To understand the slippery nature of bliss, to glimpse a stress-free manifestation of fleeting euphoria, I would direct your attention to Bill Walton at a Grateful Dead concert. The ancient Buddhists called this state “the divine abode.” Modernity might consider the NBA Hall of Famer as having fallen into the zone – a serotonin-rich wonderland where time is suspended, every shot is all net, and no lifelong synapse destruction can impair one’s flawless recollection of the lyrics to “Scarlet Begonias/Fire on the Mountain.” For three hours, Walton’s fists pump, his head bobbles a groovy “amen,” his smile beams with such incandescent rapture that he might as well be a 7-foot tall, 68-year-old, ginger glow stick. The big man, still throwing it down in this year of the devil’s friend, 2021.

Amidst a depressive cycle of recriminations and outrage, permanent cynicism and Roman cruelty, this is as close as you can get to observing pure joy, apart from maybe watching puppy loops on TikTok or whatever. A psychedelic entrée into ekstasis, by virtue of watching Walton and the skeletons shimmy in the aisles of Los Angeles’ Hollywood Bowl, sold out all three nights of Halloween weekend. Yes, I am aware that The Grateful Dead, the inimitable, cosmically ordained, and tie-dyed jamboree, has ceased to be The Grateful Dead since Jerry Garcia’s final Saturday night in 1995. But that has been beside the point for a very long time.

Over the course of several generations, the songs became mystic canticles, complete with their own affirmations of durability: “No, our love will not fade away;” “I will get by;” “Get back truckin’ on.” These are bumper stickers and favored tattoos, a skull and roses iconography, and a condition of being. These mantras may be recycled, but they acquire a simplistic profundity in the context of broader testament. To the converted, the Grateful Dead have created a natural history of unlikely survival and spontaneous miracles; gunslinger lore, astral journeys, and psychedelic fables – the band beyond description, Jehovah’s favorite choir, the music that never stops – even if the jams of “Drums/Space” could stand for a little more brevity.

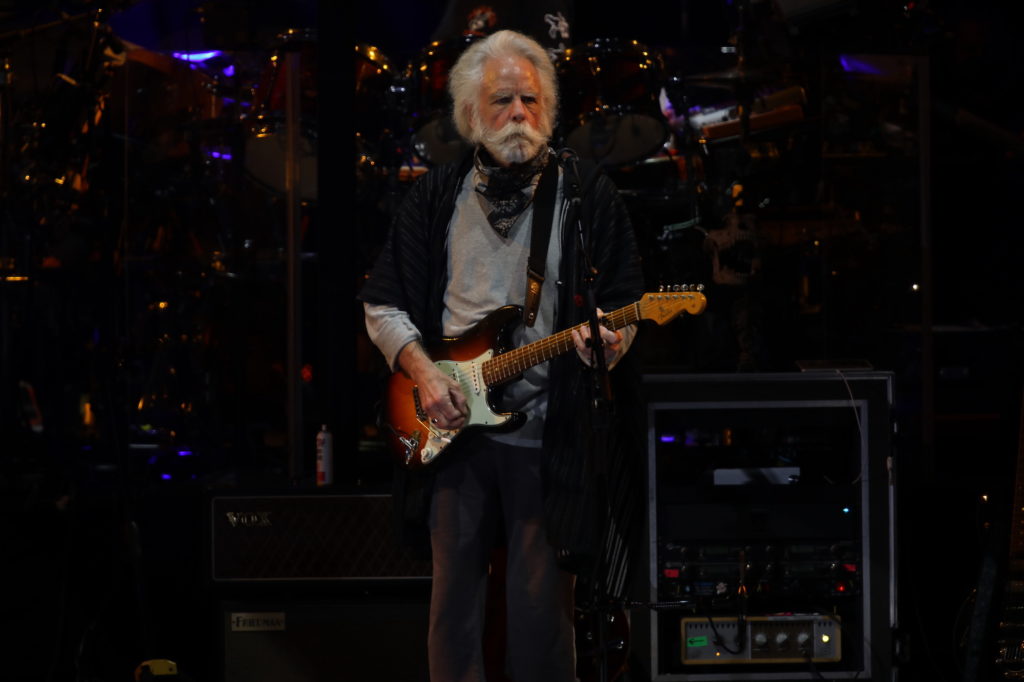

We are now a half-dozen years deep into the Dead & Company epoch of the longest and strangest trip ever recorded. Depending on your vantage point, it’s either a mutation or evolution, but with Bob Weir still handling most of the vocals and rhythm guitar, there remains an oracular presence. A cowboy Moses descending from Mt. Tamalpais declaiming outlaw epics about bloody shootouts in El Paso corrals, estimated prophets on burning shores, and lightning trains that haven’t run since long before half the audience were hatched. He’s joined by the two other remaining stalwarts, drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann (who was replaced by Jay Lane on Sunday after calling in sick), bass maestro, Oteil Burbridge (part of the Allman Brothers resurrection in the first part of the century), and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti (a veteran of various permutations of the surviving Dead members since 2002.) Bassist Phil Lesh remains among the exhaling, but has semi-retired to the Terrapin Crossroads in the sky (Marin County).

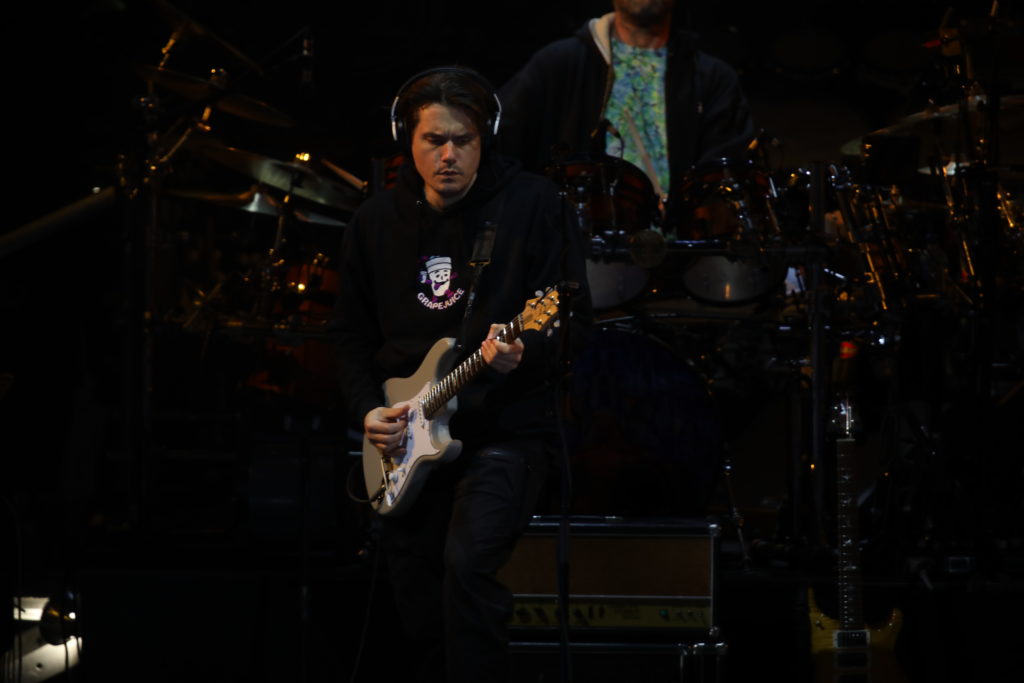

To the right of Weir, inheriting the role of ersatz Jerry, stands John Mayer, bringing a vibrancy and star power that elevate the band beyond the nostalgia circuit into something modern (yet still timeless enough.) By mid-2019, Dead & Company tours had grossed $200 million, a figure now likely approaching another hundred more. It’s a symbiotic pact: Mayer gets enshrined in the posthumous legacy of one of the greatest rock groups of all time, a co-sign and cred boost that allows him to shake off the final vestiges of “Your Body Is a Wonderland” and the lingering phrase, “Sexual Napalm.” In return, he helps make it a multi-generational congregation, a scene extending far beyond what could’ve become a sad scenario of wealthy Boomers and motley burnouts vainly grasping for a vanished heyday. To his lasting credit, Mayer plays with a rich fidelity to the original body of work, but isn’t content merely to imitate Garcia. He gets the tone correct, but infuses the performances with the sensibility of someone who spent their adolescence wanting to be Buddy Guy and B.B. King. He has assumed his ideal final form: Stevie Ray Vaughan for millennials.

But Weir is the nucleus. Weir, who 16 lifetimes ago was a 16-year old from Palo Alto, serendipitously tracing the source of a solitary banjo forlornly strummed on New Year’s Eve, 1963. At Dana Morgan’s Music Store he discovers Jerry Garcia, oblivious to the holiday, waiting for his music students to never arrive. They jam that evening and the Golden Road of the next several decades materializes before them, including a residency at Ken Kesey’s compound with Hunter S. Thompson and Hells Angels, the scourge of addiction, and the untimely death of several keyboardists, the most cursed position in the rock cosmology.

For most of the band’s existence, Weir was the baby-faced, clean-shaven, ladies man, who largely ducked the worst ravages of the road. Now, he is 74-years old, singing western spirituals about “living in a silver mine,” wearing a cotton-white shroud of facial hair, a Stetson, and a bandanna that makes him look like he discovered the Comstock lode in 1859. It’s with him that the faith of the enterprise resides; his integrity unimpeachable, his voice somehow richer for its erosion, the herky-jerky rollicking cadences of his youth substituted for a whiskey and grapeshot timbre. At one point on the third night, the holographic visuals in the background seem to morph Weir into a fluorescent blue and black trail of stardust, tufted by his lion in winter mane, making him seem like the face of God. It’s slightly absurd, maybe, but if we were going to cast that role among anyone still walking the earth, Weir might be the best remaining option.

Reveling in the absurd is part of the beauty of the Dead. This is an outfit depicted by dancing phosphorescent pink and green bears, who may have dosed the entire audience for a Playboy After Dark taping in 1969, and played before the Pyramids of Giza (with Walton there, obviously). They are the physical embodiment of their skeleton jester alter-ego, able to swing between bad tarot ballads of despair and lamentation, and chimerical whimsy. For generations, this hallucinogenic goofiness made them anathema to all but Deadheads. To quote Jerry Garcia “We’re like licorice. Not everybody likes licorice, but the people who like licorice really like licorice.”

Sometime around the end of the ‘00s, a lot of people started singing the praise of Red Vines. Bands like Animal Collective, Darkside, and Real Estate touted and reflected the Dead’s influence. Their best direct progeny, Phish, returned from a hiatus reigniting a jam scene that had grown dormant. Pitchfork, Noisey, and Fader started rehabilitating the band’s once-critically arsenic reputation, which was compounded by a lack of commercial success. The revival dovetailed with the advent of the streaming age, which transformed a hermetic tradition of bootleg live show tapes and Dick’s Picks CDs into something immediately accessible to willing converts. Yet the real turning point came in 2015 with the Fare Thee Well shows at Chicago’s Soldier Field, billed as the last hurrah, but which really operated as a Trojan Horse.

Within a month of that string of shows over Fourth of July weekend, the Dead & Company lineup was announced. They began touring that fall, kickstarting what could well be their sixth renaissance. The owners of Online Ceramics and Liquid Blue can probably already retire off the last half-decade of Dead merch sales. Chinatown Market did a collab that LeBron wore on national television. Drakeo the Ruler wore one too. You can now buy Dead tie-dye shirts at PacSun. Procuring the Dead’s official Nike dunks on the sneaker resale market will cost you almost one month’s rent. Once a punchline ending in patchouli, Dead cover bands like The Grateful Shred and Joe Russo’s Almost Dead can play venues as large as the 4,000-capacity Hollywood Palladium. It’s a phenomenon essentially unprecedented in the history of modern popular music. The Velvet Underground might have a new critically revered doc out, but their most famous cover band starred Macauley Culkin belting out songs about pizza.

There are no illusions that the audience is about to walk into Cornell’s Barton Hall on May 8, 1977; they are here for the total experience, which has somehow endured through all the welter of lost life and wobbly brain cells. For all three nights, the Shakedown Street on Highland Blvd. is a bustling maze of tie-dye shirts and nitrous tanks, jewelry kiosks and hemp hats, semi-pro jam bands doing impromptu sets, and people holding signs begging for tickets. It is a ridiculous, goofy, and inviting party. In the wake of a biblical pandemic and a society hellbent on committing cultural immolation, it is the welcomed evidence of an irregular pulse.

The music could easily be an afterthought to the carnival, but it remains the central obsession. You can rack up cheap jokes about the IG poseurs and the bougie Hollywood Bowl A&R salamanders and the 42-year old goofies wearing silver ball headband antennas, but this is baked into the dosed cake. As with most things worthwhile lately, full appreciation requires a partial suspension of disbelief. On Sunday night, Weir serenaded the crowd with the slow-rolling, love song-turned-murder ballad, “El Paso;” if you closed your eyes, you could almost imagine being in a West Texas cantina in 1893, filled with gorgeous women in frilled dresses and foul omens by the bar. Open them, you could see the video screen cameras panning to Pandora execs in spirit hoodies and aviator sunglasses, and Brentwood commercial real estate brokers dressed like Hugh Hefner. But the point was always been to transcend the cynicism. People have sniped at the influx of lame casuals since “Touch of Grey” brought the beer-drinking, Alpha Tau Omega hordes after it became a surprise MTV hit in 1987.

The point is the moments that miraculously can and still do exist; the ones that exist as a counter-weight to the weirdness of this afterlife reality, the ones that speak to a waning supernatural quality in an algorithmic world. The first night is strong but unspectacular, largely owing to setlist choices. “Deal” bleeds into a moody “All Along the Watchtower;” “Ramble on Rose” becomes a 1:40 a.m., eight shots deep sing-a-long;” The second set builds from a warm-hearted “Sugar Magnolia” into the woozy, mid-‘70s prog suite of “Help on the Way,” “Slipknot!,” “Franklin’s Tower,” and “Estimated Prophet.” On night two, Dead & Co. come out of the intermission with a heat check of “Jack Straw,” Sugaree,” “China Cat Sunflower,” and “I Know You Rider.” The years peel back, the telepathy of the tightly honed, road-tested virtuosos take over; it is obvious even to outsiders what turned this cult into a religion. These are psalms ripe for reinterpretation – whether by another band or within the personal memories long attached to now sacred melodies.

It’s fitting that on the final night, Halloween proper, the Dead came together once more in spellbinding rhythm. The setlist was platonic. “Uncle John’s Band” led into an elegiac “Brown Eyed Woman.” The latter being one of one those Dead songs readily lending itself to multiple visions: a chorus built to be chanted with its brown-eyed woman and bottle of red grenadine. Thunder and rain add elemental tension. The verses run like something out of Steinbeck or Faulkner: a sense that the best days are long gone. They’re juxtaposed with images of violent Depression-era speakeasies, shotgun shacks, illegal whiskey stills and a feeling of lost, irredeemable love. Then there is “Touch of Grey,” written as the band experienced another rebirth but remained plagued by mortal failings and the first degradations of age. In both, there is a sense of triumphalism, an almost Zen acceptance of fate, and a resigned state of grace.

This is the skeleton key to understanding the Dead’s endurance. For the elder generation, those who saw the original iteration in their prime, there is a beauty in simply hanging on and persevering, themes endemic in the songbook from “Box of Rain” to the weekend’s final encore, “Brokedown Palace.” It is a mythic American Torah replete with winners and losers, wronged heroes and sinister villains, those haunted by death but who remain determined to cheat the grave. This is why after too many surgeries to count, Bill Walton remains on his half-metallic feet, beatifically reciting these bittersweet reveries.

For the younger generation, those who showed up just in time for last call, right before they began to take down the decorations and fold up all the chairs, this idea too is contained in the band’s vision. The best songs were nearly all written in the ‘70s and ‘80s, by men born in the ‘40s, old enough to watch the final gasps of frontier vanish, the mystery eliminated by electric media, the pockets of the old weird America snuffed out by the homogenous interstates and big gulp greed. They were the ones along for Neal Cassady’s final tours, who paid him one last requiem, positioned as a bridge between worlds. They were never the actual cowboys or the Appalachian jug bands, but instead, they were other ones who mourned what was disappearing in the rearview. It carries a spiritual resonance for those aware that the soul of what went missing will never return.

So there is Bob Weir, one more time on in the infinite Saturday night. It is actually Sunday, but that’s immaterial. Towards the end of the set, he alights into “Morning Dew,” a primordial hymn about the survivors of the nuclear holocaust, written by a Canadian folk singer around the time of the Cuban missile crisis. Jerry Garcia discovered it via Fred Neil and sang it on the Dead’s first album. Weir was 19. More than a half-century later, in a time completely alien from its origination, but with the same themes omnipresent, Weir takes it over on Halloween night with a weary but invincible bellow. Everything is gone, but it doesn’t matter. His voice cuts through the cold canyon night with clarity. The guitars blink in harmony with the twisting lights of the scalloped stage, and everything moves so slowly that you can almost picture it going on like this forever. For a minute there, this is as close as it gets.

Leave a comment