This article was originally published in the May 2006 issue of SPIN.

Two years ago, Red Hot Chili Peppers went to Europe to play in front of the largest crowds of their 20-plus-year career. After surviving numerous personnel changes, drug problems, erratic recordings, relationship dramas, and assorted crises that have broken up countless bands, the Peppers have released back-to-back multiplatinum albums–1999’s Californication and 2002’s By the Way. Against all odds, they had reached genuine superstar status and this jaunt saw them headlining three nights at London’s massive Hyde Park. But for Flea–from day one, the bass-playing yin to singer Anthony Kiedis’ yang–these looked like the last shows he would ever perform with the group.

“To tell you the truth, I really didn’t think I’d be here right now doing this,” he says, sprawled barefoot on the floor of a sun-dappled practice room—lined with books and classic punk-rock photos and posters—in his idyllic, rambling Malibu home. “A multitude of things had built up, and it just wasn’t a comfortable time. The band had always been a sanctuary for me-—no matter what was going on in my life, the band was a place where I could just be myself and rock. All of a sudden it didn’t feel like that, and I just thought it was time for me to not do it anymore.”

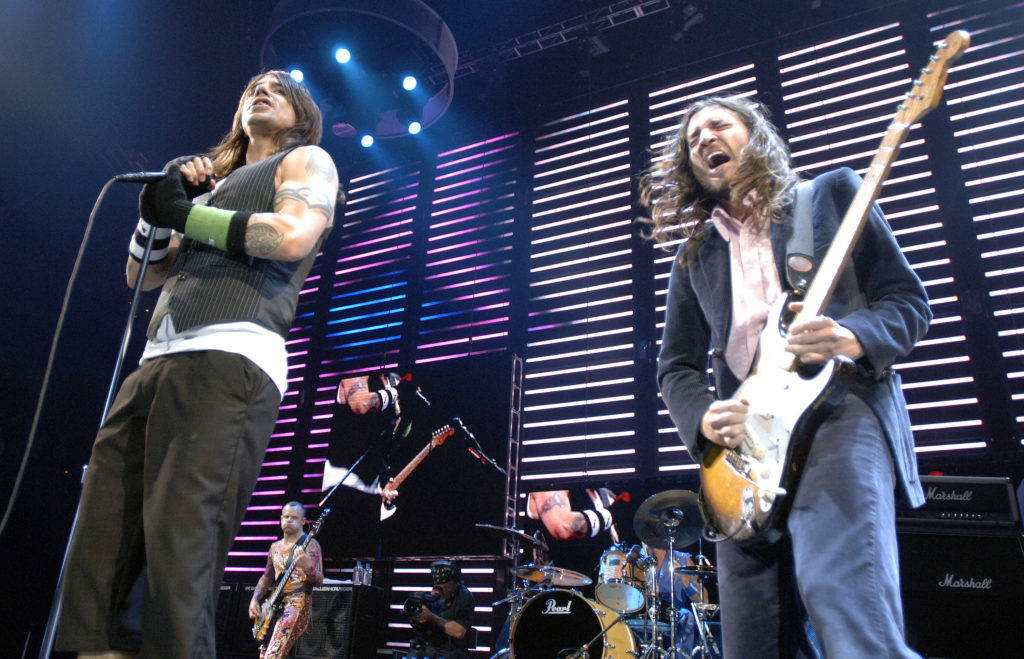

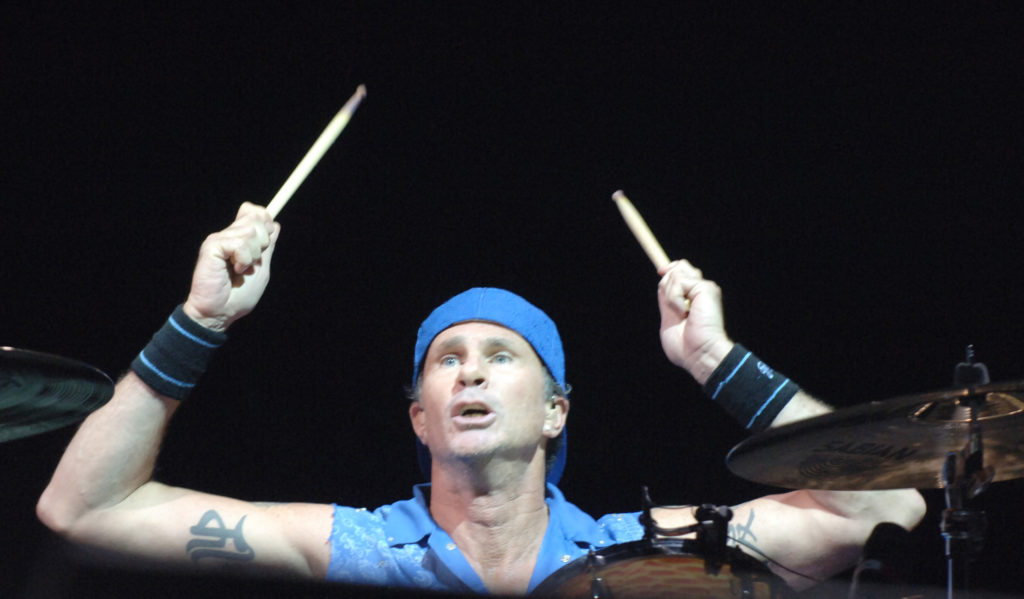

Flea, born Michael Balzary in Australia 43 years ago, is truly the pivot point of the Chili Peppers. With guitarist John Frusciante, he forges the riffs that are the basis of their songs. Alongside drummer Chad Smith, they make up one of rock’s most versatile and powerful rhythm sections, the backbone of the band even at its lowest points. And with his high school friend Kiedis, Flea gives the Chili Peppers a style and soul that has come to symbolize the spirit of latter-day Los Angeles. So while the band has persevered through lineup changes that resemble a game of rock’n’roll musical chairs, Flea’s departure would be serious business indeed.

Eventually, that cloud lifted, the Chili Peppers got back to work, and the result is their ninth studio album, Stadium Arcadium—a 28-song, double-disc set that adds up to some of the the best work of their career. Working once again with longtime producer Rick Rubin, the band returned to the Hollywood house where they recorded their 1991 breakthrough, Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and emerged with a record that mixes old-school Chili Peppers funk with mature melodicism—plus a supersize dose of Frusciante’s flamethrower guitar. From the Zeppelin-esque crunch of “Readymade” to the delicate slink of “Hey,” it’s a power-house statement of purpose, an album that Flea describes as “the sum of everything that we are as a band.”

The making of Stadium Arcadium was as notable as the outcome. During the almost yearlong recording process, this notoriously fractious gang of four were able to put aside their differences, their competitiveness, and cohere better than ever. “This time,” says Kiedis, “those egos—and when I say ‘those egos,’ I mean all of us—were feeling decent and confident, respectful, as excited about the other guys’ stuff as we were about our own. If someone came in with a great chord change for a song or a great rhythm or a great groove, by the time it was finished, everybody had jizzed all over it, and it had become a real community piece of property.”

In John Frusciante’s house in the Hollywood Hills, the living room has one piece of furniture, an L-shaped sectional sofa in front of a purple-painted fireplace. The rest of the space is given over to dozens of guitars, thousands of CDs and LPs, and scattered recording equipment. Sheet music for Charlie Parker’s bebop classic “Ornithology” lies open on the floor. (When I enter Flea’s house a few days later, he’s practicing the same song on his trumpet.) Many of the guitar effects, background vocals, and assorted sonic treatments on Stadium Arcadium were recorded in and around this room. After years of heroin and cocaine addiction, Frusciante, 36, looks clear-eyed and healthy (he runs and meditates every day), and his excitement about the new album is palpable, even overwhelming. Since the previous Chili Peppers record, he’s been unable to slow the music pouring out of him—during the band’s time off, he recorded and released no fewer than seven solo albums, and he brought that cascade of ideas back to this project. “The last few [Chili Peppers) albums had, like, 15 songs, and there were maybe four songs with guitar solos,” says Chad Smith. “This time he solos on pretty much every song. When we go out on tour, it’s gonna be the fuckin’ John Frusciante Rock Show!”

Frusciante certainly operates in his own universe—he casually brings up “that which existed in negative existence” or says, “I just resent going through life having my brain telling me what to do all the time.” Dressed in a black T-shirt that reveals his needle-battered arms, with black sweatpants and olive socks, he acknowledges that it was his all-too-human relationship with Flea that almost torpedoed the band. “By the Way was a tense time for me and Flea together,” he says. “We just weren’t really seeing eye-to-eye, and we weren’t really understanding each other.

“Every time we make a record,” Frusciante continues, “I have sort of a concept, and my concept for By the Way was kind of selfish, because it didn’t have a lot to do with where we would come from. I wasn’t really into doing stuff that was funk based or blues based. Things I would describe as not having that would be the Smiths or Siouxsie and the Banshees or the Cure—I wanted to do something along those lines, and I wasn’t very open to things outside of that framework.”

Flea says it wasn’t the musical direction but rather the attitude Frusciante struck that was so problematic. “I felt that what he was doing didn’t warrant any input from me,” he says. “It’s not like I didn’t like what John was doing, ’cause how could I not like what John’s doing? He’s a great musician. But I didn’t feel welcome to express myself naturally. And once I started having that feeling, I just shut down and kinda withdrew from the process, and it wasn’t a happy feeling.” (After our interview, Flea calls to emphasize that “I don’t blame John for that time I was unhappy in the band. It takes two to tango, and it would break my heart if that’s how it came across.”)

Kiedis notes that creative tension is something of a constant for Red Hot Chili Peppers, which is perhaps predictable for a band of strong personalities whose songs grow almost exclusively out of in-studio jams. “Sometimes there’s a bit of confrontation chemistry, which is good for the creative process,” he says. “Sometimes it’s the dark energy in this band, the mental illness that we all have a touch of, that drives us crazy and makes us hurt inside and makes us have to go bang on something until we find a cool beat. There are a lot of different levels to the chemistry—it’s not like there’s this great sense of constant brotherly love. Sometimes it’s the antagonism that really gets the ball rolling. But it’s a fine line between letting that create rather than destroy.”

After playing the 2004 Hyde Park shows and other huge European festivals, Flea remembers sitting in an airport with Frusciante and “feeling a cloud lift between us.” Right then, he knew he wasn’t leaving the band, and the rabid L.A. Lakers fan (Flea blogs about the team for NBA.com) could get back into the game.

“Did you see that Woody Allen movie Match Point?” Flea asks. “There’s one classic line where this chick is talking about some couple, and she goes, ‘Oh, yeah, they’re really doing great—their neuroses really interlock just perfectly.’

“I think that you can get settled into something, and everyone knows his place, and that’s cool,” he continues. “But if you didn’t go through the emotional pain, it wouldn’t be growing and changing, it’d be staying in one place, and we’d probably be a very boring act. We could have made the same record five times in a row, but to have growth, you gotta go through it. Like (P-Funk leader) George Clinton said, if there weren’t any humps, there wouldn’t be any getting over.”

In November, Flea and his girlfriend, model Frankie Rayder, had a baby girl they named Sunny Bebop. The new parents asked Frusciante to be the godfather.

The recording of Stadium Arcadium took awhile. Smith’s son, Cole, who was born when the sessions started, celebrated his first birthday March 28. (“By the time we go on the road, he’s going to be our tour manager,” says Smith.) An album that was supposed to be a quick-hit, 11- or 12-song blast took on a life of its own. The Chili Peppers ultimately completed 38 songs and considered releasing three separate albums—the 28 songs chosen will be spread over two discs titled “Jupiter” and “Mars.”

“I remember when we were, like, an adolescent band,” says Kiedis, “and I heard that Metallica was going into the studio for a year, and then taking another six months to finish, and I was like, ‘What freaks! What could you possibly do for that long?’ But I get it now.”

What caused the marathon? Credit an unexpected outpouring of material and the ambitions of mad scientist John Frusciante. First came the songs. “It was kind of like Christmas every day,” says Kiedis. “I’d get in the car at the end of rehearsal, and I’d stick in the CD that we’d recorded and be like, ‘Wow, I’m not exactly sure what we’re going to do with this, but I know it’s going to be great.’ Every day it was like that, like one gift after another.”

The Red Hot Chili Peppers’ recording methodology goes something like this: Frusciante, Flea, and Smith jam every day in the studio, working up bits that any one of them might bring in. “We were getting two and three musical ideas a day,” says Smith, “and most of them were pretty consistent, high-quality stuff.” Once those raw grooves take on a more defined shape, they get a title—written down on a whiteboard—and then Kiedis takes them, tries to fit a melody and lyrics, and works with Rick Rubin to construct a real song.

At this point, the affable Smith’s part is basically done; he was finished with this album almost a year ago. Since then, he’s played on other projects, like the new, Rubin-produced Dixie Chicks album and a solo disc by former Deep Purple bassist Glenn Hughes, recorded in Smith’s living room. (Only in the upside-down world of the Chili Peppers would the drummer be the band’s steadiest member. “It’s all relative,” says 44-year-old Smith, “but I’m sort of the normal guy.”)

Meanwhile, Frusciante is adding layers of guitars, effects, and background vocals—and this time, he aimed for the stars. The guitarist rattles off inspirations for his work on Stadium Arcadium—from the Wu-Tang Clan to Electric Light Orchestra, from Jimi Hendrix to…Brandy?!

“I realize she’s not really a hip person to mention because of the TV show or whatever, but I’m crazy about that album Afrodisiac,” Frusciante says with absolute sincerity. “Her singing is just so awesome. A lot of the blues things in my playing were coming more from singers like her and Beyonce than from guitar players.”

Despite Smith’s striving for a dense, constantly shifting sound, Rubin says he doesn’t find the album excessive at all. “I don’t feel like it’s challenging the way System of a Down is,” he says, citing another band he has produced. “Even when it’s complicated, it’s really digestible. And there’s a wildness to it, a certain live quality in the air that’s different. Things were kind of musically a little out of control. We realized it was going past the edges, but there was something exciting about that.”

Darkness has fallen in Anthony Kiedis’ Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills. We started speaking late in the afternoon, with Kiedis sipping tea while slung across a leather chair in a small library, but as the sun went down, he made no move to turn on any lights, and now I can hardly see him in the shadows. It’s unclear whether this is the result of his intense focus, some strange head game, or whether, if you’ve seen the things that Kiedis has seen, a small detail like interior lighting is hardly worth noticing.

Stadium Arcadium is the Chili Peppers’ first release since the publication of Kiedis’ best-selling memoir, Scar Tissue, in 2004. Alternately harrowing and hilarious, the book’s drug-consumption-per-page quotient is enough to humble Hunter S. Thompson and William S. Burroughs combined. The singer’s account of his lengthy battle with heroin addiction—alongside tales of his hard-partying father, actor Blackie Dammett, and turbulent affairs with actresses, models, and designers, including Ione Skye, Sofia Coppola, Yohanna Logan, and Jaime Rishar—ultimately resembles the lather-rinse-repeat instructions on a bottle of shampoo.

Kiedis, 43, claims that there was nothing cathartic about writing the book. “I had already processed the difficult things—the father stuff, the drug stuff, the self-loathing stuff, all of the psychologically intense and debilitating aspects of my life—before I did it in a more comprehensive body of work,” the singer says. “I don’t think I’d be of a mind to write a book if I hadn’t already dealt with all the major issues that were destroying me.”

Kiedis says people approach him every day to thank him for the book and tell him what they’ve taken from his experiences. Still, he expresses some misgivings. “I could have been a little bit more considerate,” he says. “I was trying to put everything on the table—and in my spirit of ‘Here it all is,’ I said things, particularly about girls I’ve had relationships with, that I regret.” Certainly, the farewells to some of his girlfriends (“I looked at Jaime one day and thought, ‘I’m not in love with her anymore’…It was as if a fog had lifted”) feel more intimate and uncomfortable than the lurid drug binges.

As for Kiedis’ longest-running partner in crime, Flea says that he hasn’t read Scar Tissue. “I think we have very different perspectives on our shared history,” the bassist says. “I picked it up and read one thing that kind of bummed me out, and I also read something that was really fuckin’ nice, too. But it was hard for me to read, and I didn’t want to go into rehearsal and feel that I might bug out.”

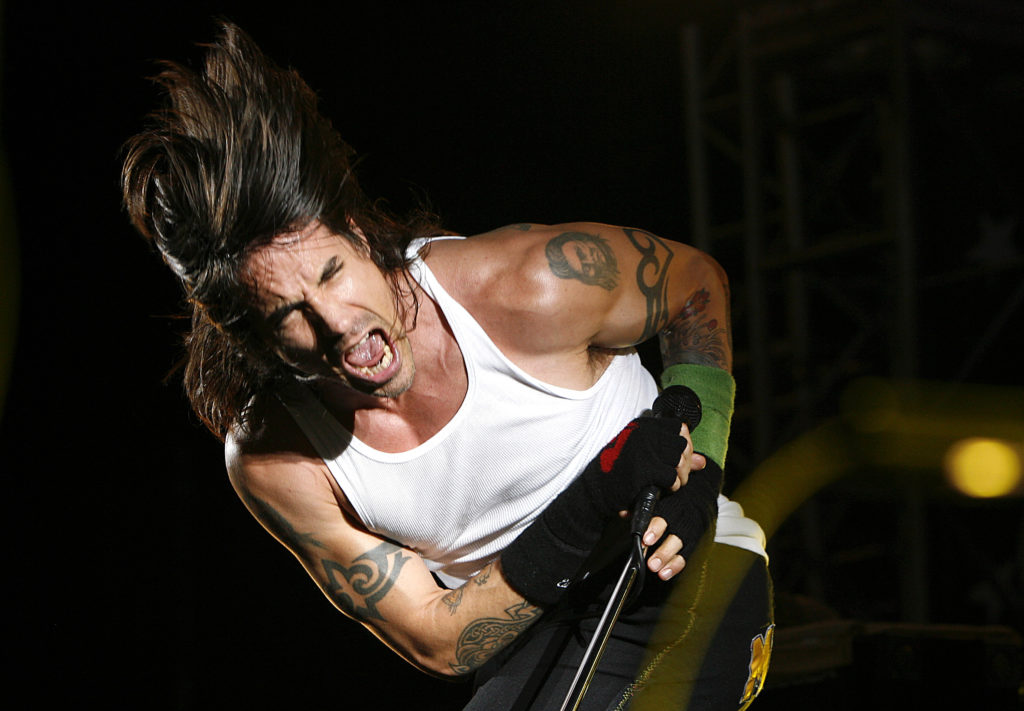

It may be true that the memoir didn’t lead to any personal revelation for Kiedis, but his continued growth as a songwriter and singer suggests otherwise. The lyrics on Stadium Arcadium are still hard to interpret literally—and sometimes rely too heavily on a kind of rhyming-geography game—but there’s an evocative sense of imagery that is sustained through a huge batch of songs. A notable strain of religious and biblical language (“God made this lady that stands before me,” “I’m consecrated, but I’m not devout”) runs through the album, which, he acknowledges, seems like a theme. But Kiedis says he hadn’t taken notice of it until someone recently pointed it out. And at some point in the recent past, he turned into a real vocalist—even on sweaty funk workouts such as “Charlie” and “Warlocks,” he sings where he previously would have just shouted and mugged.

“I’m so proud of Anthony,” says Flea, beaming. “When we first started this band, he couldn’t really sing a note. He would scream and holler and rap, and to see him coming up with all these great melodies and singing all this stuff—it’s probably, more than anything, the reason why we keep improving.”

“When you’re trying so hard to get the ears of the world, it’s really easy to be super-extroverted, to the point of obnoxiousness,” says Kiedis. “And it worked quite well, being the loud, brash, crass, aggressive guy. But instead of losing my voice or becoming a caricature, I found a way to make a transition into something new and different. And that would have been more difficult if I had been born a singer.

“I guess we’re all born with voices and the ability to dance around as kids,” he continues, “but I don’t think I came into this world with people saying, ‘Oh, this kid’s got a hell of a set of pipes on him.’ No one’s ever accused me of that my whole life.”

The Chili Peppers, Smith reminds us, “started as a joke band,” best known for songs like “Special Secret Song Inside (Party on Your Pussy)” and for donning socks on their dicks. “We did not have longevity written all over us,” says a deadpan Kiedis.

But somewhere along the way, the group turned into a rock institution. As they approach the quarter-century mark, they’re in rarefied company. Which bands can claim that kind of endurance while still making new music that anyone cares about? There’s U2, R.E.M., and MetallIca, and…well, who else?

Kiedis resists the comparison with those monolithic groups. “When I look at those bands, they seem like elders,” he says. “When I was, like, 20 years old, I was aware of all of those bands, and they seemed like they were in a different world than us.” The alt-rock luminaries he felt more kinship with—Nirvana, Jane’s Addiction, Smashing Pumpkins—were simply unable to keep it together for the long haul. Flea says that he feels a certain affinity for anyone who’s still out on the road after so many years. Still, he says, “it seems like those guys know what they’re doing, like they’re really smart, and it always seems to me like we’re kinda bumbling along.”

But Rick Rubin counters with a simple, and fairly unarguable, statement. “U2 and R.E.M. aren’t making better records now than they were when they broke,” he says. “The Chili Peppers feel like they just get better.”

And why shouldn’t they? It seems as though they’ve finally found the lives—and the sound—they’ve always wanted. Gatherings of the band now feel like family affairs, with significant others, babies, dogs. Frusciante recently bought a beach house to share with his girlfriend, Emily; Smith has his wife, Nancy, and Cole, and teaches drum clinics for young players; Flea continues to devote time to the public music school he helped found five years ago and is practicing his trumpet with new dedication. Only Kiedis—most recently linked to 20-year-old model Jessica Stam—remains not settled down, though the specter of drugs, so long his band’s true nemesis, seems buried for now.

“I’m feeling pretty good today,” says the six-years-clean Kiedis, “and unless you pull out a huge bag and put it on the table, I’ll probably be just fine. I have no interest in going back to the fear and confusion of my life during the last time I was using. I’m wearing life as a more loosely fitting garment, which fits me just fine.”

And as the band gears up for a lengthy tour—European dates in the spring, then the States starting in late summer, possibly with opener Kanye West—even the most reluctant Chili Pepper is fired up. “I’m definitely ready to get out there in the world,” says Frusciante with a smile. “I don’t have a problem with touring, because now we get along. Sometimes those guys feel like we’re not friends, and I’ve definitely gone through phases with Anthony and Flea where they think we’re not friends. But the narrow-mindedness that comes from me needing to occupy my brain all the time sometimes isolates me from the people around me.

“When we toured for By the Way and Californication, I kept my headphones on all the time,” continues Frusciante. “I think this time, I’m going to take the headphones off.”

Leave a comment