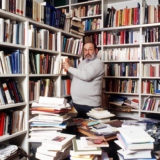

The celebrated Italian intellectual, Umberto Eco, died five years ago today. During his time, he was the preeminent expert in the field of semiotics, the study and interpretation of signs and symbols, lecturing at numerous universities. He was also a prolific writer, penning seven novels, over 40 nonfiction works, and even three children’s books.

He is best known for his extremely erudite and theory-intensive novels The Name of the Rose and Foucault’s Pendulum. Foucault’s Pendulum is his postmodern magnum opus full of esoteric allusions to secret societies, pseudoscientific sects, and other medieval arcana. The encyclopedic novel is a fat pill to swallow and its reward is simply coming out the other side of it. It is a test of one’s will. Anthony Burgess (author of A Clockwork Orange) says the novel is “crammed not with action but with information” and quipped that it “needs an index” and that “forests have been chopped down to print it” in his New York Times review.

Eco’s other highly allusive (and elusive) 500-page phonebook of a debut novel, The Name of the Rose, was a bestselling whodunit novel riddled with semiotics and medieval theology (like Foucault’s Pendulum) selling over 50 million copies and making it one of the highest bestselling novels of all time despite its abstruseness. But, Eco infused his beloved scholarship into his creative works, requiring the reader to decode the signs Eco intentionally implanted within them.

You wouldn’t be wrong to conjecture that even his very name seems to be coded. He inherited it from his grandfather who was a foundling at the time city hall officials were elected to name forsaken children. So, the abandoned boy that was his grandfather was christened “Eco,” an acronym for “ex caelis oblatus” meaning “given by the heavens” in Latin. In a display of his patent cynicism, he supposed it was “better given by the heavens than by hell.”

Eco wasn’t just a world-famous novelist slash professor gracing the earth with his brilliance, he was also somewhat of a pop cultural star, whether the mainstream knew it or not. In a famous lecture, he coined the term “semiological guerilla” – the concept of undermining the dominative mainstream mass media’s control over the system of language; published an essay about America’s obsession with simulacra and counterfeit reality, going for the jugular on popular Americana miscellanies like wax museums, Superman, holography, and the implications of tight jeans; and even had a cameo in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film, La Notte, on the set of the publishing house at which he worked as a well-known editor.

His achievements seemed without end, even for a consecrated man. But like all other aged mortals, his end loomed. He developed and suffered from pancreatic cancer for about two years until he finally checked out of this world for the next.

Or should I say, was taken back?

Leave a comment