On May 21, 1998, I saw Garbage at what used to be The Palace in Hollywood. I wasn’t there for Garbage—I came for the opener, bizarrely, Talvin Singh—but I left singing Garbage songs. I knew all the singles. How could you not in the ’90s, when their music was everywhere?

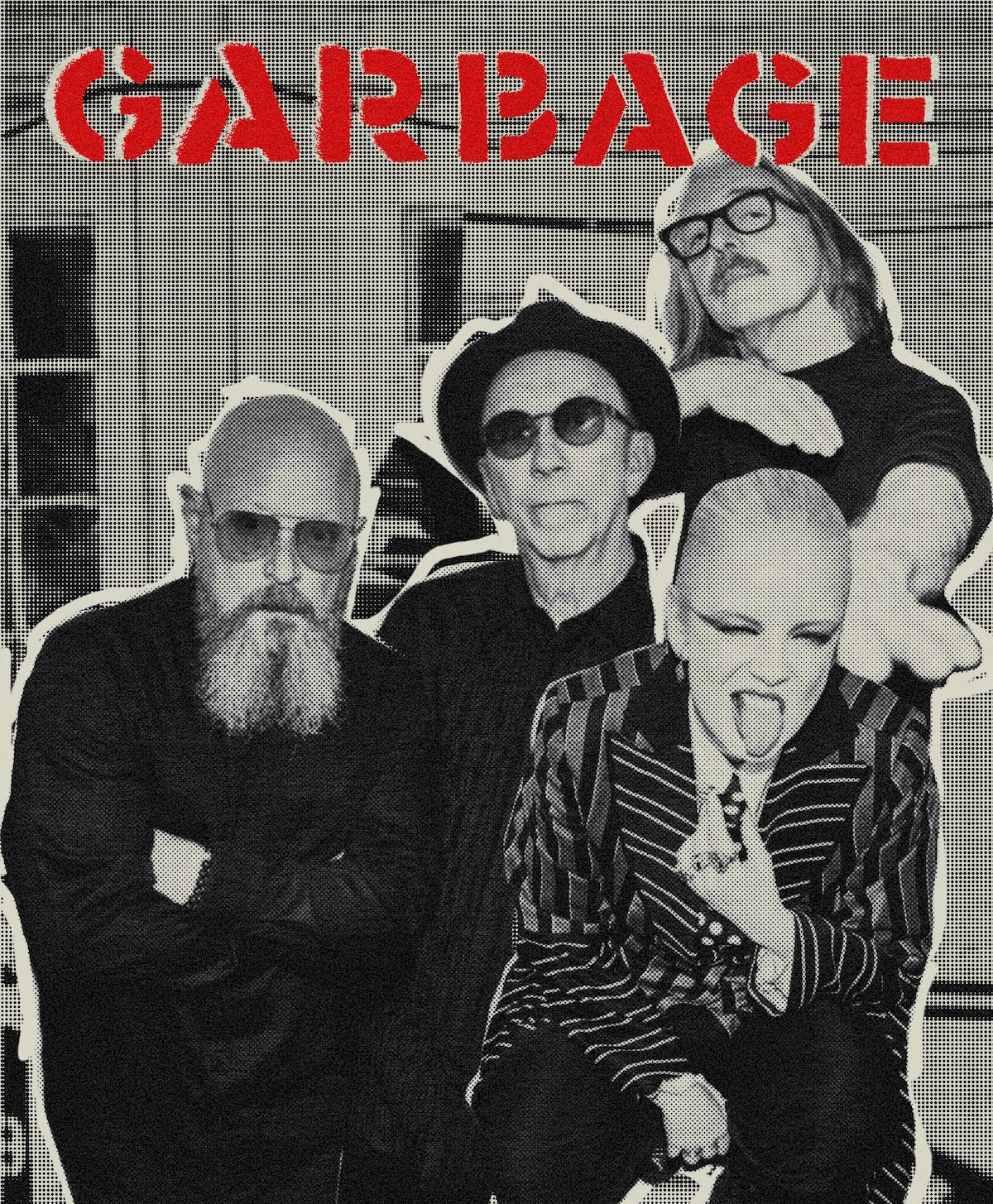

Even more than the songs was the impact of frontperson Shirley Manson. In a miniskirt, baby T, and tall boots, all black from neck to toe, she looked amazing, aspirational—and we loved her. Twenty-four years later, opening for Tears for Fears, she was even more compelling: theatrical, like a Disney live-action villain, taking up the whole stage.

Offstage, Manson is equally commanding, confident, and opinionated. Our hour-plus conversation is punctuated with her throaty laugh. One of the many qualities that makes me want to grow up to be her.

Garbage’s eighth album, Let All That We Imagine Be the Light, came out earlier this year, and on September 3 they begin the extended Happy Endings Tour in support of it. This time, the album creation process was unlike any before. In 2024, Manson was literally knocked off her feet by a performance-related injury, undergoing hip surgery and a painful recovery—followed by another surgery.

The writing and recording of Let All That We Imagine Be the Light was bookended by these surgeries, with Manson physically separated from bandmates Butch Vig, Duke Erikson, and Steve Marker. This unusual setup—plus some pain meds (she namechecks Tramadol in the album’s closer)—produced some of her sharpest lyrics yet.

The album has earned thoughtful press, and with her quick, clever answers to both mundane and incisive questions, Manson is effortlessly quotable. Her arsenal of words: “desolate,” “ludicrous,” “tiresome,” makes me want to steal them for my own speech. Sirens and helicopters monitoring DTLA’s unrest underscore our talk, but her points land without interruption.

Was it more, or less freeing working apart from your bandmates?

It was ultimately quite freeing for me—although I definitely wouldn’t want to make another record the way we made this one because it was very alienating for me. But it forced the band to write differently and as a result, the record sounds different. It’s much more cinematic, and I don’t know if we would have necessarily gotten there had we all been in the room together. Without vocals, without any melody to follow, you have to rely upon the music. In a way, it pushes the emphasis on that.

When the band started sending me pieces of music, I was quite taken aback. I wasn’t 100% sure how to delve into it. Initially, I was a bit thrown off by it. One of the songs in particular, I remember turning to my husband and going, “What the fuck am I supposed to do with this?” That ended up turning into “The Day That I Met God,” which is one of the songs that I love the most, and is such a departure from our usual sort of songwriting style.

Isn’t that what you always hope for 30 years into a creative endeavor, to stumble upon something that feels fresh to you? That’s really quite thrilling for us.

“The Day That I Met God” is my favorite on the album—and I’m allergic to Tramadol.

Everybody has responded surprisingly well to that song. I honestly thought people would be like, “What? Huh? Where did this come from?” But the music is quite euphoric with really beautiful chords and it inspired, I would argue, the best chorus of our career. It’s uplifting and really loving and kind. Maybe that’s why people have responded to it so well.

Tramadol is a powerful drug. I threw it in there to be a little wry. To try and describe what God is to you, that’s a large, heavy topic. When I first came up with this chorus, I was on the treadmill, and I was singing it to myself without music. I went into my bedroom and recorded it. When I got to the chorus, I realized I’d hit on something truthful and moving for myself, and it gave me goosebumps. I was fully aware that I was medicated, so I threw the Tramadol part in there, just for fun. But I think it adds a certain gravitas to it too. I thought it’d just be a space saver, but I ended up holding on to it.

Is the album connected to your physical pain?

It was quite a difficult period for me because I required hip surgery at the beginning of making this record, and then I needed another hip surgery on the opposite hip at the end of making this record. I was basically in pain, or struggling to control my pain. That was wild because I was dealing with a lot of brain fog. I was physically depressed, obviously, and became somewhat emotionally depressed. The writing of this record is colored by that.

I’ve never been in pain my whole life, which is why it was so shocking to me. I’ll be 60 next year, and I have never broken a limb. I have never had serious surgery. I was such a virgin to the whole process. It changed the way I look at people living with chronic pain. It’s such a torture. Making this record felt like a period of exaggerated growth. I had to learn things about myself, about the world, that I never had to consider before. I’m grateful for that experience, but in the end, even though it was far from fun and extremely unglamorous, I’ve never felt more beaten down in my life, but also, I learned so much.

What were some positives you came away with after going through your physical challenges?

There were a lot of positives. It was really good for me to create by myself, without anyone in the room, which arguably I’ve never really done since probably the first record. Usually everything Garbage does, we’re all together in a room, and fumble through until we find something to grasp that we can all agree on. I had to be the sole decider of whether I thought something was good enough to take to the group. That’s good for the creative process where you’re being the architect, essentially, of your own work. I’ve been in a band with Butch my whole career. Over the years, especially very early on, I depended on his blessing that I’d done a good job. As you grow as an artist, you need less confirmation from other people, and you rely on yourself. That’s a fantastic feeling. It’s really liberating.

When you’re going through physical rehab and learning how to walk again, you have to focus on tiny increments of improvement. That taught me the value of effort and discipline and small strokes as opposed to large, big splashes. I’m such a big personality, and I’ve relied on broad strokes my whole life. This experience has taught me how to focus on the smaller moments and the smaller advances and smaller gestures, that I’m grateful for. That’s been a profound lesson for me in all of this.

Is there a connection between this album and its predecessor, No Gods No Masters?

They do sit together side by side as non-identical twins. On No Gods No Masters, I was very frightened about where I feared the world was headed. You can be outraged or furious about the things that you’re frightened about. No Gods No Masters was quite a political record. It was me tolling a bell of warning. Five years later, I realized there’s no point. There’s no use for my outrage. It’s too late. We’re exactly where I imagined we would end up as a global community, and my outrage was not going to be of any help to anyone, least of all myself.

I realized I had to employ a completely different tack. I had to come at making a record from an entirely different perspective to ensure my own sanity. The world had become so extreme and chaotic and cruel that I wanted to engage with this idea that I was able to infuse my work with love and kindness. It sounds like such an embarrassing cliche, but it’s true. The only thing within my power was to shout and scream and rage and rant, but I already tried that with No Gods No Masters. Nobody listened to what I thought was very clear messaging on that record. So I felt I had to put out into the world the spirit I wanted to see in the world. You know: “Be the change you want to see in the world.” Anything I put out into the world from now on has to be dripping with love. It has to be dripping with kindness. That’s a monumental shift in my thinking. I’ve never thought along those lines before.

When I was young, I was contemptuous of love, I made the mistake of thinking that love was some kind of cheesy Hallmark card. As I’ve gotten older and more challenged by circumstance, lost more friends, seen my friends bury their children, I’ve started to become aware of all the different kinds of love, all the different facets of love that exist in the world that I’m able to tap into, and the least of all of that is romantic love. Romantic love is important and wonderful if you’re lucky enough to enjoy it. But so too is the love of your community, the love of nature, the love of animals, the love of your neighbors, your band, the list is endless. I found that very helpful, a spur for me whilst making this record at a time when I was physically and emotionally depressed.

Were mental health issues considered a sign of weakness previously?

Oh, god, yeah. I grew up in the ’70s, and nobody ever talked about mental health, ever. When I first moved to America, I didn’t believe in therapy or psychiatrists or any of that stuff. It was like a foreign language to me, because it hadn’t been part of my upbringing at all. Then I got to Los Angeles, and everybody had a therapist. I was really shocked. As I’ve gotten older, I realize I actually think it’s fantastic that we have developed language surrounding mental health issues. Some of the stigma has been removed from our culture, which is fantastic too.

We all have to be a little careful that we don’t put too much weight on normal levels of sadness, or completely negate the natural fluctuations of the human mind. We have to be careful that we don’t assume that means we are mentally unhealthy. It’s part of a healthy mind to have moments of deep sadness or depression or anger. Negative emotions are necessary and of vital importance to our wellbeing as human beings. If you’re constantly in a state of perpetual happiness, there’s something very wrong.

It’s natural for the mind to wander and flirt with dark ideas and dark thoughts. It’s part of being human and part of helping us understand others and helping us prepare for the inevitable challenges that occur in every lifetime. Nobody is going to be born and die and in between have nothing but great experiences. That’s just ludicrous.

Obviously, extreme depression, that’s something that needs to be medicated. But if you’re just feeling a bit down for a couple of days, there’s nothing wrong with that at all.

Where you are now gives a very different perception of you from early Garbage days.

When I emerged in the ’90s, I was painted by the media in such a way that I did not recognize myself—particularly the British music papers. The way I was spoken about was astounding. I feel like I’ve been trapped in that characterization for my whole career. This happens to a lot of women in the music industry. We get characterized and shoved into these little boxes, and we’re never allowed to escape them. I don’t identify with who I was in the ’90s at all, and I’m absolutely uninterested in being that person.

It’s frustrating to be an artist for 30 years—longer because I was an artist before Garbage. I’ve been in bands for 40 years. To be stuck in this role that has been assigned to me, I find it very frustrating and tiresome. Nothing I can do about it. I just have to keep making music, be a writer, be a creative. Every now and again I get lucky enough to talk to an amazing journalist who’s willing to let me redefine myself.

From what I understand, it sounds like you have a great support group in “The Coven.”

[The Coven] are a bunch of women who make music and have been very successful at it, and we share a certain life experience that nobody else we know has. We shoulder certain responsibilities and expectations and disappointments that are our common experiences that bind us to one another. We have provided a lot of comfort and support to one another, in an industry that is so unkind to all artists, but particularly to women,

It feels like that for women in the media as well. There is no room for aging.

That is a message broadcast in our society to women to disempower them entirely. Society fears an empowered woman. As women who are past the point of enthralling the male gaze, you’re free to start learning about the world you engage with. I don’t think we’re stupid to think that we might be punished for our age. I think women are continually “punished” for aging in ways that our male contemporaries are not.

The membrane that we imagine exists between our youth and our middle age is paper thin. If women accept their power and accept the fact that they are not objects, they are not things to be looked at, they are not things to be fucked and things to be admired and fetishized, once women accept that’s not their role, you can then accept your power as a human being on Earth.

If you’re not looking for praise for the way you look or your ability, then those things cease to be powerful. They cease to be relevant. The freedom that allows in your thinking and your existence on Earth is astounding, because you’re no longer looking for affirmation. You’re no longer looking for permission. You’re no longer being obedient. You’re no longer keeping yourself small. You can start to spread, take up space, be as loud as you want to be. The more women realize how liberating it is, the better.

I’m at this point in my life where I’ve never felt more free. I’m relieved to be stripped of my so-called physical agency. The whole concept of our youth is attached to these ideas of “attractiveness,” whatever that fucking means. It means nothing. Some stranger thinks you’re pretty. Who gives a fuck? Who gives a fuck if you walk in a room and nobody’s looking at you, but they’re looking at some young woman in a short skirt. Who really, truly gives a fuck?

It’s based on this idea that, as young women, we think there is only room for one alpha female who will snatch the biggest, strongest warrior, and therefore we will be guaranteed food and shelter for the rest of our lives. Age-old conditioning that we’re still buying into. Those days are long gone. The quicker women realize it, the better, freeing themselves from expectations that somehow we’re supposed to look sexually potent at all times. Our survival depends on that. And if we’re not, we’re practically goners.

You’ve pointed to 9/11 as being a pivot point where strong women in music were silenced.

This actually fucking happened to us: We were told they would only play one woman on alternative radio at the time, and we were not that band. Whether people want to accept that or not is up to them. But I’m telling you, this is what happened to us. It’s not an observation. It’s not a theory. It’s a fact. If you look back and study that period in music, you will see the statistics speak for themselves.

It seems that’s still the case in alternative rock.

Because pop music has dominated the mainstream, and the mainstream is fixated on the song, the culture seems no longer interested in the artist. They’re interested in the biggest, most powerful, most commercial, mainstream success. What can generate the most money? That’s the fixation on the song and not the artist. It becomes a popularity contest, as opposed to creative perspective or artistic endeavor or artistry.

Musical consumption is defined by algorithms. These algorithms require the music to sound a certain way. The BPMs, the production, the vocal sound, they all have to apply to an algorithm to appear on a playlist in order to reach the listener’s ears. It’s wild and weird.

It’s different for each individual listener, but I think a lot of people make a decision about the kind of sound they like and they like being fed that same sound. I am not that person, and our band is not that way. We want to try different stuff and we don’t want to keep honing the same vein over and over again. We don’t want to keep writing our first record. But that causes complications with the algorithm nonsense. It’s the same for a lot of bands that have more esoteric leanings.

There is a shift toward genuine authenticity rather than contrived, marketable “authenticity.”

Spotify allegedly creates artists and bands themselves to not have to pay any royalties. They can just create songs. Once you start that, then people automatically gravitate towards the authentic. Whenever things start to sound completely homogenized, the desire for authenticity rises. That’s what we’re currently seeing over the last couple of years into 2025. All of a sudden, there is an appetite for the strange and the underground and noise and heaviness again. We’ve been drowned in a certain mainstream pop sound for so long, people are a little tired of that and are suspicious of it too.

In one of the many articles I read to prepare for our interview, you said, “I don’t know if I’ve gotten to the point where I love myself,” which made me a little sad, but then, I thought, “Wait, do I love myself?”

I hate this whole thing about you having to love yourself. I hate it. I’m the last person you should talk to about self-love. I don’t even understand it. I think it’s so dangerous to feel so smug and good about yourself that you’re not going to challenge yourself and criticize yourself, and make room for the fact that you can fucking hurt people and you’ve failed and you make mistakes. This whole idea about loving yourself, I don’t get it. I really don’t. It’s awful. I can’t bear the thought of getting to the point where I say, “I really love myself.” I don’t even understand that statement. I don’t even know what it means. Do I guard myself? Yes. Do I respect myself? Yes. Do I put up with bullshit? No, I do not. There’s boundaries I have to protect myself. But using the phrase, “I love myself,” what kind of statement is that?

I’m not criticizing anyone who does love themselves. I’m just saying I can’t get to that place, and I’m not entirely sure I want to. People would argue you can criticize yourself and still love yourself, and I get that, but I don’t know if I want to say the words out loud: I love myself. That feels weird. It doesn’t feel good to me. I respect myself, and I am grateful I am alive, and I’m aware I’ve enjoyed extraordinary privilege and joy and love and excitement. I’ve had a bountiful life and I love that. But I love myself? I don’t know.

Leave a comment