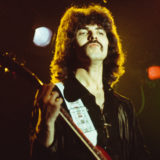

As one of rock’s most legendary guitarists, the creator of the ominous riff for the song “Black Sabbath” — not to mention the soundscape of the ubiquitous chant-along “Iron Man” and many dozens of other iconic Sabbath songs, Tony Iommi is one easygoing, unassuming bloke. His melodic sense has even led some to term Sabbath “The Dark Beatles.” Iommi, 73, has been a constant throughout Sabbath’s eight singers, a definite aural architect of the Sabbath’s sound over 50 years.

Black Sabbath enjoyed several discrete eras: the Ozzy Osbourne years began in 1968. The first of two time periods with Ronnie James Dio at the helm started in 1980, then came round again under the Heaven & Hell moniker in 2006. (The name is taken from Dio’s first LP with his Sabbath brethren.) Recently, Black Sabbath reissued their first two albums with Dio, Heaven and Hell and Mob Rules, each set contains newly remastered audio along with rare and unreleased music.

<!– // Brid Player Singles.

var _bp = _bp||[]; _bp.push({ “div”: “Brid_10143537”, “obj”: {“id”:”25115″,”width”:”480″,”height”:”270″,”playlist”:”10315″,”inviewBottomOffset”:”105px”} }); –>

During the lockdown in the UK, Iommi has laid low: taking out a neighbor’s teacup-sized dog, and also walking and talking with a friend — though Iommi confesses they have to shout at each other due to masks and hearing loss. As for that other pandemic cross to bear — Zoom calls and performances — he confesses with a laugh, “I’m rubbish, absolutely rubbish. I’m still old school, unfortunately.”

What have you been doing during the last year guitar-wise? Do you play daily, weekly?

Tony Iommi: I just usually play every night, really. Just even for five or 10 minutes. When I go to bed. I’ve got a couple of guitars in the bedroom and I might pick them up watch the TV for a bit and play. And in the day sometimes. In the last year, I’ve played on a couple of albums. I played on one project with [Pink Floyd’s] Nick Mason. We did a charity track, which is very different for me because it was something where the lyrics are from World War One; letters of the soldiers that got killed and they had sent letters home. But they never came home. A guy decided to make a project of the letters and put them into a song. I quite enjoyed that; it was very different for me. I have been writing. I’ve got loads of different ideas. But again, you can’t have anybody in your house at the moment. And I can’t work without my engineer, I’m totally lost.

So, for Heaven and Hell, the first Sabbath record for Ronnie in the band… I know Sharon Osbourne introduced you two. Did you already know him from Rainbow or Elf?

I’ve never met him before. I’d obviously heard him with Rainbow. I thought, ‘wow, God, he’s a great singer.’ Never thought for one minute I’d end up being in a band with him. She introduced me to him at a party. Remember those?

Ha, barely! Had she introduced you with the intention of you guys playing together?

Well, it was sort of mentioned because it came to a point within Sabbath where it was getting a bit sort of… I just wanted to do something. And we were coming to a bit of a halt at the time because of the situation [Ozzy’s partying]. I did mention the idea of doing something solo, as a different project. Ronnie was interested in that. And then when it came to when Ozzy was no longer with the band, I called Ronnie and said, ‘do you fancy coming over and having a play with us?’ He came over and the idea was just to have a jam, really. We did, and we were all impressed with what he did. And he liked what we did. It sort of went from there, really.

I know you worked at Criteria in Miami, home of the Bee Gees… how did you end up there to record Heaven and Hell? And, part two, there’s the story you lit drummer Bill Ward on fire… was it there?

Stop making me laugh! No, it wasn’t, actually, it was in London where I set him on fire. We had recorded at Criteria with Technical Ecstasy [in 1976]. We were in Los Angeles when it all blew up with Ozzy, and Don Arden [Sharon’s father] managed us at the time, and he was very difficult, and we were breaking away from him. So we didn’t want to stay in Los Angeles any longer. The idea was, ‘well, let’s go to Miami,’ so we went and stayed at Barry Gibb’s house. And wrote the album, really.

So with the new versions of Mob Rules and Heaven and Hell, are you the point person for the band? The one who says ‘let’s use this live version’ and approves the mixes?

I think maybe Geez will have a listen. Wendy [Dio] may be involved somewhere, but they usually ask me first, so it’s my fault if anything happens. Of course!

I feel I should know this, but I don’t know the story behind the Mob Rules track “E 5150″?

Yeah, that was just basically a bass intro; Geez [Geezer Butler] was responsible for that. I just put a bit of a guitar on it. It was for the Heavy Metal movie. And they wanted this effect thing, where all these monsters were walking, were changing, and they wanted some music to go with that. That’s why that was recorded. We recorded that actually at John Lennon’s house. In his studio, it was 5150. We put that together there. We went there to record [the song] ‘Mob Rules’ and to use the studio and use Lennon’s engineer, too. To put the soundtrack down for the movie… So we’d done ‘The Mob Rules’ in there, but then they wanted this intro.

I’m trying to do my math; had Lennon just died at that point?

No, he’d been dead a while. But the house was exactly the same. I don’t if you have ever seen the ‘Imagine’ video where you’ve got the white piano. That’s actually where we wrote ‘The Mob Rules,’ in that room. We set the gear up and it was all Lennon’s gear as well; we didn’t have any of our equipment. I used a Vox AC 30, which was there and Geezer used a bass amp which was there. We actually had two versions, ‘The Mob Rules’ version for the movie, and then when we did the album, Martin Birch, who produced it, wanted to have it all more in sequence, so we needed to record it all again. We were like ‘oh, no,’ because we liked the original version. It sort of has the energy, you know, we have a different vibe there. But we had to do it again. But we did put the other version out as well.

When we spoke of “E 5150” on Mob Rules, of course, I thought about that being the title of a Van Halen album. Do you remember the first time you met Ed or saw him play?

Eddie was a really close friend of mine. We stayed in touch since the first tour, since 1978. They came on their first World Tour with Sabbath. They were all itching, all ready to go. I really liked him. I’d never heard anything like it, the way he played, I was, ‘Wow, this is really different.’ We got to know each other; they were out with us, for I think, eight months. We used to get together certain nights after the gig or a day off. He’d come around to my room, and we’d play a bit and chat; he was really interested because they were all new to it. He’d be, ‘tell me what happened after this, and where did you do that?’ He was really interested in stories. He used to sing some of the Sabbath songs when he was in the band before [Van Halen]. We had some great times. And we stayed in touch. We lost contact for a while. I saw him again and we exchanged numbers again. I used to meet up with him when I was in LA, him and his wife, myself and Maria. We’d go out to dinners. He really did stay in touch with me a lot. You know, he sent me some great emails.

Did you ever try the hammer-ons and all the crazy things Eddie was doing on the guitar?

No. In a word! [Laughs]. I mean, he was so good. And he got absolutely amazing at that stuff. Oh, man, I couldn’t do it. I had tried. But again, when somebody’s done it, to me, I don’t wat to be going around doing it; ‘oh Eddie Van Halen already does it.’ But I couldn’t actually do it. To be honest, it just wasn’t my style of playing. What he did was just brilliant.

Did you guys speak about collaborating? I know, two guitarists, no singer, but did you speak of that?

When we used to go out for dinner, we’d always end up [grousing] about the bands. He’d be going on about Dave Roth, and I’d be going on around about [whoever]…. This was just before he died, or rather, before he really became ill. And he helped me a lot as well. Because he went to Germany for some stem cell treatment on his hands; he had problems with arthritis and stuff. And I had a problem with my thumb. He said, ‘why don’t you go see this guy of mine who I’ve been to in Germany, in Dusseldorf. He arranged it for me and I went and got this sort of topical stem cell treatment, which helps. Eddie used to go back and forth for different things. I know he’s been ill with his cancer on and off for years, and I’d see him through the different stages. We’d go out to dinner and he’d talk about that. We’d talk about music and talk about different things. Piss and moan about stuff, you know.

Did you get a chance to say goodbye to him?

Well, I knew it was a matter of time. But he did contact me. And I could tell. The last email was just before he went into hospital the last time and it was really… You know, some of the words were mixed up, he was obviously sedated or something. But that was the last one I had from him. I really miss him.

Wolf’s [Van Halen] debut album is coming out. You know, he had so much success with that single for his farther, ‘Distance.’

Eddie idolized him. You know, he really did. We used to talk about Wolfie quite a lot. And when we played in L.A. last time, they all came. Wolfie and Alex and Eddie and the wives. I got some great photos with us all. it was brilliant. I got Eddie down to rehearsal when we played in England one time. He said, ‘what are you going to do tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Rehearsal.’ He went, ‘ah, great. I’d love to come to that or come down.’ I went and picked him up at his hotel. On the way past the hotel, I popped into the music shop and asked, ‘Have you got an Eddie Van Halen guitar?’

They said, ‘Yeah, why?’ Of course. I brought Eddie in, and they were in shock. I asked if we could borrow it for a few hours here. they said, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure!” I’ve got some tapes of that rehearsal.

I know you’re great pals with Brian May. And the Bohemian Rhapsody movie was such a success. Has there been talk of ever doing a Sabbath movie along those lines?

Yes, there was talk of it, and I don’t know what happened. It sort of went out the window when all this thing [Covid-19] started. But we were talking about probably 18 months ago, about doing the biopic. I haven’t heard much else.

Was the final Sabbath show in Birmingham, U.K. on Feb. 4, 2017, the last time you played live?

Ummm….We’d done the two shows, then I suggested to the others, ‘we should go into the studio and re-do some of the older stuff in the studio that we’ve done on stage.’ So eventually that came together, and we did it, and we filmed it. There are certain songs that obviously [Ozzy] wouldn’t sing on stage, they’re just too high for him. He used to sing so high at certain times. When you’re 20, it’s not so bad, but when you get to 70, it’s a bit difficult, really. He could probably do one, but in a set, it couldn’t work. So I suggested we go into the studio and just re-record a live thing there, which we did. Four or five different songs which we haven’t played for years, which was good fun. And that was the last thing. I didn’t want to end it on just the two shows, because you don’t get a chance to get a proper goodbye and hang around, because you have all the press afterward, and all your friends. So it was nice, two or three days afterward, just seeing each other in the studio and saying goodbye.

Was that with Rick Rubin?

Uh, no. [Laughs.] Just us. [Rick’s] another story. He’s very different, I must say.

Did you learn anything from Rick?

Yeah, I learned how to lie on the couch with a mic in my hand and say ‘next.’ [Laughs] It was just different, the way he works. He wanted to find the original Sabbath sound. He said, ‘have you got your original amps?’ I said, ‘Rick, that was 50 years ago. Do you have any amps from 50 years ago?’ I said, ‘I don’t have them, they’ve blown up. They’re gone long ago. I’ve got my own amps now.’ He said, ‘no, we need the old stuff.’ So I get to the studio and there are 20 different bloody amps there. He goes, ‘they’re vintage amps.’ I said ‘that doesn’t mean they sound good, they’re just old.’ He went, ‘well, let’s try them.’ I tried them and I didn’t like any of them. So it was a bit of a backwards and forwards til he got used to me, and I got used to him, really. But we did it, and the album was very basic. I’d done a lot of the songs from the last album in my studio at home. I thought the sound was better, to be honest. But there was more stuff involved; I put more instruments on it. He just wanted it very bare and very basic, which you know, was good.

Leave a comment