Book Club is a new monthly series exploring the literature that inspires some of our favorite musicians. Whether it’s a music biography that got them through the slog of tour, the poetry collection that eked into their most poignant lyrics, or the novel that sparked a rock opera, we’ll get to the bottom of it so you can add it to the top of your book stack. This month, we speak to Damian Abraham from the band Fucked Up.

Damian Abraham is best recognized as the energetic singer of Toronto hardcore auteurs Fucked Up. But a quick glance at his extracurriculars—his long-running Turned Out a Punk podcast, his VJ gig for MuchMusic, his VICE TV documentary series about wrestling—are indicative of his unending desire to learn more about his world and its histories, and to soak up its pop artifacts. “The only reason I do Turned Out a Punk is because it’s like study for me,” he tells me on the phone (after I complain that I want to read all the books he’s recommending). “Every week, I walk away with a new bunch of stories to punish people who don’t want to hear them.”

On top of what he learns from his guests, Abraham’s gleaned a whole lot from his massive personal zine library, a lifelong project he hopes to catalog someday. “Organizing zines is one of the things that keeps me up at night,” he confesses. “I’ve tried to make it flow from eras: proto-punky type stuff into first wave punk stuff into ‘80s hardcore zines. The ‘90s is when it gets fucking amazing with zines, and you have the riot grrrl stuff and all the cool film zines.” Although he laments that a sleepy secondary market has relegated many zines and flyers to obscurity, he’s thankful for a few bound compilations that reproduce archives faithfully, like The Riot Grrrl Collection and Metalion: The Slayer Mag Diaries. “A lot of this stuff is impossible to find. To be able to flip through like, ‘Ah, that’s this Girl Germs cover!’ was completely invaluable. I love when they do a zine book where they do exact replicas of the covers or the pages.”

In celebration of the release of Fucked Up’s Do All Words Can Do—a rarities collection of David Comes to Life-era b-sides, compiled by Matador Records in celebration of the album’s 10 year anniversary—Damian tells me about the books that inspired him then and now, and answers an age-old riddle: how to organize a sprawling home zine library.

SPIN: What are you reading right now?

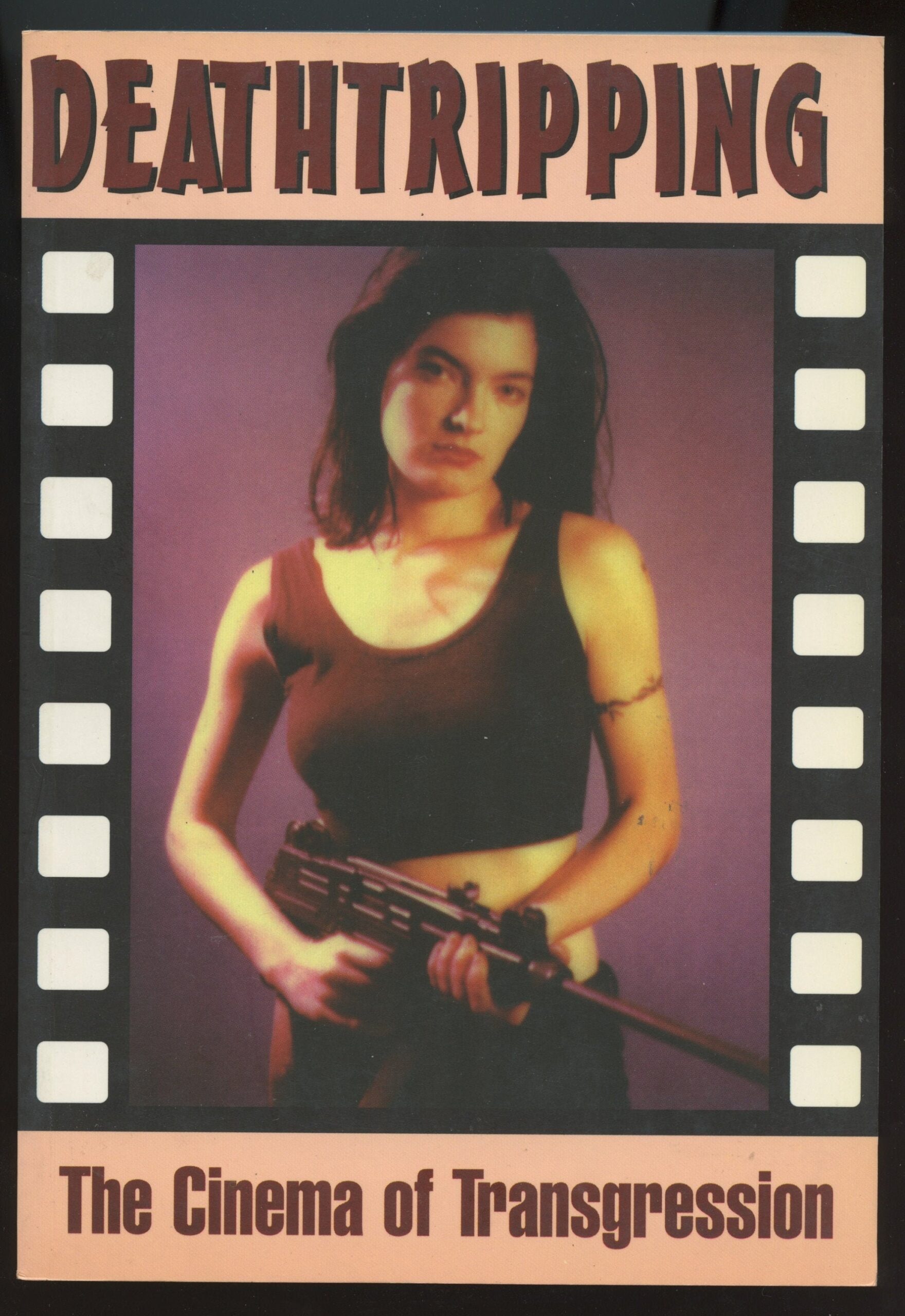

Damian Abraham: Deathtripping, which came out on Creation Books in the mid-’90s. It’s an academic thesis about Cinema of Transgression. I’m interviewing Kembra [Pfahler] from Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black in a couple days, so I’m trying to consume as much as I can about this world that I’m interested in. But only when you sit down and plug into an academic thesis do you realize how little you truly know about everything that’s going on.

On the last tour we just got off, I read a collection of speeches Noam Chomsky gave during Occupy Wall Street. A lot of it is very dated now, but there is a lot that’s still shockingly and frighteningly very relevant.

I wanted to ask you about Chomsky because I read you once played a theater where you went to see him speak. Do you read a lot of linguistics?

No, I’m a Chomsky poser. I got into Noam Chomsky from Propagandhi. For anyone who truly studies him, that’s like liking Blue Öyster Cult because of “Don’t Fear the Reaper.” But for a lot of kids coming out of this punk, indie background, that was such an accessible way to get introduced to not only Chomsky, but all the stuff Propagandhi were referencing—they had a reading list in one of their records. I keep up with Chomsky anytime I see a speech or am in a used bookstore and see a book of essays or speeches. He’s talking about real oppression, but the way he talks about it, there’s always a tinge of hope.

For your podcast, you’ve interviewed several musicians who’ve published books—Michelle Zauner and Jeff Tweedy were both guests. Do you have a favorite musician-turned-author?

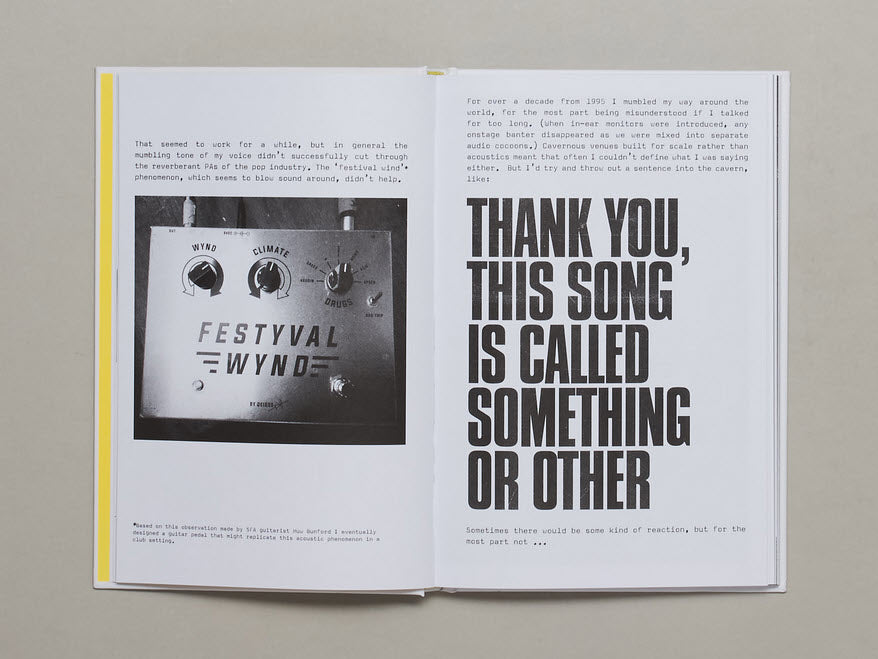

Yeah, Gruff Rhys. He put out a book last year [Resist Phony Encores!] that is fucking awesome. It’s a biography, but what he did reminded me of a Situationist text. Sometimes the text would take up the whole page with one word; the process of reading it is part of the book. I was familiar with his pre-Super Furry Animals music, and I knew he was connected to the second language punk scene in Europe, but I thought that book was phenomenal and took me completely by surprise. It was a really fun read.

You wrote the foreword for the Leftöver Crack oral history, Architects of Self-Destruction. What are your favorite oral histories?

The oral history is a much-maligned type of book, and I can completely understand why. Because Please Kill Me came first, that’s the definitive genre of punk history. My favorites are Gimme Something Better, which is the San Francisco punk book. That one is wild—there are stories about when a dead baby’s body was hidden at the Gilman. That’s profoundly upsetting, but there are also very exciting and interesting stories in the book. And Everybody Loves Our Town about Seattle; the early stuff about the U-Men was really interesting to me. A lot of them are incredibly problematic and there’s certainly editorializing that goes on that I don’t subscribe to, but there’s nuggets buried within that. A book like American Hardcore, some of these interviews with some of these people that will never be interviewed again because they’ve passed away…even books I don’t necessarily like, there’s still valuable information contained in there. Because as long as they’re not misquoting people, at least there’s these quotes.

Your home library was photographed for Loud and Quiet. Zooming in, I see a lot of political history—Canadian Working-Class History, The New Intifada. Are you reading any history lately?

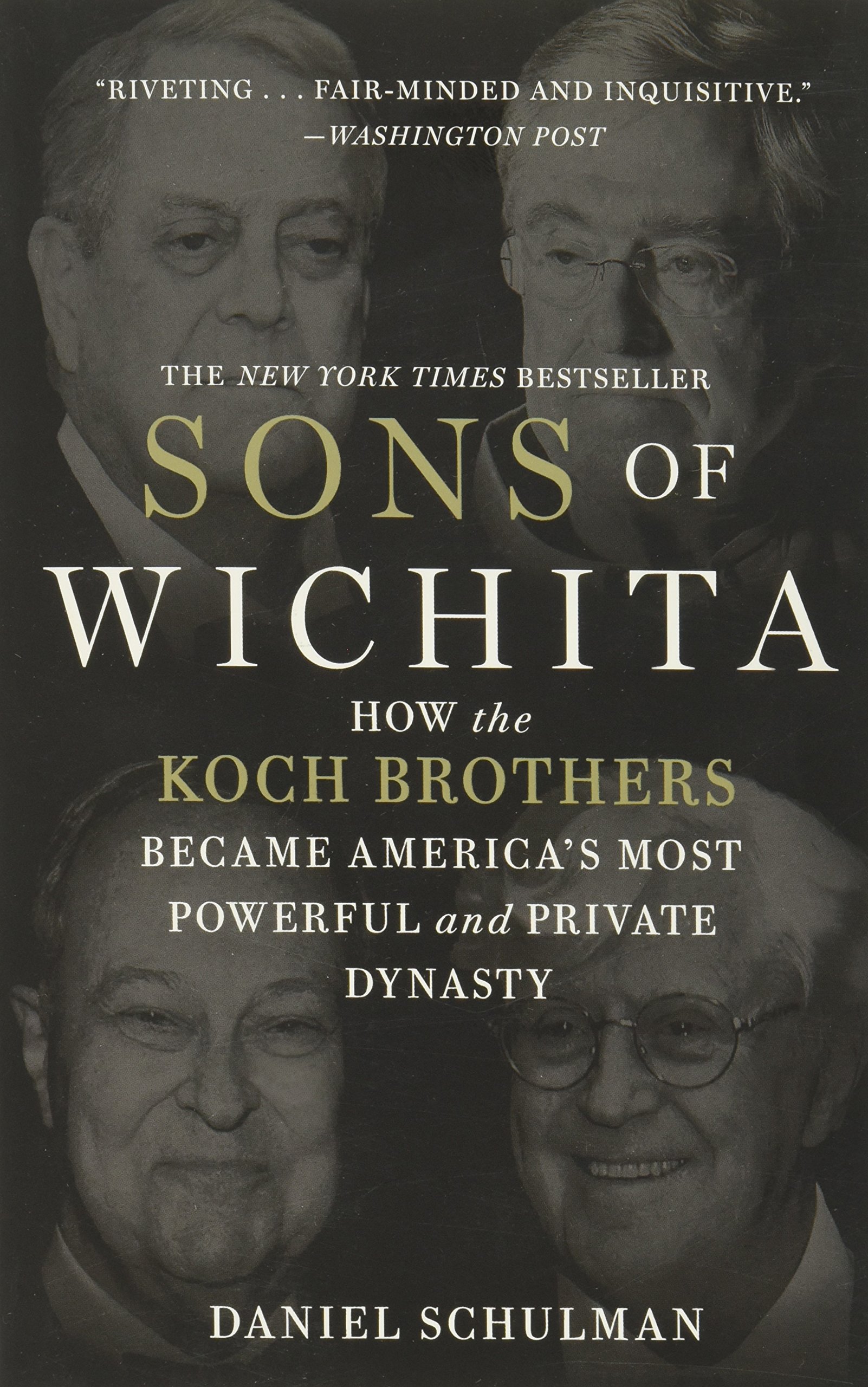

I grabbed this Sons of Wichita book at Powell’s on the last tour: How the Koch Brothers Became America’s Most Powerful and Private Dynasty. Once again, I think it’s outdated now, because it’s from a few years ago. But outside of the bad companies, these people are involved in, I never knew how their ascension happened. I didn’t know there were four brothers, in fact. I find that with a lot of stuff, especially outside of music, there’s a hole in knowledge for me, so I should try to fill it somehow.

Your writing around David Comes to Life was partially inspired by Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, and you were reading a lot of plays, right?

Yep. Because I was trying to put on the edifice of being into theater, I was reading a lot more stuff back then. I still really enjoy reading plays. I had a learning disability as a kid—I probably still have it—and too much text on a page freaked me out. On a weird, deep level, it’s still that way. Now that I’m thinking of all the books I like—oral histories, plays, even that Gruff Rhys book—it’s not all dense blocks of text. There’s breaks. I find it’s easier to follow that information.

You’ve been part of a few book events, including with John Doe, Don Pyle, and Sam Sutherland. What’s special about those kinds of events?

The thing that’s special about that is the energy. Let’s be honest: I have a small pond I play in. Most of the events I’ve been part of are for historical music books. Normally when all these people are in the room together, there’s a loud band competing for people’s attention. Now we’re all brought together by the music, but we’re here in a quiet space to listen to people talk. That, for me, is the most exciting part of it—to see live music, this thing that’s at times anti-intellectual in its presentation, given space to intellectualize.

Is there a book event you wish you’d been part of?

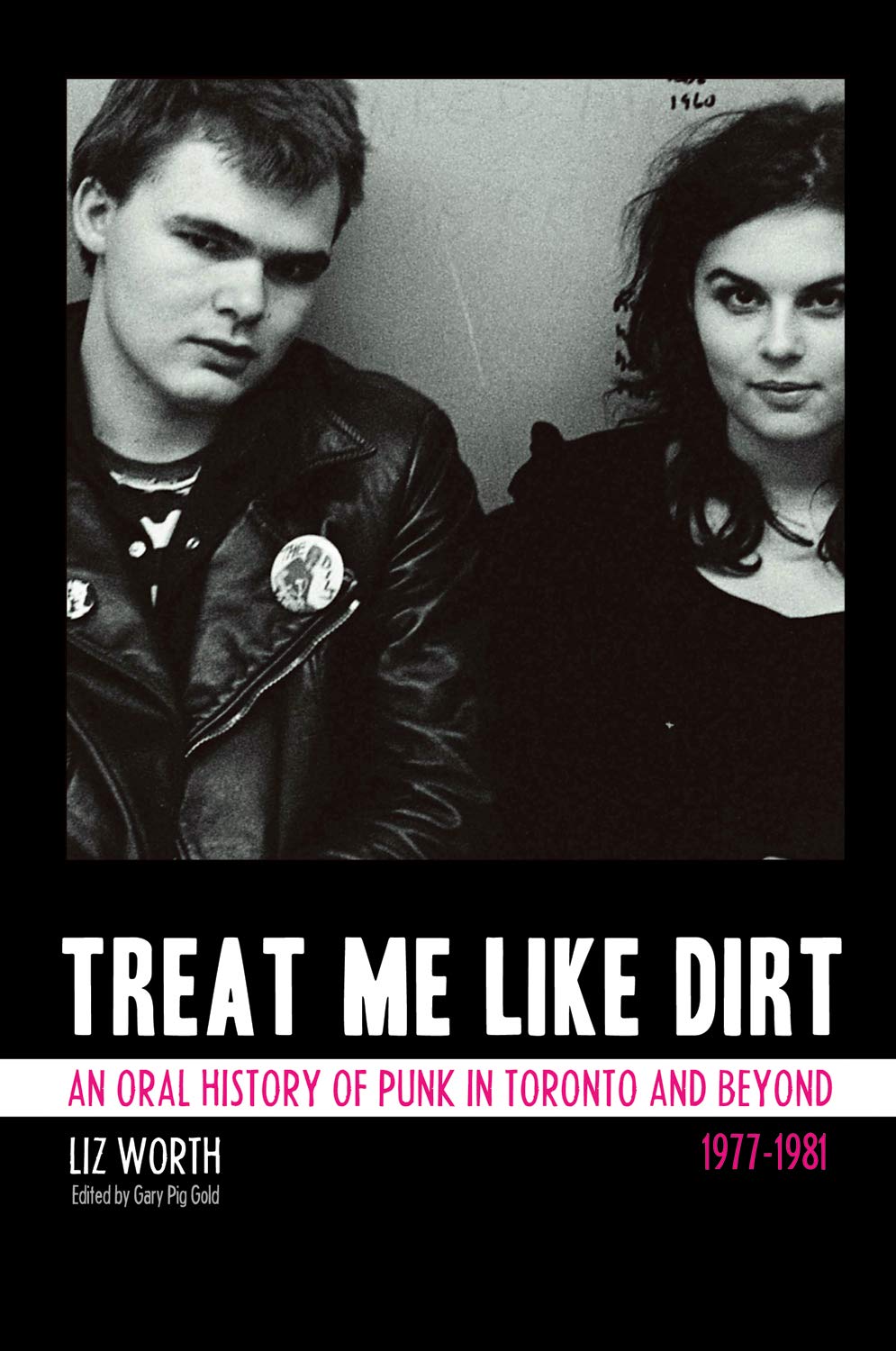

My dream event would be to be at the launch for the Darby Crash book, What We Do Is Secret [by Thorn Kief Hillsbury]. Because going through that book, there are parts where people are fighting with each other, and competing for space in the historical narrative. To see all those people in a room together would be so fascinating. I did the [release] for Treat Me Like Dirt, which is the Toronto oral history that an amazing writer, Liz Worth, worked on. Years she poured into this book to document these people’s histories. We were doing the book launch, and the amount of shit coming from the audience about who wasn’t covered, who should’ve been given more space in the book… there’s a guy they literally refer to as Mr. Shit. They were like, “You should have given more space to Mr. Shit!” I can only imagine how thankless putting out a book like that might be. But she’s thanked by me, because I get to read it. I was so grateful she put in the work, so I could sit there and learn and enjoy.

As thankless as writing these books are, my dream book to write would be the oral history of Mike Watt’s Ball-Hog or Tugboat? To me, it’s the record that ends the first alternative movement in the ‘90s. It’s post-Kurt Cobain passing away, but every single person you can imagine is on this thing, from God Is My Co-Pilot to the Beastie Boys. It’s everyone. There’s so many weird songs and weird personalities. Kathleen Hanna’s contribution is truly one of the most bizarre things I’ve heard—it’s a skit where she calls and leaves a message on Watt’s answering machine saying she doesn’t want to be on the record because there’s a rapist on the record. It’s very odd, and ages even worse than it did at the time, not to excuse any of that. But there’s incredible songs on the rest of this record. There’s one name on this record I never knew, Ronda Rindone. She plays bass clarinet on this free jazz improv song. At [my kids’] school, one of my dad friends comes over and is like, “You know who Ronda is, right? Ronda Rindone from Ball-Hog or Tugboat?” She’s my kid’s teacher. She moved here from L.A. after playing on this record. There have to be so many interesting stories. I just think this would make the ultimate book.

You gotta do the 33 ⅓.

Yeah, maybe it’s a 33 ⅓. I’m a very slow writer. I’m a slower writer than a reader. But this is what I need. Now I have to do it.

Leave a comment