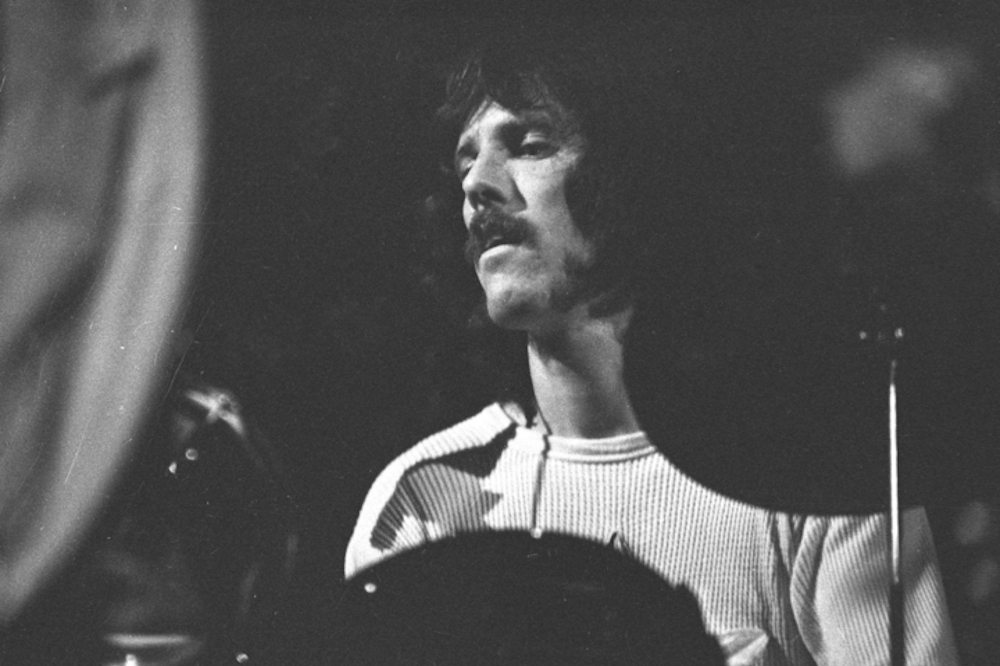

In his post-Doors life, drummer John Densmore is as much, if not more, of a writer than a musician. The author of two best-selling books, Riders On The Storm and The Doors Unhinged, he began working on his newest collection, The Seekers: Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (And Other Artists), several years ago.

Inspired by the George Gurdjieff book Meetings With Remarkable Men, Densmore’s newest work, out on Nov. 17, focuses on the mentors and musicians he says “fed him” over the years. Each chapter highlights a different musical icon, weaving tales of his relationships with bandmates Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, alongside Bob Marley, Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Paul Simon, Janis Joplin and many more.

The collection is a joyful history lesson for music geeks: Densmore is equally candid, like in discussing an unfortunate experience with Van Morrison, and conversational, documenting hangouts with Willie Nelson.

SPIN spoke with Densmore about the book, reexamining his relationship with the other Doors members and being there countless times for musical history.

SPIN: I like that you start with your mom, then music teachers. Did you write these chronologically or put them in order after the fact, like sequencing a record?

John Densmore: I wrote them individually and then put them in order. I thought, “Oh, I’m gonna start with my mom because she supported my drumming and my piano playing and encouraged me. So that’s a good place to start.” Then I think it’s in the Elvin Joes chapter that I start talking about drummers and everyone else — the first drum beat we ever hear is in the womb, our mother’s heartbeat. And then I thought, “Well, of course you started with your mom because you came from her womb [Laughs].”

Do you see a unifying theme in the artists you chose?

I wrote a few chapters on some of these icons who fed me. Then I started to think, “OK, let’s try to make this chronological.” And then I started piecing that together. I was struggling with what unifies all these people. And I got to the love of sound — like painters see the world, musicians hear it. That’s why they’re all connected. If you watch Bob Marley and you watch Gustavo Dudamel, the L.A. [Philharmonic] conductor, they’re connected — what you’re seeing is their entire body emanating the sound ‘cause they’re so gone and so into it.

How did you decide on the artists you included?

My intuition told me the big ones, the ones that influenced me the most. Elvin Jones was my idol, and he still feeds me, so he’s gotta be in there obviously. And then Ravi Shankar was very important to me, and I studied with him, so he has to be in there. Then a little later I’m thinking, “Wait a minute, Jerry Lee Lewis.” We were really proud to help jumpstart [a comeback] – looking back at the ’50s rockers, nobody did that before. Well, the Stones got B.B. King on tour — that was very cool. And very early, they got Howlin’ Wolf on a TV show or something. But as you read, we tried to get Johnny Cash and they said he was a felon. “OK, you just wait a year or so. He’s gonna be a giant American icon, you jerks.” I like helping the music lovers understand we’re all on the shoulders of previous generations of music-makers.

It was also interesting you chose to include the Van Morrison chapter after having the negative experience at the Hollywood Bowl.

I still, as I said, hear “Into The Mystic” and go, “Oh my god.” Those in the biz know his personality. I said what I had to say because I was annoyed and I also admire his talent. Jim could be an asshole — that’s for sure.

And you address that in the Paul Simon chapter, where you talk about Paul remembering Jim being rude to him at the Forest Hills show.

It was 50 years later, and I could not believe that Paul remembered it. It stuck with him because he was trying to help a young band, encourage us to do well, opening for them. And to see the lead singer, after being kind of dismissed by him, become this giant icon, I’m sure he was scratching his head for those 50 years, going, “Wow, what is that?” And it felt kind of healing to discuss it. It was kind of insightful, the two of us figuring out that maybe [Morrison] was nervous — like Trump, who gets defensive when he’s nervous and doubles down on being an asshole.

Did writing about these relationships, like Jim and Ray, give you a new perspective?

Oh, man, I miss Ray, musically more than ever. It really hit me how, god, he’s a bass player and a musician who plays lines that get etched on our foreheads forever ‘cause they’re so melodic and catchy, [like] the Bach “Circle Of Fifths” intro in “Light My Fire.” Ray even said, “We admire Herbie Hancock, but we’re not as proficient as these guys.” But they feed us because we admire them. But Ray’s unique lines that he wrote — that’s the gift. Obviously there would be no Doors without Ray.

I like how you interweave personal anecdotes too, like making up with Ray.

Well, the perspective is kind of like what I saw last night when I YouTubed the Beatles’ acceptance speech for the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. George [Harrison] was saying, “I wish John [Lennon] was here. I know he would be here, and we love John.” They had their struggles, John and George, not as heavy as me having a lawsuit against Ray and Robby [Krieger]. But if you’re one of the Fab Four, or one of the fab Doors, then you’ve gone through this hurricane, and only those four have lived it and really feel the camaraderie that no one else can. Even with all the trials and tribulations, wow, there’s a deep, deep bond. I’ve been married three times, and I am going to get married again, but, gosh, my relationship with the Doors is obviously the longest of my entire life, and the deepest. I did Charlie Rose for my last book, and I remember a quote that was pretty good that he loved. I said being in a rock band is polygamy without the sex. So you’re married.

Is it hard for you revisiting your relationship with Jim again after so many years?

If it’s all guys, a band is definitely a band of brothers. It’s your brother. It’s sibling rivalry, so when Jim first passed, I was sad, but it took me a few years to deeply mourn ‘cause I was mad at him. I couldn’t accept that creativity and self-destruction came in the same package with him. It doesn’t necessarily have to with an artist. And now, I’ll still hear some obscure line — last night I was thinking of “Land Ho!” because something of the navy and I thought of Jim and his dad. And I’m still picking up stuff, and the love is deeper. I get a little metaphysical in this book and say I’m having a lot of conversations with Ray and Jim now. Well, why not? I love that [George] Harrison line about how he has a deep relationship with John — and if you can’t have that then how are you going to have it with Jesus or whoever you think you’re gonna see in Heaven?

You mention art and self-destruction, but then you talk in here to guys like Willie Nelson and Paul Simon who are still thriving in their 70s and 80s. How does it inspire you?

Yeah, Paul Simon and Willie Nelson are mentors for me in the area of aging because Jim went at 27 and I’m 76 in a month. There’s Jim’s road, and there’s my road, which is less self-destructive as an example for young people, which I like. But I also get fed by how Willie and Paul are doing it. They’re still incredibly creative and vibrant. They’re not in a rest home. That’s a real turn-on, and maybe that’s the key to their longevity and vibrancy: being engaged.

One of the cool things I think to come out of the book is there is no right path. You mention that you were surprised when Patti Smith moved to the midwest but then found it heroic. And now she is more vibrant and relevant than ever.

What a mentor for me as a writer. My god, it’s one thing that she made this incredible contribution to really jumpstart the entire punk movement. Then she gets the National Book Award for writing [Just Kids] — what the fuck? Whoa. So maybe she’s channeling that energy, whatever it is that makes her do music or write. Or the energy that comes through Willie or Paul Simon, she’s just channeling it. And she can almost do anything if you tap it without ego.

When you first saw Bob Marley, did you know that he was that special right away?

Yeah, I was really blessed on that one. When I saw them second-billed to Cheech & Chong at the Roxy — oh, my god. It was culture shock. I just knew, “This is coming.” Me and Robby were in Jamaica before. I’ve been so blessed to be on the front end of all this stuff, like reggae and Marley. I meet Gustavo Dudamel when he’s guest conducting and know something’s coming. I meet Jim and know he’s gifted at something. You see Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary? I’m in there, and I have this sense: I’m a teenager, and I don’t know that Coltrane is going to be a giant icon, but I know there’s something here. I stumbled into the incubation period of all these things, Coltrane and reggae and classical music at the L.A. Phil. I’m so lucky to be sensing the incubation period of all these different powerful musical movements.

Is it luck or being open to them, though?

Open and interested — and maybe this sounds a little [egotistical] but [having] an intuitive sense. I trust my intuition, and I’ve got a pretty good intuitive sense to sniff out creative movements.

But you are also honest about the opposite, like admitting you didn’t get Lou Reed at first.

Yeah, right — even Patti I didn’t quite get at first. There are many roads to Jerusalem’s wall. That’s out of a poem.

Was this book easier to do because of the subject matter?

Oh, that’s a really good, good way to finish this up. The first two books I wrote were written in blood. This one was written in love. A loving tip of the hat.

Leave a comment