Mike Scott of the Waterboys doesn’t like to use the word “obsession” to describe his particular affliction. When it comes to the creative artists who have moved him over the decades, he prefers to identify as a “completist,” as if he was a humble archivist, a cultural trainspotter observing the minutiae of his favorite musicians, filmmakers, and poets from a safe and impartial distance.

Whatever the designation, he first embraced his heroes with a passion as a teenager in Ayr, Scotland, exploring the groundbreaking work of the Clash, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, and many others in the pages of his photocopied fanzine, Jungleland. The intense study and excitement he experienced as a young punk rocker would ultimately inspire his own deeply felt work leading the Waterboys since 1983.

He’d been the kind of fan to travel far from his home to witness these artists in action and speak with them, while devouring every B-side and bootleg, and every available concert setlist.

“I enjoy it and have that kind of mind. I’d always pour over Bruce’s setlist, Bob’s setlist, fascinated by the tiny changes,” Scott says now, comparing this close study to a sports fan looking over stats and player selections from a team’s winning year. “It’s fascinating, the changes and the mind that’s making the changes—Bob’s mind as he moves from gig to gig, and Bruce’s mind. Why does he change that? Why does that song disappear?”

Scott is recalling all this over an espresso the morning after performing a concert in Los Angeles. He’s in a quiet coffee bar in the lobby of his downtown hotel, and a van is waiting at the curb to take him and the band south to a record store appearance in Long Beach, and then another live show in San Diego later this evening.

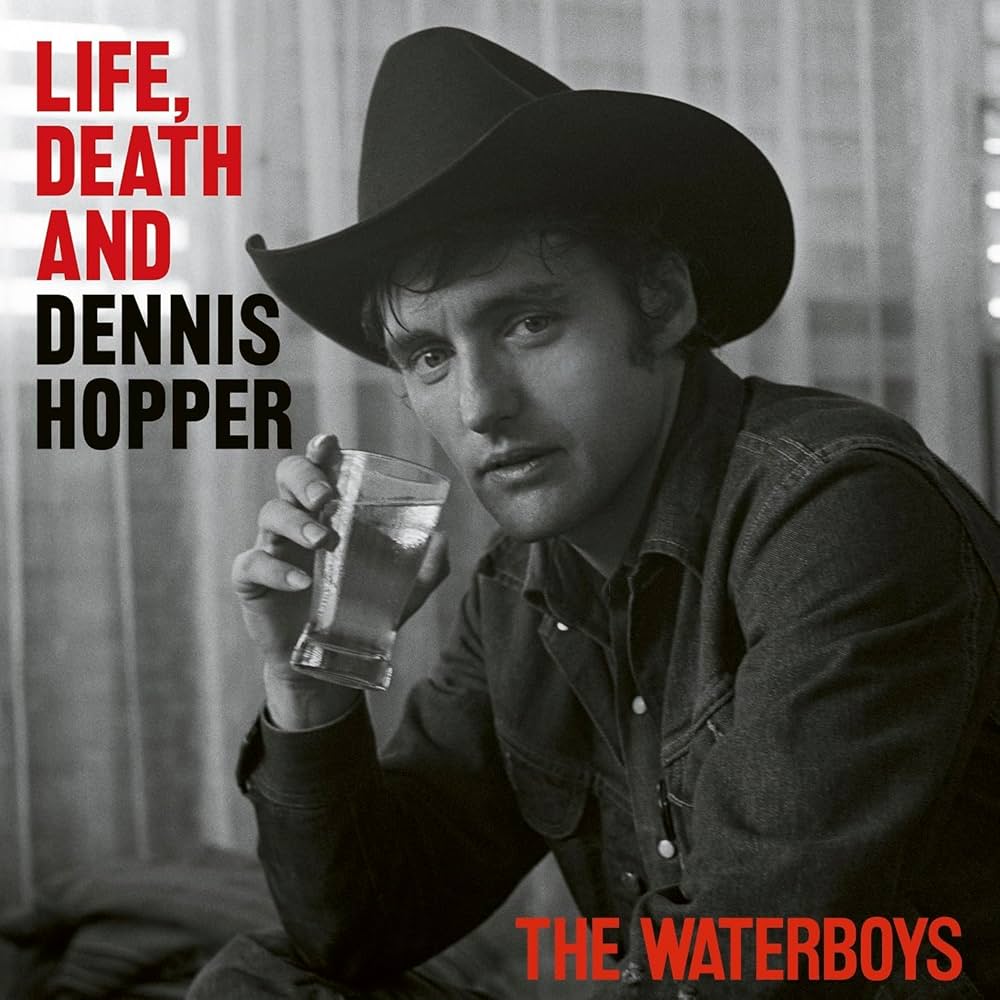

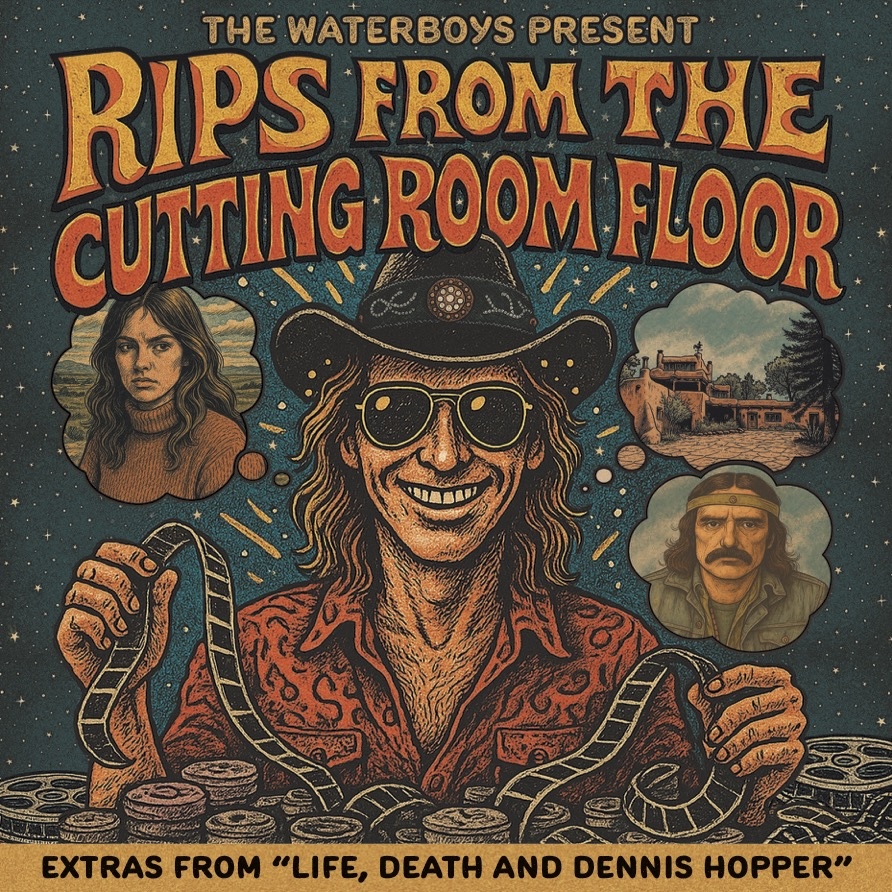

It’s the final days of his North American tour in support of the new Waterboys album, Life, Death and Dennis Hopper, the band’s 16th release. In many ways, it represents a grown-up version of the same impulse to fully explore the life and work of an artist, an album-length musical biography of the actor-director-photographer Dennis Hopper. And if the 25-song album wasn’t enough to satisfy a Hopper fan, a collection of outtakes is set for release in December: Rips From the Cutting Room Floor.

While obviously familiar with Hopper as a counterculture figure and actor known for searing later career performances in Apocalypse Now and Blue Velvet, Scott was newly intrigued several years ago at a London gallery when, for the first time, he saw Hopper’s work as a photographer. The black-and-white pictures from the 1960s captured actors and musicians, painters and bikers, and abstract scenes from the evolving streets of Los Angeles.

“I was blown away,” says Scott, who bought a couple of biographies and went deep into Hopper’s history. “It was a doorway into Dennis’s world, Dennis’s personality, Dennis’s soul. And that got me interested in him as a person, and as a traveler.”

At 66, Scott is old enough to have childhood memories of the 1960s. “I remember my mother saying to me, ‘The flower people are coming,’” he says with a laugh, recalling the great pop singles he heard as a young boy in 1967.

From the beginning, the Waterboys leader’s work has drawn its share of obsessives and completists for music dependably passionate and sweeping, aiming to capture the fullness of life. It was part of an ’80s movement of ambitious new rock music named after a song called “The Big Music,” from the Waterboys’ 1984 album A Pagan Place. Others linked to that scene included U2, the Alarm and Big Country, among others.

This Is the Sea from 1985 was an early triumph, including the fan favorites “Don’t Bang the Drum,” “The Whole of the Moon,” and the album’s title song. As frontman, Scott might have assumed a kind of messianic rock persona to match the sound, in the Bono mold, but chose to let his music do the talking, he says. “I don’t think I was like that. Too shy, really. Spiky, maybe,” he adds, reflecting on that era. “I’m not demonstrative and gesture-full like that at all. It’s not me. And I never really thought our music was like that. That ‘Big Music’ term comes from a song I wrote, which was a metaphor.”

The band followed up with a shift in direction, on the Irish folk-flavored Fisherman’s Blues, just one early sign of the restlessness that would guide Scott in his later career, as he explored multiple styles, from funk and soul to blues and electro-rock.

“It’s conscious, but it’s not deliberate,” explains Scott, who has lived in Ireland since the mid-’80s. “I like to keep things fresh. I like to interest myself, and I’ll get bored if I repeat things. I get interested in something new and I want to go there.”

The Hopper album takes that idea even further, with songs untethered to any single style, each track guided only by an event or period being explored in Hopper’s life story. So the music travels from country-folk and effervescent jazz to noisy rock and dreamy balladry.

Five years after seeing Hopper’s photographs, Scott wrote a song called “Dennis Hopper,” which appeared on the 2020 album Good Luck, Seeker. “It was a fun song, because all the lines rhyme with ‘Hopper,’” he says now with a grin. But it was hardly enough to satisfy his growing fixation, and during the pandemic he thought about expanding that to a digital EP, and started writing more Hopper-themed music, as did Waterboys keyboardist Paul Brown.

“We had four pieces. Then one thing led to another and then it was six pieces, 10 pieces, 12 pieces,” Scott says. “I realized it’s an album and it’s his life story, and why not?”

Writing and recording an album as a biography was different from anything he’d attempted before. A record that set music to the poetry of William Butler Yeats was as close as he’d come. And there was the occasional song inspired by a real person, like 1983’s “A Girl Named Johnny,” about Patti Smith.

The Waterboys’ Hopper album is not just about the actor, but the whole swirling culture that he was a part of—starting with his escape from his Kansas birthplace to early acting roles with his friend James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause and Giant in the 1950s. By the 1960s, Hopper was an early collector of pop art, and then came his sudden rise amid a new generation of filmmakers as the director of Easy Rider, followed by years of dramatic ups and downs, acclaim and crises, until his death from prostate cancer in 2010.

“Very few artists have had such a meteoric rise as he did with Easy Rider, and then the complete opposite with the next film, the complete collapse of his cache and his standing. It was a wild ride he had,” Scott says, pointing to the filmmaker’s “personality and his character and the risks he took, his bullheadedness, his maverick qualities and his dedication to art. Dennis is a singular character.”

For Hopper, movie-making could be unpredictable. In 1969, he appeared onscreen with establishment icon John Wayne in True Grit exactly one month before Hopper became a major counterculture figure with the release of Easy Rider, acclaimed both as the auteur behind the camera and for his wired on-screen role as one of its two antiheroes riding cross-country on low-slung choppers.

“He was a jobbing actor,” says Scott. “He was part-auteur, but it never quite worked out for him in a sustained way. He never had the run of five movies that he directed and starred in. That’s what he really deserved.”

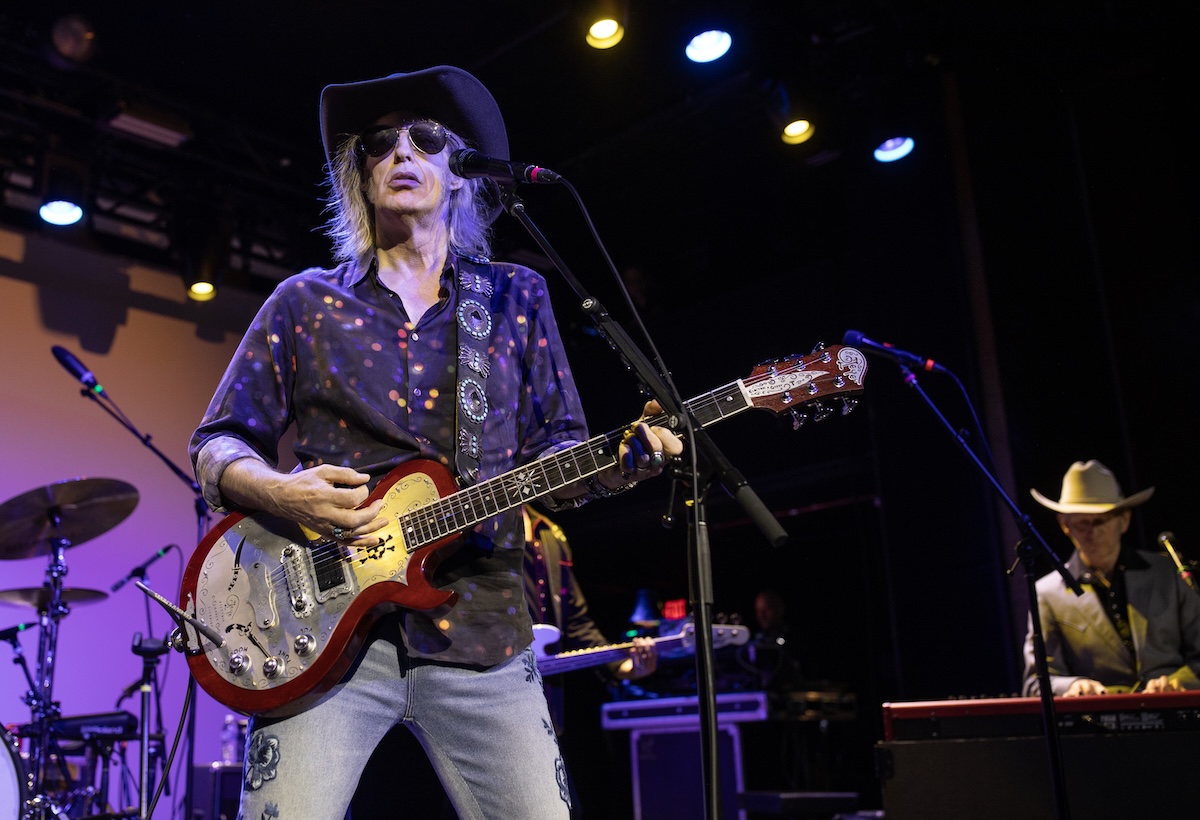

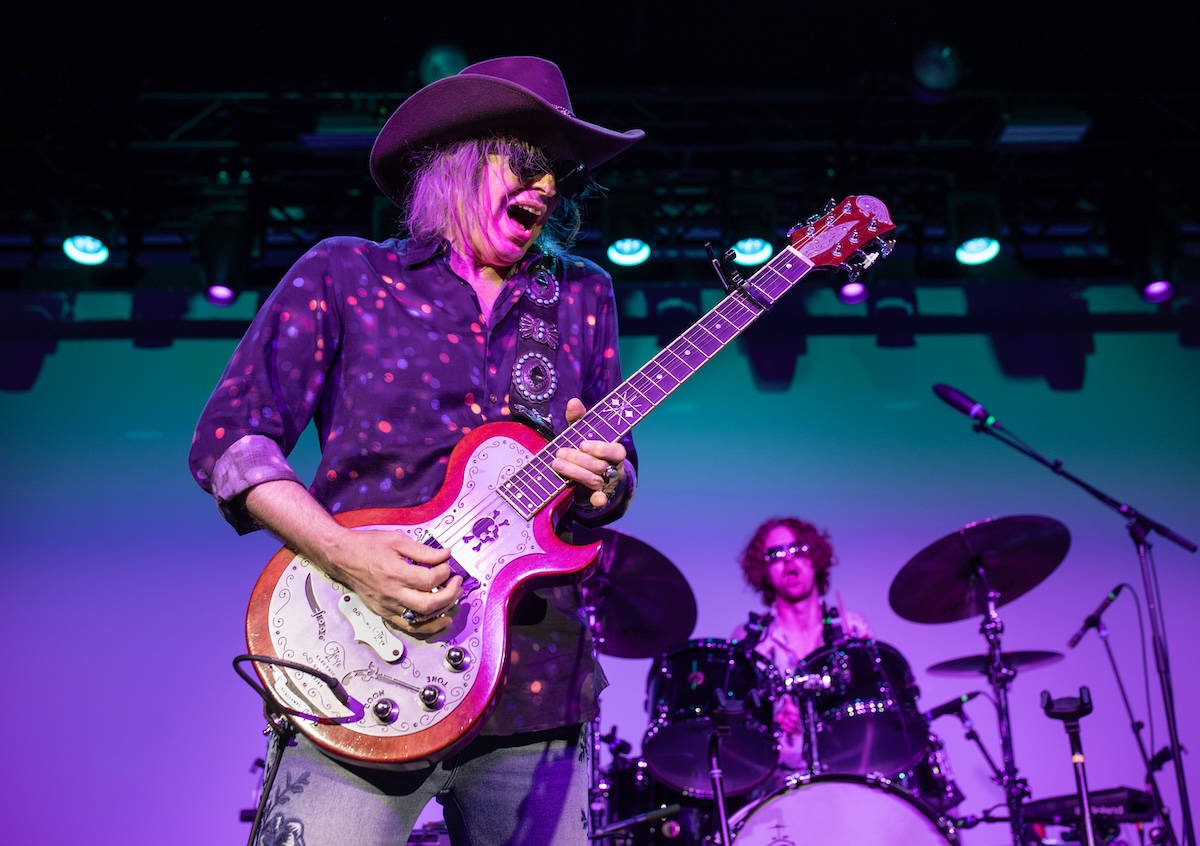

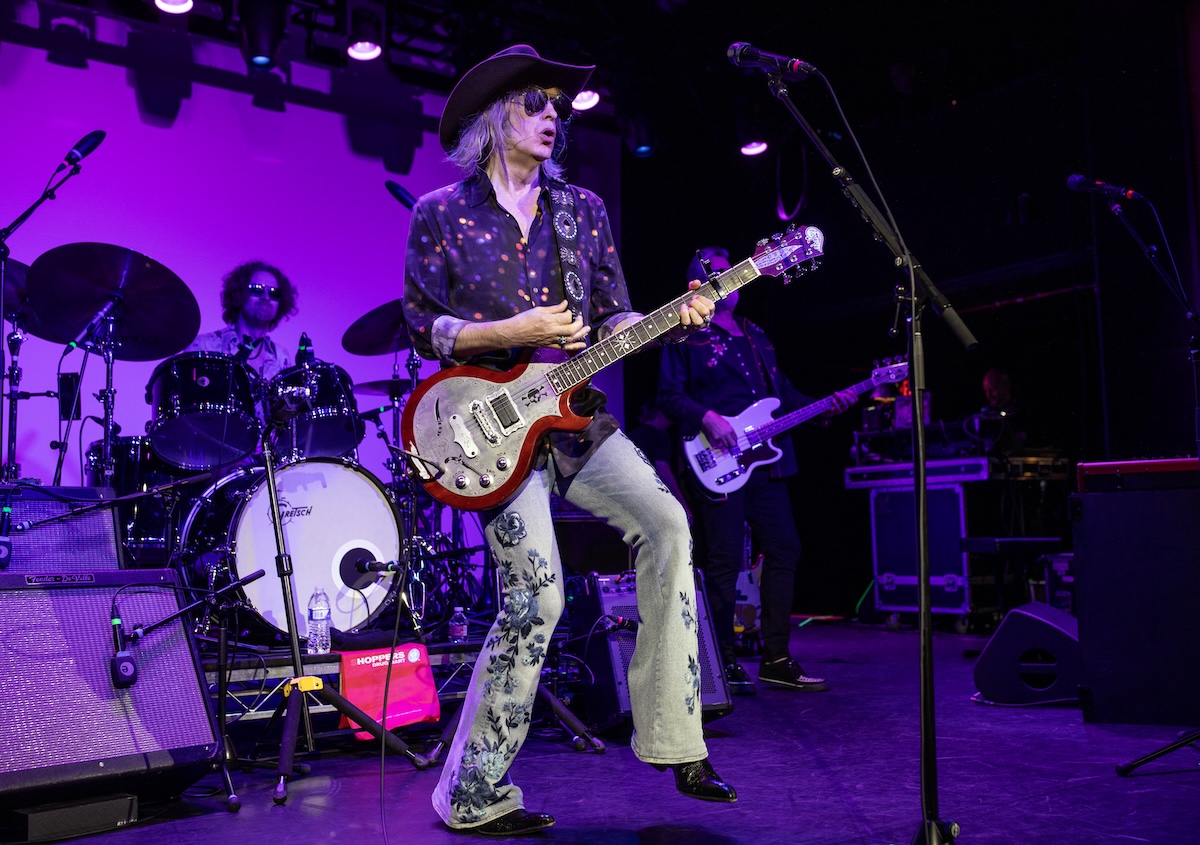

As he sits in the coffee bar, Scott is wearing the same cowboy hat he had onstage the night before. Combined with a blue Western shirt smothered with white stars on his shoulders, it represents a very different image of Scott from the early Waterboys, when he dressed more like a Celtic rock poet, but it fits well with his current Hopper theme.

Bringing the tour to Los Angeles carried extra weight for him. “L.A. is a Dennis Hopper town, so it was very important to me to bring the Dennis Hopper music here,” Scott says. “There’s an edge in LA. It’s hard to describe what it is, but there’s an entertainment industry, glamour industry, dream factory-type edge to Los Angeles that I like playing in to.”

The last song recorded for the album was “The Tourist,” which lands like a collaboration between the Beach Boys and Buffalo Springfield that never happened. It opens with angelic vocal harmonies that could be Brian Wilson and the boys, followed by heavier rock guitars that echo Stephen Stills and Neil Young. The track was recorded in an analog studio in London to help recreate the texture of the era, and Scott made a playlist for his rhythm section of Buffalo Springfield and Jefferson Airplane songs “so they could bone up.”

Onstage at the Bellwether in Los Angeles, you could see Scott preparing himself for the song’s big rock guitar solo, planting his feet and getting his fingers in position. “I look forward to it all through the show,” he says happily.

The album’s opening song, “Kansas,” is sung by Steve Earle, the first of several notable guest vocals, and an indication of real respect for Scott from his peers. Scott cast his co-stars like a movie.

For the smoldering “Ten Years Gone,” he recruited Springsteen to help explore a long stretch when Hopper’s life and career had again run aground. Springsteen recites dramatically: “Somewhere out there beyond the limits, man, there’s a story being told, a movie being made and he’s in it, man. He’s still moving, he’s still grooving, he’s still able somehow to bring some of that old magic to the table.”

Ask Scott about Springsteen’s similar spoken-word cameo on the 11-minute title track to Lou Reed’s 1978 album Street Hassle, and he immediately recites the Boss’s improvised closing line: “Tramps like us, we were born to pay.”

“He was good on that. It’s a similar deployment of his skills,” says Scott, who finally met Springsteen in 2012 at a Waterboys show in Dublin. “I asked him to do this one because I loved the stories he would tell onstage and his dramatic delivery, the tone of voice. It’s got gravity.”

Also on Hopper is Fiona Apple, who delivers a weary, agonized performance on the bleak “Letter From An Unknown Girlfriend.” With a focus on the domestic violence in Hopper’s life, the track is just Apple’s piano and vocal, as the song begins: “I used to say / No man would ever strike me / And no man ever did / ’Til I met you … Sweet you.”

Apple sent Scott a demo of her take, and as with Earle’s opening track, the Waterboys leader heard something startling and real in her barebones recording and used it on the album. “I very much felt that the record needed a female voice,” he says. “And I wanted to give the women in Dennis’s life a say.”

In 2019, Apple recorded an especially visceral take on the Waterboys’ “Whole of the Moon,” biting hard on the lyrics as if they were her own, and got Scott’s attention. “That was the trigger for me,” Scott recalls. “I loved what she did with it. She brought such emotion to it.”

Near the end of Hopper is “Venice, California (Victoria) / The Passing of Hopper,” equal parts traditional “Taps” bugle call and Ennio Morricone.

On Rips, the upcoming collection of Hopper outtakes, is “Western Roll Call,” as Scott playfully growls a list of character names played by Hopper in Western films and television, from the famous (Doc Holliday, Billy the Kid, etc.) to the obscure and made up (the Ohio Kid, Jimmy Sweetwater, among them) to a hip-hop beat. The song comes with an AI-generated music video that brings to life in comic book form 19 different cowboys Hopper played. There is also a song about Hopper’s interactions with Elvis Presley, “The Next Time I Saw Elvis,” and a forlorn song of defiance, “Still Raging On.”

As he prepares to bring his Hopper tour to Europe, Scott sees his exploration of the culture that has moved him since childhood as open-ended. He’s witnessed a lot of it, from ’60s rock to punk and beyond.

“I feel that I’m lucky to have been a kid and a young person during a golden age, about half of it as a conscious person,” Scott says. “I’m very grateful for that. It’s still that period that inspires me most. I carry part of that energy in me. It’s in my DNA.”

Leave a comment