Blessed (and weird) are the record store saints, who save God-forsaken disks from ending up in landfill graveyards, finding them venerating homes, instead.

Unlike most independent record retailers following today’s standard playbook, replacing compact discs and used vinyl in their bins with virgin 12-inch vinyl re-issues and contemporary pressings, a few shopkeepers still operate shrines to holy relics of the 1950s to 1980s–original 45 rpm singles. No new ones are being pressed, so these halo-like plastic wafers inspire religious fervor and even madness

Consider Val Shively, who claims to stock over 4 million records in his overstuffed three-story shop, R&B Records. To a western suburb of Philadelphia trek collectors from the Far East and Europe. They come in search of mid-XXth Century icons, especially vocal harmony group sounds like those once recorded in Philly. Call them “doo-wops” or “moldy oldies”, these tunes bridged musical genres from jazz to guitar-driven rock, then rap. Some customers recall young loves or parents’ favorite songs, others are drawn by the sheer rarity of Val’s antiquities.

His store sells classic soul and country singles, too. Regardless of musical style, if it’s on 7-inch vinyl, he’s probably got it here. But first, newcomers may face Val’s devilish trolling.

His front door features a DO NOT ENTER traffic sign with “unless you know what you want” added in small print. The walk-in trade isn’t what it used to be (he’s been at this spot since 1990), but Val won’t tolerate timewasters. There’s just not enough room.

Squeezing through the entranceway tight with crates, shelves, black plastic in brown paper wrappers, publicity photos and framed record sleeves, you emerge into a cavern filled with floor-to-ceiling aging vinyl.

Val’s shop stocks CDs and even 12-inch platters, but overwhelmingly 45 rpm singles, acquired from failing wholesalers, jukebox suppliers, other collectors, as well as from shopping-bag-toting visitors. Though there’s no room for more, he keeps buying. Val admits: “It’s an obsession, it’s a sickness.”

Are there really over four million records crammed into this tight space?

“You want to count them?” Val’s voice and diction would fit into a movie starring The Three Stooges, who grew up not far from here. “I never counted them all.”

So he could have claimed just two million…

“I did, but nobody liked it. I asked people you like three, you like five? How about four million? Go ahead, do it. That’s how it happened.”

Don’t be fooled by Val’s fuzzy math. He remembers what he paid for almost every record in the place, often setting the price for a rarity that he’s bought and sold again. For disks that might have cost 79 cents at retail when first issued, prices range here from $30 to $4000.

Which of his high-priced relics would Val recommend to a deep-pocketed first-time pilgrim?

“I should pull out ‘Golden Teardrops’ by the Flamingos. Everybody likes that. It’s a classic. It’s over there in those boxes with the rare records.”

The 1953 release of “Golden Teardrops” on Chance Records, in red translucent plastic (“with slight label wear”) is priced by Val at $2500, about 15% higher than its weight in solid gold.

Listen to “Golden Teardrops”, with its smooth “ooh-ee-oohs” and “dum-dum-dum-dums.” Go back to when cool, mellow four- and five-part harmonies were the sound of young groups eager for their two-and-a-half minutes of fame.

Not a hit when first released, “Golden Teardrops” gained its reputation from word-of-mouth by a small group of avid collectors, prodded by a handful of dealers, including Val.

“This was the Flamingos with Solomon McElroy singing lead. Johnny Carter—he went on to the Dells—wrote the song and sang tenor…” Tumbling out of Val comes a verbal Wikipedia of vinyl lore. He can tell you about every group or recording he treasures in here, the other stuff not so much.

When a visitor asks about three scarce self-released singles by country and punk-ish performers, Val goes silent, briefly. “I don’t know where any of this shit is. Chuck! He knows everything in the place. I couldn’t run this business without him.”

Chuck Dabasian was hired by Val in his first shop when a regular visitor as a high-schooler. He’s worked for him full time since 1975 “After all these years with me, he’s still amazing–very pleasant and patient. When he works with customers, nobody wants me. They all want the nice guy!”

Chuck and his employer are stumped by the first request, Willie Nelson’s “No Place For Me”–self-released on the Willie Nelson Records label in 1957. Val vents: “That was Willie Nelson’s first single? Never heard of it. I don’t know that much about Willie Nelson. When I see him, I want to give him a cake of soap. But he wrote one of the best records ever: ‘Crazy’!”

The next single sought is the punk band collectible, “Hey Joe” by The Patti Smith Group, pressed on the band’s own Mer label in 1974. “We don’t have it, I know,” says Val. This comes as a disappointment since the featured guitar player on the song is Lenny Kaye, legendary rock critic and former oldies record store manager and 45 collectors’ influencer.

Last on the wish list, a 1981 off-beat hit by multimedia artist Laurie Anderson, “O Superman” turns out to be on a shelf two feet away from Val’s swivel chair. “Who is she? How did you find it, Chuck? Where did we get this? Did you buy it? If you did, you’re fired!”

On one matter, there’s no argument between the two vinyl addicts. “The worst song ever? ‘Paralyzed’ by The Legendary Stardust Cowboy.” Chuck reaches for it, but Val stops him. “It’s just some guy yelling over a guitar.” Yet the 1968 release has its fans, like David Bowie. Has anyone like Bowie come in search of such treasured recordings?

“Nah, Bowie’s never been in here. Most people who come in I don’t know who they are. The other day these guys say we’re with Jazzy Jeff, can you close the store down? I said I don’t have to–nobody comes in anyway. Let me ask you a question, which one is Jazzy?”

Val doesn’t recognize anyone from TV, let alone local rap legends like the Fresh Prince’s DJ, unless there’s a connection to the Golden Age of 45s.

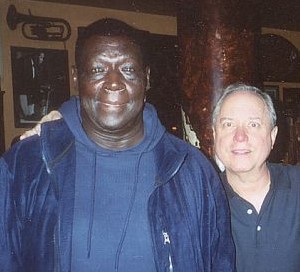

That’s why he’s aware of one celebrity visitor–musician / historian / griot and drummer for The Roots and TV’s “The Jimmy Fallon Show” band. “Questlove comes in here. A lot of people don’t know his dad was Lee Andrews.” For those not familiar with the name, Lee Andrews & the Hearts were one of the classic Philadelphia doo-wop groups of the 1950s.

Both father and son are pictured posing with Val among the hundreds of photos posted on the R & B Records site.

Online the shop is even more crammed with vintage memorabilia than the real world store. Click on a link to Val’s PHOTO GALLERY and you get a choice of 10 different galleries full of old publicity photos of groups and singers, Val with doo-wop vets at parties and in the store, his life in vinyl commerce, as well as one gallery devoted to Val’s wife of 32 years, Patty (the only woman who could handle him for so long, she started a Wives Against Collecting group at one point to keep his vinyl mania in line).

Without visiting Upper Darby, PA, visitors can experience Val’s unique presence throughout his Web home. Videos of the shop are as close as SEE THE STORE IN ACTION or VAL’S VIDEO PAGE links. A click on HISTORY leads to an 11,000-word memoir in type, about collecting old 45s, opening his store, pursuing his dreams, losing his way until he was reborn, baptized by the church that now occupies the store next to his. He writes in his online testimony: “I try to put the Lord first, read the Bible, tithe, and start and end each day in prayer.

It’s hard to reconcile Val the pious with his doppelganger, the trolling vinyl imp. At the bottom of the door to his virtual store, instead of a “Do Not Enter” traffic sign, there’s another customer-hostile deterrent–an offering with each disk purchase of free insects.

In his shop at age 77, Val keeps bringing up the imminent death of his business. “When I started out—most of my customers were in high school or college. Now they’re making funeral arrangements. They’re all dying. It’s all over. Nobody’s buying these records. Who comes in here anymore?”

He does get new walk-in customers, different from the aging fanatic collectors (mostly male and nerdy) of harmony groups who made his business successful. “Now we get women who are D.J.’s who play soul and dance music. They like playing old 45s and they’re young and they look nice.” But there won’t be enough reinforcements to keep his store going as older buyers disappear.

At home, Val’s private collection of 11,000 singles has attracted the interest of the Library of Congress, which could buy the lot to preserve in its recorded sound collection. The four million slabs of vinyl surrounding him in his store face an uncertain future. There are just too many for any of the dozen public or educational institutions with popular culture collections to acquire.

“So these records end up in landfill,” Val shrugs. “People 5,000 years from now could dig them out and figure out how to play them and hear what we listened to. They may like it as much as we did.”

Leave a comment