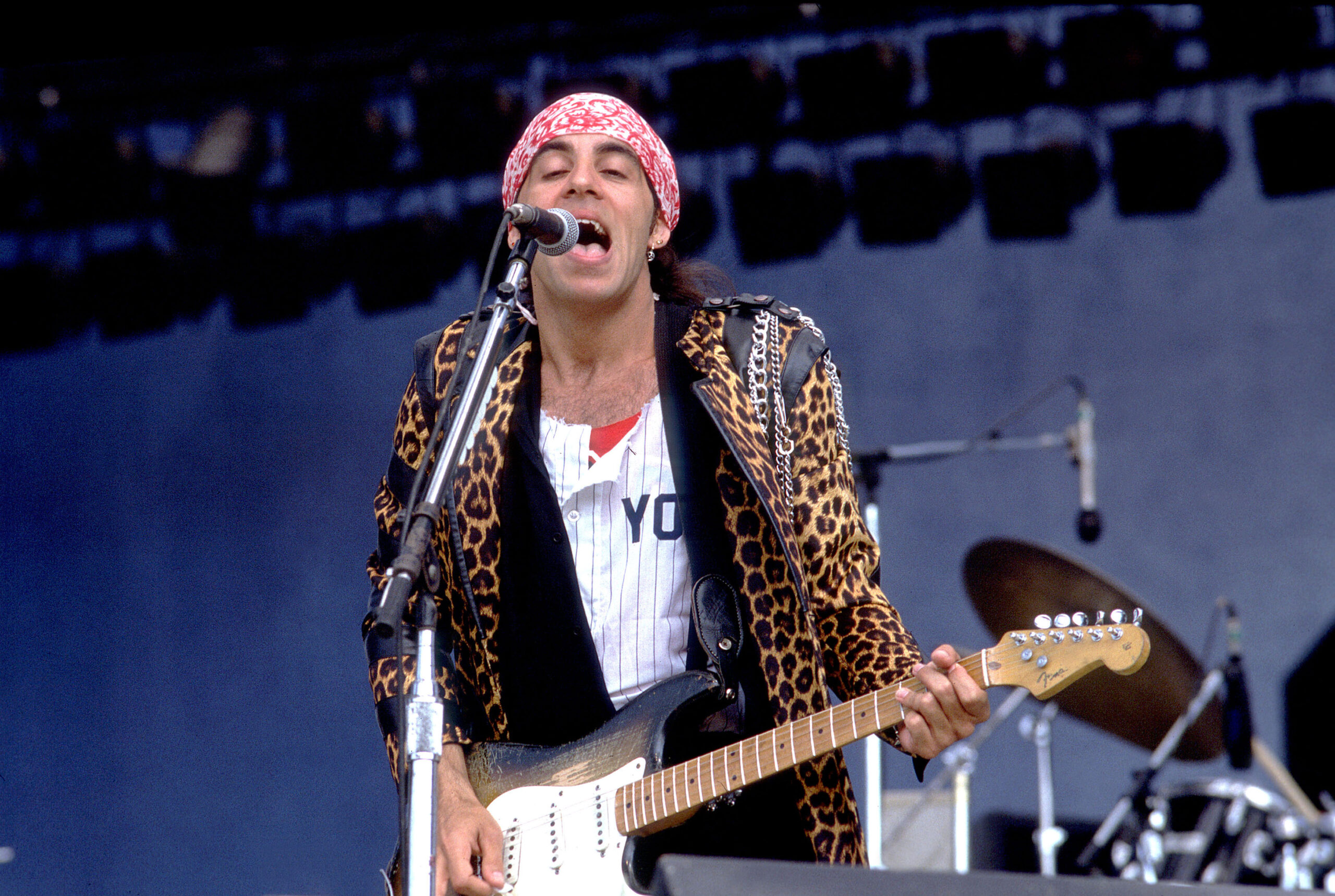

There are many Steve Van Zandts (although, ironically, not Steve Van Zandt, his publicist gently rebuked me, which comes as no small embarrassment since that’s what I’ve been calling him for the 35 years I’ve known him). There’s Little Steven, Stevie Van Zandt, Miami Steve, and of course Silvio Dante, Tony Soprano’s consigliore.

There’s also Dr. Steven Van Zandt, awarded an honorary degree as a Doctor of Fine Arts by Rutgers University, who got a typically inspiring commencement speech in return. And UN honoree Van Zandt, recognized for his incredibly effective political activism, including his central role, with Peter Gabriel, in International Peace Day, and for making the western world viscerally aware of the horrors of apartheid with his anthemic “Sun City” song, and later film and persistent campaign, extorting artists not to play the glittering, Vegas-style resort in South Africa, planted in one of the makeshift regions where the white government forced the black population to relocate.

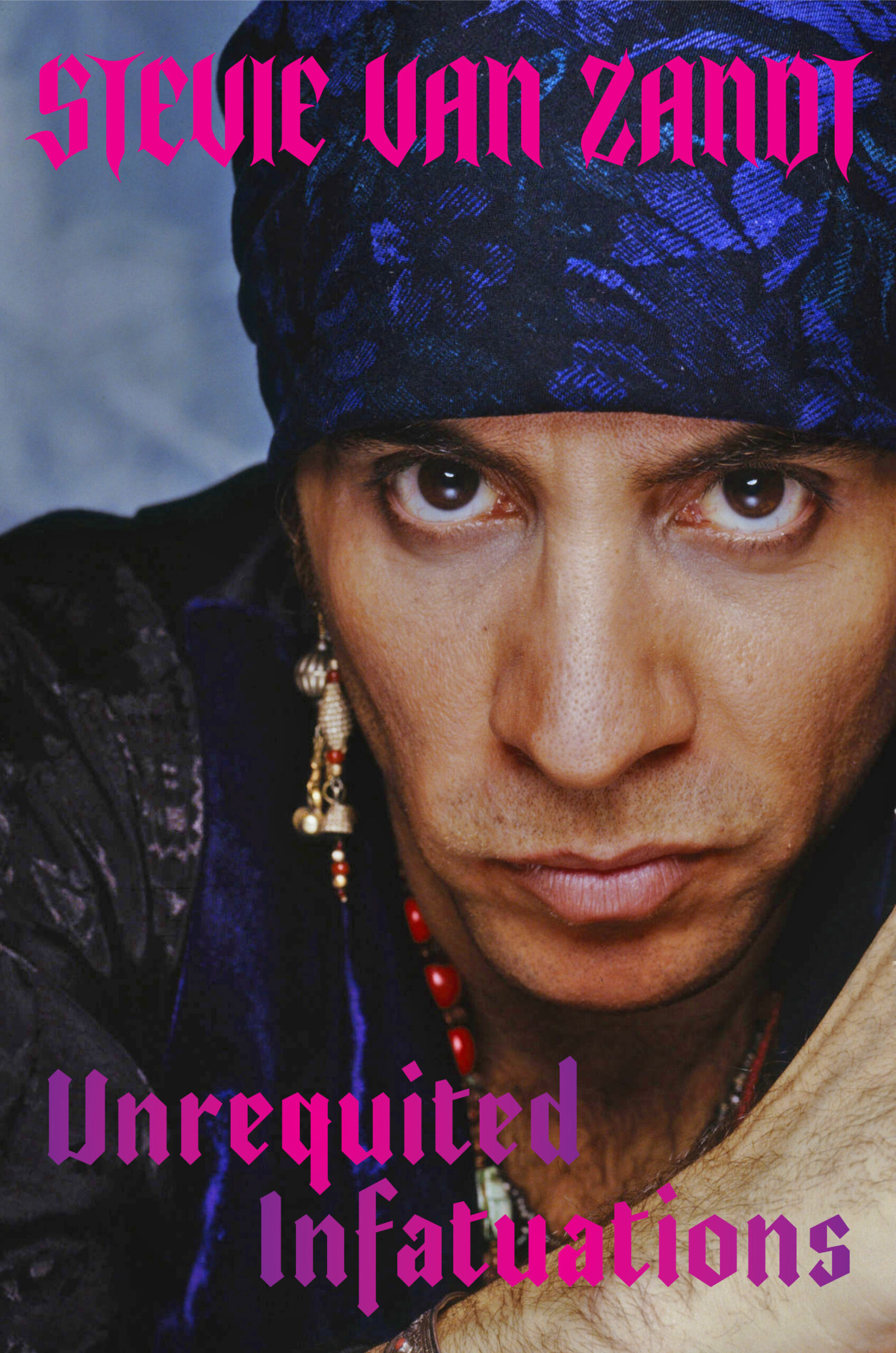

There’s now legendary radio show host Steven, as creator of the gold standard Underground Garage on Sirius, and there’s best selling author Van Zandt, whose curiously titled autobiography Unrequited Infatuations is a literary masterpiece and page turner and one of the best books ever written about a life lived in music (and beyond, because Van Zandt always went beyond).

And before he was an author, he was an auteur, co-producing and co-writing and starring in the excellent, quirky and very funny Lilyhammer, a show about a NY mobster who chooses the nearly Arctic Norwegian town for the Witness Protection Program because he remembers it from the Winter Olympics. Lilyhammer was Netflix’s first produced series, back when streaming was an add-on to your DVD subscription. Remember that, it’s going to come up in a pub trivia contest one night.

Finally — although I suspect “finally” is a flimsy word here, soon to be swept away as redundant — there’s educator Van Zandt, who in 2018 toured his band Little Steven and The Disciples in support of the visionary TeachRock program, which incorporates, incredibly successfully, in tens of thousands of schools across the country, a music history curriculum into the classroom. Steven has become an apostle for this simple but brilliant program, and calls it one of the things he’s most proud of. He says teachers constantly thank him, as “they were tearing their hair out trying to get these kids to concentrate.”

We’ve been friends since he first used to wander up to SPIN’s offices, conveniently above a Tower Records store in upper Manhattan, to hang out for a while, talk music, politics and the crazy, awesome, wonderfulness of life. Just as we did for this interview.

SPIN: You said to me recently that rock ‘n roll has become irrelevant. How did that happen?

Steven Van Zandt: It’s irrelevant in terms of the industry. We must hasten to add that live it is the biggest thing.

The last few generations just don’t really go out to see bands on a nightly basis, which is what we did, but they will go to festivals. I think they’re a very healthy way of keeping things alive.

In the industry itself, we went back to a pop era. The rock era lasted — I clocked it almost exactly 30 years from the Rolling Stones to Kurt Cobain’s death. Almost exactly since ’65-’94. Then we returned to a pop era.

“Pop era” is where we found rock in the first place. Now we’re back to a pop era, which is mostly mediocre stuff but that’s okay. Rock has now returned to the cult, perhaps where it belongs. It was a cult in ’65 and ’66 when we staged the coup on the charts with The Beatles, or British invasion, and now we’ve returned to the cult where I think, naturally, in a lot of ways, rock belongs.

The infrastructure’s changed, you don’t have the local clubs, the local theatres necessarily. You don’t have the tour support, that’s long gone. Every band gets sick when I tell them this, but bands got $250,000 to make a record. You also got $250,000 to tour. That was normal. Because you have to develop. That’s where greatness comes from. Greatness comes from development. Nobody’s born great.

All of that and plus radio playing local bands– I would call the biggest FM station in town, talk to the DJ and request songs. That’s the other reason why rock has now withdrawn from the mainstream. MTV both gave it a boost to ridiculous sales but at the same time, it helped to kill it. We used to be very excited when a band came to town. You could barely get a picture of them in a magazine.

There was a mystique, which MTV eviscerated.

So exciting. I’ve often told the story of my bass player running into rehearsal with a magazine, “Look, look, so and so is white!” I wouldn’t even believe him. That was the state of the media back then. I thought they were a black group. [Laughs]

You’ve always been very political. Can America heal after the four years of Trump’s divisive presidency?

Everybody wants to think so. I think it’s going to take a long time, much longer than people think because we’re all prejudiced to some extent, I think that’s part of human nature, actually. Civilized people suppress it. That’s just how we get along in a civilized society.

Well, for the last the four, five years now, we’ve been told to not only not suppress your racism and prejudice but let’s celebrate it. People can think what they want to but in my personal opinion, with a 40% approval rating all along, while being the biggest mass murderer in human history, certainly in American history, not quite at the level of the big boys but competing, Trump will have murdered when this is said and done, they’re saying 900,000 now [COVID victims], when the choice was really, really quite simple. If some stupid hippy guitar player can come up with it, I’m sure some politician could come up with it. It was three simple things. Quarantine, stop all the bills and give people money for food, period. End of virus in three months, done. We would have come out, celebrated July 4th and had a party.

The [racism] problem is our fucking civil war never ended, man, and this is like we’ve never become integrated. I just feel until we’re truly integrated and every white person knows somebody that’s black or a bit of diversity in your neighborhood, it’s never going to change.

I’ve heard these superficial changes for 50 fucking years! “We’re going to do this. We’re going to do that.This reform and that reform.” The truth of the matter is, the biggest scam the white population has ever perpetrated on the black population was convincing them that the black neighborhood was their idea. What are we doing with black neighborhoods? When are we going to invite our black population to join the rest of us in America?

Until that happens it’s a fucking joke, and then this rampant virulent racism ain’t going nowhere, man, I’m sorry. It ain’t going to change.

I think Gen Z might be the first generation that’s going to break that down.

Me too. I have great hope for these teenagers right now, they don’t even understand prejudice, they don’t understand racism. They’re totally like, climate is everything, which is obvious to them, and they don’t care if you’re black or white, or gay or straight, they just don’t. There’s no question in their mind. Which I love.

But there’s going to be an exceptions, you know? Psycho parents who pass along their prejudice. But mostly I do have faith in those teenagers.

How do you find the new musicians for the radio show?

For the first, God, I don’t know, 10 years, I had to go and find them. We started 2002 I guess, and at that time rock was at its absolute lowest point. I mean, you actually could play every rock record being released at that time, there were so few. So we started going around to the local record stores — there were still record stores in those days — I was touring by then. I’d go to local stores and then local radio, everywhere from Oslo to Stockholm to wherever I was.

They would make some suggestions and I would discover some that way. We just asked the local critics, the local journalists and they would recommend people, then we’d listen to everything and pick a song, then I said, “Wow, there is still a very healthy rock scene, especially in Scandinavia, and we want to support it.” Eventually friends started recommending friends, they’d send us stuff. Then, of course, the independent record companies started sending us stuff. For years, we’d just go round finding.

You are like the John Peel, the famous BBC radio DJ, of America.

Kind of, yes. I saw myself as partially Ronan O’Rahilly, who started the Pirates [outlaw radio stations in Britain]. Radio Caroline. They were everything, and they really, really were an extraordinarily important part of history.

I got Ronan out of seclusion. He went into seclusion when he found out that the SAS were going to whack him. Oh, it’s a great story there, really great. The UK Government supposedly seriously considered killing him because he was having such an effect, he was all those miles out [offshore] that they could get away with it.

Enough guys in the SAS said, “Listen, we don’t want to kill him. We listen to his music, we listen to his station. We can’t live without it.” But word got out and he never came out again, he stayed hidden for decades. I hunted him down and got him out for one show to come see the E Street Band and I met him and thanked him. He’s gone now but — quite a hero.

Who of all the artists you’ve featured on the show have been the most revelatory?

What I loved is, it was one of those if you build it, they will come sort of a things. It just kept growing and growing. Once you play the band on the radio, without any exception, the next record was always better because now they’re hearing themselves, and it really, really does put electricity into the evolutionary process. My favorite story is a group called — it’s a very funny name –- they’re called Death by Unga Bunga.

That’s from a great old joke!

Yes. When they first came, they were a favor to one of our bands, The Cocktail Slippers was one of the first bands we played, well the first band we signed to our record company. One of them said, “Just do me a favor, give them a listen.” They were just okay, just good enough to play because I have pretty high standards, but good enough to play.

I played them and then, the next track it went better. The next track, it went better. The last record, it’s fantastic. You see that growth and you think, “We are actually accomplishing something here. You’re seeing the evolution of artists letting themselves grow as they hear themselves on the radio.”

Very few have broken through because it’s impossible to break bands now. The only ones that really broke through that we discovered were The Hives and The White Stripes. The Hives we played before they were even on the American label.

We work extensively in Scandinavia, so we had, I don’t know how many, at least 15, 16, maybe 20 bands from Scandinavia we were playing on the show. They’re amazing because they grow up with subtitles, which changes the entire culture as opposed to most of Europe, which dubs their own language in. When you grow up with subtitles, they’re speaking perfectly good English by age 10. They’re so into Americana. I’d hang out with the Hives early on and they’re not even from Stockholm. They’re from way up north by the Arctic Circle.

I really love Scandinavian crime fiction. Have you read it?

Yes. Jo Nesbø’s a friend of mine. I was fighting to get a film incentive in Scandinavia, which didn’t exist in Norway. The way I finally got it done was Jo Nesbø, who had resisted selling his books to make movies for years, finally decided that one would be a movie, so I went to the Prime Minister and the Cultural Minister, I said, “If you let Jo Nesbø make his first movie in fucking Iceland or wherever, you’ll be run out of town on a fucking rail.”

All of his books are all about Norway. They relented and we actually got a film incentive.

For Lilyhammer?

No, no, no. I never got one for Lilyhammer. They never gave us a fucking penny for Lilyhammer! Which was amazing because they spend millions and millions of dollars trying to export Norwegian culture and they’ve never succeeded before we go with Lilyhammer and I took it to 130 countries.

I saw the Born To Run tour in 1975 at the Palladium, on 14th Street in New York City. In the middle of the show, Springsteen suddenly ran to the front of the stage and said: “Stop the music, stop the music! There’s a bomb in the theater!” I don’t know if you remember this.

Oh, another bomb threat?

Buy this book now!

Everybody was freaking out because at the time the Puerto Rican Liberation Army were blowing up places in New York. Then he goes, “No, I’m just kidding!” and launched into a new song.

Well, we had one on that tour. We had a very famous bomb threat in Milwaukee. In those days, Columbia [their record label] had a party in every single town. It was amazing, what a different business it was. Now, you can do a two-year tour and if you see them once, it’s a miracle.

So they had to empty the theater. We thought, “Well, let’s have the party now.” So we went to a party and got completely fucking loaded. It was the drunkest I’ve ever seen Bruce in public. They were taking him back to the show and we were very back to our bar band days. We started the show with Little Queenie, a Chuck Berry song — that was one of our best shows ever.

Can you imagine the outrage now? They’d have arrested everyone at the Palladium! At the time, it was like, “Oh, okay, good. No bomb, hurray.” Did you guys know then you were going to get as big as you did?

No, you never know that, but we knew we were good, though, because we’d been around — we’d actually been around a long time. We probably put more time in before making it than any other band, I think, in the business. The Beatles were probably second, they did a good three, four, five years before they broke through. We were playing since ’65 and didn’t get noticed until ’74. Didn’t have a hit till 1980, which was 15 years later. We spent some time. We were very, very good. That’s what blew people’s minds.

Bruce was on the cover of Time and Newsweek in the same week. It became a thing where, “Oh this must be hype.” It must be something invented by the music business. Everybody came to scoff, they came to put us down. Then we just blew their minds. We were just that good.

Hype was a bad word in those days. You weren’t supposed to have a hit single. I know people find this hard to believe but having a hit single was not cool. You had to have it at the right time. It had to happen to the right hit singles. By the end of the ’60s and the ’70s singles were not cool. It was a whole different sensibility. I think Led Zeppelin put it into their contract that they couldn’t release a single. The Beatles of course, kings of pop for real, did not release a single from Sergeant Pepper. You got to make a statement that it’s album time, folks.

By being a bar band in those days you were dance bands, you had to make people dance or you didn’t work. It was the same thing for The Stones, same for The Who. That’s why when it turned into concerts, they had that extra energy of getting people up to dance.

We carried that into the concert world. The same thing with The Stones, The Who, Yardbirds. It was all the same, Dave Clark Five, the same thing. You were dance bands in those days. Well, yes, people danced to rock and roll which I know people can’t imagine now.

To answer your question. We couldn’t have known we were going to be that big. When we finally had a hit with our fifth album The River, “Hungry Heart,” we went from, I don’t know what, selling 600,000 albums to 3 million and started selling out arenas. I thought that surely is as big as you can be. That was enormous. We were filling out arenas. At that point you’re rich really by any measure. You thought, “That is as big as you can possibly be.” We would not have even imagined just another 20 million after that. Only a few people play stadiums after the Beatles, which I think probably was the first.

Why did you leave Springsteen?

I just got obsessed with politics at that point. I just — you worked your whole life to get to be a success and then suddenly you are a success. The tunnel-vision that you have fades away and I started thinking, “Jesus, I wondered what I missed in the last 10 years?” You start reading books and you start educating yourself a bit. Before you know it, a little Chomsky here and there and you’re suddenly saying, “Wait a minute, I’m growing up in Nazi Germany, I got to learn something about this!” [chuckles].

It was all very hidden in those days. Unlike now, which is the biggest difference politically. Everything that Reagan was doing was very, very hidden. I felt it was my obligation as a citizen to start saying something about it. So I left. Looking back of course, it’s probably the biggest regret of my life. Although, let’s say that some good things came of it. I got engaged with the South Africa issues. With Biko, Mandela, we did all that. The results have been important.

Now, I’m not sure it would have happened if I’d stayed. Plus my own work, which I came to being an artist pretty late in life. I was writing songs for the South Side Jukes. If I hadn’t left [the E Street Band], I’m afraid I wouldn’t have made a solo album. I didn’t have that kind of ambition.

You look back with regret and I wish I could have done all of those things and stayed in the band. That would have been the perfect solution.

What did you miss while not being with the band?

Well, I got very busy, went very deep into researching my political records. While they’re playing stadiums I’m hiding in the back seat sneaking into Soweto to talk to the Azanian People’s Organization. Which was the most violent of the black groups of revolutionaries. [Chuckles]

I didn’t have time for really too much regret. I was just very, very busy in those days doing that whole Sun City Project.

In the end, like I say, the life I’d been working towards for 15 years and I just threw it away. I was foolish when I think about it now. It’s hard to measure what would’ve happened, what wouldn’t have happened.

I always think when I hear people say, “I have no regrets,” that’s bullshit. You have to have regrets. You haven’t lived if you don’t.

That is true. That was a big one. That really was a life-changer, a game-changer. That’s when everybody got rich. After that, all my projects would have some form of financial struggle. My first solo band alone — taking an 11-piece band around the world.

I rejoined the band after 18 years. In ’99, but it was an 18-year hiatus.

How have the last few years been for you?

I think, at this point, these last four years have been the most productive of my entire life. It’s a lot to happen at this stage of the game. It’s really quite satisfying. The Lillyhammer score, which I’d done. The live box set and the other box set of the catalogue. Then The Summer of Sorcery box that came out. I did five album packages in three years. That’s pretty good.

Bruce Resnikoff and Universal have my complete gratitude for being so encouraging. I never would’ve done it without them.

What’s your favorite album and favorite song of yours?

Well, these things change day to day, month to month. I think, in some ways, my Born Again Savage album, which was my fifth and my last in the ‘80s, because it’s one of the very few rock albums I’ve ever done, probably the only real rock record I’ve ever released. It’s like a ‘60s hard rock record. I did it because Adam [Clayton] from U2, I happened to be talking to him one night and he was like, “What are you doing?”

I said, “Well, I got a bunch of songs and I don’t know what to do with it, man.” So he was like, “Let’s go in and record them.” Because it was a hard rock record, we got John Bonham’s son Jason on drums, and Adam on bass, and really this is the only album I’d ever played a lot of guitar on because most of my records have always been a combination of soul and rock and various things. I’d never made a straight-ahead rock record until then. I’m kind of proud of that one. The songs are some dystopian-type sci-fi songs on there and some really extended versions of things that were very, very cinematic.

Probably “Time of Your Life” is [my favorite song]. I wrote it for a Chris Columbus movie. It turned out to be really my whole philosophy of life in that one song.

I thought you were going to say “Sun City.”

Well, that certainly did the job. I do these Master Classes for songwriting, and I say, “Write with purpose.” I’m like, “By the way, live with purpose.” Certainly write with purpose. When you’re writing a song like that, the purpose of which is to get the entire country motivated towards an issue — it’s certainly turned out to be a good one. That would also be one my favorites.

What’s your favorite cover of one of your songs by another artist, and what the hell did Nancy Sinatra cover? I’m not mocking her, it just seems like, wow, what an interesting outlier!

Yes. Well, she’s a friend.

The first was always the most exciting, I guess. It was funny because I’m coming out with my second album, Voice of America and I asked the record company guys, do they have a deal in Jamaica? They said, “No, not really.” I said, “Would you mind if I sent it to a friend of mine, Chris Blackwell? Maybe he’d put it out.” They were like, “Fine, go ahead.” I sent it to Chris Blackwell, the song “Solidarity”, which was one of the two reggae songs on Voice of America. I didn’t hear back from him. The next I hear it is when Black Uhuru comes out with it.

That’s so Blackwell — “I’ll have that. That’s mine.”

It was quite a big hit for them. They won a Grammy with it and everything. I was actually thrilled about it. That was a very big moment, the first time somebody covers your song. Then from the same album, Jackson Browne does “Voice of America”, the title track, and then goes on to also do “I’m a Patriot”, the other reggae song on the record. Kris Kristofferson did that song.

Nancy does “Baby Please Don’t Go“. It was the B side of the Ronnie Spector and E Street Band single, “Say Goodbye to Hollywood,” which was a Billy Joel song. Nancy did it a couple of decades later.

I just love her. She was at my festival in 2004. We had an Underground Garage festival. At the time my wife had an underground garage girls go-go group. Then when Nancy did “These Boots Are Made for Walking,” Maureen had 60 go-go girls on stage with her.

What have you wanted to do musically that you haven’t yet?

What I enjoy doing most I never do. Which is I love producing big shows. I did The Rascals show on Broadway, Once Upon a Dream, which was kind of a hybrid show between a rock concert and a Broadway show.

First of all, I reunited them, which was impossible. We reunited them briefly. In between songs, the stage would go dark and on the screen they would talk about their career and the songs. It was really quite a big production. I really loved doing that.

I wish I had studied more choreography and things like that. You never quite get there, but that’s what I would like to have done.

What groups or musicians have you deeply admired? The special ones.

Well there really is quite a few, but the most impressive? If you take the cream of the cream of the cream of the cream of the crop, Jimi Hendrix comes to mind, the great tragic loss of losing him so early. Because he really, literally was completely unique. To be that completely unique? We’ve never seen the likes of that before or since. You really got to wonder where the heck he would have gone. The other real genius I think was Prince. I really miss him, a great tragedy also. Just the single most talented guy ever I think.

Jimi Hendrix just slightly above in the sense of being so completely original but Prince was absolutely magnificent. Did the greatest live show I’ve ever seen, when he did the Sign of the Times show, which unfortunately didn’t come to America. He was in Europe. I was touring Europe at the time so I ran in to him quite often and I saw the show three times and it was the most amazing live rock show ever.

The entire stage would change before your eyes. They filmed it, which I’m glad so people could get a glance at it. But it’s not quite the same thing on film. Because you’re used to things changing on film, you can edit stuff from here to there, it’s not that remarkable, but when you see it live transform itself? He had interstitial music in between the songs.

A lot of acting going on. It was just the greatest show I’ve ever seen. I think Jimi Hendrix and Prince have a special place. The Beatles, The Stones and The Who and the Kinks and the Byrds. They set high standards and of course Bob Dylan. That ’64, ’65 period set my standards forever and really saved my life, I can’t imagine where I would have been without them.

You once said that but for music you would have wound up in a real mob like the Sopranos. Was that remotely possible?

[Laughs] No, I’m mostly joking about that. I was in a suburb so it would have been unlikely actually. Mob stuff is an urban thing for the most part. You never know, I’m not big on following rules. It was a little bit of that in me. That anti-authoritarian rebelliousness that I think that makes criminals who they are [Chuckles]. Give me the criminals of rock n roll, man.

I actually wrote a song for Michael Monroe called, “Dead, Jail or Rock ‘n Roll.”

There’s definitely a parity between Rock ‘n Roll and crime, absolutely. There’s the white and the black.

Yes, because you’re just making up your own rules as you go.

How did you become an actor and wind up in the Sopranos?

It was one of those Hollywood stories I wouldn’t believe if it hadn’t happened to me. I wound up in the Rascals in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the first time it was ever televised. They used to just do a private ceremony. David Chase happened to be clicking around and stopped on that channel. He heard my introduction speech. He was an E Street Band fan. He happened to have my single out at the time as well. He was a music fan but when he saw my speech, which really was a comedy thing — it’s probably on YouTube somewhere — he said, “Let’s get him in the show.”

I had nothing else to do because at that point I was blackballed from the business a bit. After “Sun City”, they didn’t want to know me because it was a little too successful. You can feed people in Africa, but you start bringing governments down? Makes people nervous. [Laughs]

So I wasn’t doing work much in the business anymore. I said, “Well, I’ll try acting, what the hell, yes.”

You’re brilliant, actually. Obviously everyone tells you that.

I was very, very lucky, but again, nothing but gratitude for David Chase and to Jimmy Gandolfini, and then the rest of the actors who treated me so well. They could very easily have had an attitude that, “Who the fuck is this kid coming in here? This fucking hippy guitar player all of a sudden thinks he can act?” They did none of that. I think Jimmy, he set the tone, really through the whole set. He was just immediately very friendly and acted as a mentor to me. It was wonderful, and I took everything I learned and took it to Lillyhammer and went from new craft to five. I ended up co-producing that show and co-writing it and did the music for it and directed the final episode.

In the early days of Netflix you could literally see all they streamed. They had maybe a hundred shows. So you’d go through the whole thing and go, “This Lillyhammer thing, that’s look good.”

We were the first [original] show. We did three seasons, eight shows in the season. It was only 24 shows.

People were just waiting and waiting for a new season — I’m still waiting, Steve.

Yes, I know. I get that all the time.

It was such a great show.

People discover it all the time. It turns people into fanatics, because it’s such a weird show. Let’s face it. With all of the police shows on, they’re very predictable plots. You just couldn’t tell where this show would go. There was a husband and wife that created the show. Brilliant Norwegian writers. I couldn’t resist doing a show in a foreign country.

I had to take a chance. Everybody said, “You’re coming from the biggest show on TV and making history to some local show in Norway? Are you out of your fucking mind?” I was just like, “No. The whole thing, I’m one of the producers, and one of the writers, I’ve never had that much control.”

I had two brothers in the thing. My middle brother was the hitman, and my older brother was Tony Surico, the priest.

How did it come about?

One of the Norwegian bands I was mixing in Bergen, which is the west coast of Norway, said there’s this writer husband and wife in the lobby, “you want to say hello?” I go down and meet them. They say, “Listen, we’ve written a show for you.” And you don’t get that one every day.

You don’t. I do, but you don’t.

I said, “What?” Well, the one sentence pitch was, he actually goes into witness protection in Lilyhammer, Norway.” I was like, “Oh man, I just played a gangster for 10 years. I really shouldn’t do this.”

I just couldn’t resist in the end. I was like, “He’s going to look the same, but it’s going to be quite a different character.” I had had to be a bit reserved, watching Tony Soprano’s back. Whereas this guy, he really is a born leader, he’s born a boss, he’s crazy. And the circumstances are so crazy, because he’s dropping a one man crime wave into a place where there’s no crime. I was like, “I can’t resist this, I just can’t.” It was the biggest hit in Norway, in Norway’s history by far, and we sold it to 130 countries.

Then the big TV show in Monte Carlo, the International TV Awards, we won best show two years in a row, which is very, very rare.

What’s the best thing about being a rock star and what’s the worst? That you can say?

[Laughs] First of all, you doing something you love, we should never ever take that for granted. I don’t care what you do in life, if you doing something you love, you have made it. Start with that. Our particular business, and that’s true for the entire entertainment business, you bring people joy. You try to bring a bit of insight here and there, a bit of education when you can, or motivation and inspiration. Basically, your job is you’re bringing joy.

If you can add to that, which is turning people on to things and giving them ideas like I was turned onto Eastern religion by George Harrison, and Allen Ginsberg, who you introduced me to, which is one of my favorite moments of my life, in your house.

I’m also kind of lucky because it’s one of those things that might be a thing of the past, let’s face it. There’s always going to be successful people to some degree but that kind of success that we had, we may not see again.

It’s a moment in time I’m lucky to be a part of, which was the end result of what I call the Renaissance, which is the ’50s or ’60s, when the greatest art being made was also the most commercial. When that’s happening, you’ve been in the Renaissance.

Is there a worst aspect of being a rock star?

Yes. If you get too big. There’s one moment in my life, and different people are going to react differently, but I’m not naturally a guy who likes the spotlight, I’m more or a behind-the-scenes kind of guy. I got used to being a front man, and I got good at it. But there was one moment in time when I had two hit singles in Italy. I had come over, we’re going to go shopping and look around Rome. We couldn’t walk down the street, because it had got so popular and I thought to myself, “I really don’t like this.”

Some people would be very happy about that, a bit naturally. I really didn’t like it and thought, “This is actually not where I want to be.” I’d like to live, not stay hiding in fucking hotel rooms. I want to live and want to be able to observe people and observe life because you’re learning about it. I think there are bigger problems in life, obviously, than being too famous. We shouldn’t put too fine a point on this, but I think there was that uncomfortable possibility that you could get so isolated.

What’s the proudest moment of your life?

Probably seeing Mandela walk out of jail. I think that was a moment I never thought I’d see. I was really, really, really moved by that because it was a bit of a surprise. Even though we had laid the groundwork and done everything right, it just was something that we thought was never going to happen. That’s probably number one.

I think my school curriculum, this is going to be a close second, because the teachrock.org, it’s about 40,000 teachers. Right before the quarantine, the day before the quarantine, I went and visited a partner school of ours because we were starting to have not just teachers teaching the curriculum, but entire schools. There’s one school in the south of L.A., from kindergarten to 6th grade, integrated our curriculum into every single class.

Basically, our thing is integrating the arts into the education process, simple as that. Every class has our artistic dimension to it. I swear to God, I really haven’t had an out-of-body experience, but I’d been working on this thing for 16 fucking years. Seeing it actually functioning and the happiness and joy with these kids and the teachers, all having just nothing but fun. They’re using all of our curriculum. Very, very, very exciting.

That and the opening night of The Rascals Once Upon a Dream was extremely meaningful also, I really understood the whole theatre thing in that moment.

I’ve had my moments.

Last question. What’s the secret to a successful marriage?

[Laughs] I get this all the time and I half-jokingly say, the secret of being together is to stay apart. [Laughs] And I mean that.

I’m half joking but you need to have your own space. I think each of you need to develop your own lives on your own. You come together and it keeps it new, keeps it fresh. You talk about whatever you’re doing. I think those things are essential. If not, I see so often that one plus one can equal one and a half. Rather than one plus one equaling three which is what you hope for. I think it’s very important that each of you has your own identity and your own lives.

Leave a comment