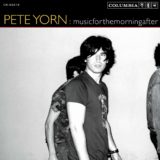

Tomorrow (March 27), Pete Yorn will celebrate the 20th anniversary of his debut LP, musicforthemorningafter, which (for obvious reasons) holds a special place in the singer-songwriter’s heart. Joining forces with producer R. Walt Vincent and later, Brad Wood, Yorn went into a San Fernando Valley garage and knocked out one of 2001’s best.

After the seeds were planted with his 1996 move to Los Angeles (his two brothers work in Hollywood), the New Jersey-born, Syracuse-schooled Yorn was quickly recognized as one of his generation’s best songwriters. The album catapulted him to early success, allowing him to carve out a career without compromise and remain true to his personal ethos, especially with the music business in great flux.

During the pandemic, Yorn has taken a long look back at his career. He recently released a covers project, performed his old albums in full on livestreams and on May 5 will release the Rooftop EP, which includes rarities and live tracks from the musicforthemorningafter era.

To celebrate the anniversary, we spoke with Yorn at length about the making of that pivotal record. And although it’s not quite 20 questions, we got a great sense of his mindset two decades ago.

SPIN: When did you start working on musicforthemorningafter?

Pete Yorn: I was done with it before it was released, I think in 2000. It sat for a year before it came out. And the beginnings of it started probably in ’99.

A lot has certainly has happened in the 20 years, at least for you, since the album was released.

It’s 20 years of energy wound up. I’m 46 now, and in 20 years I’ll be 66. But right now, being cliche, I’m trying to stay in the moment and enjoying it.

What are some of your memories of making the album?

I was so proud of it. I remember when I was making it, I felt like I didn’t compromise anything. When I got signed to Columbia, I got these opportunities to work with these super well-known producers — people who were hot at the time. I just had something really special going on with my friend Walt, who hadn’t really done much before then. We were just working in his garage at the time on a computer, which wasn’t that popular yet. We just really loved what we were doing and getting excited about it — and we were having fun. It felt effortless.

How so?

It felt like that covers record did — this fun, effortless combination of two friends making music. That’s the way I like to work. I remember resisting, once we got signed, the urge to go work with other people. I really just liked what we’re doing and I was going to just take that chance and make it how we’re making it. Then we did bring in Brad Wood. To his credit, I remember he heard the early mixes with a lot of the stuff that we had that would end up on the record. Brad just got it. I remember he said, “Well, I really love what you guys are doing in the garage. I don’t want to mess it up. I just want to come in and help you guys keep going.”

What were some of the pitches from other producers?

They were like “Oh, we need to do this and that.” I remember just like Brad being the guy who gets it. That was really cool and I remember it clearly. We just continued working and kept going.

What was your thought process and internal direction at the time of the recording?

I remember thinking in my head that I just want to make something that I’m still proud of in 10 years. And now we’re at 20, I don’t listen to that record and cringe. I never get tired of singing those songs.

At the time the record was released, singer-songwriter stuff wasn’t really that prevalent on a major label level. It was dominated by boy bands and hip hop becoming what it is today — not to mention the Strokes and the White Stripes were starting to emerge. How do you think that allowed musicforthemorningafter to stand out and how do you think that timing helped?

I remember I bumped into Little Steven [Van Zandt] at a restaurant. I didn’t know him, but I was just a fan. I think I just got signed to Columbia, and he was like “You should do a band name, do a band name.” I thought about [using a moniker], but I naturally ended up just using my own name. I always felt like musicforthemorningafter could have been a band record. It could have had that feel even though I played all of the instruments.

But it does have that feel…

I love Britpop so much, like the Smiths, Oasis, the Cure, Stone Roses, Ride, Blur all that stuff. I was also, at the time, a huge fan of roots-rock Americana, the Band, Neil Young, Beach Boys, Bruce [Springsteen] of course. [The album] sounded like it felt like more of an alternative rock record in some aspects — even though there were quiet moments — than like even the typical singer-songwriter record, or at least the idea of that.

What about for touring? What did you do to bring that element to life in a live setting?

I wanted a tight rock band. Most of the band were just old friends. I remember I really wanted a drummer as someone who was able to lock in on a click, but could also swing really hard so you didn’t feel like it was too rigid. I was obsessed with Keith Moon, but I also love electronic, so I wanted to have the balance of both. I think we auditioned 60 drummers for the live show. We found one we loved, then like two days before the tour was supposed to start, he had to leave the band because he got signed up on his own project he was on. Luckily, we found this kid Luke Adams, who ended up being our touring drummer for a couple of years.

Was there anyone or any vibe you were channeling when you were prepping for tour?

I always thought it was a little bit more rocking than the typical singer-songwriter cliche. There were other artists like that who did great stuff and were doing some pretty interesting rock and roll stuff that hit harder than a typical folk album. Morrissey had that [sings] “I thought that if you had an acoustic guitar that meant that you were protesting.” That pops out in my head. Just because you’re playing three acoustic songs doesn’t mean you can’t have this other side that wants to explode as well.

What were you listening to at the time when you were recording?

Guided by Voices! I was turned on to GBV in 1996, when I graduated college. When I moved to L.A., I found myself listening to a lot of GBV. In fact, on all my early demos, I would do a four-track recording by myself. I was just into that lo-fi sound. I was also really into Son Volt and Wilco, though I never got into Uncle Tupelo. Also, Teenage Fanclub. I was huge into them. I wanted my record to have a twist. I didn’t want to do a straight alt-country record because I felt like it wouldn’t get as much mainstream acceptance if it was that. I also remember being into Electronic with Johnny Marr and Bernard from New Order.

So that was imprinted, at least subtly, into the album?

Yeah. I remember loving that single “Getting Away With It.” When you hear “Black” and you hear a song like “Just Another Girl,” you can hear it. I remember thinking when I finished the record that I thought it was all over the place, but that’s who I am, and I didn’t know if people were going to get it or not. But I liked it, and that’s all I could do. It was almost a joke. It’s like a melting pot — like if I’m throwing in all my influences in a way that I feel is still tasteful, it’ll somehow become its own thing.

How difficult — or easy — was it to play everything yourself and create a bigger sound?

I couldn’t have made that record without Walt and Brad Wood. Those guys were able to help me bring into reality the things that I heard in my head that I wouldn’t have been able to do on my own. Of course, I was able to play a lot of instruments, but they played some great instruments to parts that accentuated my parts and made what I played even better. They would bring a lot of emotion. Walt was a master of beautiful strings. I love that sound.

How so?

He would bring that extra emotion out that I was feeling inside. I remember always just being like, “Wow, such a beautiful extra arrangement on top of this acoustic and bass and drums” or whatever that I had laid down. Those guys were such great partners. Over the years of working with great producers, I feel like that’s always what they add. They add to what I do in a way where they kind of bring a basic thing to my elements that are playing, and they add this color to it. When we have a successful recording, that’s usually what was brought to the table by some of the great producers that I’ve worked with.

What was it about Walt and Brad that made this what it was?

When I met Walt, he was like “Well, let’s try something.” I’m like, “Well, I’ll just lay the basic tracks and bring it to you. Let’s see what you can add to it.” I went to Walt with a CD file of “Just Another Girl” and it was just bass, drums, vocals, and acoustic guitar. I go to Walt’s, and he pulled it up and added this beautiful synthesized sort of stuff behind it that sounded real but fake at the same time. Then he added the harmonica at the end of the crescendo at the last chorus and put a mix on it. I remember leaving his house that first day — it was just a little garage studio he had. I put the CD-R of it in my car, and I’m driving home from Van Nuys. I don’t know if I pulled over or what, but I was just like, “Hoolllllyyyy shit. This is something special.” Talking about right now, I just got a chill about it. That’s what started it off with me and Walt. Then every other week, I’d go over to Walt’s and we’d do another song, another song, another song. And then from those first recordings, Columbia jumped on board. Then later on, we brought Brad in to help us clean up and tie the room together.

What was it like working digitally when people were still using tape?

There was a snobbery about it, I feel like. It wasn’t even Pro Tools. It was this digital performer called Motu Mark of the Unicorn. Walt had it, and I remember saying “What is this crap?” I recorded the bass, drums and acoustic guitar on Pro Tools in my basement at home with my friend JJ. I was like “What is this like Pro Tools or digital performer?” It seemed so nerdy to me to record on the computer when tape was like everything. But I quickly learned that it’s not the car, it’s the driver. There’s tons of records from the ’80s that are all tape and they sound like shit. Ultimately, though, Brad Wood was very adamant that we bounce it all to two-inch tape and he’d mix off of that.

How did that work?

We recorded everything in the garage, but we mixed at the Record Plant. When Brad mixed it, it was hard to beat the rough mixes, because the rough garage mixes really had a good feel. If I lost the feeling — not so much the sound, but the feeling I would get when I hear it — and I started to go numb, then we have a problem. The first few passes, I remember, we weren’t feeling it. Then something clicked with Brad and he just started nailing it. He nailed all the mixes, and I think the only song that was the rough mix on the record was “Lose You.” There was just something about one of the early rough mixes of it that just had this magic.

How did soundtracks and licensing your songs help keep the album going as long as it did?

That’s a great question. You know, at the time, it was crazy. We had the opportunity to have it in so many shows or movies. I don’t know if the early 2000s were the heyday of licensing or whatever, but certain placements were a great entryway to discover my music for sure. I feel like without the work that I did on top of it, it might not have amounted to much, but I think there were good opportunities. I think there is no supplement for my non-stop touring that I did. I toured for 18 straight months on that record. We just kept going and going and going which burned me out by the end of it. I think just bringing it to people and getting out in front of people ultimately was the biggest thing, but the soundtracks — especially when it was a powerful moment — it was always a beautiful thing.

Leave a comment