It’s dead quiet backstage at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, save for the sound of Brandi Carlile’s patent Gucci loafers clicking against the floor on the way into the greenroom. Fresh off a win for Artist of the Year at the Americana Honors and Awards the night before, Carlile is talking fondly about envy.

“Margo Price sang a song last night that made me blind jealous,” Carlile says, sitting on a couch in a rainbow tie-dye cardigan and jeans. It’s the same cardigan she posed in for a photoshoot with the New York Times, because Carlile is not the wear-and-toss type. Growing up in poverty can do that to a person, no matter how many pairs of loafers or cashmere sweaters she can now afford. “I just thought, ‘I fucking love that song, why didn’t I write that?’ So I went right up to her after and told her that God, I was jealous.”

To her surprise, Price, who had just offered a bare and striking performance of her ballad “I’d Die For You,” confessed that she felt the same. “Margo said, ‘Well, you know what I thought the whole time I was writing it?’” Carlile recalls. “’What if Brandi were singing it instead of me?’ And I was like, ‘Really?’ It was just that acknowledgment: it’s a really good feeling.” Carlile pauses for a minute, drawing her sweater close – it wasn’t always this easy to be this vulnerable – before adding, “I fucking love Margo.” They left that night deciding to cover each other’s songs, and she smiles just thinking about it, the same way she does on stage when she hits a note so high the serotonin starts to kick in and she jokingly taps an invisible watch on her wrist.

Carlile’s been doing a lot of that over the past year and change: acknowledging her emotions, her past, her mistakes and her triumphs, and figuring out how to make sense of them all. It rolled in heavy waves during a careful excavation that came with the writing of her memoir, Broken Horses, and a life forced to a halt thanks to the pandemic. She’d been running – galloping at full speed, really – since the 2018 release of By the Way, I Forgive You, which won three Grammy awards and turned her from cult hero into a household name. Her new album, In These Silent Days, is a result of all that digging. Digging up of influences (and now friends) like Joni Mitchell and Elton John but also the grunge sounds that surrounded her growing up in Seattle, a digging up of emotions and love and brutal truths and letting the soil run through her fingers, searching for what lingers. A digging up of the disappointments she’d felt while dancing the realm of country music, her childhood love, or the thrill and drama of rock and roll. And a burial, when it needed to be.

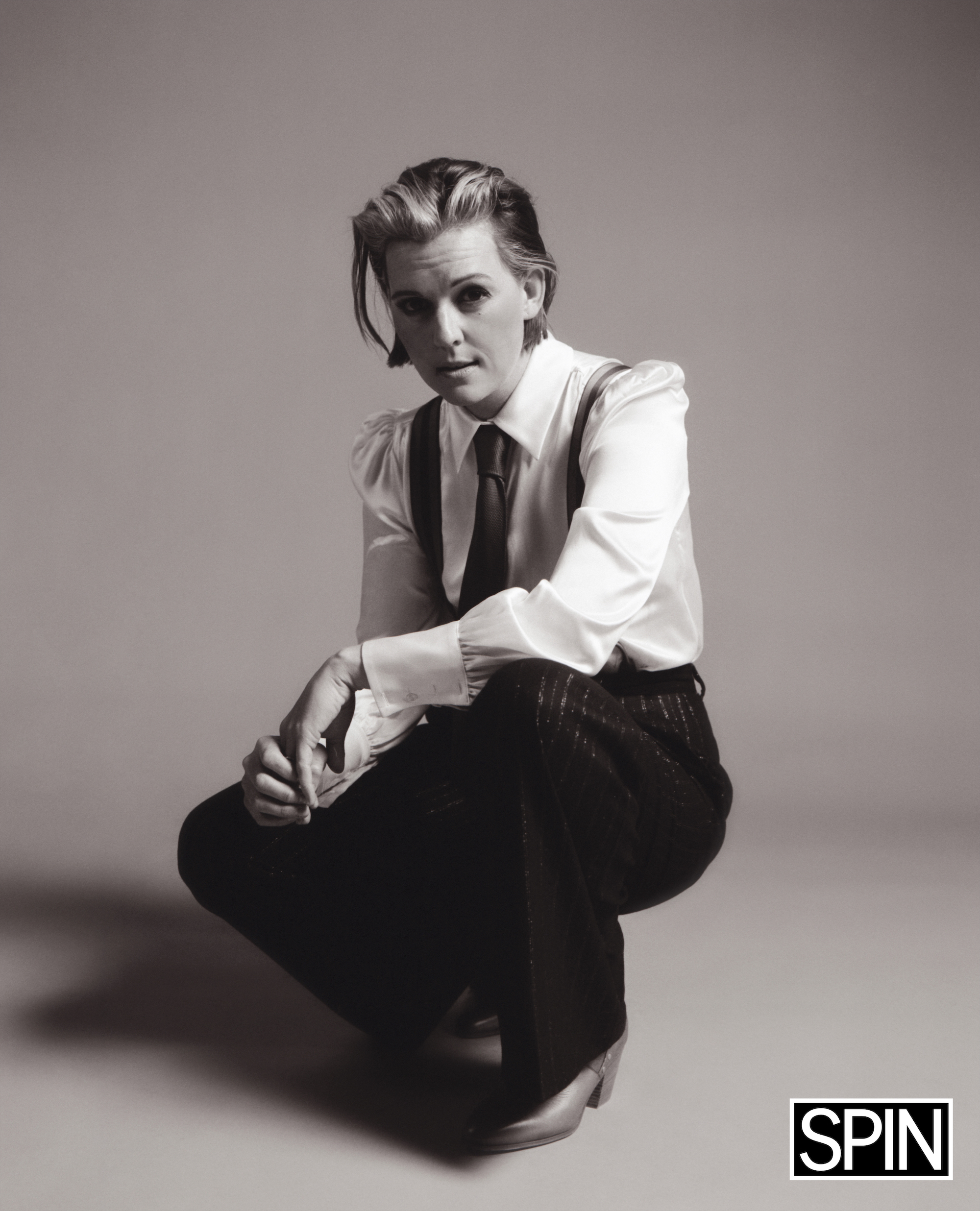

There’s a part in a chapter of Broken Horses where Carlile talks about figuring out her look for a new album and then making the “content pieces” that go along with it, those nagging promo photos or bits for social media that swirl along in the marketing machine. This time, there are suspenders and ties and ascots and even stronger brows and imperfect chunks of blonde in her hair – she looks authoritative and aspirational, just the right amount of untouchable star. Carlile’s always juggled, especially of late, being both otherworldly and of the people: she loves the drama and the bombast, and she learned to sing those big notes by belting Freddie Mercury alone in the car or entering singing contests as a young kid. But there was also a point in recording In These Silent Days where she, Phil and Tim Hanseroth (a.k.a The Twins) and producers Dave Cobb and Shooter Jennings started to wonder if the mystery around celebrity was gone – that the pandemic, with our ability to see the bare faces and frayed carpets of our favorite stars, had leveled the playing field.

“It was like, ‘look, they have the same Urban Outfitters rug that I have, that I got for 40 bucks’” Carlile says, laughing. She unwraps a cough drop (“Not COVID!” she assures) and places it in her mouth, those blonde streaks popping in the fluorescent backstage lights. “We realized, dude, we are pretty much the same. And I kind of say good riddance,” she adds. In its quietest moments, In These Silent Days ended up showing that you don’t have to lose your humanity to be larger than life. “I don’t want to go back. Not like it was before.”

Nashville had become a second home for Carlile by March 2020, and when a tornado hit the place at the beginning of that month, she knew she had to be there — specifically at a benefit concert called “To Nashville, With Love.” It was a massive lineup featuring Jason Isbell, Sheryl Crow, Dan Auerbach, Yola and Price amongst the performers, and Carlile played her song “The Joke” as a much-needed shot of resilience. But as the news of COVID started to turn from distant fears to a hovering ghost nearly that morning, things felt tense. Elbows were bumped instead of hugs. Bottles of hand sanitizer appeared backstage. Even the bathroom attendant was making sure guests washed their hands for a good 20 seconds by asking them to sing a verse of Lizzo while they scrubbed. In her heart, Carlile knew everything was about to change, and by the next day, it had.

She and the Twins flew back to Seattle, where they live on a sprawling compound about 40 minutes outside of town. Suddenly they were confronted by aching, haunting quiet when the world slipped from constant noise to silent days. Her book, nearly completed, sat unfinished without a final chapter. She thought it would end on a high note, but what do you even say when a life defined by movement screeches to a halt?

“I was like, ‘Okay, I’ve got a responsibility,’” Carlile says. “I’ve got to keep everybody out of trouble, emotionally. I’ve got to keep people out of depression. I’ve got to keep the band and crew paid, and we have to find a way to adapt to the situation. We’re going to get cameras, we’re going to learn to film each other. We’re going to make sauce. We’re going to build a deck. Everybody’s going to be kept busy. No one’s getting bored.”

Carlile isn’t good at boredom. She’d been touring nonstop since her debut self-titled LP was released in 2005 and had no intention of slowing down. But the sudden stillness gave her permission to finally spend an extended amount of time at her log cabin with her wife, Catherine, and daughters, Evangeline and Elijah — and to get her hands dirty. She built a deck (and is damn proud of it), tended to her garden, and even got her boating license to spend more time on the water. She and the Twins even stopped drinking regular coffee (decaf for Phil and Tim while Carlile replaced hers with Willie Nelson’s CBD-enhanced line, “So we could be kind of stoned at the same time”), and they all met in the woods for cocktails while they alternated cooking.

“I guess it’s a little bit frantic,” she says. “But we had to do something, because we’ve been waking up to day sheets for 20 years.” She finally finished the ending to Broken Horses as the world shattered around her, and she realized she didn’t need to conclude on a note of victory, but of perseverance.

While writing her memoir, she had to confront choices she’d made in the past — particularly the choices that’d made her angry. The things she’d let slip. The times she’d shrugged off questions about being a woman or queer and pretended that she didn’t have to scale walls she knew existed. “Especially catering to other people, catering to bigotry, laughing at jokes that aren’t funny, putting yourself on the outside,” she says. “You know, settling for a seat at the adjacent lunch table. I just thought, ‘Fuck! That’s not right.’”

And that anger changed something inside of her.

On her previous records, songs were always written almost as premonitions. She wouldn’t know what she was singing about until months later, tapping into the emotions embedded in a song like an act of Freudian therapy on herself. Despite the intimate nature of her songwriting, she’d never really been much for talking about her feelings out loud. But on In These Silent Days, she started writing from specific intention. She knew what she was thinking while she was writing it, or sometimes even before. “I just had so much more truth to pull into the record,” she says.

“There’s so much that takes you left or right of what you’d expect in Brandi’s current writing, and I’m so glad to be witnessing this kind of growth from a woman we’d all be forgiven for thinking was already fully actualized,” Yola says. “The path for Brandi is unset and free, and that is why she is forever a musical threat and a master.”

The day she finished Broken Horses, she walked to the piano in her home and the first song came out. “Throwing Good After Bad” may be a solemn piano ballad that ends the album, but it began the journey. “Broken Horses” was next, all fire and fury with a scream that serves as a universal stand-in for a quarantine — or a lifetime’s — worth of pain.

The Twins’ strong roots in the Seattle rock scene (getting their start in a band called the Fighting Machinists) fuse seamlessly with Carlile’s balance of twang and propulsive love for a big, anthemic moment. She’s probably one of the only people outside of Robert Plant who can get away with singing Led Zeppelin songs live, and she shared the stage with Pearl Jam just last week, dueting with Eddie Vedder on “Better Man.” After covering Mitchell’s Blue and spending a good amount of time with Elton John, she’s at the point where she can now call her childhood heroes friends. On the new album, she offers a way to absorb — not just pay tribute to — those people who fill our silence. We’re all a sum of our parts anyhow, and that’s something to run to, not hide from.

She ran to Mitchell on the album’s second track, “You and Me on the Rock,” — a tale of love and faith written for her wife through a very Mitchell-evocative melody hammered out on a dulcimer. The band Lucius (whose album Carlile just produced) provides some gorgeous harmonies “Brandi sent over ‘You and Me On The Rock’ with full confidence in us to bring what it is that we do to what was already magical,” says Lucius’ Holly Laessig.

Adds her bandmate Jess Wolfe, “That’s her: inclusive, uplifting and supportive. She is a force and we consider ourselves very lucky to call her a friend and collaborator.”

Carlile says the pandemic was “really a make or break period in people’s lives,” and she saw some bitter divorces and heartbreaks play out when the fancy clothes were traded in for all-day pajamas. “I just realized that when I stopped making money and being ‘Brandi Carlile’ and everything that made me cool, and Catherine still loved me, and I still loved listening to her talk, that I had built my house on a rock. We all want to know we’ve built our house on a rock in one way or another.”

In many ways, her song “The Joke” became that rock over the past few years. It was the last piece of By The Way, I Forgive You and the moment that opened her up to the world on the Grammy stage. “It was a once in a lifetime song,” she says. “And I didn’t want anyone else to worry about me feeling the pressure. But I wanted to hit that mark of drama again.” When she wrote “Right on Time,” she “felt like the pressure was off in terms of getting my heart to come out of my mouth.” It’s high-drama with huge notes like a fever dream, and it’s supposed to feel big. It’s supposed to shake you, because we’ve all gone a little bit frozen.

Carlile and the Twins spent much of quarantine playing routine campfire shows on their property – Indigo Girls covers, requests taken online, and more – but she knew she had to get to the studio before the new songs became stale or she busted one out in the middle of an Instagram Live. They initially canceled a trip to Nashville as COVID numbers never seemed to wane while the town continued in an eternal party, but with some strict podding and new COVID guidelines at Cobb’s RCA Studio A, they finally buckled down and made the trip last fall.

No one was allowed in the tight quarters of the control room, so they set up in the middle of the expansive space together. They sang, ate lunch, recorded, wrote, cried and laughed all in the same spot. “It was kind of old school, like a lair up in Woodstock or something,” Carlile says. “I always wanted to be in the same room with the engineer, but it’s crazy for the vocal bleed because it’s in everything, and it turns out I’m very loud.”

Carlile would come in early to get a tired sound when she needed to sound tired, but she also let herself go as big as she wanted with sky-reaching notes and vocal swagger. She could be relatable but also superhuman, the kind of musical magic she studied as a kid.

“With this album in particular, I’m happy to see the superstar side of Brandi flourish,” Shooter Jennings says. “She’s always been such a down-to-earth entity, but there is an otherworldly side to her that comes out on stage. It’s like seeing an artist of the universal magnitude of an early David Bowie in the raw chemical form. I’m excited that she’s letting go and letting her inner Prometheus come out and set the world on fire. She’s got a bleeding edge and a world-class voice.”

Sometimes, Carlile has to be careful. She’s been known to blow her voice out at soundcheck by singing in full force to a crowd of five. “I am a total ego vocalist,” she says matter-of-factly before letting out a big chuckle. “Like, I have problems with it, because I was raised in fucking karaoke contests singing against little girls doing Whitney Houston and stuff. I am the whole ‘Who can hold the note the longest? Stay up to watch the Grammys to see if Celine Dion can really do it’ kind of person.” She loves sending clips of “absurd” vocal moments to her friends, like R&B singer Monica. Right now, they are both extremely obsessed with Yebba (“Cannot think of anything else,” Carlile says).

Monica joined her on stage at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium for a quarantine show, and now Carlile is going to produce the album that she’s in the writing stages of. “She’s a really spectacular person, and a brilliant singer,” Carlile says, her eyebrows raising with excitement. “And she’s going to have a really beautiful roots record. She’s calling it country, but I don’t know. You know how I feel about the ‘C’ word.”

Carlile has complex feelings about country music these days. It’s the genre she’s loved ever since her childhood, singing Tanya Tucker’s “Delta Dawn” and fighting for the “western” in “Country & Western” in her small Washington town. It’s where she got to come back to full-force when singing on stage with Dolly Parton and her supergroup The Highwomen with Amanda Shires, Maren Morris and Natalie Hemby. It’s given her dreamy moments like producing Tucker’s comeback LP, While I’m Livin’, or even popping into the mainstream on a Dierks Bentley song. She’s helped enrich the genre and push it towards a different future, but the genre hasn’t always been so kind in return. Being a country artist (and even a country fan) is an incredibly complex thing in a time where straight white men still dominate almost every radio chart. It’s a constant push of people grasping at everything they can to keep it securely in the past on the basis of “nostalgia,” and others who just want it to crack wide open.

Here at the Country Music Hall of Fame — a museum filled with relics and treasures of the genre’s history — Carlile’s suit from her Highwomen performances sits behind glass. But at the same time, the CMA Awards entirely shut out the band from nominations in 2020, and their singles “Redesigning Women” and “Crowded Table” barely made a dent on country radio despite a promo push. She sees the cracks differently now and how to rip them open for more women and queer people, Black, and other underrepresented voices everywhere — and she also sees the places trying so hard not to change that it’s almost impossible to get a foothold. Add constantly rising fame to the mix, and it’s enough to give her pause.

“Becoming a household name has been complicated,” she says, quieting a little. “Because you don’t get to choose the people you become a household name for.”

It was a few weeks ago at BottleRock Festival in Napa Valley that Carlile was trying to top herself. “I was just out there doing everything I could, ‘Rocket Man,’ ‘The Story,’ ‘The Joke,’” she laughs. “Jumping off of amplifiers and shit, you know? I felt like it was going alright. But it was nothing compared to what The Highwomen did by just standing there in line and singing ‘Crowded Table.’”

Shires, who founded the Highwomen, had been unable to make the show due to a recent health scare, but saw the moment as a way to fulfill the mission that she’d always planned for the band. It could be a rotating cast of women and non-binary folks from all walks of life — anyone who had been pushed out or unheard. Brittney Spencer, who got Shires’ attention one day in 2020 by posting a cover of “Crowded Table” on Twitter, got the call to complete the quartet. She learned the songs by pulling an all-nighter and hopped on a plane from Nashville to make it to the show on time.

“Brandi’s level of musicality makes you want to bring your A-game whenever you’re in her presence,” Spencer says. “And her generosity is the kind that spikes other people’s capacity and desire to give. She has an understated magical ability that compels others to show up as their best, most authentic and innovative self.”

Carlile’s come to have a reputation for compiling an island of misfits she can help boost up and show to the world, as well as her philanthropic work with her Looking Out Foundation. She’s not precious about holding her voice back as some sort of rare treat. She sings on her friend’s tracks (like the newest from Lucie Silvas) and has been bringing dynamite guitarist Celisse Henderson to shows, including a recent performance at Red Rocks. She’s steadfast and serious when it comes to being a visible queer family, and relished the chance to be on the cover of Parents magazine with her wife and kids. An outlet like that isn’t always the first stop for rock stars in their prime, but Carlile thought it was important because it’s the kind of thing someone in a small town picks up in a doctor’s waiting room and finally sees themself.

“It’s a little bit of a risk, because I don’t want anybody to be too fascinated with my kids or the things that make us normal,” she says. “But at the same time, I just so wish I’d had something like that. I wish there had been some other movies or books or songs about queer families that I could have turned to and gone, ‘Okay, there’s a template.’”

It’s hard to be a template, though. It’s not uncommon to see references to her that veer on sainthood, which both excites and terrifies her. “It’s really scary, because I’m so flawed,” Carlile says. “But I have all the same poor kid afflictions that anybody else does when they get a little bit of money or power. I’m bad with money. I make selfish decisions. I veer in and out of fucking messianic complexes and narcissistic behavior, so it would be easy to catch me up. But at some point, you have to accept and know that people are going to choose their own leaders, and I’m just going to continue to be myself. We can’t let it dampen our activism. We just have to keep powering forward, because we can’t do nothing.”

That doesn’t mean there aren’t times when she thinks about what it could look like on the other side, where decks can be built any day and there’s always gardens to tend to. “A really big part of me wants to ‘Make a lot of money and quit this crazy scene,’” she says, singing that last bit of Mitchell’s “River.”

She sang the same words to Sturgill Simpson earlier in the day on a phone call, talking to him after they both took home Americana Awards, his for Album of the Year. An hour or so later, she’s telling an audience at a conversation moderated by journalist Ann Powers that it’s a bit of a dream to do a country duets record with someone like Simpson, Tammy Wynette and George Jones style. At that moment, Carlile looks out into the crowd, scanning for someone. The decks can wait.

“What do you think, Shooter? Will you produce it?”

Leave a comment