On a stage draped with pieces of gauzy white fabric, Cate Le Bon enters to a mesmerizing wall of sound. Like the rest of her band, she is dressed in white, and swaying behind the microphone as she begins a song called “Jerome.”

Her voice rises softly from the swirling, surreal music, with lyrics grappling with the end of something meaningful: “Gently read my name / Cry and find me here / I’m eating rocks / And so it goes Jerome, Jerome / There is nothing you can hope for.”

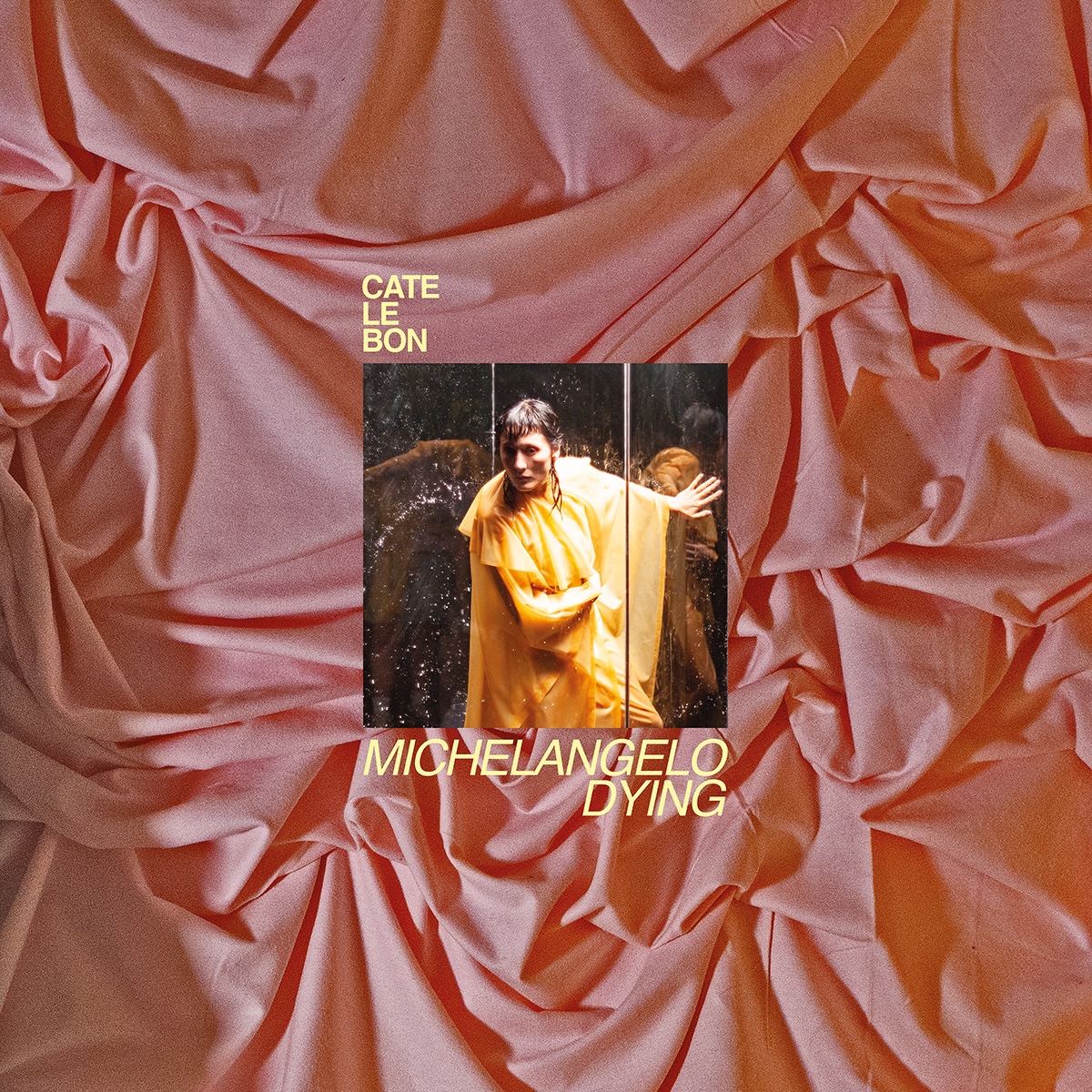

The song is also the opening to her new album, Michelangelo Dying, an especially personal work written and recorded after Le Bon’s breakup with a longtime romantic partner and sometime collaborator. On this night, January 31, the Welsh singer, multi-instrumentalist, and producer performs most of the record to a full house at the century-old Belasco Theater in downtown Los Angeles, marking the final date of her world tour.

While her seventh solo album is at the center of her show, she also brings out her friend St. Vincent to perform their new single, “Always the Same,” an understated song of devotion recorded during sessions for Michelangelo Dying. Like the album, the song is not about venting but exploring through the fog of emotion and memory. During the tour, Le Bon has noticed a few fans in tears as the songs unfurled.

A week after the concert and its hazy, dreamlike glow, Le Bon is still in L.A., a city she once called home. She sits by the window of a coffeehouse in Los Feliz, clad in a black long-sleeved shirt, sunglasses resting atop her short blonde hair, cheerfully sipping green tea.

“I didn’t want to write a record about heartbreak, because of the danger of it being cliched,” she says of Michelangelo Dying. “It is about heartbreak, but it’s mostly about me experiencing heartache rather than it being directly a narrative about something that happens.”

She’s not interested in unveiling the true stories behind the songs, yet most reviews note that the album follows her breakup with American singer-songwriter Tim Presley, with whom she collaborated on the project Drinks. By then, she had lived in Los Angeles and then the nearby desert landscape of Joshua Tree for several years, but returned to her native Cardiff, Wales, after leaving the relationship.

A habitual writer and diarist, she began turning her experiences and feelings into songs. On the album’s swirling, painfully rhapsodic “Is It Worth It? (Happy Birthday),” the words are raw: “I make jealous talk / I break my heart / Make a joke of love / And of living.”

“It’s about experiencing the kind of the turbulence of what happens afterwards, and how do you put it down so you can move on?” she says. “It feels a little abstract, but even if I didn’t understand fully what I was writing in the moment, I knew it was real.”

Her lyrics unfold within a warm sonic fabric, with lush arrangements that favor mood and texture over sharp edges. Her work is usually called indie rock and avant-pop, but the music is both modern and out of time, as fitting in the current vanguard as she would have been in earlier generations of what was once vaguely called art rock.

“I felt like a lot of the emotional information was in the arrangements,” Le Bon explains. “I’d spend days just working on a bassline that fit around the guitar line that fit around the synth line and everything had to speak to each other. It’s very all woven together. There’s a mesh to it. There’s no lead instrument. You take one thing away and it falls apart.”

Later this afternoon, Le Bon will be helping a friend mix some songs, and before leaving town she hopes to work on new music with her friend Stella Mozgawa, drummer of Warpaint. “I’m keen to work on something,” she says. “Whether it’s the beginnings of a new record or a collaboration. I want to get my teeth into something.”

Aside from her acclaimed work as an artist, Le Bon has become an in-demand producer in recent years. She has guided albums by Wilco, Deerhunter, Devendra Banhart, Horsegirl, Kurt Vile, and most recently, Dry Cleaning. It is an almost accidental avocation, which accelerated after she left L.A., and bounced to and from studios around the world.

“It’s something I love doing, but I don’t want to be a producer,” she says. “I like making my own music. Then when someone I love, and I feel a kind of chemistry or a nice friction with, asks me to work on a record, it’s a no brainer. I’m excited about it.

“It’s such a nebulous kind of job,” she goes on. “Each artist or band demands something different from you. That’s why it’s important to not have a repeatable process, so that you can respond to what’s needed from you. That’s only possible when you don’t do it frequently.”

In some ways, Le Bon’s career has mirrored that of her elder Welsh compatriot, John Cale—formerly of the Velvet Underground—who released some of his best solo work during the same years he produced groundbreaking records by Patti Smith and the Modern Lovers. Cale appears on Le Bon’s new album, harmonizing on the elegiac “Ride,” but their connection goes back further.

In 2017, Le Bon took a year off from music to explore a new obsession: furniture making. She spent that year in England studying design and construction at the intensive Waters & Acland furniture school. At the very end of her time there, she received an unexpected email from Cale, inviting her to sing with him at London’s Barbican Centre.

“I just remember I was crying at my work bench, which isn’t nothing. That doesn’t happen,” she says.

At the performance, billed as a “Futurespective” look at Cale’s five-decade career, she sang and played guitar on the songs “Buffalo Ballet” and “Amsterdam.” They reconvened in Paris soon after, ultimately spending weeks in rehearsals, deepening their musical and cultural connections. “He always speaks a bit of Welsh to me,” she says with a smile. “I love him and his work so much.”

“There’s always been something about his attitude towards it all: You can have a career that is bigger than the thing you’re making,” she goes on. “There’s an overview, but it’s also forward motion.”

Le Bon has another special relationship with Annie Clark, aka St. Vincent. The single “Always the Same” is only the latest in a series of collaborations between the artists. Le Bon sings on the title track of St. Vincent’s ambitious All Born Screaming, she co-wrote the song “Big Time Nothing,” and plays bass on two tracks. Le Bon doesn’t see a direct link between the two captivating albums other than their bond as friends and artists.

“They’re emotionally very different records,” she says. “My record is so insular and it’s like an echo chamber of itself, informing itself in different ways as it happened. But I feel a really deep creative connection with Annie.”

“We’re really honest with each other and really supportive, admire each other’s work,” she adds. “I really respect how she questions things in a way that is uncomfortable sometimes, which I think is important, but the questioning is always restorative. It’s never reductive. You have these really unexpected conversations with it that are confronting, but there’s a value to that. Whether that’s creatively or whether that’s as a friend, there’s growth in all of that. It’s nourishing.”

Le Bon has similarly deep creative and personal conversations with Australian singer and songwriter Courtney Barnett and Mozgawa. “We talk about this stuff and the emotional side of making music,” she adds. “They’re all present, whether they’re on the record or not.”

Her newest music is always front of mind, she says. At the Belasco, Le Bon’s set was mostly from Michelangelo Dying, but other songs from her past continue to resonate. She showed her flintier side on “Mother’s Mother’s Magazines,” a song from 2019’s Reward. From the same album, she sang “Daylight Matters,” patting her chest like a heartbeat, slowly swaying behind the microphone.

“I don’t like playing songs that I don’t feel a connection to anymore,” Le Bon says. “I just like forward motion. I’m mostly excited about the stuff that I’ve just done, and I feel connected to it. In the world of performance, that’s real to me.”

The songs of Michelangelo Dying were created, she says, “when I was in a lot of pain. They helped me heal. Looking back on them, and being able to sing them from a very different place, was hugely rewarding in many ways.”

Leave a comment