B-Real drops a bombshell mere minutes into our interview. Cypress Hill’s 1993 juggernaut, “Insane in the Brain,” was initially written as a diss track aimed at “Treat ‘Em Right” rapper Chubb Rock. Suddenly, after more than 30 years of hearing the Grammy-nominated song in heavy rotation, it was no longer perceived as just a weed anthem about being “loco”—it had way more depth than that.

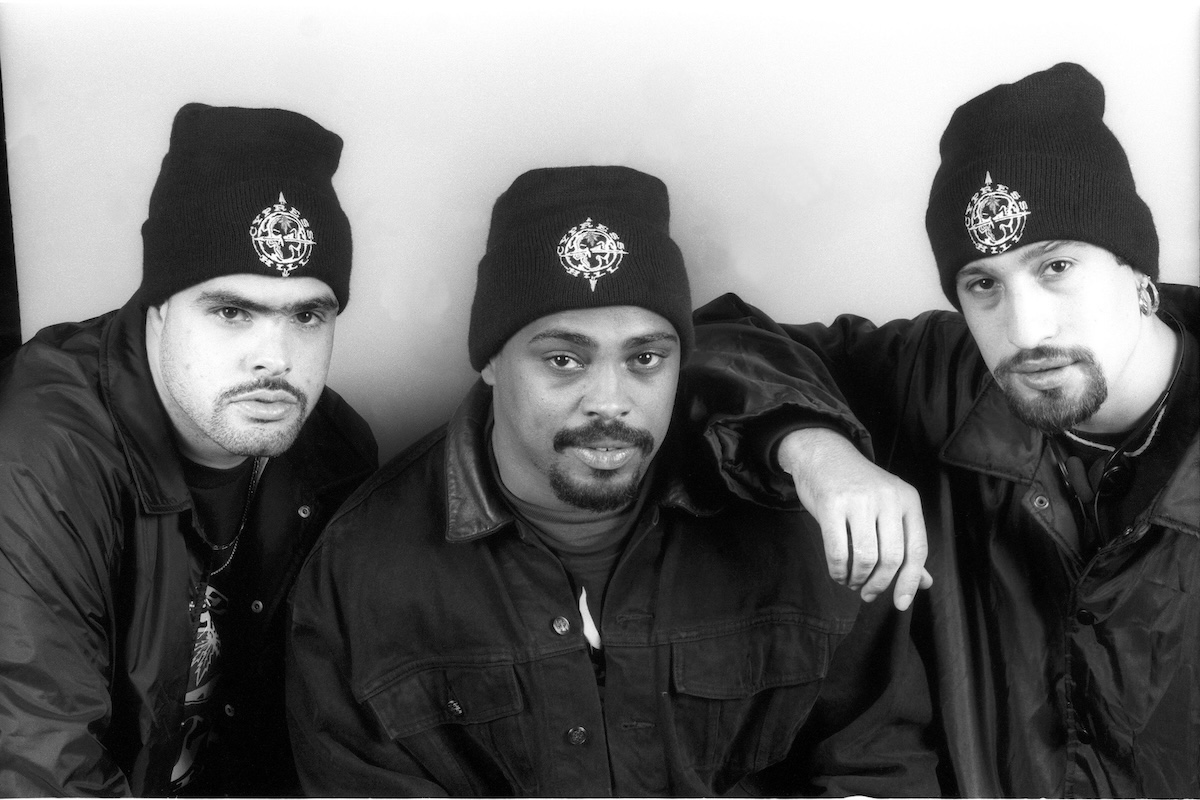

Serving as the lead single from Cypress Hill’s sophomore album, Black Sunday, “Insane in the Brain” launched the Latino hip-hop group into another realm, introducing B-Real, Sen Dog, Eric Bobo, and DJ Muggs to a mainstream audience and making them superstars in the process. Soon, B-Real couldn’t go to the local grocery store without being recognized or hounded for an autograph, a pivotal period he describes as a “whirlwind.”

More than 30 years later, B-Real still gets a rush when he performs the song. Not only is it a crowd favorite, it’s also a reminder of how four kids from South Gate, California, were able to permanently change the hip-hop landscape with their heavily rock-influenced sound. Now with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, millions of albums sold, and tour dates across the globe, Cypress Hill remains among hip-hop’s elite.

Here, B-Real breaks down how “Insane in the Brain” made them a household name and why he’ll never tire of performing it.

The Beginning of the Beginning

I was 23 years old in 1993. I believe I was living in Venice at this point. But we weren’t home much. We were on tour a lot still from the first album going off and on. But by ’93 we were releasing Black Sunday and so we didn’t really have too many breaks. We didn’t see home too much, because we went from touring massively to promoting our first album still. And then it started catching fire and we did even more shows. Due to the lack of radio play, we knew we had to get out there and play shows to win people over, to compensate for not having radio. So we spent a lot of our time on the road. It started really picking up in ’93 because when we released Black Sunday, none of us realized how impactful that album was going to be. It was like a whirlwind for us.

The First Spark

We were pretty obscure in the beginning. People were hearing about it, but they didn’t really know too much about us. We were kind of in a bubble, but we were still kind of like a mystery to some. When Black Sunday hit and “Insane in the Brain” got out there, we did not anticipate it was going to be that big of a song. We knew it was a great album song, but we didn’t know what it would do commercially. That was totally a call from Sony Music. The obscurity went away and we were now all of a sudden very public and out there. We used to be able to go to a flea market or swap meet—as we call it here in Cali—basically unnoticed.

When Black Sunday drops and “Insane in the Brain” starts getting this major rotation, that all stops. We could not go anywhere without being recognized and the swell of people that would show up to our shows was crazy. We didn’t realize how big it was, because we didn’t anticipate that. Our first album, when we put it out, it was out for close to six months and it got on the Billboard 200 chart, probably at 170 or something. Then it dropped to 180 and then dropped off the chart completely. Then “How I Could Just Kill a Man” drops and DJs start flipping it. It starts getting in mix shows and stuff like that and all of a sudden there’s a new breath of life that happens for us. And then Chuck D and The Bomb Squad are working on the Juice soundtrack. They applied “How I Could Just Kill a Man” to one of the most pivotal scenes, which created the spark for us.

The Rebound

When that song started hitting all over the place, our first album that had dropped off the charts had now gotten back up on the charts and made a slow crawl to No. 5. And when it got into the Top 5, now we’re releasing Black Sunday, so when we released Black Sunday we had created all this momentum from the first album that we didn’t know about and so the album debuted at No. 1 and we had our self-titled album at No. 5. We became the first hip-hop group to have two albums in the Top 5 at the same time.

Yabadaba—What!?

If I’m remembering correctly, it was peeled from a line that I had in one of the other songs. I think it was, “Holding the head insane in the brain / You get the bullet and a hole in your head, a fucking hole in your head.” Muggs had an idea to make that “insane in the brain” part of the chorus. As we were recording the album, we saw this Chubb Rock song called “Yabadabadoo” and in the song, he sort of quotes a line from “How I Could Just Kill a Man” that sounded like a diss. He says something like, “And you know we had to watcha, time for some lyrics,” and in our song, we say, “Time for some action, just a fraction of friction.”

So being young and hot-blooded as I was back then, I took it as a diss. I had never talked to Chubb Rock and I was a big fan of Chubb Rock. We had done some shows together and all that stuff. So when I heard that I was a little taken aback and I said, “Fuck it. If he’s gonna give me a subliminal, I’m gonna give him one.” At the time he was calling himself “The Flamboyant One.” That’s where I started the line, “To the one on the flamboyant tip/I’ll just toss that ham in the frying pan.”

Is It or Isn’t It a Diss?

Chubb Rock and I never spoke about it. We still haven’t. And it maybe was a surprise for him to know that song was directed toward him. But you know, when I heard that “Yabadabadoo” shit—and I loved the song—but then I heard that and I was like, “What is that—a fucking diss?” Back then there was no social media, so you couldn’t reach out to somebody. We were hostile. We were all kind of hostile dudes in the first place. We took that as, like, “Alright, if you’re dissing us, we’re gonna go right back at you.” That’s how that song was created. It was actually a dig back at Chubb Rock. So in my verse, I was talking to Chubb Rock. That’s how that song came about. And we didn’t anticipate it being a single. We thought it would just be a really dope song on the album. Who knew Sony was gonna pick it? No one back then bothered to ask us what the song was about. They just thought it was a crazy song—like go crazy and have fun and all this other stuff.

Props to Chubb Rock

I still got mad respect for Chubb Rock. He was always one of my favorite MCs because he’s really dope. It was just that I felt the need to respond. If I was wrong, I will apologize to my man. I’ll say this, he created another spark. We don’t make the impact without that song, so I gotta say thanks to him. If I was wrong, I gotta apologize and say thank you ’cause either way, he was the inspiration for that song and it ended up being the shit that launched us. “How I Could Just Kill a Man” launched us, but “Insane in the Brain” took us to another level.

The Way of the Walk

I was probably in the studio with Muggs, because we used to write a lot of things right there in the studio. Other times I’d drive into the Hollywood Hills. Most of the shit on our third, fourth, and fifth album, I’d go into the hills and look over L.A. and all that shit right from there. But the first two albums, they were pretty much spot writing in the studio, in the moment. There was only a couple songs that I wrote away from the guys like “Stoned is the Way of the Walk.” I wrote that by myself on a bus. It’s the only or one of the very few songs that I didn’t put the ink to the paper. I thought of it and just memorized it on my way to the studio.

The studio was in Hollywood at Muggs’ crib. We’d either go to his house or rent out a studio for the day or whatever. When we were just doing demos, it was his house. But once we got our deal with Ruffhouse, then it was going to the studios and sometimes having a spot right there because we didn’t like to waste time or money.

Ballin’ on a Budget

Even if you got what was perceived as not such a big budget by a major, it was still pretty fucking substantial and significant in comparison to what you might get today. So for a group like ourselves that were having that kind of success, it could be anywhere from a $100,000 to $200,000 video budget. These days you could do a video for five fucking grand or even less than that. But that’s the type of money that they were spending then. Because realistically, when you were hiring a director back then, you were not just hiring a director, you were hiring him and his team. And most likely, they were going to have to lease out the equipment—the lighting, the cameras—because back then, nobody owned their own shit. You very much had to go to a company and say, “OK, I need all this gear for X amount of days and blah, blah, blah.” Then going into the editing, all that stuff cost a lot of money. They put out large-ass budgets to be able to accommodate the director. Just like producers were very significant, some people would look and see who was the producer of this group or this music, and they would get excited about it. Sort of like the way with Dr. Dre and stuff like that. When people hear Dr. Dre doing something, they gravitate to it. So people would look at the album critics and see what producer is rocking the album. Like a Rick Rubin or somebody.

The Magic of Josh Taft

Video directors in the ’90s and in early 2000s were very much like that. If you had one of the guys like Hype Williams or Paul Hunter or Spike Jonze, MTV was going to be like, “Oh shit this must be a good video. We should check it out because this director or this producer is behind it.” Those guys were very important back in the day as it related to the video just as much as the producer was important. So for “Insane in the Brain,” it was Josh Taft. He was really good, and we clicked with him really well. We loved his ideas. It was his idea to do it as a live performance and then mix it with the psychedelia imagery that ends up making the video. That’s who he felt we were. He definitely had it locked in terms of the visual of what Cypress Hill was at that time. And I thought he did a masterful job out of all of our videos. It’s one of my favorites because he understood who we were.

Free Admission

Our one suggestion to him was if we’re going to film it like it’s a live video, we should probably actually throw a live show, let people in for free and play our music. And in between, we could film these bits for “Insane in the Brain.” So we did just that at the DNA Lounge in San Francisco and it ended up working beautifully. Josh is a master. He totally fucking killed it.

Breaking the Mold

I don’t think any of us imagined it. We were just sort of living in the moments and trying to keep up with it all. And who knew that fucking all these years later, we’d still be doing this shit. The industry didn’t give groups like ours that came from the ’90s a chance. Primarily in hip-hop, they didn’t think that longevity was possible for us. They thought a lot of us would be in for one or two records and then be out. That was the trajectory for a lot of hip-hop artists, and we sort of changed that for ourselves. We broke that mold, and here we are 33 years later. They were wrong about the genre because they thought the genre was a fad, that it was going to play out. And then they were wrong about a lot of the artists that they thought would fizzle out after the first or second album. A lot of us are still around doing significant shows today, selling out shows and being relevant enough to be asked. A lot of us are doing this right now and it just goes to show you that one person’s opinion doesn’t really dictate the trajectory of your career. I think people—even record labels—are realizing, “Oh shit. Maybe we don’t have the latest with little what’s-his-face, you know what I mean?”

All About Timing

I feel great about performing it. I know a lot of artists try to run from the shit that they’ve played so much and want to do something else. But me, as a music fan, when I go see someone that I love, I want to hear those songs that made me fall in love with that artist.

It would be unfair for me to deprive the fans of the shit that I know they want to hear. Because traditionally, you could put out new music right now, even if you’ve been around for 30 years, and no matter how much those fans love you, they don’t necessarily gravitate to that music. If you went to play a show, they’re all showing up, but they want to hear the classics.

You cannot force feed the new stuff because it’s stuff they have to take time to learn and digest and process and all that stuff. Sometimes that shit don’t go over when an artist decides, “Well, I’m going to be an artist and I’m not playing any of the old shit. I’m going to play the new stuff.” No. They end up losing people like that. It’s a fine line. You got to find the ways to be able to promote and market the new shit within your set but not overdo it to where you’re pushing your fan base away because it’s too new for them.

Drop a Bomb On ’Em

I remember we were so confident in our show that we were gassing the biggest songs, right in the first 20 minutes. But the way we looked at it was that we didn’t just have hit singles. We had hit albums because when you look at it, our albums sold more than our singles. “Insane in the Brain” was a top-selling single for us. Same with “(Rock) Superstar,” “Illusions,” and “Tequila Sunrise.” All those singles did fairly well, but all the albums were the ones that sold.

We felt in our set that if we wanted to play the big songs first and just take them on a journey, that we had the material to do it. And we still feel that way. We’ll put the big songs in the front and say, “Fuck you, we’re going to still smash this set, and I dare anyone to come after it.” That’s the mentality we have. Traditionally, you want to put the bigger songs more toward the middle and end to keep the people around, but we feel like our show is dynamic enough that people are going to stay till the end. We try to give them what they want as opposed to what we want to do. And then we find a way to make it work. We find a way to make it compelling, interesting, and entertaining.

Advice To His Younger Self

Keep doing what you’re doing, kid. You’re doing good. Don’t give up on your dreams, kid. You stick with this shit. You got this. One day you’re going to own dispensaries, you’re going to travel the world, you’re going to do it all. You’re going to have a podcast, you’re going to have a show. It’s gonna be great. Have patience. Just chill.

Leave a comment