“Your name comes up a lot around here,” I tell Johnny Marr during our virtual visit, me from the U.S., him on the outskirts of his hometown of Manchester, UK. He sits—smiling, warmly—in front of an enviable display of recording equipment, a far cry from the curious kid hanging around future Cult guitarist Billy Duffy’s teenage garage band, the youngster of the group.

“I’ve known Billy since 1975,” Marr explains. “He was older…he was very kind because you know teenagers. I was so young. I was probably about 12. Pretty precocious, I guess, or pretty intrepid. I used to just go where the guitars were. He was a kid, 15-years-old himself, but seemed very serious about music. It was great. He still treats me like some little kid, which is sweet, really, at this age.”

When I spoke with Duffy last summer, he mentioned giving Johnny his first amp. “I used to bug him,” Johnny says. “I bugged him and bugged him about this shirt, this pink shirt. He sold me my first amp for £15. When I got the amplifier home…what was sweet was that in the back of the amp, there was this pink, real punk rock Johnny-Thunders-kind-of shirt. He stuck the shirt in the back which was very sweet.”

All these years later, Marr says he and Billy stay in touch, and never forget their blue-collar roots. “As two older geezers, now when we meet up 40 years later, we’re like, ‘How did that happen?’ It’s cool.”

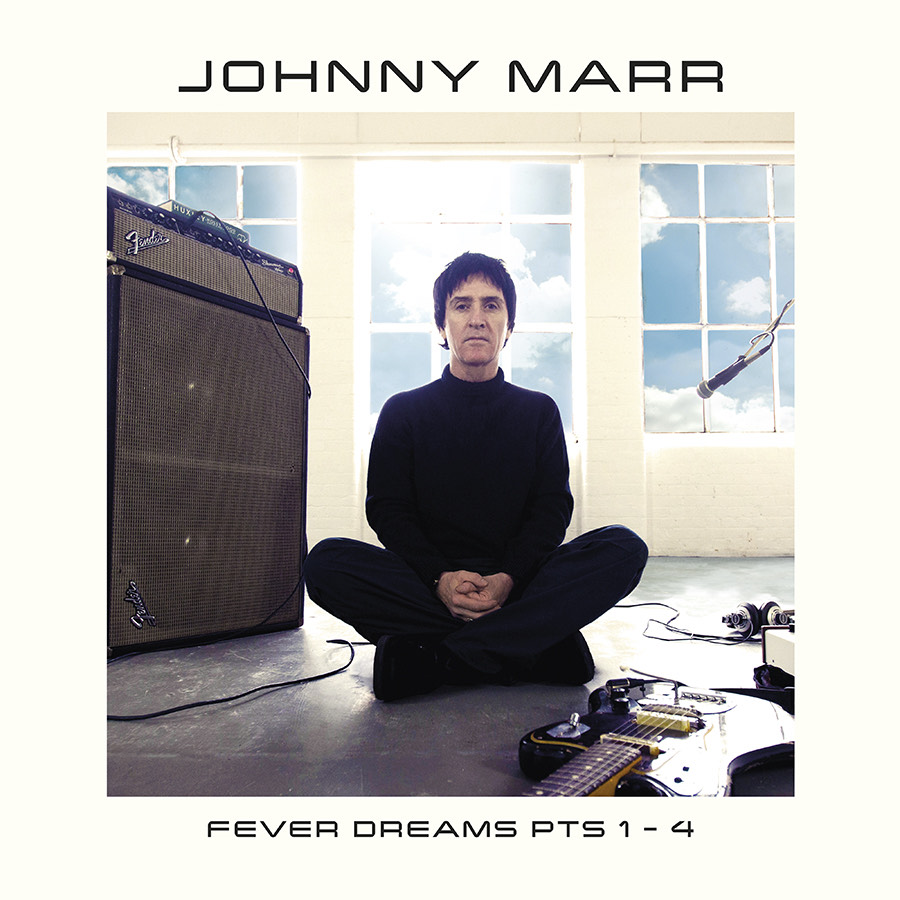

Aside from Duffy’s childhood neighbor, Johnny Marr is better known as the genius behind the sad/happy, all-too-relatable dichotomous sound of The Smiths, and, ever since then, one of the most influential alt-rock songwriters of our time. On February 25, he released his fourth solo full-length album, the 16-track double LP Fever Dreams Pts 1 – 4. Most recently, you may have heard Marr’s work on the No Time to Die James Bond soundtrack, alongside longtime collaborator Hans Zimmer, which included arrangements for the Grammy-Award winning title track, written by Billie Eilish and her brother Finneas.

Is there a secret to Marr’s artistic prowess? “No,” he says, glowing with humility. “I’m more concentrating on the next song I write just not sucking, seriously.”

We went on the record with Johnny about the new album, what inspires him these days, and why “nothing worthwhile is really that easy.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

SPIN: What was it about that neighborhood in Manchester that produced two incredible musicians like you and Billy Duffy?

Johnny Marr: We lived on the projects, but it was the biggest housing project in Europe, Wythenshawe, where we’re from. It was considered quite an edgy place. There was quite a lot of violent crime. The place that I moved there from was so much more edgy. When I moved to Wythenshawe, I thought I was in Beverly Hills.

I was like, “Mum, what’s that?” My mother was like, “That’s a tree.” I was like, “A tree? Okay,” because I lived in the inner city before that. To answer your question, there was a ton of kids there, just tons of kids. It was a thing where the kids from all over the inner cities– I think Billy grew up there, such as myself, we were all relocated to this place. For me, just for my subjective experience of it, moved there with my sister, who was 11 months younger.

I was running around chasing all her friends, and my friends were trying to get with her. She always reminds me, I was always staying with my sister. It was a great place to be a kid because even though it was a bit edgy, a bit lively, there was a lot of police there, being working class, the clothes were really important. The code of clothes, like what was going on every few weeks with different shoes, and jackets, and all of that.

A big part of it was music culture, this being the 1970s, so all about 45 records and what bands you like. It became very tribal. Of course, I arrived there already as a little guitar player because I’d started playing really as a little kid. Come from a very obsessive musical, large Irish family. My parents were very young, and to this day, in their 70s, really obsessed with music. Both my parents are real experts at Country & Blues and stuff like that. They know everything about who wrote every song.

I hit there just learning to play guitars, which is why I gravitated to Billy. I would go where I heard there was someone with a drum kit or older guys usually with guitars. I was really little. Even at 12, 13, I was little. Mostly, the older guys just didn’t even notice me, which was handy because I was watching everything all the time. I was pretty streetwise. I would hear about different bands.

Then I started getting a bit of a reputation…I could play “Rebel Rebel”, but no one else could play it. There were bands everywhere, loads of little bands. This was just before punk was starting. Older guys then would seek me out and say, “Hey, do you want to come and play with us? Do you want to join our band?” I would get on buses across town. You could get on two different buses and still be in the same project. I would go across town if I heard of some band who had a real Fender or something like that. Then, 35 years later, if I thought there was an interesting band that I could learn something from that would make me a better musician, I would think nothing of walking in there and go, “Okay, let’s see what’s going on.” 40 years later, that’s how I ended up in Modest Mouse as an adult. I end up in Portland, Oregon. Exactly the same behavior, walked into a room, strangers, mostly guys who’d knew I had a reputation. I was like, “This sounds interesting. Let’s see how it goes.” Then, I ended up being in an American band and living in Portland and that was 2005.

Sometimes, when I’ve had to explain why I’ve done certain things the way I’ve done it, it all goes back to the impulses and the journey or whatever you want to call it that I seem destined to do. It’s all part of my character really. I just always followed where I thought the good idea was.

Where does your inspiration come from?

Luckily for me, my focus is just really trying to do something great, like there’s stuff what I thought was great when I was a kid. It’s often a tall order. You often fall short, but you do okay along the way trying. Just promoting this record now and I don’t mean to sound too much of a baby about it, but the fact of the matter is really, look, I’m so all-in when I make records, particularly these days. I was always like this in whatever my role was, whether it was in The Smiths. Particularly with The Smiths because I formed that band and it was quite challenging.

Then, also, if you ask people who was in The The with me or you ask Modest Mouse or The Cribs, when I do stuff, my personal life, such as it is my private life, is always secondary. I’m very lucky that my wife has been my girlfriend since I was a kid, and my family, no one would have it any other way. When I’m making a record, I lock myself out of the house. I lock the keys in the house, I lock myself out. I prang my car. I lose my dog. My considerations are completely taken up with, “Why isn’t that chorus working right? Do I have to rewrite that? I just spent two weeks working on it. I’ve done that in the wrong key. I really need this word. This word is driving me crazy.” This is at 4:00 a.m.

“I’ve just woken up. I think I’ve got the chorus.” I have an amazing band. Everyone knows my band are great, but when I make my demos, they’re really pretty comprehensive. I play the bass and then I play all the keys and I program all the kit and all of that. It’s really like a big one-man-band thing before I even bring it to the guys. It just completely takes over my life. I never knew any other way of doing it and I’ve been doing that since 1983 I guess. Every album I make, I say to my friend who’s a writer, “I swear next time I’m going to do it different. Over the next year, I’m going to write three songs, and then I got to write two. I’m going to take a couple of vacations. It’s all going to be cruisy.”

He always says the same, “No, you’re not, dear. You’ve been saying that for 25 years. You know how it has to be.” I guess he’s right. I wish I could be like, I get up in the morning, maybe go to the gym, have some nice lunch. Go to the studio, go in there, tinker around for a few hours. Go and meditate and then phone my family, but it doesn’t really work out like that. I don’t know whether it’s the same with you with your work, but I’m awake at 3:00 a.m. with ideas, texting myself. I don’t know any other way of doing it really.

It’s great that it’s finally out. I don’t mean for it to sound like a chore because it absolutely isn’t. It’s completely self-imposed. When I make records, I go, “It’s time to make a record.” I don’t wait till I’m inspired. There’s no career-y thing. I guess, in some ways, my management could say, “You don’t need to make a record now for five years. You’re driving everybody crazy. Just play your hits.”

It’s a habit from the values that I had from when I started out with The Smiths. It’s like, “Right, now we need a new record. Now I need a new record.” Now, that leads me to where I am today, talking to yourself and just glad that it’s out. I’m obsessive about how I do it.

The truth is always more interesting. I wish it was easier for you.

I think nothing worthwhile is really that easy, I don’t think.

You have the voice in the back of your head. The same voice that says, “I really got to clean up my apartment.” With this album, when I started it, I started writing it before the pandemic, so I had no idea that the world was going to go into freefall. I just knew it was the time. I was excited about it. It’s always a mountain to climb and I go, “Okay when this is finished, I’ll be a little different.” I had the title and this voice in the back of my head was like, ” Okay, you sing about architecture sometimes and you sing about psycho-geography… and you usually avoid really singing about your own emotions.” Partly because I think I got sick of hearing everybody else doing it. I thought, “Well, Siouxsie Sioux, she seemed to do pretty well without pouring her guts out. Someone’s got to do it.” It turned out that going into this record, I realized that on every album, I did a song that I was like, “I’ve got to show a little bit of myself here.” I like all the clever stuff, but being a songwriter’s amazing because some music just demands that you honor it with something sincere. It won’t sound right otherwise. Now it’s turned out over the solo albums that they’ve been the songs, not surprisingly, that people like the most.

I thought, “Well, okay, I’ve got to learn from that.” I want to evolve. I want to get better. I want to be a better lyricist, I want to get better. I want do something I haven’t done before. I remember I was in this room and I was starting to write. I was thinking, “Well, okay, how do I do that, that suits me, that isn’t corny, that isn’t earnest, that is a way that I find interesting?” I was like, “The soul singers, Al Green managed to do it pretty well without [being corny]. He managed to do really, really simple, emotive music, emotive lyrics. Sing really well, it all sounds really good.” I was like “Oh, okay.”

Because I also like singing about the outside world in my own way and stuff, I thought, “Curtis Mayfield managed to do that pretty well.” I thought, “I certainly haven’t been involved with doing that before,” so that was exciting to me, trying– a little bit of an inspiration. That’s why Spirit Power and Soul sounds like a Curtis Mayfield title or Lightning People has got a gospel-y vibe about it. I thought, “Well, okay, I’m a Manchester musician from the post-punk era in the ’80s, maybe if I can bring what I felt was the language of song, that will help me be able to be more emotive and get across some of those sentiments in a kind of poetic way that sounds like songs. That gave me confidence to try and sing stuff that’s a little more personal, but without losing the poetic nature of it.

Writing songs is like that. It’s a really fascinating process. Often you set yourself up these puzzles and these conundrums and then you have to find ways of solving it. It’s good. That was the start of it and then you end up going for that and then it just comes out in your own kind of weird way, I guess.

What was the first song you wrote for this album?

The first one I wrote was “Hideaway Girl” and then I wrote “Ghoster”. I thought it would be a good idea if I was able to write a banger and I wanted it to be electro, like an electro track like Kraftwerk or something. It’s all very well having these good ideas, these concepts, but you can’t be too contrived because sometimes you have an idea and it just doesn’t come right.

I wanted the first single to be this banger. That ended up being “Spirit Power And Soul”. I had written the first two, but then I got the call to do the Bond movie. That interrupted the process. I went and worked on that for a few months. Then, as soon as I had finished, the Bond movie was wrapped up, then the pandemic kicked in. I had already started the record, the writing process. I wasn’t making a pandemic record, but then of course I wrote throughout that and you can’t help but sing about the things that are affecting you.

I had no intention of ever singing about vaccines or anti-vaxxers, or about the stores being closed, or whatever, but without a doubt overall because I generally sing about perceptions and about people and I think about my audience a lot and all of that. Inevitably, there are things that really do relate to having gone through this crazy fever dream. You know?

Can you tell me a little bit about the title?

Well, it was probably when I was running, because I think about what I’m doing a lot, like all artists. You can be walking towards your car or you can be pouring a juice or something and an idea just seems to drop down from the heavens. I was kind of like this when I was a kid, really, where plenty of them are just kind of musings, but you know when something taps you on the shoulder and goes, “Think about me for the next few days.” This ideaFever Dreams Pts 1-4 just drops out from somewhere, it might have been walking towards my car, I don’t know. I can’t remember.

I just thought, “Well, okay, I know a good title when I hear one.” I was like, “What’s this Pts 1-4 all about?” It gave me an opportunity to do a little bit of lateral thinking and then I just didn’t want to call it Fever Dreams. I liked this Pts 1-4. It was intriguing to me. I was going, “What can I do with that?” I had never made a record that was in different parts. Then, I got this idea, “Well maybe I can stagger the release and that might be cool for bands.” This is all before the pandemic. “That might be a cool way of doing things. A new way of doing things. I’ve never done that before.” Of course, when the record company heard about this they thought I was a genius, like some marketing genius. It was purely some artistic thing. I just liked the sound of it.

Where do you think that kind of inspiration comes from?

Well, I think you’re picking up ideas all the time. I’ve always kept notebooks from being young. Like a lot of songwriters, and writers, people say things, you mishear things, you write down a load of stuff. These days, obviously, I just put all of this stuff in my phone. I keep going through it and I then decant it, because you go, “No, that’s– No, no. That sounds like something else,” blah, blah, blah. Then you get really attached to things. I trust myself well enough to know when things are strong. Then, I write them on a whiteboard, or whatever. It was only months into the record that I remembered that I used to have a record by the band, The Human League. It was a 45 and it was called “The Dignity of Labour Pts. 1 & 2”. I always liked that. “The Dignity of Labour Pts. 1 & 2”. I think it’s been stuck in my mind since 1980, in the back of my mind. That’s where those things come from. Other ideas you just kind of will them. You absolutely will them. The first song “Spirit Power And Soul”–It was electro-soul.

I thought, “What is that? Electro-soul, someone should do that.” You live with it for a while. I had the tune and I had the melody and I had some of the verses and I had that song for a few weeks. I just stayed on that song. I was like, “I am going to craft this song. I’m going to craft it every day. 10:00 till 6:00, little bits and then I’d drive home and I’d go, “No, that is isn’t right. That’s too melodic,” or, “That’s too this, that, and the other.” It was just real kind of crafting. Then, I went to sleep listening to some audiobook about philosophy, half asleep, 3:30 in the morning I misheard some phrase and I woke up, which I often do and I was like, “Okay, ‘Spirit Power And Soul’.”

Then, I’m so excited. I’m so happy. I’m like, “I cracked it. I’ve cracked it.” This is what I mean, it’s not a chore, but it drives me crazy. Being a songwriter can make you really nuts. Yes, yes, yes, but it’s so much fun when you have those moments when you go, “Okay.” The title “Lightning People”, that was another one that just fell out of the sky and I just kind of went, “There’s a back story there. What is it? Make it into a song. There’s a back story.” It’s great. It’s great.

What would you say to young artists who say, “I want to be a great songwriter like Johnny Marr”?

Inall honesty, I would say that the life of a struggling songwriter who is working on their craft and their passion is better than–I know this is easy for me to say, I get it, but–better to be a starving artist than working in call-center or working in a job where you’re not able to do that because you just gave up. I think it’s really bad for you spiritually, it’s bad for you emotionally. You’re better to just live in your parent’s garage. I really think so.

I’ve got a couple of friends who are great artists and they’re real experts. One’s a sculptor, she’s amazing. Another guy’s a musician. They are absolute experts at what they do. I do believe that people who are great, whether it’s David Hockney or whether it’s Bob Marley, or whether it’s Karen O–whoever, you want a name, a sportsman or whoever–they are students of that thing that they do. No one who is great doesn’t know all the history of whatever it is. Bob Marley knew all about The Drifters. He knew all about Sam Cooke, Kurt Cobain, knew everything about Led Zeppelin. No matter what, he knew all about that flagging. He knew all about the Buzzcocks. He knew about The Smiths. People who do what they do, writers, they know all about–well, they should know about–Joan Didion, they should know about Susan Sontag. If you’ve got that passion for it, that, whether you are successful or not, you can do without any permission, without needing to make money at it, especially with the internet, you can do it. If you take the absolute success…if you take that goal away, the journey of it is really, really fucking rewarding. When you put your head on the pillow at night, if you are great at what you do, doesn’t matter if you’re not Jay-Z. Fuck it. Sure as shit, everybody who’s done really well, they know everything about their craft, is what I’d say.

Leave a comment