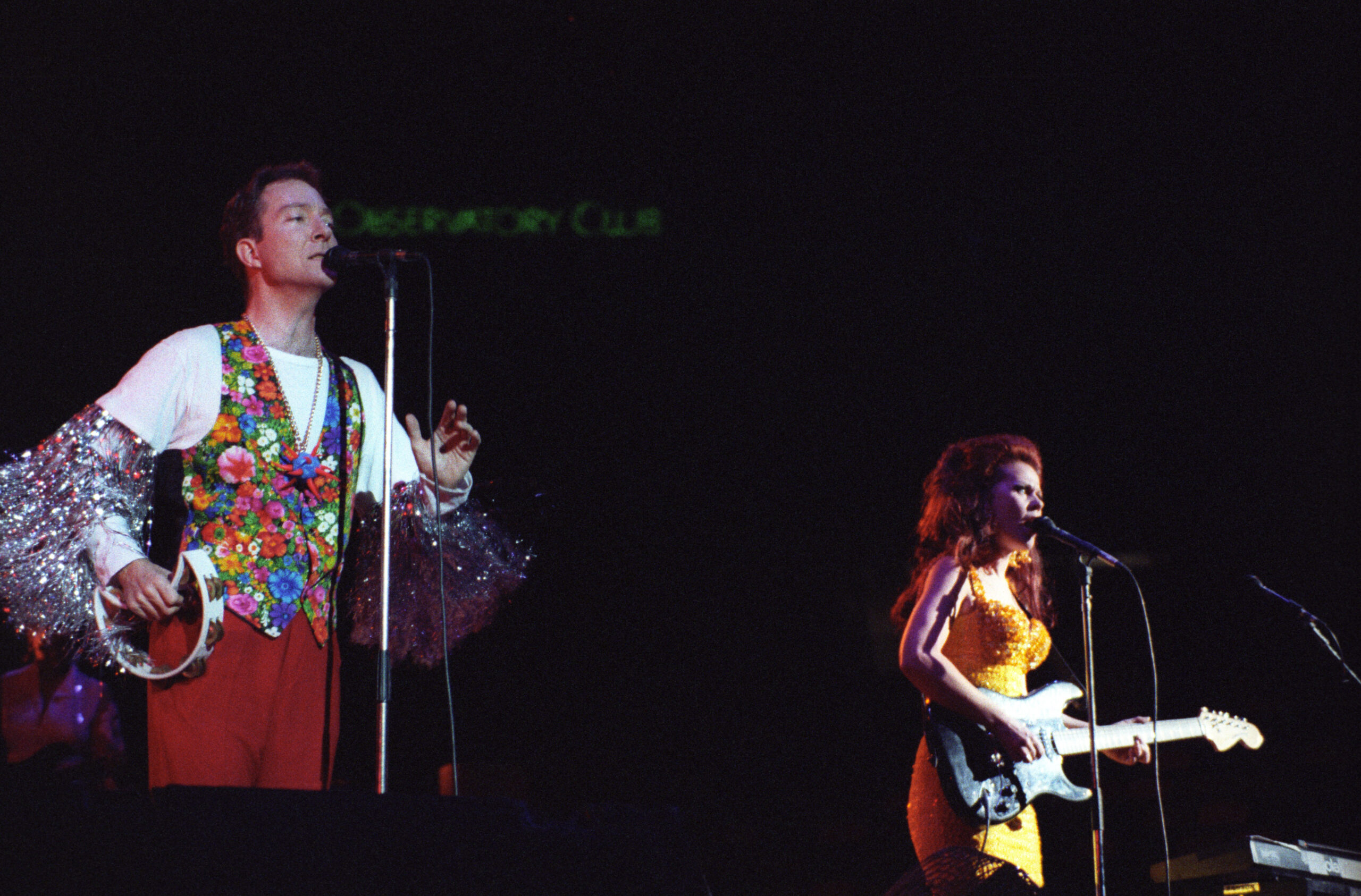

Welcome to the Cosmic Tour. Onstage, Fred stands motionless and issues lines in a robotic monotone. Kate, wearing a black body stocking plastered with giant primary-colored flowers, her hair teased into a sunburst auburn poof, dances like a hellion behind her keyboard. Cindy’s blond ponytail hairpiece flaps across her chest as she does the pony. Behind them, Keith Strickland, in penguin tails and a black top hat adorned with neon curlicues, yanks lunar leads and clamoring rhythms from his guitar.

B-52’s concerts haven’t changed much in the decade since their first album. The show has reached a greater scale than ever before—the band has gone from small clubs like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City in the late 70s and early 80s, to three nights at Radio City which closed the last leg of the Cosmic Tour—but the crowds lose themselves in the same ecstasy. And unlike most bands who reach a new, larger audience, the B-52’s following is, perhaps, more enthusiastic than ever about the early material. The album Cosmic Thing, the band’s first bona-fide hit (it’s now close to double-platinum) contains a couple of songs that send the audience into a frenzy—the hyper-zooming title track, and especially the single “Love Shack,” which went gold and hit #3 on the pop charts. But the response to B-52’s classics like “Planet Claire,” “Give Me Back My Man,” “Private Idaho” and “Strobe Light” is beyond bacchanalia. And when Fred screams, “Down! Down!” in “Rock Lobster,” which follows “Planet Claire” in the show, 9,000 people simultaneously squiggle to the floor. These songs, from the band’s first two albums (1979’s The 13-52’s, 1980’s Wild Planet), have not only kept a loyal audience coming to shows; they’ve carried over to an entirely new generation.

And yet, a lot has changed. For the first time, the band is touring with a bass player (Sara Lee, formerly of Gang of Four), as well as an additional guitarist/ keyboardist (Pat Irwin, once of the Raybeats). New York drummer Zach Alford has taken over on drums, now that Keith Strickland is full-time on guitar. Cosmic Thing is a departure from previous B-52’s albums, though, in more than the fact that it’s the first album since Wild Planet to be recorded only with live instruments. Sensitive, at times elegant, it’s the first B-52’s album where you don’t need to get the joke.

For a band long associated more with wild wigs and funny clothes than with serious music, Cosmic Thing comes as a watershed, a work of depth and “Topaz” and “Dry County” have an airy melancholy, a mood that’s at once sad and hopeful, like having the doldrums on a beautiful summer day. Even the more upbeat tracks—”Roam,” “Cosmic Thing,” “Love Shack,” “Junebug,” “Bushfire”— have a subtle timbre of pensiveness and longing. Throughout, the lyrics are more direct and descriptive, less humor-dependent than in the past. The words and music speak louder than wigs and kitsch.

But most importantly, the shows in the wake of Cosmic Thing are the first since original guitarist Ricky Wilson, brother to Cindy, died of AIDS in late 1985. The B-52’s have always been very close. No one is replaceable. Cosmic Thing almost didn’t happen.

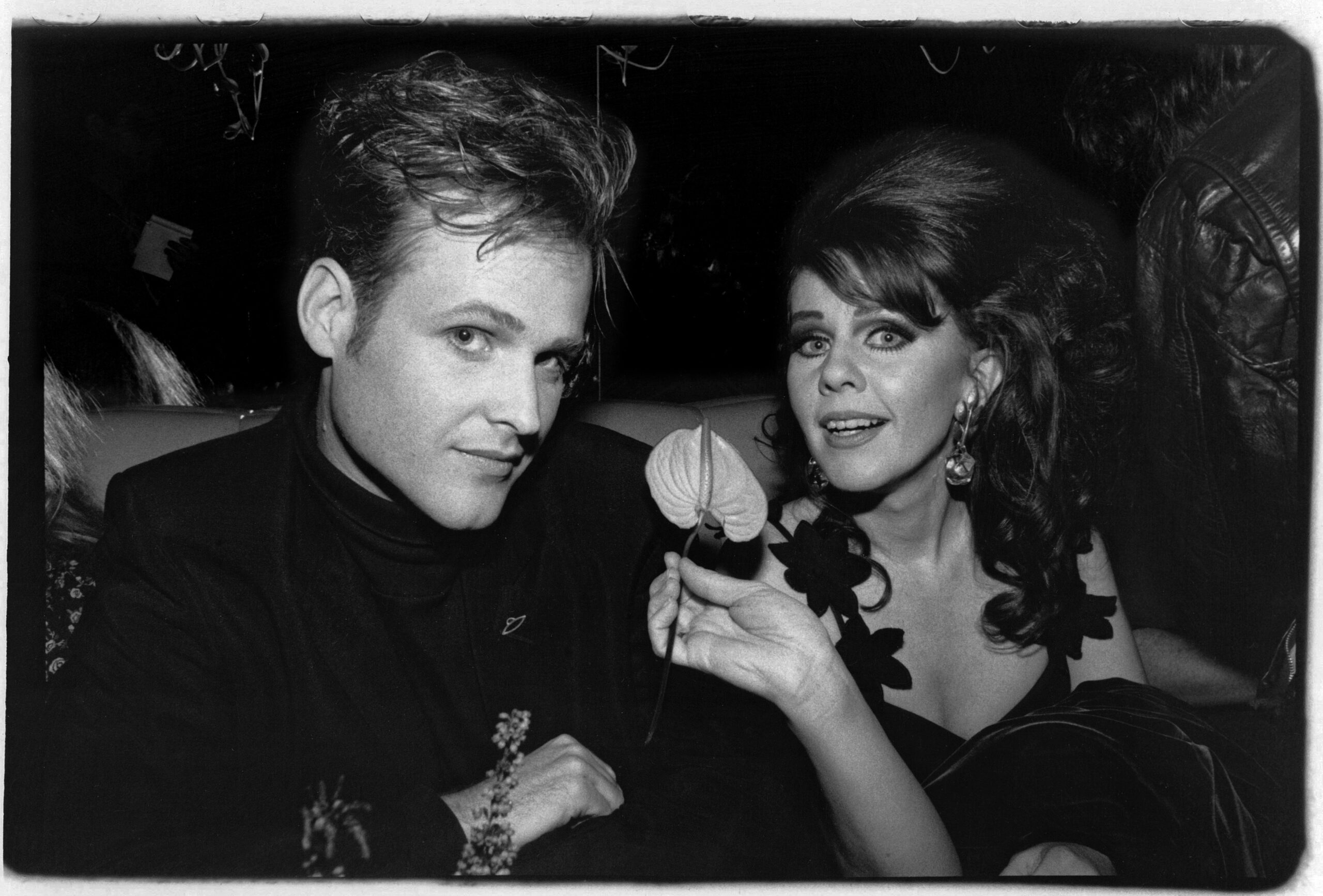

December 30, 2:15 pm. Keith Strickland sits in a European-style cafe on Columbus Street in San Francisco. He wears heavy dark shoes, jeans and a blue jacket with slightly torn lining. Onstage, his hair is sprayed into long spikes that poke out from under his top hat, framing his face like the bars of a cage; but today his hair is brushed back under a blue cap with rainbow stripes under the brim. Keith is soft-spoken, gentle, the backbone of the band in contrast to its three more boisterous frontpersons. He has a beautiful face, without a single age line despite his 36 years.

Keith, perhaps, worked more closely with Ricky than anyone in the band. They collaborated on much of the music, and he learned his eccentric guitar style (open tunings with strings in unison, often without the G-string) from Ricky, who was also the band’s principal arranger. They would present the music to the band, and Fred, Kate and Cindy would start jamming, spewing stream-of-consciousness lyrics at random from whatever the music conjured in them; sometimes they started with a title, and took off from there. It’s an extremely slow writing process; sometimes the band would have hours and hours of jams on tape, which they would then go through and edit, pulling together the best lyrics and melodic lines to make a single song.

No one could imagine the band without Ricky. “I always considered Ricky as a teacher,” says Keith. “I learned so much from him. I would come up with things on my own and he would listen to them. He was always encouraging me to write, so I really depended on his criticism. After his death, I didn’t have that confidence there. He always felt like the musical catalyst in the band. I mean, we all have a big part in what we do, but Ricky had this very special originality. He did a few songs totally himself, like ’52 Girls.’ It has a very unpredictable melody line, and that was very distinctive to Ricky’s style.”

Months went by. Keith stopped listening to rock’n’roll, concentrating instead on all sorts of different music—blues, Aaron Copland, new age. Eventually he began writing again, although not with the band specifically in mind. Occasionally Cindy or Kate would drop by his house and he would play them pieces he was working on. “The first thing I wrote after he passed away was the music that was eventually used for ‘The Deadbeat Club,’” he says. “That’s not the title I had for it then—it was called ‘There Is a River.’”

In the early days, he says, “we all used to sit around like this, just hang out, drink coffee and talk. It was sort of Cafe Society in Athens. It looked like we never worked or did anything, and friends of ours would say, ‘Oh, you’re such deadbeats.’ So we’d joke about ourselves being the deadbeat club. When I played the music for Fred and Kate and Cindy, everybody just started singing about the deadbeat club. That’s what the music evoked in them, when in a lot of ways that’s what I was thinking when I wrote it. And I didn’t tell them that I was thinking a lot about Ricky. They just picked up on it. It was very spontaneous. It’s really one of the most autobiographical songs we’ve ever done.”

Keith was surprised at how strongly the rest of the band reacted to the music, since he hadn’t considered it “typical” B-52’s music at all; it was much more introspective and laid back. Ironically, “Love Shack” had similar origins. “We did so many versions of that,” says Keith. “The first one was very lilting and melancholic, almost sad, very longing. We thought it was a little too heavy in that direction, so we did a different version—just kept going all over the place with it. When we were jamming in the studio, I just put on the drum machine and played bass guitar.”

At one point while they were jamming, Keith suddenly stopped playing. Cindy kept singing. She screamed, “Ti-i-i-n roof!” thinking the music was still going. Then she looked around, realized everything had stopped, and just said, “Rusted.” The band worked it into “Love Shack” ‘s final mix. “Collective subconscious really comes into play when everyone’s improvising,” says Keith. “‘Cause not one person is conceiving of this whole thing. It’s coming from five—in the beginning, five different points of view. There’s really no leader of the group, because we were a group of friends first, then we started the band. It would have been very odd if all of a sudden someone had said, ‘Well, I’m the leader,’ or, ‘You be the leader.’ Friends don’t do that. You all work together.”

Though Ricky’s name appears nowhere on the sleeve, the band feels he is an important part of the album, “just in the sense of having established the way we work, and his musical sensibility being so infused into what we do,” says Keith. “We were all very much a family. And of course, without him, we just wouldn’t be here today. He was definitely a part of this record, in a funny sort of way.” He pauses. “Not a funny way. That wouldn’t be the right way to say it. He’s just part of this record. His spirit’s still with us.”

The B-52’s first played together at a friend’s party in Athens, Georgia on Valentine’s Day of 1976, but the origins of the band go back much further. Keith met Ricky in high school in Georgia around 1970. “I went up to his house, and he had this two-track tape recorder, and all these songs,” Keith says. “The songs he had written were quite original and quite good. He had a very original sense of melody and arrangement.”

The pair immediately struck up a friendship and began writing songs together. At that time, Athens was just catching up to the hippie era, five years after the rest of the country. While there was always a strong conservative element in the town, there was also an openness to oddity that resulted from the town’s artist community.

Keith and Ricky were at the fringe of the fringe. They hung out together, played in bands together, caused trouble together. Robert Waldrop, a close friend of the band since these early days and the author of the lyrics for “Roam,” “Hero Worship” from the first album, “Dirty Back Road” from Wild Planet, and others, spied them at a Captain Beefheart concert in 1971: “They used to really dress wild,” he says. “You’d see Keith in the middle of the day walking down the street. He had really long hair and it was all teased out, and a shiny silver jacket, and high black boots. And, like, those big round mirrors from 18-wheelers—he would wear those as a brooch.”

Around that time, Fred Schneider had left his home on the Jersey Shore to go to forestry school at the University of Georgia in Athens. “One of the things I liked to do in college was wear clothes that totally clashed,” says Fred. “Orange shirt, lime-green and purple pants, brown shoes—just awful stuff. I would dress like that when I went out, too. I’d be dancing and hootin’ it up, and laughing, not takin’ anything serious. Then I met Keith and Ricky. They lived in town, but they were sort of among the wilder element in Athens. We just hit it off—I was a weirdo, they were weirdos. Kindred spirits.”

Fred joined in the musical collaborations: Keith and Ricky would play different instruments and Fred would recite things off the top of his head. “They were in lots of far-out bands,” says Robert Waldrop. “Extremely experimental. They were really talented, and completely self-taught.”

Kate Pierson moved to Athens in the mid-70s, and soon Ricky’s little sister Cindy was old enough to tag around. They had no intentions of forming a band, but that first show in 76 was, says Waldrop, “magical. I’m sure it surprised them that it sounded so good. They did ‘Rock Lobster,’ ‘Dance This Mess Around,’ a lot of stuff that ended up on that first album. Everyone just went wild. I threw my leg out. That was a good dance party.”

By 1979, they were gigging regularly around New York City. “We cheated a lot,” says Cindy. “We used to bring our friends up to New York and whoop it up.” But there’s no doubt that New York loved them. Early fans the Talking Heads offered encouragement, and the band got a management deal and a record contract with Warner Bros.

The debut album sold 500,000 copies without a scratch of commercial radio play (it has since gone past the platinum mark). In 1980, flush with success, they decided to move out of Athens. With three days to find a house and rehearsal space before leaving for Japan on tour, the band bought a place in the isolated upstate New York town of Mahopac. Wild Planet, which contained material mostly written around the same time as the songs on The B-52’s, was released to astounding acclaim.

But from the time of the move to Mahopac, the band began to lose some momentum. “It was a big house, we had plenty of room, but it was like we were in exile or something,” says Keith.

“More like a low-security institution with five inmates,” says Fred. “The whole community realized that a rock band had moved into the neighborhood, and they thought there’d be these wild things with tons of girls over all the time,” says Keith. “Our next-door neighbor was a retired lawyer, and we had to continuously fight him in court to allow us to build a studio.”

“We got sued for years by the next-door neighbors just because they didn’t like men and women living together in the same house,” says Cindy. “It was really strange. They thought we were the evil plague coming down.” The band stayed there for three years, during which they recorded the David Byrne-produced “Mesopotamia” EP and Whammy! “I think a lot of ‘Mesopotamia’ really reflects that isolation,” says Keith. “Like ‘Throw That Beat in the Garbage Can’: ‘The neighbors are complaining . . . ‘ Everybody tried to get rid of us.”

The B-52’s were also trying to experiment with their by-now established formula. Keith ditched the drums and he and Ricky brought in a drum machine; and Whammy!‘s “Song for a Future Generation” was the first song to include all five members singing lead.

In 1983 they sold the house and moved to New York City, but internal and external pressures were creating divisions within the band. By the time of Bouncing off the Satellites, things had gotten to the point where the usual method of writing through jamming no longer worked. “We had been together a long time, and we were still friends, but we had been falling apart a bit as a group,” says Fred. “We decided that everybody should write their own songs. I came up with ‘Juicy Jungle,’ Kate wrote ‘Housework.’ It was also a different album in that it had more serious songs.”

“We never did a straight, straight song,” says Cindy, “but we worked real hard to become more polished. ‘Summer of Love’ was a real positive song. Kate and I jammed with the music and wrote the lyrics and melody, but Ricky put it together. It’s ironic that when the album came out, so much awful stuff was happening in the band.”

Most of Bouncing off the Satellites had been completed with Ricky; no one in the band was aware of his illness until shortly before his death. After his death, they quickly finished the album, and it was released early in 1986. The band did their best to promote it, but no one’s heart was in it and there was no tour.

It was a year before the band made the decision to write together again, but little by little, they realized they could work without Ricky. Once they did start working together again, says Robert Waldrop, “it was this incredible healing thing.” Eventually they committed to making a record. Keith came up with music specifically for the band, like “Junebug” and “Cosmic Thing.” In April of 87, the group recorded the song “Cosmic Thing” with producer Nile Rodgers for the soundtrack of the film “Earth Girls Are Easy,” then set up sessions with Rodgers as well as Don Was.

Cosmic Thing was complete by early 89, and released in June. Though none of the songs are overtly about love, the word love recurs again and again, as in the chorus of Robert Waldrop’s “Roam”: “Roam if you want to / Without wings, without wheels … Roam if you want to / Without anything but the love we feel.”

Sung in Cindy and Kate’s clear, celestial harmonies, the song takes on a spirituality and sensuality beyond its surface significance of breaking through boundaries and following one’s own heart.

“There are definitely Zen overtones to those lyrics,” says Kate. “Robert’s really good at hitting the heart on these things. ‘Cause once you come out of that experience of total despair or separation, you realize that death is just part of the other side of it. Life and death are part of the same thing. It’s kind of liberating, in a strange sort of way.”

No one—not the band, not their management, or their label—expected Cosmic Thing to be the huge success it has become. Certainly the band’s intentions were modest. According to Waldrop, “I think they just really wanted to get it right this time.”

December 30, 7:05 pm. In San Francisco’s Four Seasons Clift Hotel, the spoils of a well-stocked minibar litter an otherwise placid room: chips, macadamia nuts, honey-roasted peanuts, a few empty bottles of Amstel. Fred Schneider is enthroned in a plush armchair eating sushi. He chews with great verve, quickly and thoroughly, as though he counts the number of chews before swallowing.

Suddenly, a woman screams:

“It’s an earthquake, y’all!”

Cindy Wilson bops out of the bathroom, followed by the rumble of an extremely loud toilet flush. It’s a few hours before the band’s second show in San Francisco. Keith Strickland is off relaxing; Kate Pierson is getting her hair done (it takes over an hour and a half to ply her dark-red locks into that voluptuous bouf), after her pre-show dinner of herbal tea, water, and fresh-squeezed juice. Kate thinks it’s a myth that our bodies need protein. She’s currently on a juice fast.

“She does that frequently,” says Cindy. “I’ve tried to fast, but I’m just not the type of person that can do it.”

“I’ve never tried a juice fast, ’cause I know if I’m in New York I’m gonna want a big pot pie or something,” says Fred between chews.

“I tried it once and got violently sick,” says Cindy. “All the poisons were coming out.”

“That’s a sign that you should do one,” tsks-tsks Fred.

“Let the poisons lie!” Cindy yells.

Except for Cindy, all the B-52’s are vegetarians and have been for some years. This goes part and parcel with their support of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and Greenpeace, both of whom set up booths at B-52’s concerts.

Fred admits he was a little overweight in college. “I was doughy. I didn’t lose the weight until I became a vegetarian. ”

“You know who else was chubby?” says Cindy, acting all coy. “Keith Strickland was a little porker.”

Shrieks of hysterical laughter.

“And I wore flared pants—” begins Fred.

“You’re dating yourself, Fred,” says Cindy.

“It doesn’t matter,” he retorts. “They called me a hippie. Just because I wore tacky ten-dollar Sears polyester bellbottoms.”

“You wore tacky Sears polyester bellbottoms?” cries Cindy, aghast. “Eeewww!”

“I had no taste,” says Fred proudly. He settles back and explains the origins of “Rock Lobster.”

“I was at this disco in Atlanta called 2001, this real tacky disco where every table was a lit-up Zodiac sign,” he says fondly. “I guess they didn’t have any money, ’cause for a light show they showed pictures of steaks on a grill, and lobsters and puppies and children playing ball—”

“Lobsters and puppies on a grill?” interrupts Cindy.

“No, not puppies,” says Fred, frowning, and resumes his story.

“Pictures of little children playing with balls, and lobsters and steaks—”

“Lobsters playing with balls?” asks Cindy. Shrieks of hysterical laughter.

Fred ignores her. “And rock lobster just sounded like a good title for a song. Ricky came up with the music, and I wrote the lyrics and Kate and Cindy came up with their vocals—”

“The squiddle-iddle-ops,” says Cindy helpfully.

“And spontaneously people made noises and came up with the shriek—”

“The Yoko Ono steal!”

“That burst of enthusiasm influenced by Yoko,” finishes Fred. “That was us in the essence, doing our first record.”

“It’s more like an art piece than a record,” says Cindy.

Fred sums it up. “We weren’t rock people. We just did our own thing, which was a combination of rock’n’roll, and Fellini, and game-show host, and corn, and mysticism. ”

December 31, 9:45 pm. It’s New Year’s Eve, and through the miracle of pre-recorded television the B-52’s are in two places at once: the Palladium in New York City, where they’re counting down the “Dawn of the Decade” for MTV’s New Year’s Eve party, and onstage in San Diego, where they’ll count down the midnight hour in front of 14,000 people.

Backstage in San Diego, the atmosphere is electric as the band prepares to go onstage. “Awright, let’s fuckin’ do it, man!” The drummer, in biker shorts and no shirt, drops to the cement floor to do a few pushups. The guitarist, also shirtless, jumps up and down and pumps his biceps. When they are all ready, opening band the Red Hot Chili Peppers disappear onto the stage.

As for the B-52’s, everything’s more or less in order. Fred nicks himself shaving with an electric razor, and Kate’s held up back at the hotel for an especially intense hairdressing session, but other than that things are running smoothly. Irish road manager Torn Mullally tries to give orders despite his ridiculous green party hat. Co-manager Steve Jensen has on an elaborate felt crown that looks like it was peeled off the King of Diamonds from a deck of cards. Jensen’s partner Martin Kirkup surveys the massive audience from behind the stage. “This is the future,” he says.

In the band’s dressing rooms, two enormous wardrobe trunks stand open, revealing a Crayola-box spectrum of fringe dresses, velvet hot pants, sequined gowns and speckled jackets. A pair of nylons is lazily draped over a stage coat embroidered with giant eyeballs. Off to one side is a wig case big enough to hold a bass drum. Cindy and Kate’s accoutrements could outfit the entire cast of the film “Hairspray.” Back on the East Coast, the atmosphere is much more hectic, and the band less relaxed. In a dressing room the shape of a circus tent, the hand waits for their cue from the MTV people as to when to hit the stage.

“Television is really nerve-racking,” groans Keith. At 11:45 pm New York time, the band goes out in front of a studio audience and an enormous MTV backdrop to sing “Dance This Mess Around” and “Roam.”

At 10:50 pm in San Diego, the band goes onstage and opens the show with “Cosmic Thing.” Fred has taken two party favors—a champagne bottle and an hour-glass—and threaded them with a ribbon to wear as a party hat. Cindy, in a slinky black minidress, struts the lip of the stage like a runway model, swinging her faux-pearl necklace as if it were a lasso. Kate darts around the stage like a wild thing whenever she doesn’t have to sing or plink her keyboard. Keith, the Mad Hatter guitar hero, stands on a pedestal next to a row of some twelve or thirteen guitars, all of which have different tunings.

Between the band’s own stage delirium, the rapturous response of the crowd and the heightened awareness of time that strikes at the passing of every new year, the San Diego show is close to magic. After ten years, the B-52’s truly have reason to celebrate. In an effort to explain the band’s ever-growing appeal, Robert Waldrop says, “The whole kitsch and party thing, that’s all surface stuff. I look at them, and I don’t even see that. They’re doing something between them all that’s just so honest, and hypnotic, and ecstatic. Not many people can get it to that ecstatic moment. And they do it. They don’t always do it, but they do it. Once people experience that, it’s the real thing.”

December 31, midnight. On the East Coast, multi-colored balloons drop from the ceiling to celebrate the turn of the decade. Freb grabs one and chases Kate around the stage, whacking her on the behind. Before the band goes into their globalized, New Year-ized version of the Beatles’ “Happy Birthday,” Fred says to the audience, “Be green, not mean, in 1990.”

At midnight on the West Coast, yellow and black balloons cascade onto the packed dance floor. Fireworks explode, bathing the arena in blinding white light. The band scrambles around the stage, hugging and kissing each other. After they play “Happy Birthday,” Fred tells the audience, “Be green, not mean, in 1990.”

And a new decade begins.

Leave a comment