Smack dab in the middle of the final decade before the millennium—when some truly believed the world would end—chaos and catastrophe marked a year of strong attempts towards peace and world change.

The O.J. Simpson murder trial began in January, 1995. The Oklahoma City Bombing took the lives of 168 people in April. The Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia (often referred to as the Srebrenica genocide) took the lives of over 8,000 men and boys, over the course of 11 days in July. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated in November.

And Mexican singer Selena Quintanilla-Pérez was murdered in March by the founder of her fan club.

President Bill Clinton’s efforts to broker peace to Bosnia resulted in an official end to the war in December with the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord. It was a busy (and successful) year for Clinton—a few months earlier, after years of attempting to forge a peace deal between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), he presided over the signing of the so-called Oslo II agreement, which affirmed Palestinian National Authority and the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza and the West bank. It was a time of great hope, which, as you know, has thirty years later to unfathomable despair and slaughter.

Coolio, TLC, Seal, and Boyz II Men finished the year with the top singles; Hootie & the Blowfish had the top album, sales wise. And some pretty incredible women found their voice in the rise of the alternative space.

When asking our editors and contributors to name the “best” albums on any of these lists, they’re encouraged to choose the one that first comes to mind, the one that meant the most to them. None of the albums listed below were chosen for their chart success, but rather their reflection of, or in spite of, 1995. And several of the biggest selling albums of the year—in fact most of them—didn’t make the list.

— Liza Lentini, Executive Editor

Post, Bjork

Two years after releasing her post-Sugarcubes solo debut (1993’s Debut), Bjork gave us Post, an album written after (post!) her move from Iceland to London. Along with Bjork’s signature intentional playfulness is a refined cacophony of genres and the result is a dreamy, epic journey from its first to final note. The spacey house music-esque opening track, “Army of Me,” sets the tone for the next two songs, which take you on an other-worldly fairy tale. But then you get to “It’s Oh So Quiet,” a full on big band tribute—a cover of Betty Hutton’s 1951 single—horns and all, which shouldn’t work but only lends to this musical odyssey. The fact that “It’s Oh So Quiet” was Bjork’s biggest charting single from Post (reaching No. 4 in the U.K.) is a musical mutiny in and of itself, which pretty much defines the fantastic and otherworldlyness of Bjork and her career. — Liza Lentini

Clear, Bomb the Bass

Bomb the Bass’s name comes from main-man Timothy Simenon’s concept of bombing basslines with sonic collages, and my God does he pull it off in this gripping set of tracks. The Naked Lunch-riffing single, “Bug Powder Dust” (sung by Justin Warfield, later of She Wants Revenge), was the gateway drug, prompting me to buy the cassette back in ’95. But then I heard “5ml Barrel” with novelist Will Self talking through working his body over with needles of polluted morphine set to a slowly twisting groove worked up by a team including Atticus Ross (later of Nine Inch Nails). And then there’s Sinead O’Connor dueting with dub poet Benjamin Zephaniah on “Empire”, a throbbing, sensuous anti-colonial dance anthem fusing the words “empire” and “vampire.” How good can one album get? But wait, there’s more. The peak, to my mind, is the casual dream/death funk of “If You Reach the Border,” sung-spoke by Leslie Winer. Have you heard of Leslie? You haven’t? Oh man—you really should: this storied trip-hop progenitor is both oxygen and smoke to many fires burning cooly through the avant-garde. Clear makes dancing a true imaginative journey. Clear forever; forever Clear. — Matt Thompson

Grown Man, Loudon Wainwright III

Loudon Wainwright III distinguished himself from the rest of the early-’70s New Dylans by inventing TMI. And because perfect practice makes perfect, and because he’d been practicing nearly perfectly for a quarter century, Wainwright had TMI down to a lean, mean, and more-hilarious-than-ever art by the time he released this album. How lean? He recorded “The Birthday Present,” a kind of congratulations to himself for having reached 48, in the shower. How mean? The song “That Hospital,” about the near abortion of his daughter Martha, would become the only song that he regretted releasing. And how hilarious? “I.W.I.W.A.L.” It stands for “I Wish I Was a Lesbian” and has lots more punch lines where “I wish I was a lesbian, and not a hetero / I wouldn’t have to deal with men and all their come and go” comes from. — Arsenio Orteza

What’s the Story (Morning Glory)?, Oasis

Oasis’s second album, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, arrived swiftly after their swaggering August ’ 94 debut, Definitely Maybe. Knocked out in 12 days, the album beefs up its predecessor’s visceral pub-rock bluster with fuller instrumentation and ambitious arrangements. What pushed Morning Glory into the stratosphere were its prom-staple ballads: “Wonderwall” and “Champagne Supernova,” along with the syrupy sing-along, “Don’t Look Back in Anger.” Noel Gallagher’s plan to crank out a song a day, and Liam Gallagher’s ability to nail vocals in a couple of takes give the album a burst of immediacy that still rings out three decades later. Not surprisingly, Morning Glory’s songs make up more than half the setlist on their juggernaut Oasis Live ’25 tour. — Lily Moayeri

Jagged Little Pill, Alanis Morissette

At 21 years old, when most people are figuring out life after college, Alanis wrote her magnum opus. Jagged Little Pill was a true chrysalis moment, transforming the Canadian teenage pop star into a raw, confessional songwriter tackling mature themes of bad love, unrelenting perfectionism, and religious dogma. All of it came with an undercurrent of feminist empowerment (and a good dose of harmonica), whether taking a betraying ex to task on “You Oughta Know” or scolding record label executives on “Right Through You.” In the process, Morissette’s honesty and relatability galvanized a generation, particularly women, in much the same way Nevermind did a few years prior. While Jagged Little Pill went on to see 33 million units and was turned into a Tony-winning Broadway musical, its greater impact was in the Pandora’s box it opened of incredible singer-songwriters who took from Morissette’s playbook. Would we have Taylor Swift, Olivia Rodrigo, or Sabrina Carpenter without Jagged Little Pill? Maybe not. — Selena Fragassi

Lost Somewhere Between the Earth and My Home, The Geraldine Fibbers

Carla Bozulich, of the absurdist industrial rockers Ethyl Meatplow, found inspiration in old George Jones and Willie Nelson records for her next band, pivoting hard toward apocalyptic twang for the Geraldine Fibbers. Lost Somewhere Between the Earth and My Home’s dark Americana and cosmic torch songs had more in common with wild-eyed ’80s cowpunk than the tasteful alt-country that was emerging in the ‘’90s, and Jessy Greene’s fiddle duels with Bozulich and Daniel Keenan’s roaring squall of electric guitars on the dreamy epics that bookend the album, “Lilybelle” and “Get Thee Gone.” More critics appreciated what the Geraldine Fibbers were doing then than now—the album was on SPIN’s original year-end top 10 back in ’95—but Bozulich’s throaty wail and surreal lyrics about houses falling down and the devil putting on a party dress are still captivating decades later. — Al Shipley

Wrecking Ball, Emmylou Harris

After 16 solo albums, a 20-year career as Nashville’s most unpredictable maverick, and a 1992 live album that helped save the Ryman from demolition, Emmylou Harris threw it all to the wind with Wrecking Ball. Working with producer Daniel Lanois down in New Orleans, she turned the sound of country music inside out, adding a gossamer distortion to these songs by Lucinda Williams, Neil Young, and Julie Miller. There’s a bit of drift and sway in the way these songs move, as though they’ve been conjured by memory, and even as she ponders the darker implications of death and desire, Wrecking Ball sounds boldly beautiful, lending a dignity to small contentments and overwhelming doubts we all face. — Stephen Deusner

Safe + Sound, DJ Quik

On his third album, Safe + Sound, DJ Quik manages the rare feat of showing every side of himself in one record. There’s lothario Quik on the orgasmic “It’z Your Fantasy,” proof he (and Dre) could’ve been first-rate R&B producers, too. His sharpest shot in the MC Eiht feud, “Dollaz + Sense,” debuted on the Murder Was the Case soundtrack in ’94, tore up the ‘95 Source Awards, and continued on through Grand Theft Auto V. “Keep Tha ‘P’ In It” isn’t just a nod to P-funk, but a full on embodiment of it, while the title track carries Roger Troutman’s talkbox legacy into a coming-of-age tale that could only come out of Compton. Quik even slips in the apex of his many Quik’s Grooves alongside his man Rob “Fonksta” Bacon. For more from this era, dig up vault cuts “Boom” and “Check the Vibes.” — Ade Adeniji

…And Out Come the Wolves, Rancid

…And Out Come the Wolves is seminal. A necessary text in punk. For a punk band to put out a 19-song album where the songs are longer than 1 minute alone is a feat. For all of them to be good is another victory. For all of them to be singularly good in their own unique ways? Unreal. A masterclass explosion of weaving pop hooks, street punk attitude, tales of heroes and villains, gang singalongs, and some of the best basslines on offer in punk. As an often uncool and always un-tough guy, listening to this album makes me feel like a cool tough guy. It’s the Tim and Lars songwriting power axis operating at its highest level, and its DNA is all over punk to come. — Brendan Menapace

Wowee Zowee, Pavement

A huge left turn from a band that never traveled in a straight line, Wowee Zowee, Pavement’s gloriously uneven third album, confounded the listening public upon its release. Beginning with an arch acoustic ballad invoking possibly expired Brazilian nuts and moving on to chunky Shudder to Think tributes (“Rattled by the Rush”), cockeyed Grateful Dead-adjacent rambles (“Grounded”), and wistfully shaggy odes to ambiguity (“Father to a Sister of Thought”), among other pit stops in the noisy, impulsive, and enigmatic, Wowee Zowee effectively killed Pavement’s chance at even Buzz Bin-level success. But by intently following their own ramshackle, self-sabotaging instincts, indie rock’s most diffident and ambivalent standard-bearers found a way to win on their own curious terms: by dropping out of the game. As a member of the Meat Puppets—another key Wowee Zowee touchstone—once said: “If you don’t aim, you’ll never miss.” — Reed Jackson

The Bends, Radiohead

This is when Radiohead became Radiohead. Their 1993 debut, Pablo Honey, was dismissed in the early Britpop era as an uneven collection with one remarkable anthem of self-loathing in “Creep.” It barely hinted at the soaring sci-fi guitar rock to come on The Bends, as bandleader Thom Yorke sang of his warring impulses for malaise and defiance in response to the discomfort and endless disappointments of modern existence. This noisy, gorgeously melodic masterpiece opens with the undulating atmosphere of “Planet Telex,” as reluctant guitar hero Jonny Greenwood slashes through the electronic haze. The disarmingly understated “Fake Plastic Trees” is the obvious emotional follow-up to the band’s earlier mega-hit, but cuts even deeper, Yorke’s aching falsetto as evocative as contemporary Jeff Buckley. The Bends was a startling revelation, and the true beginning of a career inspired by the provocative and experimental. — Steve Appleford

Different Class, Pulp

“Jarvis Cocker is sex.” This is how my college classmate sold me on Different Class, and 30 years on, the album remains a seductive rave. It’s a collection of dance floor come-on’s mixing their art-pop with flourishes of glam, disco, new wave, and chamber. But underneath the grooves, Cocker lives up to my pal’s description, exploring sex in many forms, from lustful invitations to infidelity (“Pencil Skirt”) to imagined teenage crush reunions (“Disco 2000”) to bedroom doubts (“Underwear”). Its centerpiece is arguably Britpop’s greatest single, “Common People,” a provocative anthem about the strange bedfellows of sex and social class, full of caustic humor and sharply drawn observations. It builds to a joyful climax that makes you want to shout, just like… well, you know. — Brendan Hay

Labcabincalifornia, The Pharcyde

The Pharcyde cut through the frenetic noise of West Coast gangsta rap with their 1992 debut, Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde, a fresh, innovative amalgamation of jazz, boom bap hip-hop, and slick humor. For their sophomore effort, Labcabincalifornia, they enlisted beat magician J Dilla for a big chunk of the production, which resulted in a 17-track opus that includes the now-classic tracks “Runnin” and “Drop.” Other songs like “She Said” and “Y?” illustrated the Pharcyde’s versatility as they explored more mature themes about life and relationships. Although it turned out to be “The E.N.D.” for them, the album further cemented their elite status within the culture. — Kyle Eustice

To Bring You My Love, PJ Harvey

To Bring You My Love is when Polly Jean Harvey became PJ Harvey. After splitting with the nucleus of her first two records—bassist Stephen Vaughn and drummer Robert Ellis—Harvey used her newfound freedom to branch away from the stripped-down punk noise that informed Dry and Rid of Me and reached towards the damaged American mythos that propelled much of Nick Cave’s early songwriting. To Bring You My Love is stranger, denser, and more unsettling than any album Harvey made prior. Produced along with John Parish (who would become a frequent collaborator) and Flood, To Bring You My Love is not only one of the best records of 1995 but one that would provide a template for three decades of original and arresting songwriting. — David Harris

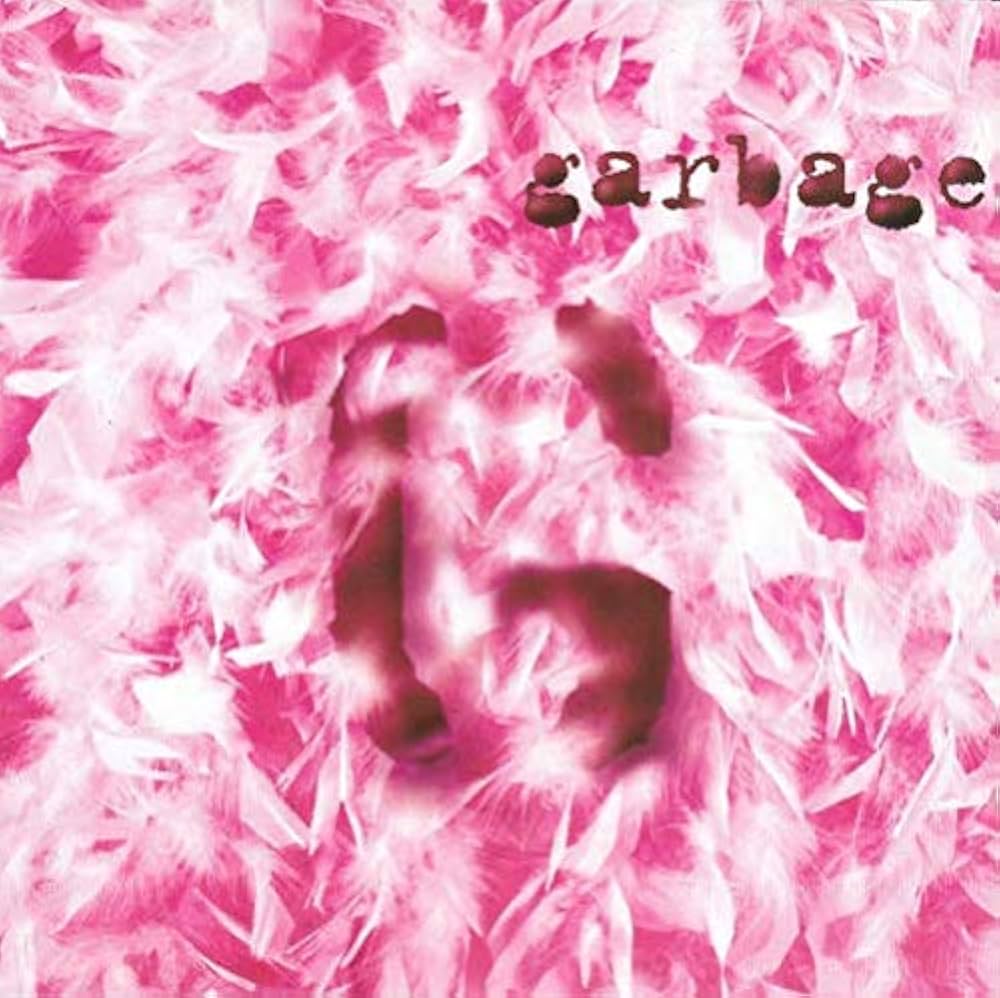

Garbage, Garbage

Butch Vig had some stellar producing credits—including Nirvana’s Nevermind—when he and his Wisconsin-based Smart Studio cohorts Duke Erikson and Steve Marker were joined by Scottish singer Shirley Manson to make music as Garbage, and the resulting debut was anything but disposable. On the contrary, this intro to the four-piece remains one of the most polished yet evocative albums of the ’90s, lyrically and rhythmically capturing the moody urgency of the era, when grunge and dance music redefined what rock music could be. Behind the boards and the drum kit, Vig’s alchemy with Manson in particular made gothy/groovy hits like “Stupid Girl,” “Queer,” and “Only Happy When it Rains” feel timeless. In its entirety, the multi-platinum recording still sounds undeniably sultry two decades later and as sonically significant as anything Vig ever worked on. — Lina Lecaro

Leave a comment