This article originally appeared in the December 1989 issue of SPIN.

Ian Stewart, 1975: The Beatles… I think they are nice lads who wrote pretty songs, but they are horribly overrated. In fact, most of the Liverpool groups were overrated, they were all musically inept completely. Some of them could sing, but they could never play their instruments. You could count the number of good musicians who came out of Liverpool on one hand.

By 1964, the Stones took off, and it was obvious that they were going to have the same kind of following that the Beatles had got. But Andrew [Loog Oldham, the Beatles’ publicist and the Rolling Stones’ first manager] thought they couldn’t go on playing Muddy Waters material and maintain it, so he had to alter the repertoire and the approach and everything of the group. He was really more interested in what they looked like… you could call him musically barren, really. If you look at early pictures of the group there are those five longhaired little horrors, and Muggins here. So I was pushed out.

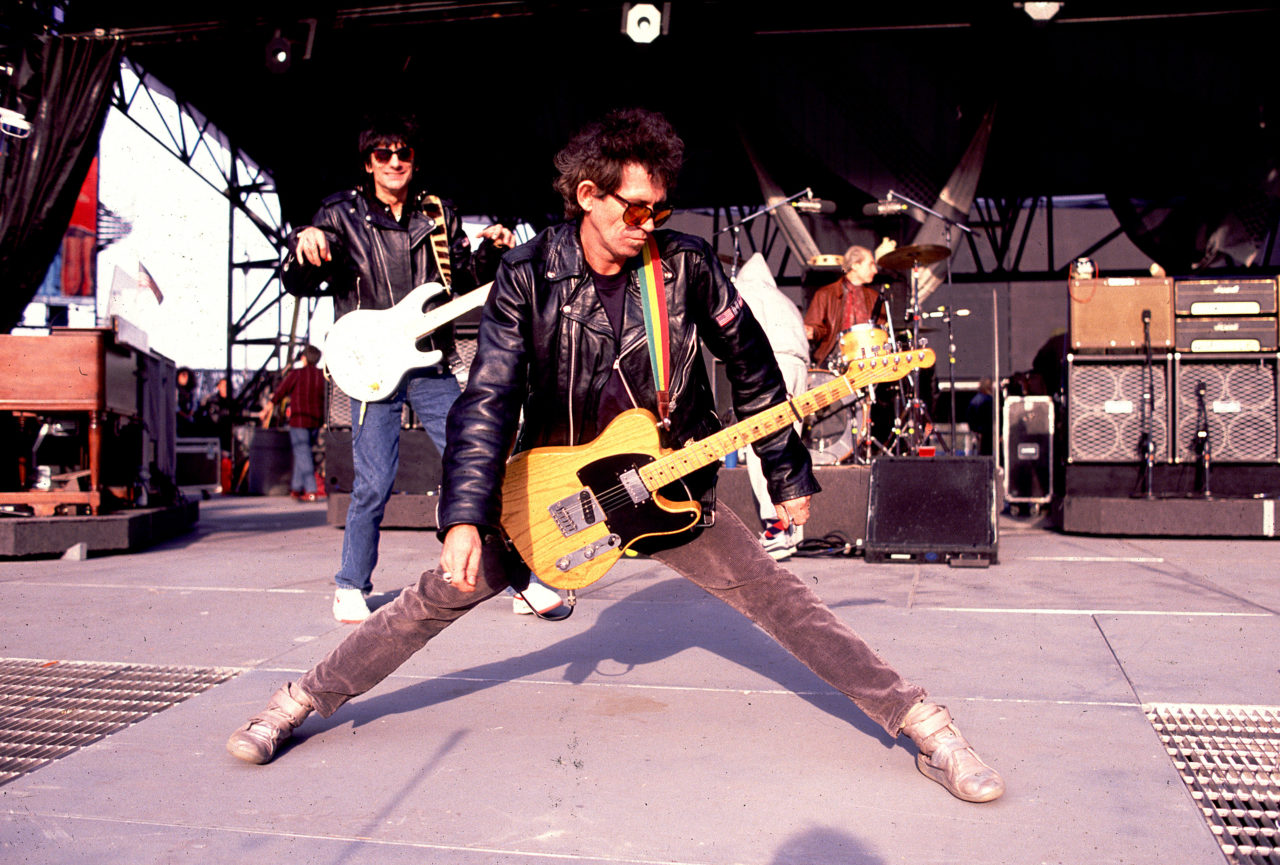

Keith Richards, 1989: We knew that all we wanted to do was play guitars; you want to play the blues, man, and you know, we are the men with the mission. So there you go, out on the ballroom rock’n’roll circuit, and we just tried to figure a new way to play together and turn people on to Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and Chuck Berry via us. Like, “If you’re interested in this, then you should hear the real stuff.” That was our only criteria, not the money.

Being popstars didn’t even come into the realm of possibility. We saw no connection between us and the Beatles; we were playing blues, they were writing pop songs dressed in suits. I mean they were an encouraging sign of a new trend in popular music, but to be in the charts, or to be popstars—we were almost a reaction against all of that. We were too hip to be popstars, it was like that was the only dignity we had left.

The first time I met Mick Jagger was at an Eric Clapton concert in 1974. He sidled over and made fun of something I’d written about Jimmy Page’s clothes. I looked at Mick, couldn’t believe the sequin-covered Capezio dance shoes he was wearing, and told him so. We’ve been sparring ever since.

In 1975, Mick asked me along on the Stones’ Tour of the Americas, in some trumped-up position we called “rock’n’roll press liaison,” and I was only too happy to join the circus for the summer. Over the past 14 years, I’ve been around the Stones a lot; during the 1978 and 1981 tours, for Mick’s two solo albums, and Keith’s solo album and tour last year, at birthday parties, Christmas parties and baby showers (a specialty of Jerry Hall’s). I still remain a fan.

It is impossible to cover the Rolling Stones on the Steel Wheels tour without acutely feeling the loss of Ian Stewart, the man who started the band with Brian Jones in 1961, who acted as their road manager and played piano on their albums and onstage, and who died of a heart attack in December 1985. I was fortunate to be the only journalist that Stu trusted enough to talk with on the record, and his comments about the band he loved are as pertinent today as they ever were. The current Stones tour is dedicated to Stu; he always was the glue that held it together.

Washington, Connecticut, July 26, 1989. Mick Jagger’s 46th birthday party at the Mayflower Inn: Barbecued chicken, corn on the cob, potato salad, a huge cake, all served outside under a large tent. Mick is wearing a white shirt, red brocade vest and blue jeans. Keith wears a billowing black coat. Bill, Charlie and Ronnie play pool. The Wood children—some are Jo and Ronnie’s together, one is his and one is hers, from former marriages—are gorgeous. So are Keith and Patti’s blondes. So many children, so many blondes. A real family affair. Author Fran Lebowitz sits at Mick’s right, Jerry Hall—in a floral print dress, Chanel handbag and high heels—is at his left. The new Steel Wheels album is piped in over the outdoor speakers. Happy Birthday Mick.

New Haven, Connecticut, August 12: “No one works a small room better than Jagger,” Keith said to me last year, and so, when I heard that the Stones were planning a secret, surprise set at Toad’s Place, I canceled my plans to see Danzig at the Ritz. When the Rolling Stones beckon, you don’t say no. To this day, I remember the show that they did at Toronto’s 400-seat El Mocambo Club in 1977 as the best Stones show I’d ever seen, and I wanted to see them up close like that again.

Upstairs in the VIP balcony at Toad’s were Keith Richards’s wife Patti Hansen, his father Burt, CBS Records President Tommy Mottola, Daryl Hall, Joey Ramone and staffers and friends of the Stones. But downstairs, the floor was packed with those who had come for the regular Saturday night dance night and got the surprise of their lives.

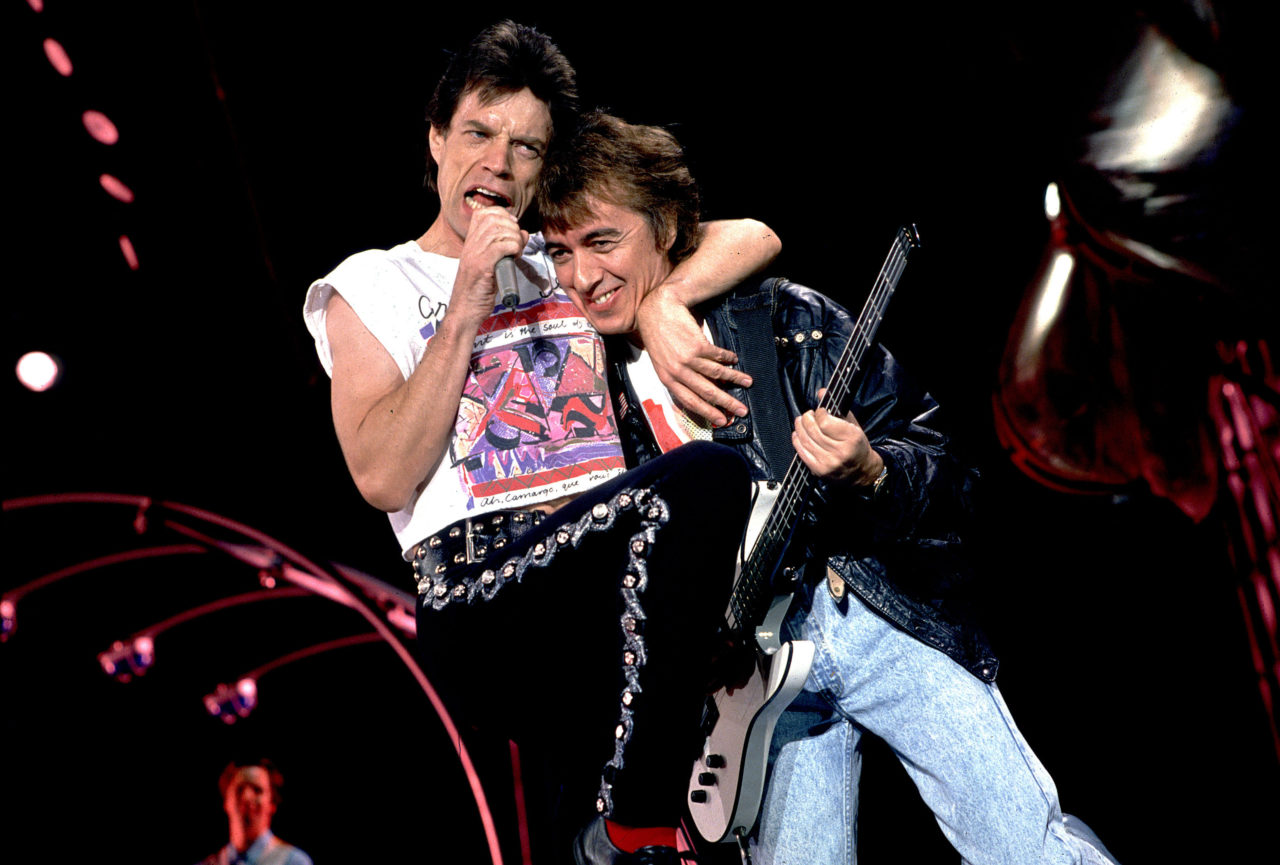

The Stones ambled onto the stage at 10:30 p.m., and without any fanfare, broke into “Start Me Up.” What followed were nine Stones classics (including “Honky Tonk Women,” “Brown Sugar,” “Miss You” and “Tumbling Dice”), two new ones (“Mixed Emotions,” “Sad Sad Sad”) and the excitement of seeing a legendary band at the height of their power, turned on to be playing live to the public for the first time in six years. (In February 1986, the Stones did a live blues set for invited guests at London’s 100 Club as a tribute to Ian Stewart, but the last official show was in 1982.)

Most impressive was to see Mick and Keith together onstage again, playing the extraordinary music that they have contributed to the culture. With a passion and energy that performers half his age should envy, Jagger led the Stones through a 45-minute set that had even the most jaded survivors (I’d seen nearly 65 Stones shows) excited about the coming tour.

“Best show I ever saw,” enthused Tony Mottola after Toad’s. Would there be another club date soon? “One’s quite enough, dear,” said press liaison Tony King. “Let’s not gild the lily.”

Ian Stewart, 1975: I think that you’ve got to admire Mick for sure, because of what he takes on, in that every other band will just go onstage and be done with it. Mick is totally involved with every aspect. Most groups get onstage and play, and everything else is left to managers, record producers, accountants and other staff members. Mick literally supervises everything, he has most of the original ideas and he usually wins his arguments with advisers who tell him what he can and can’t do. He takes on nearly all the responsibilities for the Rolling Stones, and I mean obviously he’s got his legal people and his financial people, but Mick is always on top of everything, more or less on behalf of the other three. Yet, he could trot away and probably make a lot more money doing movies, he could do a single album or tour if he wanted to. I sometimes wonder why he takes all the responsibility for the Rolling Stones. I mean I know he loves doing it, but it means really that he has to work 365 days a year.

Garden City, Long Island, August 1989.

SPIN: Why did you want to do this Stones tour?

Mick Jagger: I loved playing my solo gigs last year; if I hadn’t enjoyed that, I wouldn’t have done this. I probably wouldn’t have been so confident doing this, either. But I get a lot of buzz out of doing other things—I get really involved in what I call business. I just love all the graphics and the stage design and all that. If it wasn’t for that, it would be really quite boring, because you’re doing the same songs. I mean I can do ‘Jumpin Jack Flash’ in the bath at midnight, on my head. I don’t need to rehearse to do that, I really don’t. But to make it different, from the stage to the T-shirts, it’s a tremendous amount of work, but it’s also fun because it’s not something you do every day. To me, that keeps the interest going, as well as the music. The music’s great and all that, but it isn’t 100 percent of the show. It might be for Keith, but it really isn’t. It’s a huge show and it’s got lighting plots and gimmicks. It’s like going to see a musical—you want hit songs but that isn’t going to be enough.”

Can’t anyone else do all that?

Mick: No, no one would do it and it would come out wrong and everyone would moan. Charlie’s been really helpful, actually. When we were doing Dirty Work I didn’t have anyone helping me and it was hopeless, but now Charlie’s been a great help with all the visuals and everything, so that’s always good. But I am very focused on it. I mean you should only worry about what you do, but I have to worry about what everyone else does because if I don’t, it might not come out like I want it to.

The Garden City Hotel is a luxurious hotel set in what appears to be a prosperous area. It’s two minutes away from a Bloomingdale’s (where Patti Hansen has been shopping) and 10 minutes away from the Nassau Coliseum where the Stones are in rehearsals (the massive stage has to be set up sideways in the arena). The hotel is now home for the band and the entourage for two weeks. Logistics director Alan Dunn (who joined the Stones in 1967 and laughingly refers to himself as “the longest-serving employee”), talks on the phone; his usual array of maps, lists, itineraries and transport plans are neatly organized in front of him on a desk. He points out his space-saver hangers—the kind you can order on TV—and everyone immediately decides they want some; security man J.C., Ron Wood and this reporter. Woody mentions that Mick’s got him up running now during the day; “Yeah,” someone laughs, “running to the bar.”

SPIN: There always was the attitude that you and Keith were on a different timetable than the others.

Ron Wood: We used to be. We used to operate like that; rehearse in the studio, forever being in there, running over, working out songs. I suppose we’d get boring for Bill—he’d have to cancel dinner date upon dinner date. Cancel his visits to clubs in London and Paris and stuff. I think Bill had lost hope that we could do an album in a reasonable amount of time, but I didn’t.

Financially, were you relieved that the Stones were working again?

Ron: Financially, it is a relief. because let’s face it, I have a big family to support. But the biggest relief is that the institution of the Stones is still going. It would have been devastating to see that crumble through hearsay and stuff, because I knew that underneath, everyone was friends.

At 42, you’re the youngest member of the Stones.

Ron: Always will be.

Keith Richards: What a trauma it’s been for the group that Ian Stewart has taken the dive on us. We’re just now coming to terms with it, it’s taken us over three years to be able to face the fact that the old bugger ain’t gonna walk in the door anymore. It’s difficult to explain because in the great, big world out there nobody was interested in Stu, but to the band he was incredibly important, which is why he was always with us. And it’s not until he was gone that you really realize quite how important he was to the band.

SPIN: When Andrew Oldham “pushed him out,” as Stu described it, why didn’t he leave? Why did he stay on to be the road manager and piano player?

Keith: I don’t know. Maybe he saw more in us than we were capable of understanding. Maybe he had a big heart anyway, which was obvious, but he really was the conscience of the Stones. He was an anchor for us, something to hang onto. He was there first, and it really was Stu’s band, you know. He probably just figured O.K., I don’t care, I understand, and also, he didn’t want to be a popstar—probably no more than Charlie Watts ever wanted to be. He’s actually embarrassed, you know. It’s totally unhip to be a popstar.

How do you feel about being a popstar?

Keith: I’ve learned to live with it. I mean I’ve got my feet in both camps on that one. I understand having an ego and wanting to show off enough like I do. I mean, I know a million great musicians who just freeze on the stage: they just can’t face people. But you get them in the back room and they’ll play your ass off. The formula is sometimes impossible to put together.

But Stu wouldn’t have been comfortable as a popstar, so he became our roadie and when you’re making records your roadie becomes one of the most important people. For whatever it’s worth, it should have gone on longer, but Stu had a great life and it was perfectly compatible with the kind of personality he was. He was there on the records and if he felt like it he’d walk onstage and play, the piano was there for him. Sometimes he’d have Golfing Monthly on the music stand on the piano, but he was always the perfect counter for all the bullshit we had to go through. He was always our central point, he was the glue for all that madness. And now he ain’t around, but you’re still sort of waiting for him, with that back pocket bulging with the wallet and the screwdriver, and the moccasins.

Flashback, 1975 Tour of the Americas: In New York City, discussing what kind of a show to do, Jagger says, “Those kids are all on downs, aren’t they? They take quaaludes, more downs, and smoke pot and then take some heroin and cocaine and then Ripple wine, right? Maybe we should all get together and take all that stuff, and see what would entertain us.” In Kansas City, the Eagles and Joe Walsh hang out all night with Keith and Ronnie. Chess Records heir Marshall Chess is practically onstage at the Boston Gardens during the show, halfway between an amp and the drums, in the spotlight. In Memphis, excitable tour manager Peter Rudge wants to use real live elephants as security. On July 4, in Fordyce, Arkansas, Keith and Ronnie are detained by the law and charged with reckless driving and possession of a weapon (a knife). In Los Angeles, actress Lorna Luft follows Bianca Jagger around for days like a puppy dog, and Mick tosses a bucket of water on her sister, Liza Minelli, as she watches the show from the front row of the Forum. Everyone goes en masse to the Roxy to see Bob Marley’s show, sits in the balcony, and drinks margaritas. In Buffalo, Mick, Keith, Woody and Billy Preston stay up all night and listen to Rod Stewart’s new album, make tapes for each other, order a ton of room service, and shriek with laughter at an appearance by Frankie Valli on a local morning TV talk show. The plane ride from Buffalo to New York is enhanced by a major food fight; no one escapes unscathed. In Toronto, when his own undergarments disappear, Mick Jagger borrows this reporter’s white lace bikini underpants to wear under his diaphanous trousers onstage at the Maple Leaf Gardens. (Two years later, in Toronto, Keith is busted at the Harbour Castle Hilton by police looking for his girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg, and Margaret Trudeau, the wife of Canada’s Prime Minister, is seen wearing a white terrycloth bathrobe on the same floor of the hotel that houses the band. A scandal erupts when Ms. Trudeau follows the band back to New York City.)

Opening night, Philadelphia, Sept 1, 1989: Tour promoter Michael Cohl, head of Concert Productions International and the Brockum Group—who oversee the tour and the substantial merchandise—looks around the dressing room lounge and observes, “The band is very focused on what they want, how they want it, and one of those objectives is atmosphere. There are kids and wives around, it’s a family-oriented atmosphere now.”

Jerry Hall wears a bright yellow, skintight minidress, and introduces her daughter Elizabeth, 5, whose mouth is smeared with red lipstick, to friends. Keith and Patti’s daughters Alexandra and Theodora run around while Mick’s teenage daughters Jade and Karis sit and gossip on a couch. Keith and Woody play pool with longtime Stones horn player Bobby Keys, who asks, “Like this suit?” (A gray silk item.) “I got it right next door to the Apollo Theater on 125th Street.” Keith’s mother is there, so is his son Marlon and daughter Angela (their mother, Anita Pallenberg, will arrive the next day), and Jo Wood’s got her brood in tow. Patti Hansen sits and talks to Charlie’s wife Shirley, and Patti LaBelle—who has sent over a catered soul food feast—introduces her son Zuri to the assembled. It’s not exactly the Grateful Dead—there are too many Chanel handbags around for that—but it’s family indeed.

“I quite like them there,” Mick would say later on. “I think it provides a lot of support. Some people might feel it’s a nuisance, but you’ve got to put it in perspective. They’re all so experienced that I don’t think it’s a problem. Actually, they were all very supportive, I think. And I was less nervous this opening night than any opening night I’ve ever had. Even with Keith’s mum there. I mean I’ve known Keith’s mum since I was 4. It’s almost like having me own mum there.”

Ian Stewart, 1975: They are getting to be sort of part of showbiz now which I don’t think was ever the idea in the first place, but this is the way Mick wants it, he wants to have a theater production. I mean I suppose it’s funny in a way and they spent a million dollars and the stage opens up and the kids loved it and the Stones were on it and then it closed again and it is the best rock’n’roll prop, but so what. I’m not knocking it and I’m certainly not knocking the skill and application of the crew that made it possible. But if I went to a Stones concert or a Count Basie concert I would want to enjoy the Stones or the Basie band without distraction. And I’d be knocked out by Keith Richards or Al Grey as the case may be, and if the stage went up and down at the corners, well, that would be interesting at best but a distraction at worst. I just wonder if it’s really worth it. Mick believes that people want to see a total production and maybe they do and I am probably completely in the minority.

The Show, 1989: It’s a total production. The stage, designed by Mark Fisher, Jonathan Park, Mick Jagger, Charlie Watts and Michael Aherne, with lighting design by Patrick Woodroffe, looks like an abandoned factory, or a futuristic grain processor, or a small city, depending on your point of view. Adorned with flashpots, fireworks, video screens, inflatable dolls a la the Macy’s Parade, it presents two and a half hours of nonstop Stones history. With the addition of backup singers Bernard Fowler, Lisa Fischer and Cindy Mizelle, horn players Arno Hecht, Crispin Cioe, Hollywood Paul Litteral and Robert Funk, and keyboardists Chuck Leavell and Matt Clifford, there are more people onstage than ever before for a Stones show. Still, the focus is on the band as Mick runs along the platforms, up the stairs, and takes the elevator 75 feet up in the air to the very top of this edifice for “Sympathy for the Devil,” where, in a dramatic spotlight, he casts a shadow over the stadium and Keith plays the quintessential guitar solo of his career. The sound is so good that the stage doesn’t ever dwarf the band. “Ah,” says security man J.C., “the band is bigger than the stage.”

Mick Jagger: We could have done even more wonderful things, but technically we can’t implement them because it’s a touring show—which has its own power and momentum. The problem with the set is you have to pick it up and move it every day. If we had a set we didn’t have to move, we could have sat it in Shea Stadium for three months, which is my idea of a really good tour. Unfortunately, it’s not very convenient for the public.

SPIN: What on earth are you going to do with this stage afterwards?

Mick: This is always the wonderful question. I have in my house in France several bits of old stages going back to 1975. We’ve tried to give the lotus one to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame but they’ve got nowhere to put it.

After-show party, the Washington Room, Four Seasons Hotel, Philadelphia: Alan Dunn sips champagne and discusses the possibility of getting the band into New Orleans by train, and into Miami by boat, just to change the routine of the chartered 727. He says it costs $3.00 per bag to get baggage in and out of each hotel; there are 35 hotels and 160 bags, that costs the Stones $16,800 for baggage alone—not including the full-time baggage handler who travels with the 45-person entourage. Dunn, who in Robert Greenfield’s book STP: A Journey Through America with the Rolling Stones, was described as “an island of calm in a sea of craziness” says, “You have to accept that it’s often going to be total madness, and no matter how well you plan, it’s going to go awry somewhere. But there’s always another airplane, another car. And there are so many crazies around that I always figured they didn’t need another one. You can always find a number of crazies, but how many calm people can you find?” He is asked what Stu would have thought of this stage. Sticking out his jaw in a perfect Stu imitation, he mutters, “Probably would have said, ‘Goddamn waste of money.’”

Keith Richards: The problems of the last few years that we had were because of a personal conflict between Mick and me, added to overwork, and just being stuck together for so long, and with Stu dying. There’s a point where no matter how well you know each other, it takes a long time to grow up, and this business does tend to put you in a perennial teen mode, whether you like it or not. It’s still too close for me to say who grew up in which way or at what different rates of speed, but I do know that you learn a lot working on your own. To be the front man just for three weeks on the road is enough to convince me of the difficulties of the job. I may not always agree with the way Mick dealt with things, but I understand a bit more about where he’s coming from. This is a great year, because we made a good record out of nowhere and nobody really expected it. And even with such a large gap from the last tour, it’s amazing how quickly everyone slipped into it. I’ve never known this band so prepared to do something in my life, unless you’re talking 1964 or 1965.

SPIN: Is there less pressure on you during a Stones show than during your solo tour?

Keith: No, because every time you walk out, the pressure’s the same. It doesn’t matter whether you’re the front man or the guitar player, or whatever. It’s “get the fuck out there you goddamn cretin, get your frock on and go.”

Pittsburgh, Three Rivers Stadium: Living Colour—who have been received enthusiastically by the crowd at every show so far and who will win all the MTV Awards they were nominated for tonight—watch the Stones soundcheck. So do all the yellow-shirted stadium security guards, who burst into applause when the Stones finish. Security staff Bob Bender, Joe Seabrook and Rowan Bade man the backstage area while Mick’s assistant Miranda Guiness checks that the humidifier is on in his dressing room. J.C. tidies up the food on the table in the hospitality lounge. This is a man who during the Stones’ after-show getaway instructs a staffer to sweep up cigarette butts and gum wrappers on the floor in the path of the band. Shelly Lazar, whose title is Ms. Tickets, or Duchess of Ducats, compares her job this tour to others she’s done for the Amnesty International tour, Bruce Springsteen, Elton John and Billy Joel. She handles over 75,000 tickets for the Stones, their staff and crew, CBS Records, MTV and the media. Her biggest beefs: People who pay with nickels and dimes (“Pennies I don’t take,” she says), and lines like, “I’ll even pay for them,” “Are these the best seats,” “I need to sit near my chauffeur,” and “I was disappointed in my seats.” “When someone says that,” says Lazar, “I make a mental note, and make sure the next time they indeed will be disappointed.”

Charlie sips coffee, Keith plays pool, and his manager Jane Rose displays a new set of earplugs. “I’ve been wearing those onstage,” says Mick. “It’s because of her boss,” he points to Rose, “he plays too loud. One night when he turned down, I ran over and kissed him onstage. He had no idea what I was doing.”

“Shelly,” says Jane, “my cousins are upset, their seats collapsed.” “I know a good doctor in Brazil,” retorts Keith, who has spray-painted his sneakers silver. He plays pool as Mick stands by the jukebox and listens to “Fancy Man Blues,” the B-side of the “Mixed Emotions” single. A perfect blues rendition, Jagger sings it like some great black bluesman, and his harp playing is impeccable. “He’s not thinking when he’s playing harp,” Keith says, “it comes from inside him; he always played like that, from the early days on.” Keith leans over to Mick and laughs, “Bill [Wyman] thought it was Jimmy Reed the first time he heard this song.”

Sitting on one couch are Shirley Watts and Tony King, who, when told that there is a huge sign in downtown Pittsburgh that reads “Pittsburgh: The World’s Most Livable City,” retorts, “Maybe for the world’s most boring people.” Then he adds, “It’s been quite a quiet tour so far. Charlie and Shirley and I go for dinner, then we go back to their suite and have some chamomile tea, then it’s off to bed early.” What? No hot milk? “Well,” he says, “how many nightclubs do you want to go to in your life?” Pointing to a group of radio people who have been paraded in to “Meet and Greet” the Stones, King says, “I think they expect to witness some bacchanalian orgy in here, and then it’s just Shirley chatting and a quiet game of pool. It’s all a bit drawing room, isn’t it?”

Bill sits on a couch, wearing turquoise blue shoes and a matching jacket, and mustard colored slacks. How do you feel, he is asked. “ ‘Orrible,” he mumbles, “I can’t sleep.” “He’s a married man now,” says Keith, “and Mandy’s not here, and Bill’s trying to sleep alone. And he can’t. He’s never done it. Well, not since he was little, anyway.”

Mick yells across the lounge: “Bill, Lisa wants to know if you’re going on in those shoes?”

On the 1975 tour, Mick Jagger—with the assistance of Alan Dunn, put ice and eggs in my bed, nailed a mattress to the outside of my hotel room door, put a frog in my typewriter and a hamburger in my handbag. Stones tours in the past tended to be on the raucous side, but this one—albeit in its early days—seems far more subdued, more mature, more disciplined. Certainly everyone is older, and more settled. There’s the occasional trip to a restaurant for dinner, Mick saw Elton John’s concert in Chicago, Charlie and Shirley celebrated their silver wedding anniversary in New York City, and security man Rowan Brade married his girlfriend Jacqueline in-between shows in Syracuse at the Hilton Hotel.

Sitting in his suite in the Pittsburgh Vista International, with classical music on the CD player, Mick drinks Evian water and says, “I’m more disciplined than I was before.” How long can he keep this up? “Till December 19th,” he laughs. “I did it on my solo tour in Australia and Japan, and there’s no reason why I can’t do it here. I train pretty hard and try to stay in shape; it’s just like being on the tennis circuit without the coke.”

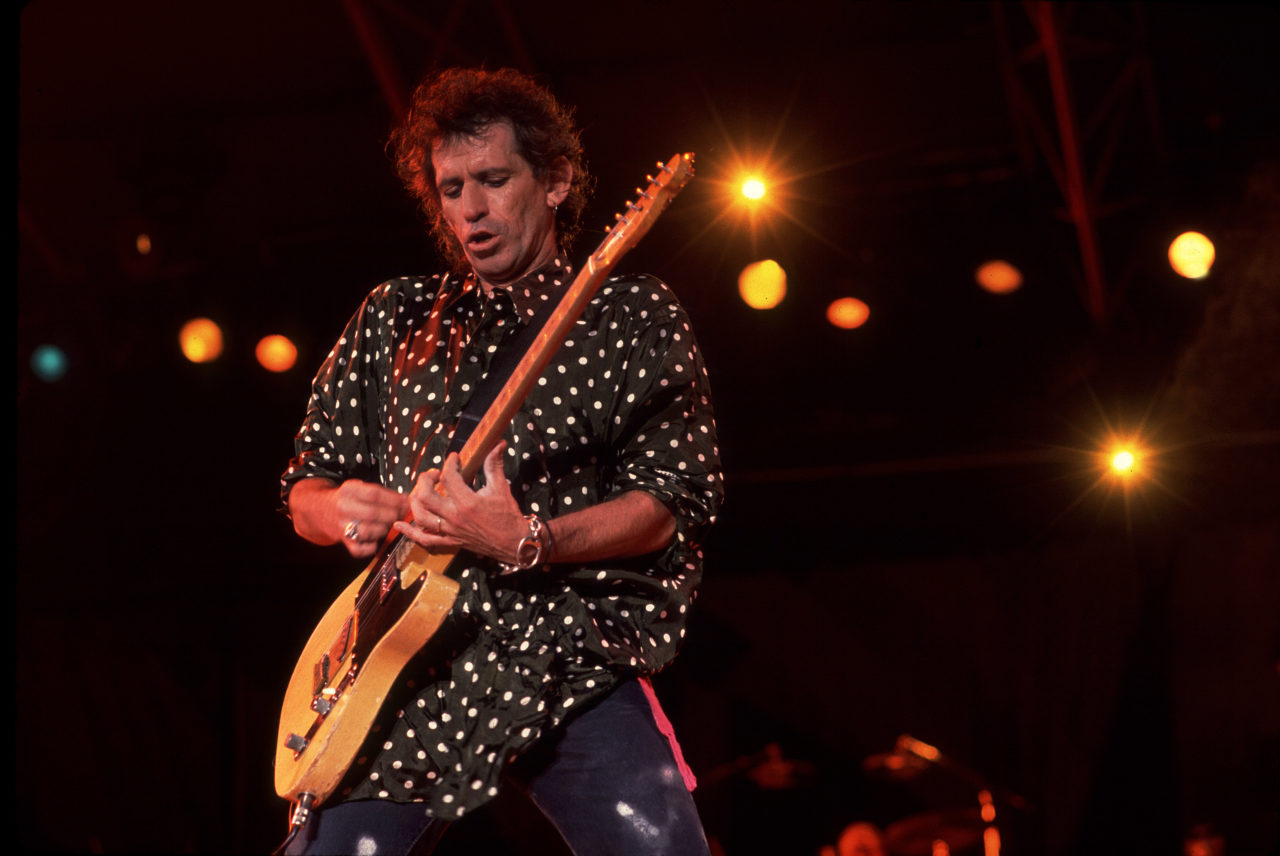

Ian Stewart, 1975: You’ve got to admire Keith in many ways because he’s so single-minded. He’s really the pulse of the Stones, and he leads the band and he’s never displayed any flashy guitar techniques or anything. Keith is the best rock’n’roll guitar player there is, yet people don’t realize it because he doesn’t do a lot of solos. He’s always left gaps and he’s great at tempos, and when it comes down to playing onstage, he’s unbeatable, really.

In 1975, Keith Richards’s hotel rooms tended to resemble Moroccan hashish palaces. Scarves over lamps, dim lights, music blasting and vampire hours. In 1989, in the Pittsburgh Vista International he still has the heavy artillery speakers—this time with the Steel Wheels CD blaring forth—it’s after midnight and he’s still up while most of the others in the entourage are asleep, and there’s a Mexican blanket covering the sofa. But the lights are up as he hosts Jane Rose, Bobby Keys, backup singer Bernard Fowler, and myself. Wearing a little porkpie hat that makes him look like he’s out of Damon Runyon, and his favorite T-shirt that reads “Obengruppenfeuhrer” (“It means ‘leader of the troops,’ ” he swears), Keith is always the hipster with the cigarette, the glass of whiskey, the Lenny Bruce wit and his own brand of openness, warmth and cynical humor. He talks… about the Who:

“Tommy was always awful. Pete did it again for the money, but I don’t think he thought he’d have to explain it so often.”

On Roger Daltrey:

“Oh my God… if you ever want to torture me, put me in a room and have him sing at me, alone.”

On Ringo’s summer tour:

“He has some good musicians but without John [Lennon], it doesn’t do anything for me. Paul [McCartney] certainly doesn’t, and I never could take George’s guitar playing. Mind you, he can’t stick mine, either. But he has done something really interesting with his life, and he’s done wonders for the British film industry.”

On “Continental Drift,” from the Steel Wheels LP:

“I made that metallic noise at the beginning of the song with a knife against a bicycle wheel. I suppose you could do it with a spoon. But it wouldn’t sound as good as it does with the knife. Kids, don’t try this in your own homes; these men are trained professionals.”

“You cannot deny the Stones,” Keith Richards said to me in September 1988, when he released his solo album, Talk Is Cheap. “Even if the Stones never played another note in their lives, Mick and I still have to deal with each other for the rest of our lives with the business of the last 25 years. We can’t even get divorced; it would be easier to do that with an old lady than to do with Mick, but we can’t get out of it so we might as well learn to live with each other. We’ve just got to. I see it as growing pains; whereas Mick was afraid the Rolling Stones could turn into some sort of nostalgia dead end, I see the Rolling Stones on the cutting edge of growing this music up and the only band in this position to do it. Listen darling, this thing is bigger than both of us.”

The Rolling Stones have grown up: they are no longer rock’s bad boys and have willingly passed that title onto a new generation. But even if it seems a bit “drawing room” backstage on the Steel Wheels tour, onstage the Stones are still the best juke joint band in the world.

Will this be the last time? “They’ve been asking us that since 1966,” laughs Mick.

Ian Stewart, 1975: I stayed with the band at first to get away from the office where I had been working. And I still liked the music. Once they got out of London, the screaming thing happened and it was a hoot to watch all that go down. They’d do 20 or 30 gigs in a row before they’d get a night off, and you’d drive up and down the M1 and meet all the other groups and it was great fun. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. And on a good night, when the concert really swings, you just realize how good a band they are, and that really gets to me.

Leave a comment