Too often living legends go neglected in their own environs, as if already past history. They become walking ghosts, barely acknowledged where they exist–while neighbors thrive off their genius.

Austin, Texas is in the middle of its first post-pandemic, in person, somewhat subdued (1,400 bands instead of 2,000) South by Southwest (SXSW) music, film, new media, everything-but-animal-husbandry festival. This bloated, expensive (ten-day access badge: $1,395 to $1,895) schmooze fest is the tech-elitists’ successor to the old-style Texas State Fair (which still takes place in September in Dallas, 24-day pass $50).

This year’s SXSW is still expected to draw, incredibly, hundreds of thousands of attendees, in the process generating enough income from ticket and gear sales and big buck sponsorships to pay for two floors of offices in Downtown Austin in the eponymous SXSW Center, 13 stories of undulating glass and stolid Stalinist gray pediment “created to be a physical manifestation of everything SXSW and Austin has to offer.”

If that means the ultimate commercialization of alternate pop culture, they’ve succeeded. But for all their financial gains, you’d think they would toss a few chips toward Jim Franklin, the man who made Austin weird over 50 years ago. Without him, SXSW might not have been possible.

“Jim was an inspiration for Austin culture in general,” admitted Nick Barbaro, who co-founded the first South By Southwest (name inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s movie “North by Northwest”) with three other locals in 1987. In a canned statement to SPIN, Barbaro continued: “SXSW was very much about Austin culture. It wasn’t conscious, but [Jim Franklin] was a very influential and inspirational figure when we started SXSW.”

And that’s why Jim Franklin has never been featured on a program nor paid a dime, because he’s just down the road and now easily ignored at age 78? Nick Barbaro was not available for further comment.

Sadly, SXSW has never acknowledged Jim Franklin or respected him with so much as an invitation to this most popular of local extravaganzas, out-drawing anything but major sports events in the Lone Star State. Do a search on the name Franklin on SXSW’s site and you’ll only find references to Aaron Franklin, the non-related owner of the meh BBQ joint in Austin non-natives drool over (for the real deal, try The Salt Lick outside of town).

“I’ve never been invited,” says iconic drawing, painting, musical performing artist Jim Franklin. “But I haven’t sought it out, either. I’m not interested in what’s trendy. I do what I do because it’s what I need to do.”

With his bald pate and long hair in back, he vaguely resembles another Franklin, polymath Benjamin of Colonial and Revolutionary times. “Somewhere up on my family tree, we’re one step away from Ben Franklin,” Jim explains. More importantly, one of his ancestors fought at the Battle of San Jacinto, the decisive event that led to Texas’ independence from Mexico. “He may have guarded General Santa Anna after he was captured,” Franklin adds. That bit of lore makes this otherworldly artist as native as they come in these parts.

So who is Jim Franklin and how weird can he be to have branded a memorable music and cultural scene in the heart of Texas?

Start with the budding artist growing up in Galveston, Texas, gaining acclaim in first grade for his drawing of a horse’s hindquarters. After obligatory art studies in San Francisco and New York (with a brief but uncanny connection to Salvador Dali, patron saint of surrealism) he moved back to Texas and found its oasis for unconventional creators, Austin.

This exotic undulating patch of green amid arid flats was named after Stephen F. Austin, who brought American immigrants from Missouri to the future Republic of Texas – and perpetuated slavery within abolitionist Mexican lands. Out of such contradictions grew a state capital and its world-class educational institution, the University of Texas (UT Austin).

While many UT Austin students came in from around the state and moved back out after graduation, the misfits and oddballs lingered. Ample acid, bales of wacky weed, coltish young men and hot, ornery women turned this crossroads into a cradle of hippie, stoner creativity. Psychedelics, art, music, writing, film, and early multimedia all made for a unique, heady cultural mix.

But how to symbolize it? That’s when Jim Franklin found his theme, Dasypus novemcinctus, the nine-banded armadillo. Native to central Texas, this ancient mammal in a reptilian body is often found as roadkill along the highway. Its coat looks like a leather shell, but is a carapace of the same stuff as hair, matted into articulated armor — hence the Spanish name: armadillo, little armored one.

“As a kid I was attracted to armadillos.” Franklin recalls. “They’re prehistoric remnants. How often do you see dinosaurs walking around?” Franklin would grow into a dedicated surrealist artist, working with mind-bending themes. He didn’t care for Disney-esque cute animals, preferring hard-edged critters in their native environment. “Armadillos are surreal. Everything about Austin was surreal. When people saw my work, they’d go ‘Jim, that’s weird.’ Soon they were saying ‘Austin is weird.’”

For this artist’s visions when Austin was truly weird, visit Jim Franklin Studios’ home page: At the top is his first armadillo cartoon, drawn for a community fund-raising rock concert and “Love In” in 1968, with a tokin’, clawed wonder and his stash. And there’s the 1973 poster for another Austin milestone, Willie Nelson’s first 4th of July Picnic — led off by a Lone Star flag-waving armadillo.

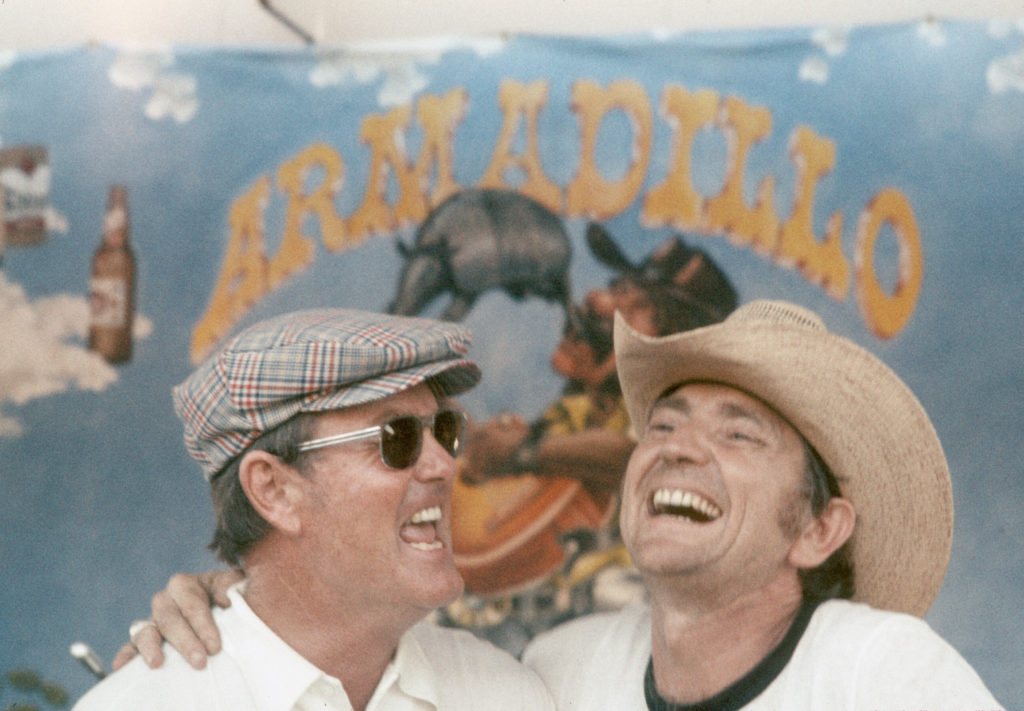

In between, Jim Franklin became a mainstay of the Armadillo World Headquarters, an aging National Guard armory turned widely-heralded concert venue. For a few years prior, Franklin had been the live-in weirdmeister and poster designer for Austin’s original psychedelic music hall, the Vulcan Gas Company. Located on a busy avenue, attracting students and others to linger outside inhaling the music and controlled substances, it ran afoul of local authorities. Within three months of its closing, the Vulcan was replaced by an even odder venue on the other side of a bridge known for its hanging bats -– the winged kind.

Credit for founding the new center for head music (and blues and jazz and occasional ballet) is usually shared by Eddie Wilson, the manager of local group Shiva’s Headband, with start-up money from the group’s signing to Capitol Records; plus Mike Tolleson, a prominent Texas attorney, and Bobby Hedderman, one of the principals at the Vulcan, with added investment from the father of of the founder of Shiva’s Headband and Mad Dog, Inc. and a bunch of local literati including sports journalist and screenwriter Bud Shrake. And of course, Jim Franklin.

From 1970 to 1980, the echo-y, dirt-cheap, marihuanero Mecca often simply referred to as the ‘Dillo, hosted performances by cosmic cowboys and country rockers, becoming the home stage for alt-C&W musicians Michael Martin Murphy, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Asleep At The Wheel. Legendary live albums recorded here included kick-ass performances by Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, Freddy Fender, Freddie King, Frank Zappa, and Doug Sahm’s Sir Douglas Quintet. As notable were jam sessions by unexpected combos of music stars, like Jerry Garcia, Leon Russell, Doug Sahm and friends on Thanksgiving 1972.

[embedded content][embedded content]

With clouds of pot smoke confined to its spacious interior and fenced-in outdoor beer garden, Armadillo World Headquarters was never raided by the police. Rumor had it that the lawmen didn’t want to have to bust fellow officers and prominent politicians. (Requests for comment by current Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who attended UT Austin from 1977 to 1981 and must have, surely, taken in shows and imbibed cold brews at the beer garden at the ‘Dillo, went unanswered.)

In addition to being the Armadillo’s literal artist-in-residence (painting and living in a sunny space on the second floor), Jim Franklin MC’ed and performed at the concerts, a major attraction in his own right. “Creative lunacy” is how John Wheat describes it. In Austin they say if you can remember going to the ‘Dillo you probably were never there, but Wheat is a credible witness, having attended mostly jazz concerts and appearing once on stage as a drummer for a Brazilian Carnival celebration. “You never knew what Jim Franklin was going to do,” he says. Wheat got to meet JFKLN, as the artist signed his work, in 1984, when his poster art was added to the archive collection of UT’s Briscoe Center for American History, where Wheat is currently Coordinator for Sound Archives.

Offstage, Franklin was the Austin culture’s most visible promoter, first with his concert posters — which oddly never became as collectible as the ones for East and West Coast shows, at venues like the Fillmore. Ardently anti-commercial when working on his own art, he enjoyed plugging bands’ concerts. “Music is art,” he notes. “I like my art getting people to listen to music they wouldn’t hear otherwise.”

When Franklin alone couldn’t produce the sheer volume of artworks needed to plug the increasing number of shows, other artists stepped in, ultimately becoming known as the Armadillo Art Squad. A nostalgic look at the Squad’s varied come-ons for memorable concerts can be found in a video posted by the Austin History Society, the local history division of the Austin Public Library: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tlBV7ZvYGUE

After an itinerant New York journalist came through town marveling at the scene Franklin had nurtured and championed, the Armadillo Man became Austin’s de facto ambassador to the national media, welcomed to sit in with a bunch of independent journalists in midtown Manhattan to spread the word. Soon The New Yorker ran a profile of Franklin, which read as if author Hendrik Hertzberg simply turned on a tape recorder to capture the artist’s words.

Through dumb luck or bad timing, the next milestone on Austin’s path to weirdness was not captured by Franklin. A seemingly washed-up Nashville singer-songwriters’ singer-songwriter, who had left Muzak City for the wide-open spaces of his native Texas, Willie Nelson made his debut at the Armadillo World Headquarters on August 12, 1972. He played on until dawn on the 13th at an afterparty sponsored by writers and poets and — this is Texas — UT football coach Darrell Royal.

One of his hosts in the wee hours would later co-author the first of Willie’s autobiographies. Willie recalled about that historic night in his book with Bud Shrake: “Rednecks and hippies who had thought they were natural enemies began mixing without too much bloodshed. They discovered they both liked good music,” Nelson would soon invite his fellow Country & Western mavericks Waylon, Kris, and Johnny Cash to play the ‘Dillo. Outlaw Country was born.

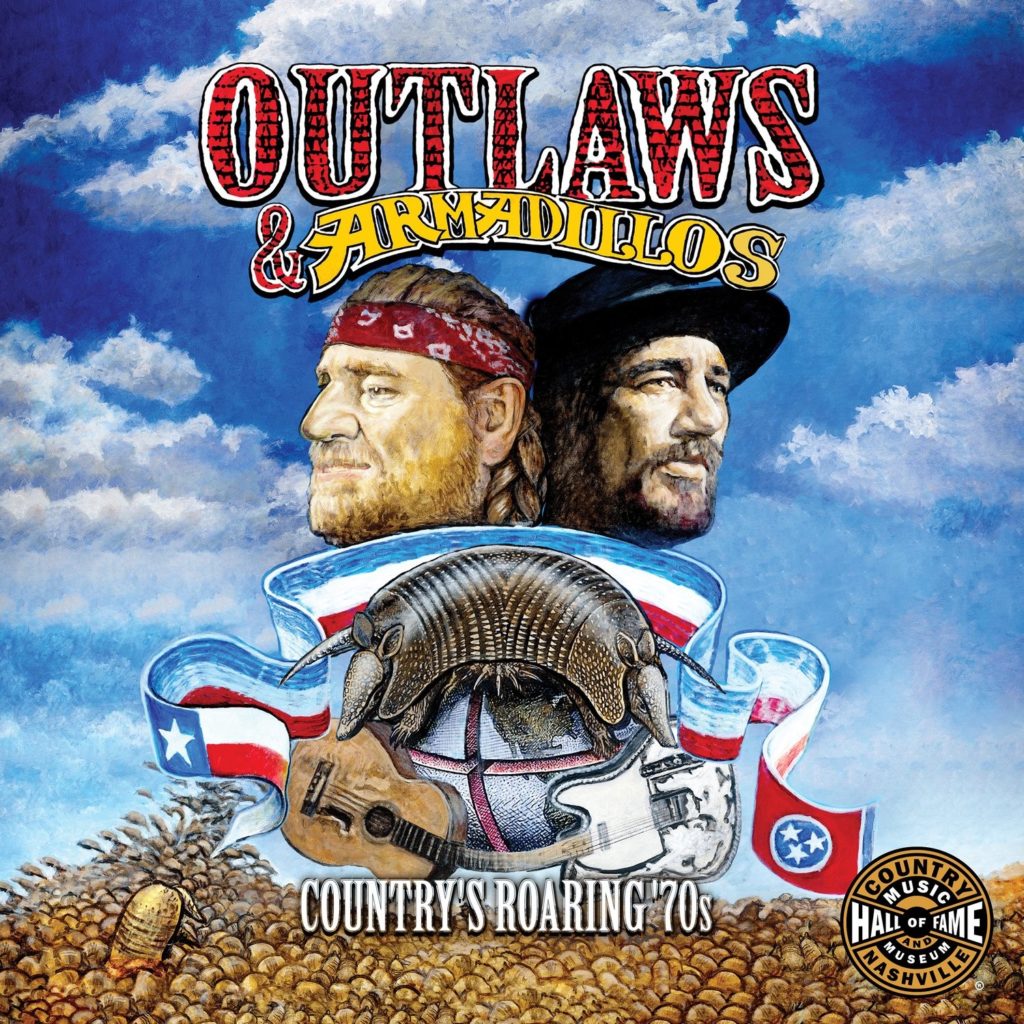

Franklin befriended Nelson. Known for his unique album covers for the likes of Freddie King and Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, Franklin nonetheless was never asked to do cover art for Willie, perhaps a sign of the impending break-up between Nelson and the Armadillo World HQ, punctuated by Willie and his business people grabbing away the coveted site for what would become Nelson’s Texas Opry House. Franklin’s sole cover art portraying Nelson was for a song compilation issued to accompany the Nashville-based Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s 2018 exhibition, Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s. The two CD set happens to be the best round-up of ‘Dillo music to be found anywhere.

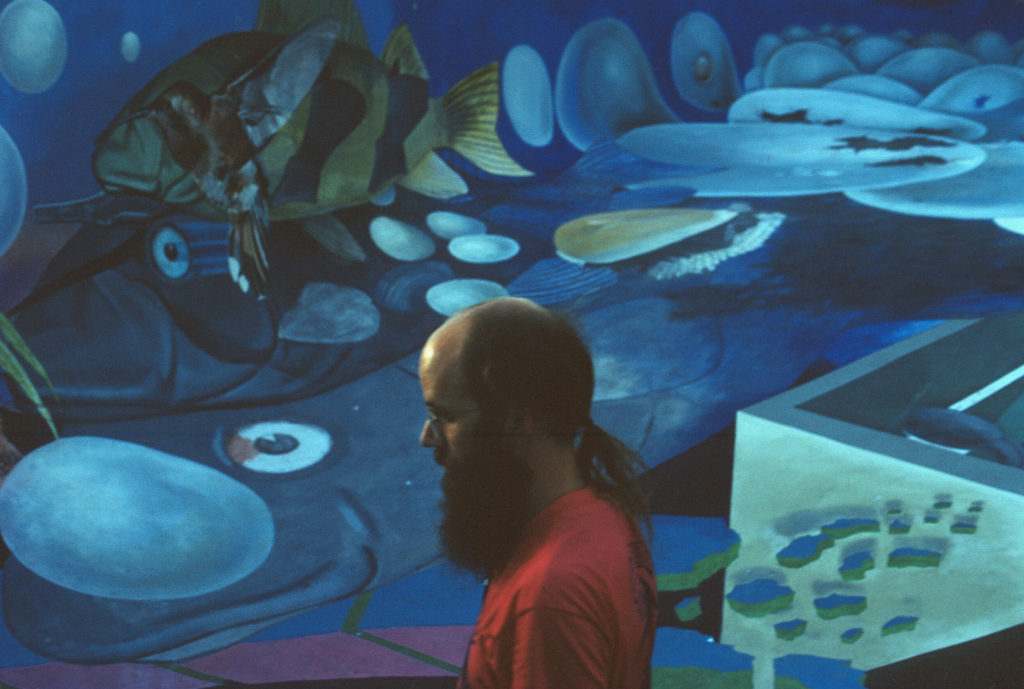

About the time Austin was at its weirdest in the early ‘70s, Jim Franklin’s sensibility was in keen demand. He was even commissioned to paint piano-rocker Leon Russell’s home swimming pool, across the border in Tulsa, OK.

Undersea creatures had been subjects for surrealism since Salvador Dalí’s “Lobster Telephone.” Franklin got to paint them bigger and bolder on a curved pool surface. The creation of this unique art piece was chronicled by award-winning documentary filmmaker Les Blank, known for his deep dives into American regional musical styles and the cultures they grew out of. But the movie, commissioned by Russell and his music producer Denny Cordell, went unfinished for over forty years, because Leon found it spent too much time on Jim and not on him. It was finally completed by Blank’s son Harrod, and released in 2015 titled “A Poem is a Naked Person,” after a Bob Dylan lyric.

It should have been an omen when Franklin, who had never been good with money nor ever had competent management, completed his artwork and asked for his fee. While working, he’d been housed in Russell’s home and given an account at the paint store for supplies, only to learn that he wasn’t getting one cent more: “You’re trading art for art,” he was told by Leon, as if that justified screwing him out of his pay. Like so many rock stars spending beyond their means, Leon Russell was soon tapped out. His house was sold off to real estate developers. Franklin’s magnum sea opus would be covered over with gravel and dirt. When uncovered years later, it couldn’t be restored.

Meanwhile the Armadillo World HQ was being mythologized but also suffering money problems. Songs were being written about the Austin scene, including probably the best one ever: “London Homesick Blues” with the refrain “I want to go home to the Armadillo / Good country music from Amarillo to Abilene. / The friendliest people and the prettiest women

you’ve ever seen.” (It was reprised by composer Gary P. Nunn and Jerry Jeff Walker in 1991. ) The Armadillo wasn’t going to be anyone’s home for much longer.

Already hanging by a thread financially, the Armadillo World Headquarters filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1977, surviving on fumes and the goodwill of its staff. After missing two-thirds of their paychecks over the winter, none of the tenuously employed crew quit their jobs, subsisting on beans and bread to keep the ‘Dillo going. There were still some notable, unexpected gigs like a classic performance by Talking Heads in 1979, fortunately well recorded and preserved online.

Ultimately the Armadillo was done in by the popularity of the beckoning local environment it created. By the start of the extravagant Eighties, the cheap comforts of Austin were fading fast. The famed music site was worth more razed to make room for new construction. Where local psychedelic rock band 13th Floor Elevators had played would stand another 13-floor, bland layer-cake office building, One Texas Center.

The Armadillo’s end came in spectacular fashion, with a New Year’s Eve concert kicking off 1981. The headliners included Asleep At The Wheel, the neo-Texas Swing band led by copper-bearded scraggly haired giant Ray Benson.

[embedded content][embedded content]

In 2022, a silver-bearded Benson, soon to be 71, reminisces about the Armadillo and Franklin’s originality. “I remember Jim’s Pumpkin Stomp on Halloween 1978. Asleep at Wheel was playing while Jim stomped a pumpkin in his cowboy boots. It was so strange and so cool.” Benson relishes memories of the ‘Dillo as the place bands like his could perfect their skills in front of sympathetic audiences. “We could learn from our mistakes; the musical artists and the visual artists like Jim could take chances and just got better.”

One redeeming side to this year’s SXSW is Benson’s annual Birthday Bash celebration on March 15, a fund-raiser for the local charity he helped found: Health Alliance for Austin Musicians (HAAM), a non-profit dedicated to helping musicians in the “live music capitol” get medical care while they’re often uninsured. Last year the organization helped over one third of Austin’s resident population of musicians -– a need that speaks to the River City’s loss of solidarity and community spirit over the years.

The city’s weird, wonderful humanity evaporated as it nearly tripled in size in the 30 years from the opening of the Armadillo HQ to the turn of the century. In 2000 a caller with a donation to a local weekly radio show declared that his gift was to help keep Austin weird. The need to preserve the city’s unique vibe was echoed by others, but KEEP AUSTIN WEIRD quickly turned into commercial branding for small local enterprises — not one bit weird.

Today with a population of over one million, making it the 10th largest city in the US, Austin is hardly weird. More like Anywhere Techcity USA, encased in anonymous fussy-shaped glass structures dwarfing the distinctive state capitol dome that Franklin once depicted being humped by a giant armadillo.

This is a city without pity, let alone simple decency. Awash with funny money and crypto cash (same difference) and rich refugees from the genteel rigors of Silicon Valley, Austin boasts dozens of art galleries across the sprawling metropolis, yet none represents Jim Franklin, who still owns many of his now historic originals. He’s been living and doing his art -– lately more abstract drawings and paintings, with occasional “ideal architecture” models -– in the smallest space he’s ever occupied. After all the years as a walking embodiment of what made the area a beacon for creativity, he seems abandoned by a sterile technopolis. “I’m not respected artistically or intellectually,” he says, with good reason and resignation.

But help is on the way. In recent days, the owner of the Texas-based Planet K Gifts store chain, Michael Kleinman, has provided Jim Franklin with a large space in which to work. An early transplant to Austin from New York City, Kleinman first met Franklin in 1973 and has been a benefactor over the ensuing decades. He’s also been a local do-gooder for years through his Phogg Phoundation for the Pursuit of Happiness -– weird, for sure! As a countermeasure to the insanity of South by Southwest, Kleinman is planning a post-SXSW pop-up exhibit of some of Franklin’s work in the space reserved for another of Kleinman’s projects, the currently dormant Tex Pop, Museum of Popular Culture.

Not too far off from now, look for a documentary on Franklin and his impact on Austin, one of a series in progress by Harrod Blank — who earlier resurrected his father’s doc on Jim painting Leon Russell’s pool — and director/producer Erica McCarthy on American artists and their home communities. Completing Franklin’s story is the documentarians’ number one priority.

When asked why when the going got rough, he didn’t just pull up stakes to gain well-deserved recognition on the East or West Coasts, Franklin shakes his head. “I’ve had a San Francisco studio. I’ve taken in the New York art scene. Here I’m in the center of the world. Austin is a place of infinite possibilities.”

Leave a comment