Cleveland’s Coventry Village, a neighborhood lined with vintage shops, restaurants and bars was once the hippest area in the city. Located in leafy Cleveland Heights on the city’s east side, the once-bustling area has been quiet since the pandemic hit. Few more so than one of the area’s few constants: independent music venue The Grog Shop.

Nestled between a movie theater and coffee shop, The Grog Shop’s exterior makes you think you’re entering a restaurant or café, not one of the best concert venues in the Midwest. It can go toe-to-toe with such other regional tastemaking venues as the Empty Bottle in Chicago and Magic Stick in Detroit. Yet once the door swings open and you pass security, it just feels like a music oasis. Dimly lit with sticky floors and a barely-above-ground stage, The Grog Shop captures the essence of what a great music venue should be.

The first step to stardom

First opening its doors on the other end of Coventry in 1992, The Grog’s history is power-packed with artists on the brink of superstardom playing its stage. Oasis performed there on their first North American tour in 1994 and the hits just kept on coming: Elliott Smith in 1997; a babyfaced Conor Oberst took Bright Eyes there in 2000 as did At the Drive-In; a memorable Bob Mould show in 2008 where 50 people braved a blizzard to see the former Hüsker-Dü frontman perform; and during a three-year stretch on Thanksgiving from 2008-2010, the venue hosted a murderer’s row lineup of regional hip hop powerhouses Kid Cudi, Wiz Khalifa and Machine Gun Kelly. An on-the-brink Bruno Mars played there in 2010.

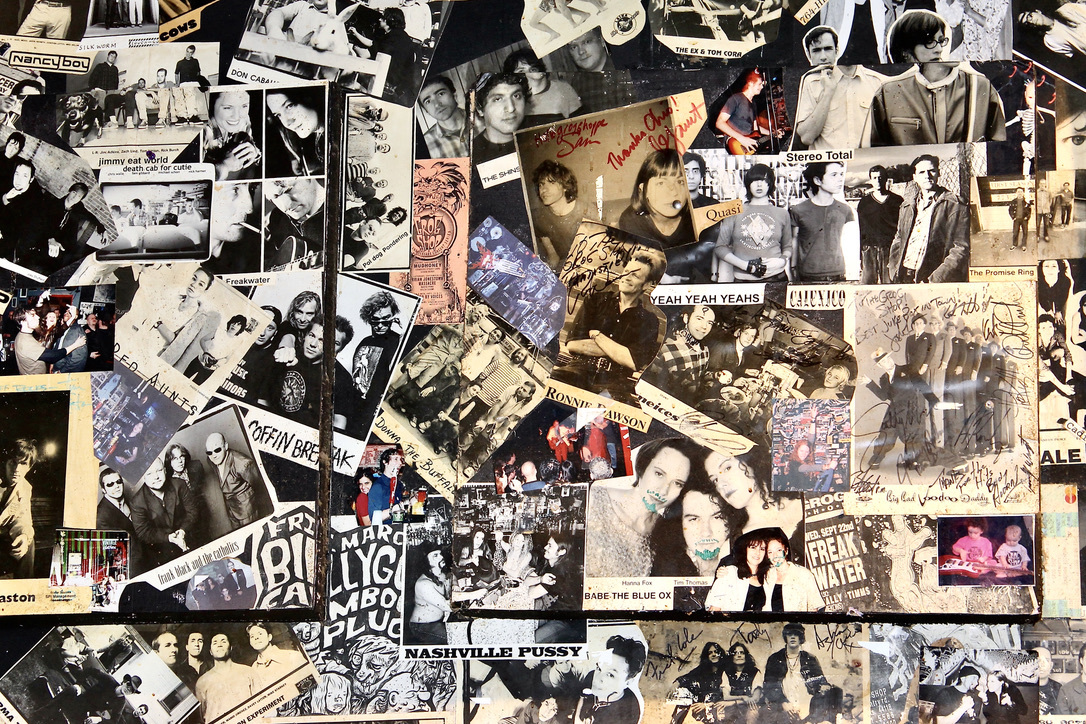

Walking into The Grog, it’s eerily quiet and when you look up, its concert calendar from March 2020 remains on its upcoming shows listing, adding a different ominousness. With its 420-person standing room capacity, the room has the rare balance of being at once intimate and spacious. On a cold winter afternoon, owner Kathy Blackman, a petite energetic middle-aged woman with long curly black hair, who has been the club’s owner since its beginning, should be directing her staff to prep for the night’s show: making sure the sound is dialed-in, the bar stocked and merchandise ready as bands file in ahead of the crowds. But this is the era of COVID, and only Blackman and venue manager John Neely are around in the venue’s office. The duo is working on booking shows for fall 2021 and early 2022, waiting, like the rest of the music world, for a time when things will go back to normal.

As the spring became summer, fall and now winter, and with another spring on the horizon, Blackman quickly adjusted. She’s managed to buckle down and keep costs and utilities tight while planning for the time when bands will hit The Grog stage again. Prior to the pandemic, The Grog was a self-sustaining entity: cost-wise, the little things would never have been a consideration.

“I obviously paid all the bills and did all that, but you never think about, ‘Oh, my God, how, what exactly do I need to make this month.’ I’ve never lived that way,” Blackman says. As the pandemic wore on, she had to pare down expenses to the bare minimum. The venue’s cable, phone and partial internet, waste removal have been cut down to a fragment of what it was.

In the past, Blackman has had offers from Live Nation to align with The Grog but she’s always declined, keeping her venue’s character unique. By keeping The Grog independent, she’s been able to foster an environment that’s beneficial to both emerging local and national artists. If it was to close, it would leave a missing step on the Cleveland music ladder.

“There’s super DIY, like the warehouse space, right in somebody’s basement,” Blackman explains of the scene’s venue hierarchy. “And then there’s The Grog Shop. And then there’s the next step. This is sort of the last real element of live music for bands as they develop. So if you miss The Grog Shop step, you miss a lot. If you lose the small, intimate experience of the clubs, you’ve really lost everything.”

Despite that, Blackman remains cautiously optimistic that things will start to turn around later this year. “When things start coming back, the little clubs will be the gem,” she says, “because people will be comfortable. We will be here for them no matter what. But will this touring scene thrive again? That’s a big one.

“People remember the show at the old Grog when there were 150 or 200 people and you’re all on top of each other sweaty, more so than you remember an arena show at Blossom [Blossom Music Center in Cuyahoga Falls, an outdoor amphitheater which holds 23,000 people],” Blackman says. “The feel of seeing any of these bands that you’ve loved over the years is how you remember the early Grog Shop shows. I can’t believe it will go away. I just have to believe that it’s important enough to enough people.”

A little help from their friends

As we talk, the payment processing machine starts going off. At first, it makes for a slight inconvenience when trying to talk to someone six feet apart. But it went on and on and on for about five minutes, all for merch sales — The Grog’s community has responded. Blackman will occasionally sell Grog swag at events and the support has been overwhelming. She knows that the artists are the lifeblood (in addition to a great room and a killer beer list) to what makes The Grog, well, The Grog.

Last November, the Cloud Nothings swung by The Grog and recorded a livestream for their 10th anniversary. The band’s singer-guitarist Dylan Baldi notes how instrumental The Grog was in helping the band grow as a live unit and others wouldn’t have the opportunity to grow and nurture a fan base if smaller venues disappear.

“Music is a historically important piece of Cleveland,” Baldi says. “Obviously, it would be a huge hit to the city’s music scene if we lost important venues that are institutions at this point.”

The Cloud Nothings has a long relationship with the venue, having performed there a dozen times and their loyalty and appreciation to where they began is something not lost on them. With a new album out on Feb. 26, the Cloud Nothings will be airing that livestream at The Grog on Feb. 27.

A ballroom blitz transforms a neighborhood

Across town on the other side of I-90, the Beachland Ballroom & Tavern has also played an integral part in Cleveland’s thriving music scene. Founded in 2000 by Cindy Barber, a bespectacled woman with short gray hair, and Mark Leddy, a burly, graying middle-aged man, the duo took Croatian Liberty Hall in the city’s Collinwood neighborhood and turned it into a music venue that features a smaller tavern in the front and a ballroom in the back. The Beachland’s existence helped turn around the neighborhood. Before, it had historic buildings, but it wasn’t a vibrant neighborhood. Today, this stretch of Waterloo Road has several blocks of a bustling arts community that includes a multitude of bars and art galleries and the record store Blue Arrow Records, with the Beachland serving as its heart.

A week before everything was shut down, the Beachland celebrated its 20th anniversary, no small feat considering the litany of problems that the old building has given Barber and Leddy over the years. That week featured shows from the likes longtime standbys of Montreal and New Bomb Turks, with the last “normal” show headlined by Squirrel Nut Zippers. “We had our best week ever,” Leddy muses as we sit in the Beachland’s chilly, empty, yet strikingly intimate ballroom.

“The reality of the Beachland is that we’ve been in trouble for 20 years trying to keep this place going,” Barber says with a laugh. Even so, like The Grog, the Beachland has become one of the preeminent places in town to catch local and national acts on the rise. It also helped spawn the growth of a neighborhood.

For the record

The Beachland’s long-time neighbor, Blue Arrow Records, is one of the great record shops in a city full of them. Located a mid-range touchdown pass away from the Beachland, Pete Guylas’ shop has managed to increase its business during the pandemic. Currently open for a handful of hours Thursday through Sunday, the tall, gray-haired Guylas expected records to be the last thing on people’s minds. Specializing in vintage and rare LPs, vintage magazines and tour memorabilia, Guylas’ sales have also benefited from a strong online presence with its own shop. as well as utilizing sites and platforms like Bandcamp (for its own releases), Etsy and Discogs. With high-priced items behind the register — adjacent to a signed 1993 L7 cover from this publication — and several meticulously organized rows and a stage on the back wall, Blue Arrow is a record collector’s dream.

“Right from the start, I was getting orders from across the world,” Guylas says incredulously as he holds his cat Rhonda in the back area behind the store, which is wall-to-wall with records and products from his Blue Arrow label. Orders have come in from all over the world, including Malta and Japan. “The only thing holding us back was fear that the post office would drop the ball.”

Blue Arrow doesn’t participate in Record Store Day and will rarely pick up new releases. “I buy some new stuff to sell in here, and it doesn’t move,” he says. “And so that tells me if I were strictly selling new stuff, that I would be stuck in the water, I’d probably be on a sinking ship.”

Other record stores in the area, who all abide by the reduced capacity limits, have adapted in their own ways, offering free delivery to customers. Stores like the Record Den in Mentor (19 miles east of downtown Cleveland) and the Vinyl Groove Records in Bedford (16 miles southeast of downtown) have had smaller capacities, but have had a steady flow of patronage throughout the pandemic.

“A lot of people really feel a lot of gratitude and ownership toward the independent record stores and independent businesses in Cleveland,” Cleveland-based journalist Annie Zaleski says. “People here are doing what they can to support that. There’s a very strong culture of supporting small businesses and shopping local and things like that so I think that’s been a strength.”

Blue Arrow’s convenient location to Beachland has made it a hub for touring musicians. “That’s a fun bonus to where we are,” Guylas says. Artists like Chris Robinson, Yo La Tengo, John Flansburgh from They Might Be Giants and Jon Spencer were regulars when they’d be in town. The same goes for crowds ahead of Beachland shows who’d trickle in to look for classic vinyl.

Since there aren’t shows right now, a lot of Blue Arrow’s foot traffic comes on the weekends. Some days, Guylas worries that the store is at capacity, which in these pandemic days, is a good problem to have.

“I do look forward to those days when you don’t have to worry about counting heads in the store,” he says with a sigh.

The ‘key’ to the Beachland’s endurance

Like The Grog, the Beachland is an independent venue and has its own stellar history. Bands like the White Stripes, the Hold Steady and the Decemberists played their first shows in Cleveland at the Beachland. More notably, a little band from Akron named The Black Keys got their start playing in the Beachland’s smaller Tavern, which holds up to 100 people.

When The Black Keys first performed at the Beachland in 2002, the only thing of notice in the area was a BP station, drummer Patrick Carney remembers. “That area totally became alive because of the Beachland,” he says.

However, things did get tight for the Beachland over the last year. Every time things were on the brink of disaster, a benefactor would step in and help out. “Some guy donated $10,000,” Leddy says. “I don’t know how we would have made payroll on that stretch because there was no other money coming in.”

“We raised $14,000 in 48 hours,” Barber says of the onset of the pandemic. “That was 150 people that just went online and opened up their credit cards because they wanted to help. And that was amazing and made me cry. Like, ‘oh my God, we have so much love.’”

“The whole scene of local music revolves around places that size,” Carney explains. “The fact is when we started out, a place like the Ballroom was just like a massive venue to everybody. The idea that we would play there was insanity. I remember going to the old Grog Shop and seeing some incredible shows there. To the average person that might seem completely insignificant, but without that place there wouldn’t have been a scene, and that to me made all of Coventry cool.”

Though still much very a brick-and-mortar operation (there is a vintage clothing and goods store in its lower level), Beachland has had a more active online presence and has been able to sell its merchandise and persist. As of press time, the Beachland has raised close to $70,000 in merch sales alone.

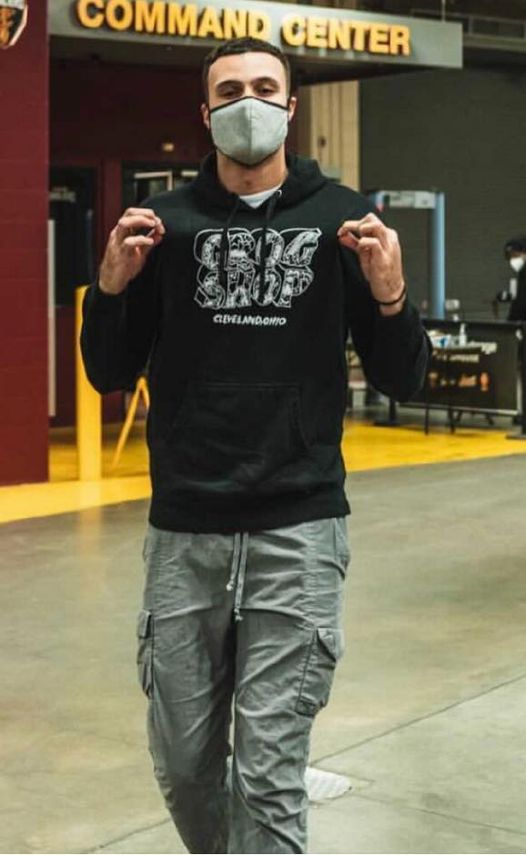

The Grog has also seen its support grow. Merch sales have been solid and the venue received an unexpected boost from Cleveland Cavaliers forward Larry Nance, Jr. Before the 2020-2021 NBA season tipped off, Nance promised to wear gear from local businesses impacted by the pandemic and auction off his jersey from the night’s game to raise money for the business he supported that game. And he’d also match whatever funds they raised. On opening night, he wore The Grog’s shirt and ended up raising $8,000 for the venue. Deciding to pay it forward, The Grog printed limited edition old-school Cavs Grog Shop long sleeve T-shirts. A portion of the proceeds from the sales went to the Cleveland Heights Schools Foundation and was earmarked for athletics.

Friends are family

After seeing Barber’s Facebook post that the Beachland needed help to fix its leaky roof, Carney sprung into action. Barber revealed that the drummer quietly donated a generous amount to ensure that the repairs were made. This isn’t the first time Carney has helped out, however, but his generosity sprung from how appreciative he is for the Beachland and in turn, Barber and Leddy were for The Black Keys. Barber and Leddy introduced The Keys to their first booking agent.

“Cindy and Mark really became like family to us early on,” Carney says quietly. “They encouraged us and gave us show after show. When I saw Cindy post something about the roof and bills piling up, I emailed her then I emailed my business manager and said to send them a check. There’s still plenty that needs to be done not just here, but other venues as well. Dan and I are more than willing to help out. We would definitely be there to [help] the places that were so good to us.”

Maintaining a relentless tour schedule is what sharpened, and ultimately, turned The Black Keys into international headliners. As the pandemic wears on, Carney notes that the trickle-down effect from labels to venues and especially indie and smaller musicians is stalled. He says that The Black Keys aren’t planning on touring in 2021 even if they are allowed to. Instead, they’re deferring to the bands who rely on touring as their financial lifeblood and are fully supportive in yielding shows to them.

However, Carney hasn’t ruled out a potential one-off Black Keys show to support the venues that helped them.

“The Grog Shop and the Beachland, they’re much more personal types of venues,” Carney says. “We really feel like artists. Even when we were complete nobodies, we felt a connection to them and support for them. You just don’t find that out in places like Nashville, it’s just different. Ohio is different. With Mark and Cindy, they were always fair and square, and when they didn’t make any money, they would give you a hot dog.”

Not so grand re-openings

After meeting all of the city’s guidelines through a drawn-out process last fall, The Grog and the Beachland were able to open for drastically reduced capacity shows that featured mostly local bands with strict safety precautions. Despite the thrill of opening its doors, both venues were barely breaking even. However, watching fans’ relief at being able to experience live music safely was worth it.

“People were completely relieved that they can go someplace and feel safe, because we were really cautious about the protocols,” Barber says of the shows that were set up in the venue’s parking lot. To stay compliant with the COVID restrictions, Barber and Leddy bought a used tent for $500, new outdoor tables, and took on staff to set up and tear down tables and chairs after each show.

“We felt like we were getting a little bit of a rhythm going mostly with local acts but a sprinkle of national acts and we had our procedures down, and toward the end, most of the shows were selling out,” Leddy says.

The same goes for The Grog.

“We were open for six shows and it was great!” Blackman says of the performances. “They all sold out and we had more bands who wanted to play. Then we got shut down again.”

Then the second wave hit, and it was back to closed doors. However, both venues have kept barebones staff.

Banding Together

At a time when it would be easy for it to be every outlet for itself, Cleveland’s independent venues are joining together in order to survive. Luckily, the city hasn’t had a stiff rivalry over turf. Cleveland’s music rooms have long been cooperative with one another and each wants the other to survive.

Each of the owners is respectful of the artists who play “across town,” as well as respecting each other’s histories with the artists. This makes it easy for them to get along and figure out how they’re going to survive collectively and create a strong sense of community. They discuss all this on a weekly call where the venue owners chat about a variety of survival topics, including booking information. The venues also joined forces along with two others to put out their own beer brand with each venue’s artwork decorating said can.

“I think that also has to do with the Midwestern perspective, too,” Zaleski says of the cooperativeness. “There’s kind of that helpfulness as well. You see that in the local record stores especially. Everyone has realized for the greater sake of the scene, and for the greater sake of musicians, it’s much better to band together and we’re stronger together than trying to operate apart.”

Music’s trickle-down effect

The hole in the concert calendar has impacted many outside of the venues and musicians. Photographer Janet Macoska has been a fixture in Cleveland’s scene for over four decades. Prior to the pandemic, she shot over 100 shows a year for Hard Rock Rocksino (now MGM Northfield Park) in nearby Northfield, and in 2017 was inducted into the Cleveland Journalism Hall of Fame.

Macoska’s photo archive is impressive. Shooting since 1974, she’s captured some of the biggest names in rock history who made their way through town, including David Bowie, Van Halen and Iggy Pop. You name ‘em, she’s photographed ‘em. When the music stopped in 2020, Macoska had to get creative. She already has an anthology of her photos that she’s been selling and she made a calendar as well, to, in her words, “keep my images alive and in front of people.”

Even so, Macoska is worried about how quickly large-scale live music events will return. Despite Live Nation’s rose-tinted view, she feels strongly, however, that “many, many people will stay away from large concert crowds or sports just because they are worried about being crammed together with a bunch of strangers.” Continuing, she doubts she’ll be quick to hop back into the photo pit and is planning to be careful when she takes on a gig. That’s tempered with an eagerness to get back to doing what she loves.

“Shooting photos of performances and musicians is the blood in my veins, my heart, my soul,” she says. “It was the most agony when COVID started. It doesn’t feel any better now, except that I can be creative, looking at my archive of work and scanning old negatives and color slides for upcoming projects…but nothing takes the place of doing the creative work I was put on this planet to do. The music, the visuals, the energy of live performance feeds my soul….and I miss this terribly.”

Is this it for independent venues?

These problems aren’t unique to Cleveland. Many of the major Midwestern cities that have independent music venues are facing the same uphill climb as The Grog and Beachland. As promoter powerhouses like Live Nation and AEG continue to gobble up venues, it leaves smaller ones vulnerable — especially now — and they could go away. And if those smaller places go away, fewer rising bands would be likely to tour the region.

Both venues have holds for 2022 already filling up their calendar. But with ever-shifting pandemic regulations, things can change quickly. For now, both venues are cautiously optimistic that as the vaccine continues to roll out, things will happen sooner than that. And in Ohio, it seems like help is on the way.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine has earmarked up to $30,000 for bars, restaurants, museums and clubs like The Grog and Beachland, which would be a tremendous boost. As would funds raised by the National Independent Venues Association [NIVA]. The organization raised nearly $3 million last year through its #SaveOurStages campaign and successfully lobbied to get relief for independent venues included in the stimulus bill passed in December. It offers hope, but the venues are fighting for aid alongside museums and other arts venues.

“Cleveland’s got the attitude that you can still make things happen,” Baldi says. “Even if you’re faced with a crushing reality, there’s plenty of ways to try to keep music going. I think there’s enough grit to power through what they’ve been through.”

Leave a comment