Blue Chips is a monthly rap column that highlights exceptional rising rappers. To read previous columns, click here.

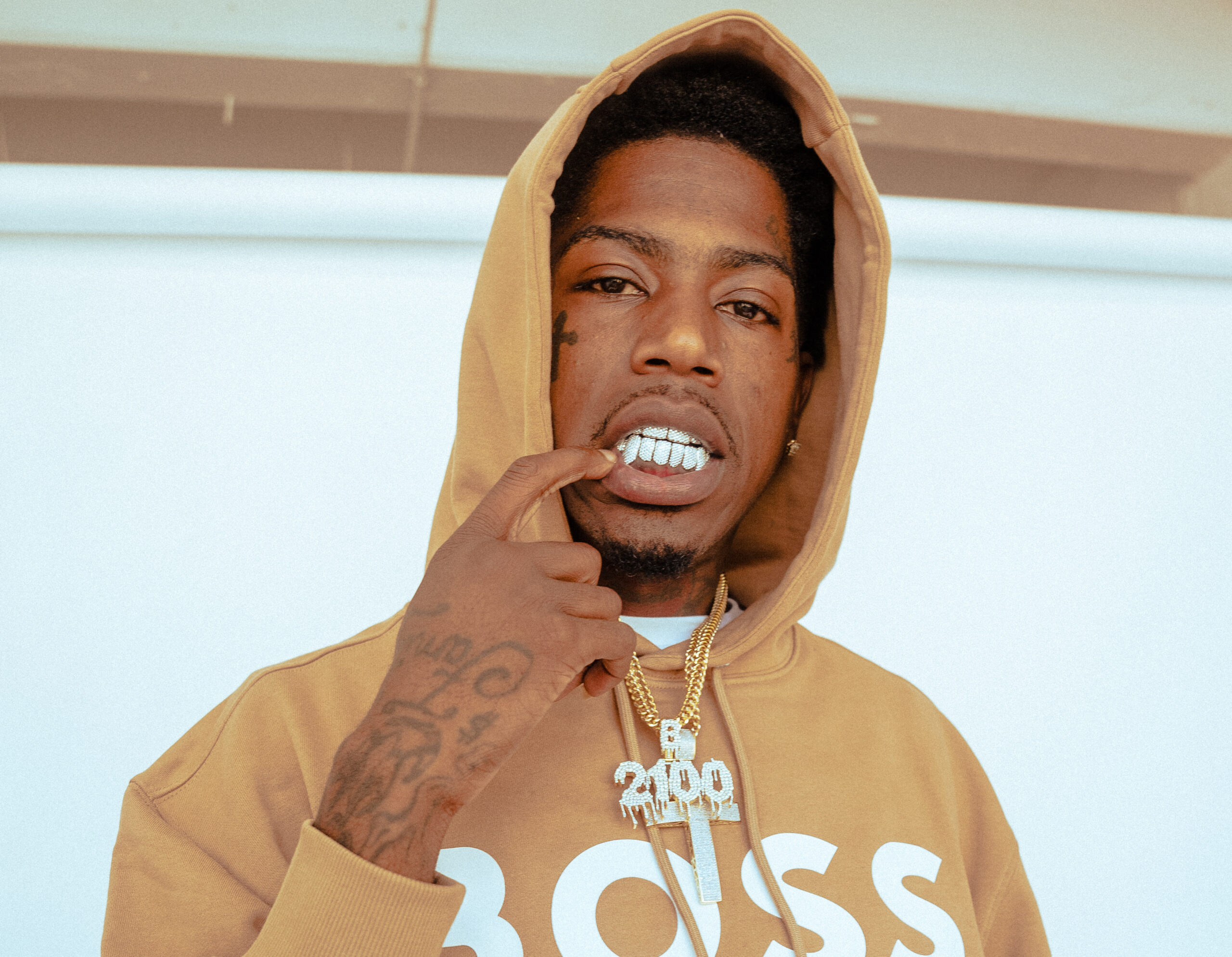

Young Slo-Be is likely older than his peers in Stockton, California’s burgeoning rap scene, but he slyly refuses to reveal his age. “I tell people [my age] all the time,” Slo-Be says over the phone, his smirk practically audible before he delivers the canned punchline: “I’m 2100.”

Slo-Be doesn’t claim vampiric immortality, just an undying devotion to the 2100 block of Nightingale Ave. (aka “the G”) in the southeast section of the Central California city. Though his family lived in a comparatively quiet cul-de-sac, he walked to the perennially hot corner of Seventh and Nightingale every day. Slo-Be stands beneath that street sign on the blood-red cover of this month’s Southeast, throwing up his set in salute.

Southeast and Slo-Be’s catalog dating back to 2018 is almost entirely frontline dispatches from the G. Written for locals, they are coded chronicles of Stockton gang life and its attendant violence and carceral consequences, the finer points of pimping, and money-making trips out of town. Slo-Be is one of the best rappers in a city brimming with talent. Rhyming with nonchalant swagger and menace, he’s perpetually oscillating between a wry smile and a piercing glare, delivering each line in a forceful yet conversational register that often descends to a whisper. Especially when his voice is lower in the mix, Slo-Be tracks sometimes sound like you’re overhearing half of a wiretapped conversation.

“I don’t like yelling in the booth. How I sound on the phone is how I sound in the booth,” Slo-Be says. “It’s the same on and off record.”

On record, Slo-Be’s scored by rearview rattling drums, percussion seemingly sourced from car crashes, and alternately rubbery and squelchy synth bass. It’s a hybrid of Bay Area mobb music and the “nervous music” sound popularized by Drakeo the Ruler, the late Los Angeles slang maven who Slo-Be recorded two songs with in recent years (e.g., the excellent “Unforgiveable”). Like his childhood idol, NBA legend Kobe Bryant, Slo-Be scoffs at the competition or strikes at will in verses filled with basketball metaphors and puns. Every “ooh wee” and “ah-ah” he drops to fill negative space or allude to illicit activity is analogous to a devastating pump-fake or crossover.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Bryant also inspired Slo-Be project titles like Red Mamba — if you know, you know — and all three volumes Slo-Be Bryant. Last year’s Slo-Be Bryant 3 features “I Love You,” a sinister R&B-sampling slap about a toxic relationship that soundtracked a recent TikTok challenge. The father of two only caught wind of the song’s virality from his eight-year-old daughter. At the time of this writing, “I Love You” has nearly 15 million plays on Spotify alone. Though Slo-Be’s seldom on TikTok since creating an account, the profile bump has been, well, tight.

“You seeing big stars post [my] shit. Models, rappers, singers, sports people, ESPN—that type of shit,” Slo-Be says. “It’s like, ‘Shit, we blowing up.’ It’s tight.”

Before the success of “I Love You,” Slo-Be was a star in the G. Kids stop him in the street whenever he visits his old neighborhood, undoubtedly familiar with the many Slo-Be music videos with hundreds of thousands of views. When he was their age, Slo-Be played guard for a local AAU team, dreaming of being the next Kobe between weekends spent at the since-shuttered Hammer Skate Rink and Da Candy Shop. The latter was a 6,500-square-foot teen club that played NorCal artists like Mac Dre, Lavish D, and DB. Shortly after Da Candy Shop opened, the Stockton Planning Commission considered shutting down due to drug and gun-related arrests at and near the club. Eventually, they did just that.

Both Hammer and Da Candy Shop were the few social and recreational outlets in a city with a current poverty rate of 16.8% (over 5% higher than the national average) and historically high levels of unemployment. In other words, the root causes of Stockton’s gang activity and elevated homicide rate are no mystery, mirrored in every institutionally marginalized and underfunded hood nationwide. Though Slo-Be’s father was an active gang member, Slo-Be Sr. also had an in-home recording studio. Youg Slo-Be overheard his father and uncle Effn Mccoy (fka Cyco City) — both originally from San Diego — record until, at age 12, he snuck in and recorded himself.

Slo-Be graduated high school by the seat of his sagging pants and moved on to robbing, pimping, and catching cases, the nature of which he’s understandably reticent to disclose. Poor academic performance prevented Slo-Be from playing on his high school basketball team, but he’d continued to record at home. With no nationally recognized Stockton rappers, however, he didn’t view rap as a viable career.

“I had to get some money out here in these streets. No one made it out of Stockton with rap. At that time, it was unbelievable,” Slo-Be says. “I’d been rapping, but I didn’t know you could get paid for this shit without a record label. Growing up, I thought I had to save and move to L.A. or something and get noticed by a record label just to get on. I didn’t know you could get your own buzz and your own money.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

Once Slo-Be summoned the courage to release 2018’s Smurkish Wayz on SoundCloud and YouTube, he saw plays and view counts gradually rise. “Do Wit It” slapped from cars in Stockton, and he began working with the late Sacramento rap star Bris. When a friend hipped Slo-Be to digital distributor CD Baby, everything clicked. He uploaded 2019’s Slo-Be Bryant and began racking up tens of thousands of plays. He’s been on a tear ever since, earning independent rap money from millions of collective plays across streaming services, dropping one refined project after another, working with fellow G-native and longtime collaborator EBK Young Joc, and releasing music in conjunction with Oakland-based blog-turned-media company Thizzler on the Roof.

“[Rap] is my full-time job. Keeps a nigga off the streets,” Slo-Be says. “I love my job. I was destined to do this shit. I’ve been dreaming about it.”

Near the end of our conversation, I speculate that, given references to certain rappers and basketball players, Slo-Be is either in his late 20s or early 30s. He laughs, only concerned with growing artistically and living longer than far too many fallen peers.

“You ain’t young forever. You have to mature somehow some way in your music… I’m trying to make it to 3100.”

Leave a comment